We Earth-dwellers have an innate connection with the moon. It’s forged from infancy, through nursery rhymes and picture books, where the moon is usually drawn as a jolly visage, in full portrait or crescent profile. We grow conscious of how it shapes our world: its gravitational effect on the oceans’ tides; the lunar calendar that might denote fast days or feast days; the notion that its phases affect our psychology. It orbits Earth at an average distance of 384,000km: we look at it directly, and dream of it endlessly through art and music. This year, the fiftieth anniversary of the moon landings—when US astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin made one small step/one giant leap on July 20, 1969, broadcast across Earth’s networks—has also reflected its impact on decades of creative expression.

I find myself rocketing giddily into space; the Earth slips away from my feet, and brilliant lights whoosh all around me. I can’t look away, so I close my eyes for a minute, worried that I’m going to throw up. When I regain composure, I am bounding along a weirdly familiar, dusty surface; I hold out my arms, which seem to stretch like spaghetti, and wave at my shadow. I start to float and explore; constellations, DNA codes and debris rush past me at points. When a small rock smashes into my visor, I panic.

“The moon lends itself to immersive, exploratory art expressions”

I am actually perched on one of several chairs in the tiny studio space of Manchester’s Royal Exchange Theatre, and this is To the moon: a beautifully trippy VR installation created by Laurie Anderson and Hsin-Chien Huang, and premiered during Manchester International Festival in July. It is a meditative, surprisingly humbling expedition, set to an elegantly mournful soundtrack, and reflecting not so much on an alien planet, but our own global human behaviour, intrepid nature, territorialism and destruction. At one point, Anderson’s narrative explains: “You know the reason I really love the stars? It’s because we cannot hurt them… But we are reaching for them. We are reaching for them.”

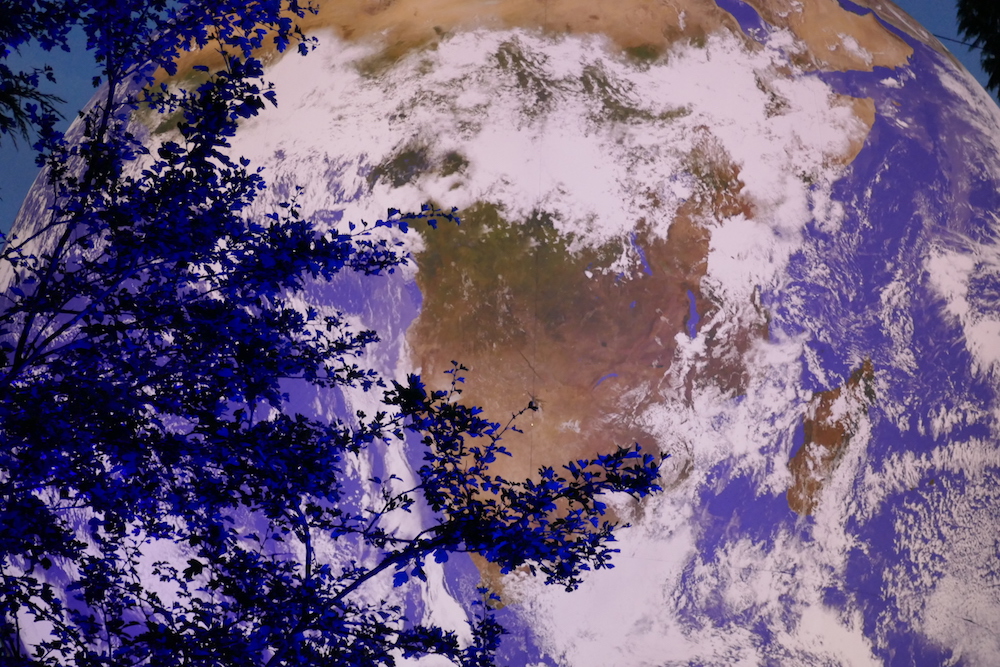

The moon lends itself to immersive, exploratory art expressions. That’s also evident in the multi-disciplinary work of Bristol-based artist Luke Jerram; his fantastically ethereal installation Museum of the Moon has toured extensively since 2016: an intricately textured seven-metre-diameter balloon-planet that is a 1:500,000 scale reproduction of the moon created from NASA data, looming over locations from major museums to Glastonbury Festival, and even a swimming pool in Milan. Throughout this summer and early autumn, the Museum of the Moon’s sister work, Gaia, involves several Earth sculptures (illuminated internally, and 1.8 million times smaller than the real thing) appearing simultaneously at venues including Peterborough Cathedral (which forms an aptly spiritual setting), Wales Millennium Centre, the National Science and Media Museum in Bradford, and September’s White Night festival in Riga

, Latvia. By standing 211 metres away from Gaia, we are able to view Earth as it appears from the moon.

