Montpellier—the French city located on the southern coast by the Mediterranean sea and the fastest growing city in the country—receives France’s second largest budget for culture, of course, after Paris as art city-in-chief. The sun shines three hundred days of the year and, so Montpellier’s mayor Philippe Saurel tells me, the city is not a hive of industry, it is instead best known for its art, sports and leisure. Those visiting the city on holiday or, indeed, discovering it through the digital tourism site that is google.images, will most likely recognise it for its old town, with cobbled streets and yellowy cream buildings which are all required have the same blue-grey painted shutters, window frames and doors.

This uniformity ends with an unexpected and enjoyable suddenness, on entering the labyrinthical Musée Fabre. The museum is made up of three different buildings, which immediately removes the element of clean symmetry and architectural consistency that frames typical museum buildings. From a darkened, modern entrance hall which feels almost business-like (complete with some of the shiniest floors I’ve ever slipped down, mirrored throughout the city in some highly buffed cobbled streets. Drunks, beware!) a disjointed warren of stairwells, levels and rooms open up varying drastically in wall colour and decor, though offering a coherent journey through a sizeable chunk of art history and the modern era—including the Dutch Masters and 17th century French and Italian painters right through to Marc Devade, Louis Cane and Vincent Bioulès.

Alfred Bruyas, a collector who provided many works to the museum, weaves his way hilariously through numerous pieces in the collection, presumably buying slots in some, his vibrant red hair and beard immediately recognisable, whether greeting his personal friend, Gustave Courbet on a grass-lined path in the artist’s The Meeting (“Bonjour, Monsieur Courbet!”) or looking serious and rather deeply into the viewer’s eyes in Alexandre Cabanel’s Portrait d’Alfred Bruyas.

French contemporary artist Sophie Calle pops up in an equally surprising manner amongst various eras of painting and sculpture, with her series Blind People, in which she asks visually impaired participants what their idea of beauty is and then presents an image to illustrate the answer. The works are presented as part of a long-running exhibition at the museum that ends this May: Art and Material–A Gallery of sculptures for touching. The exhibition invites visitors to physically touch a selection of ten sculptures from the museum itself and well as the Louvre.

Not physically interactive, but nonetheless pulling the veil back on the typical formality that surrounds works in museums, there is also an experiment in play in one room: a painting undergoing a treatment which registers movement and the causes of cracking for a six-month period, with technology that doesn’t look too unlike telemetry leads.

After much weaving between long corridors, vast rooms, rows of hall-of-mirror-like doorways and staircases up and down, visitors are presented with yet another surprise: the permanent and specially-built space that houses numerous works by Pierre Soulages—born in nearby Rodez, where a large collection of the artist’s works can also be found. In contrast to the majority of the building, the space is clean and modern, with vast white and concrete walls and luminous panels which stretch floor-to-ceiling, wall-to-wall across one entire length. His works from the 70s to the 00s sit upstairs, the light shining off a series of black painted works which examine the nature of this apparent non-colour (always a rich colour for Soulages), drawing on the texture and depth made possible in its application, at times appearing almost silver.

I also visited the city’s Carré Sainte–Anne, a renovated, desacralized neo-Gothic church which now hosts a contemporary art gallery, where German artist Jonathan Meese has made a literal mess (badum tish), with a large-scale installation intended to reflect his studio life and inner workings which includes, amongst many other items, multiple cutouts of Scarlett Johansson glossy ads, swathes of fabric, original paintings, TVs, metallic paper, Moomin figures and giant silver balloons. The artist, who was famously taken to court after giving a Nazi salute in a performance, has been given total freedom here to create what he likes—as every artist invited to show at Carré Sainte–Anne is advised to do. As the gallery’s artistic director, Numa Hambursin, tells me, it’s been a controversial choice for a public space. I’m not a fan of the statement artist, but this kind of exhibition does draw things away from the typical treatment ex-churches receive, with pretty pictures hung around traditional brick walls. Since Hambursin’s placement, the gallery has attracted artists including Marc Desgrandchamps, Robert Combas and Octavio Ocampo.

Far more exciting, however, is the current reworking of the city’s La Panacée, which has recently been taken into the charge of Nicolas Bourriaud. La Panacée exists as one of three strands of the eventual Art Center of Montpellier Méditerranée Métropole which also includes an art school–The ESBAMA–and the future MOCO.

