Look a little closer at the vibrant, bold shapes and patterns in children’s playgrounds around the world, and you may begin to see some uncanny similarities with modern and contemporary art. This connection certainly rang true for Nazif Lopulissa

, who created a series of works inspired by some of the close-up patterns, smooth forms and careful engineering of these public spaces, which trigger an intrinsic sense of play in adults and children alike.

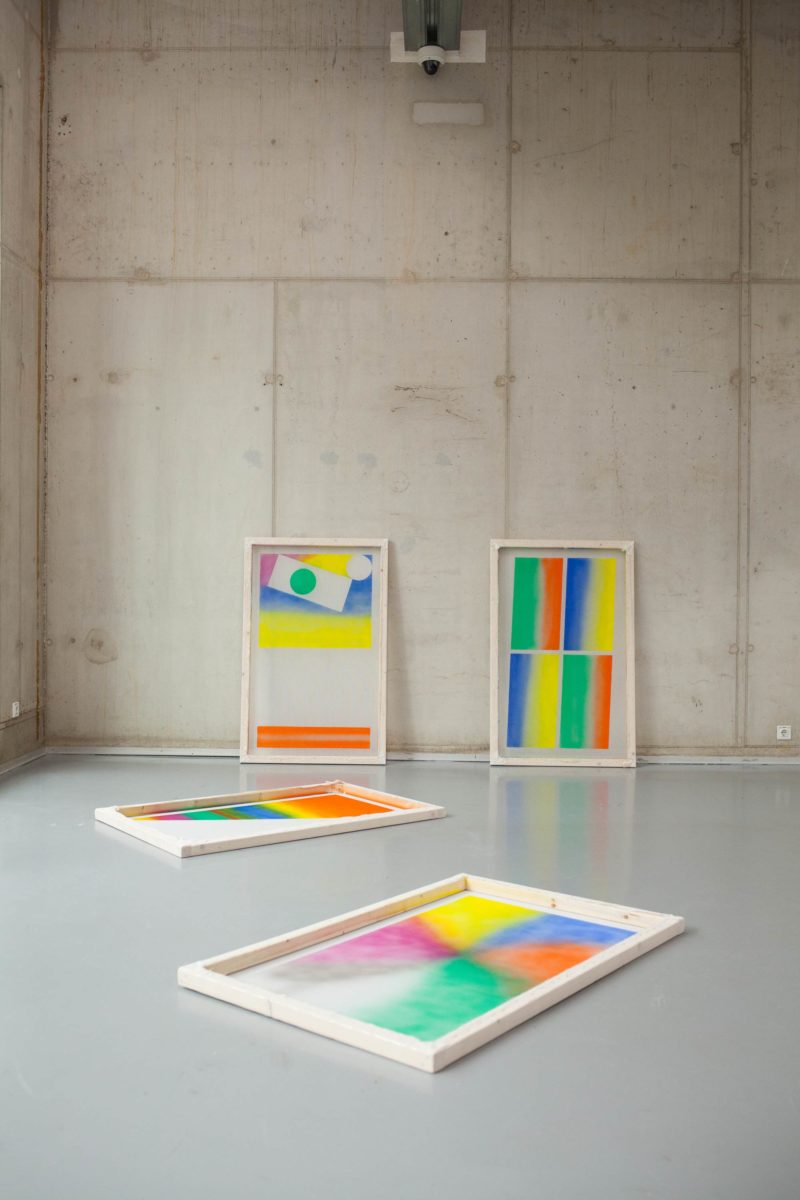

The young Dutch artist graduated from the Willem de Kooning Academy in 2016, and won the Henri Winkelman Award 2018. His exhibition Playgrounds showed at the Kunsthal Rotterdam last year, as part of Kunsthal Light, and it was supported by Winsor & Newton and The Fine Art Collective, who have been championing his practice since art school. We spoke with Lopulissa to find out more.

- All images: Kunsthal Light #18, Nazif Lopulissa. Photography by Marco De Swart, unless stated

Can you tell me a little about your 2018 exhibition at Kunsthal Rotterdam?

My exhibition Playgrounds was presented under the umbrella of Kunsthal Light, an ongoing programme that allows young artists to present themselves to the audience of De Kunsthal. It is always in the same space, which allows people to discover the work both from outside the building and up close when inside.