- Left: Luke Jerram and Museum of the Moon; Right: Museum of the Moon by Luke Jerram. Les Tombees de la nuit, Rennes, 2017

Jerram recalls his own childhood yearning to explore the moon, and his adult perspectives as an artist: “From the beginning of human history, the moon has acted as a ‘cultural mirror’ to our beliefs, understanding and ways of seeing,” he says. “The ethereal blue light cast by a full moon, the delicate crescent following the setting sun, or the mysterious dark side of the moon has evoked passion and exploration.” He also points out that it was only in 1968, through NASA’s Earthrise photo, that humanity could fully regard our own planet for the first time (“as a blue marble of life, floating in blackness of space”).

In many ways, 1969’s Apollo 11 mission was an art spectacle—not merely in the sense of conspiracy theories, but the way that the moon landing united science and mass media experience. An estimated 600 million worldwide viewers watched the event broadcast; my dad recalls listening to it on a handheld radio as a young man, as he walked through Baghdad’s streets. It has been entrenched in pop culture ever since—although it’s also worth remembering that even arguably the first movie blockbuster, La Voyage dans la Lune (dir Georges Melies, 1902) was shooting for the moon decades earlier.

Another legendary movie tagline may insist that “In space, no one can hear you scream”, but the moon has also always been inextricably linked with multi-genre music, from classical and folk to prog rock and electronic melodies. The greatest moon music feels timeless and weightless—take Brian Eno’s sublime ambient work Apollo: Atmospheres and Soundtracks, originally released in 1983, and still brilliantly toured as a live multimedia concert by British collective Icebreaker. David Bowie released Space Oddity in 1969, a few days before the Apollo 11 mission launched; apparently, the dreamy track was used to soundtrack television coverage at the time, despite its bleak denouement (where mythical astronaut Major Tom is stranded in space). “I’m sure they weren’t listening to the lyrics at all,” an amused Bowie would later observe. “It wasn’t a pleasant thing to juxtapose against a moon landing. Of course, I was overjoyed that they did.”

Historic orchestral concert series the BBC Proms, held annually at London’s Royal Albert Hall, has this year devoted an entire section of its programme to moon-related sounds, ranging from the world premiere of Canadian composer/pianist Zosha Di Castri’s Long Is the Journey, Short Is the Memory, to the enchanting CBeebies kids’ Prom: A Classical Trip to the Moon, sample-fuelled duo Public Service Broadcasting recreating their 2016 album The Race for Space, and a late-night show of sci-fi film soundtracks (including Clint Mansell’s wonderfully eerie score for moon, directed by Bowie’s son Duncan Jones in 2009).

“From the beginning of human history, the moon has acted as a ‘cultural mirror’ to our beliefs”

“The moon landings theme spans so many different audiences, and it still attracts us because space feels intangible and unknown; music sheds light on that in an exciting way,” says Proms director David Pickard. “We looked at the diversity of the music in the year of the moon landings itself, and we also had contemporary premieres including Hans Zimmer’s Earth, which really zooms in on our world from space.”

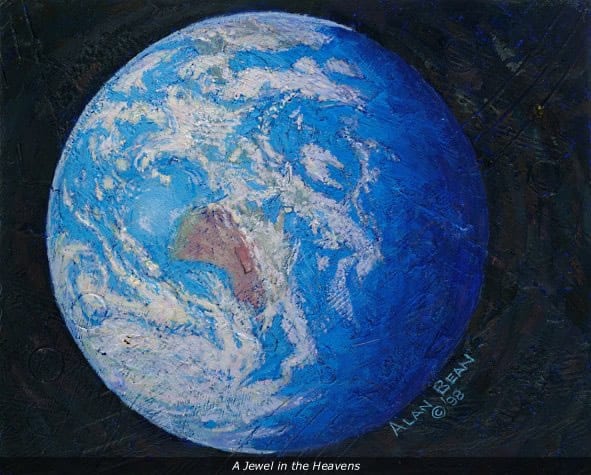

The moon landings evoke a wealth of mysterious mementoes, whether it’s the artefacts displayed at current exhibition The Moon at the National Maritime Museum in London (spanning psychedelic lunar photography to a tablet from ancient Mesopotamia), or the moon dust and spacecraft debris used in the paintings of US astronaut turned artist Alan Bean (technically, the fourth man to land on the moon, as part of the Apollo 12 mission in November 1969). Bean died last year; his otherworldly media formed the most fascinating aspect of his designs, but there is no denying his unique perspective.

Elsewhere, there are enigmatic, abstract projects such as the late-sixties Moon Museum (a tiny ceramic wafer containing works from artists including Warhol and Claes Oldenburg, possibly left on the moon by Apollo 12). In the twenty-first century, there is also MOCAM: the Museum of Contemporary Art on the Moon conceived by Julio Orta in 2016, and apparently located within “the extreme NW corner of the recognized lunar chart”. There have been a dozen men on the moon to date, and NASA recently announced plans to put the first woman (and the next man) on the moon by 2024. When I land back from my solo lunar trip in Manchester, with Laurie Anderson’s reassuring “Welcome back” in my headset, I have trekked across the moon on a donkey, almost fallen into an abyss, viewed Earth from afar, and floated beyond the atmosphere. It feels like there is so much heart-breaking beauty out there, and so much further to go.