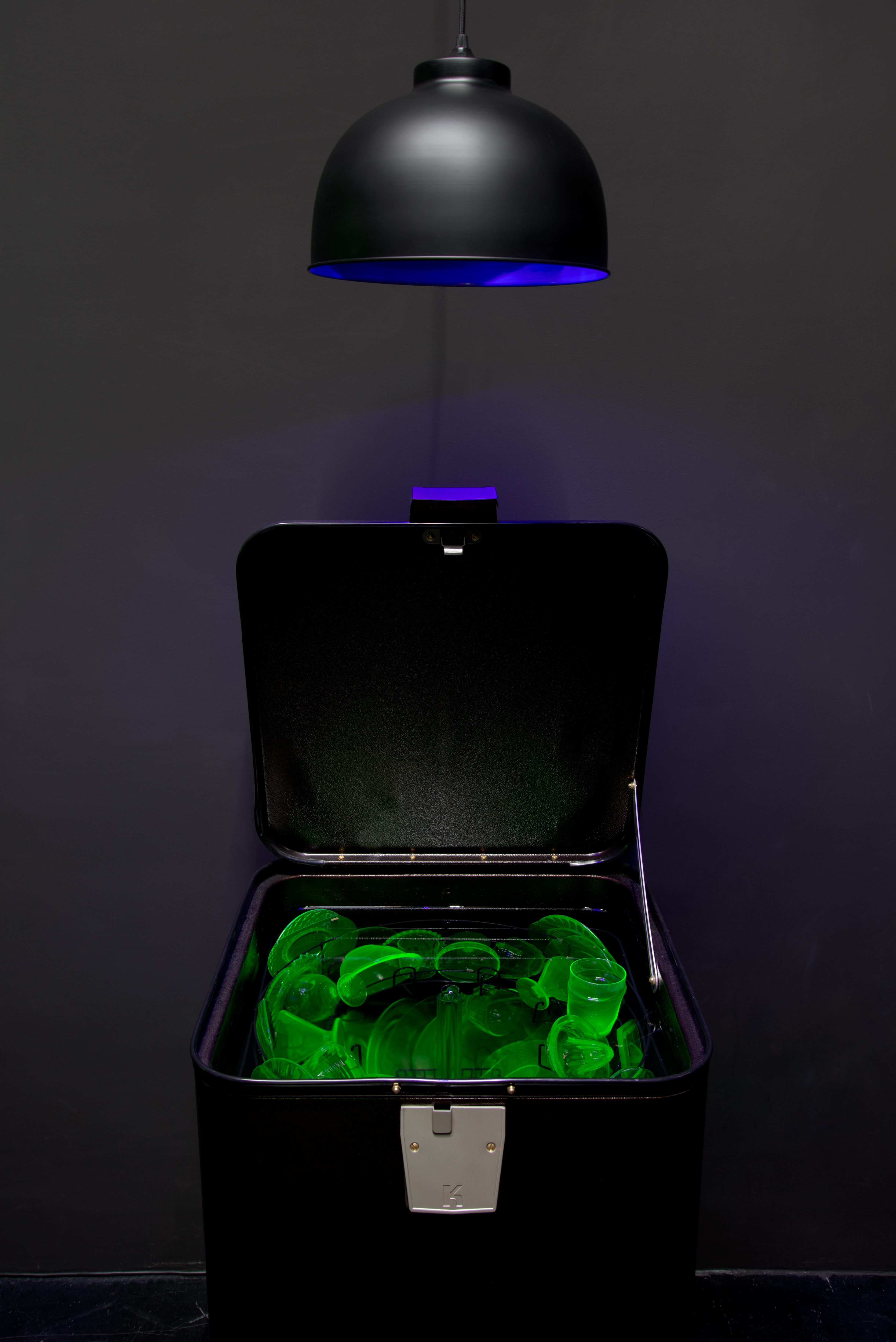

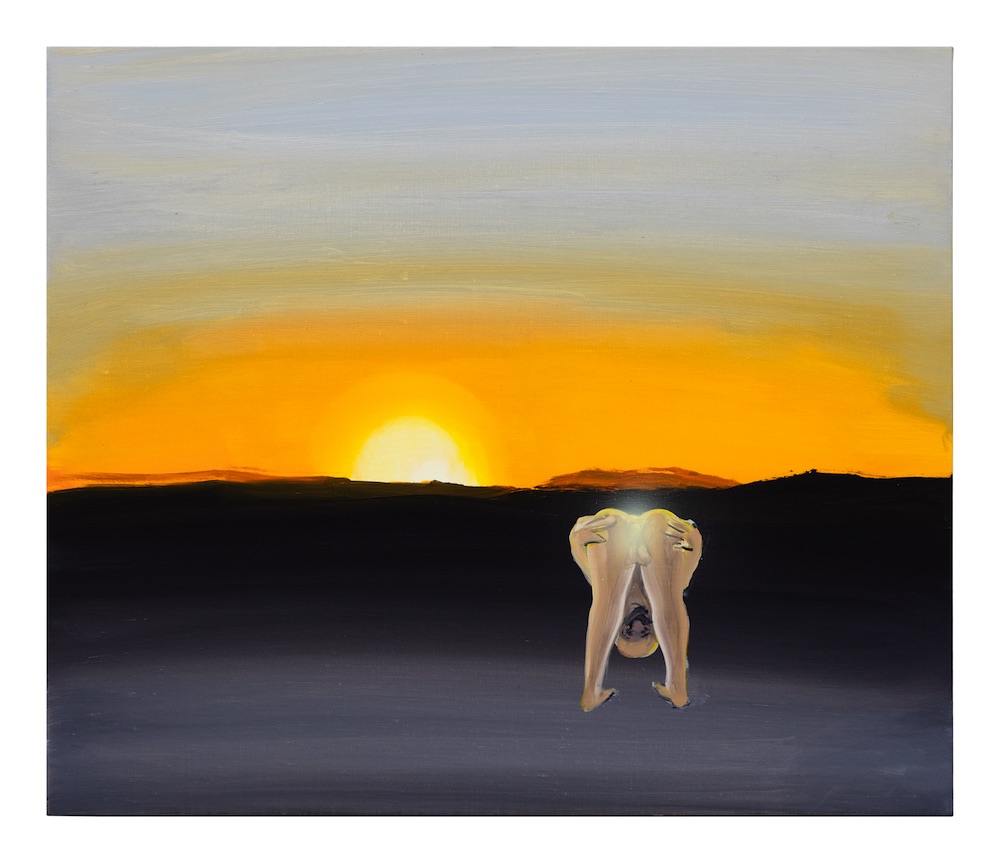

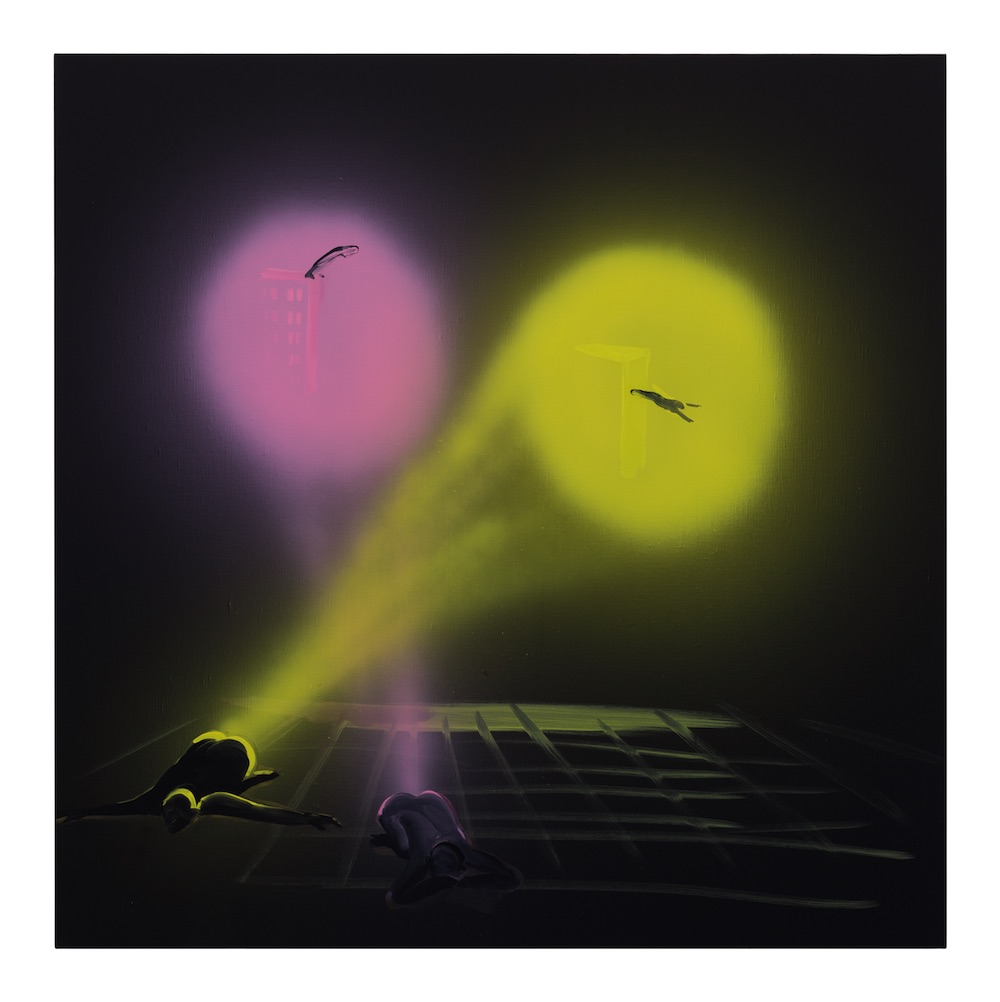

La Panacée itself, a light-filled, square space which has rooms surrounding a central courtyard, operates with three consecutive exhibitions; currently a solo show from the brilliant Tala Madani (whose works swing between funny and twisted, depending on quite where your sensibilities lie), a group show which focuses on labour and another group show, Return to Mulholland Drive, which takes its cue from David Lynch’s 2001 film of the same name and carries the most signs of Bourriaud’s creative curation within the gallery. For all three shows, the surrounding text is minimal and the works—plus their placement together—largely speak for themselves. In Return to Mulholland Drive, artists’ names and work titles cannot be found on the surrounding walls, the works instead (coming from artists such as Ugo Rondinone, Torbjørn Rødland and Joyce Pensato) form a wider, complete body throughout the space with which to explore this film and a pivotal moment in the middle, which involves a blue box. Much like the movie, clues are laid down but not spelt out.

“It’s important for an art centre to press the pause button,”

La Panacée used to be a centre for digital art, and while there is not a sense of turning back the clock here, there is a concerted effort to slow it down. “It’s important for an art centre to press the pause button,” says Bourriaud, noting the need to move away from a single focus: “The time we’re living in is not good for that.”

The space which will perhaps best display the curator’s interests is the yet-to-open MOCO, which will be housed in an ex-military residence and open in 2019. It’s planned to be a social space, with plenty of room for interacting with fellow visitors on the ground floor. It will be a museum which shows only the collections of others—artists, private collectors, galleries and institutions—with each show drawn from a single collection. It will include a research centre about collections and ideally, in the words of Bourriaud, set up Montpellier as a “hub for collectors.” At this point, La Panacée will become much more focussed as a space for emerging artists.

MOCO is situated in front of a garden, with a tree-lined path and two enormous trees standing sentry by the gate. From the outside, it carries all the characteristics of a Montpellier historic centre building, but it will be worked on extensively on the inside by the curator and architects who will be announced on 6 April. Away from the frenetic activity of larger cities, this does feel like the place for a more considered art space which could allow not a whistle-stop tour but a platform for conversation and contemplation. There’s a slowing of pace. As Bourriaud reminds us, “it’s the only left-wing city remaining in France.”

It was only on the last day of visiting Montpellier that I ventured outside of the historic centre, where the uniformity stops and the comfortable old-world bubble bursts. Part of the town hall, designed by Jean Nouvel, could have sprung from a Ridley Scott set, with enormous deep blue and silvery panelled structures reflecting the sun and stadium-like roof panels hovering over a central atrium. It looks as though it could take off into the sky at any moment. Along the river, from both sides of the town hall, new buildings have sprung up at speed, including Philippe Starck’s 2014 building The cloud which houses a wellness centre, multimedia library and Olympic-sized swimming pool. The buildings appear to revel in the freedom allowed in this part of town, away from the protection and rules which surround the traditional buildings in the historic centre. A number of trams, one of the only elements of the city to traverse between the old and new towns, have been designed by Christian Lacroix. It’s clear to see that a lot of money is being spent.

Coming from London, I’m often suspicious of the “new”, as it tends to find itself replacing the old, or squashed up amongst it, a threat to the more aged buildings and institutions rather than something which develops harmoniously alongside them. The lack of integration between the new and old areas here however, while appearing clunky or disconnected in places, offers potential for every part of the city to carry on in its own way, in a manner that doesn’t merely decimate the past. I leave with a sense of real excitement for the developments that will have transpired by my next visit–not least MOCO–but also, with absolute certainty that little will be lost.

La Panacée’s current programme is showing until 23 April lapanacee.org / ‘FRANÇOIS ROUAN Tressages 1966 – 2016’ shows at Musée Fabre until 30 April museefabre.montpellier3m.fr / Joanthan Messe is showing at Carré Saint Anne until 30 April