The series of works I presented in Playgrounds, I specifically chose to paint by hand. They investigate forms, shapes and structures from children’s playgrounds as a space of contestation. While making the new works I found that working directly on the canvas gave me the freedom to also work with these shapes in a physical way, and to approach the canvas really as a playground by itself.

What is it about the playground that interests you—and why do you see it as being full of contradictions?

I have very fond memories of the playground from when I was a kid. I thought a lot about playgrounds, because they are essentially collections of happy, colourful shapes and materials that are free to interpretation by the child’s mind; something to trigger them to enact their fantasies with. At the same time, however, playgrounds are very carefully engineered. Everything has to fit within exact standards, regarding budgets, but mainly safety as well. Which is really the opposite of what they are supposed to look like in the first place.

“That relationship between fantasy and reality, thinking of something and then making it real through making art goes a long way for me”

- Round and Round, 2017

Do you feel a connection with your childhood through your explorations of the playground, or was it something you wanted to approach more formally?

I think both. My childhood plays an important role in my work. For example, as a kid I always wanted a turtle, but my mother wouldn’t let me. She told that if I could draw a turtle, I could have as many as I wanted. That relationship between fantasy and reality, thinking of something and then making it real through making art goes a long way for me. At the same time, the playground is such a fascinating space because it brings these two ideas together: childhood fantasy and freedom, and safety and control. These are also the opposites that determine my practice, starting with recognizable shapes of the playground and then figuring out how far they can be transformed.

“Art can be very serious, but it doesn’t always have to be”

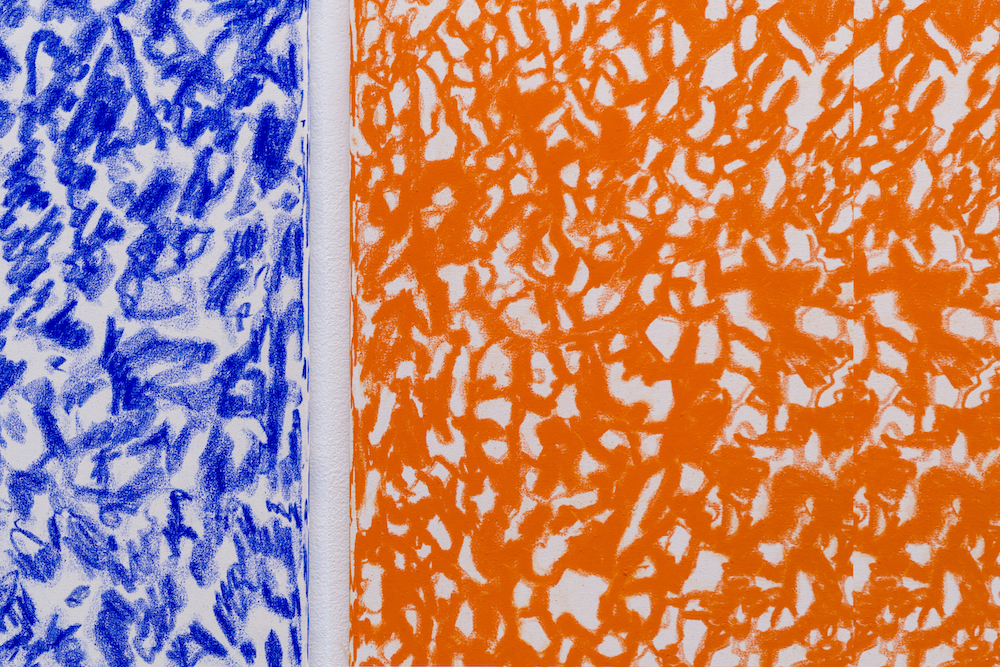

Many of the shapes which appeared in Playground were taken from very small details or forms in the playground, which then become a step removed from their original source and are presented more abstractly. What was your process for this? Do you begin by working from images, or is it more intuitive after a visit to a place?

I visited a lot of playgrounds to get inspired, and did research on Aldo van Eyck. He was a Dutch architect and essentially the godfather of playground designs in the Netherlands. Many people grew up with his designs around, even though a lot of them did not work out in the end and were removed. This is again where the concept of the contested space comes up. To me, ultimately, I want to take these shapes, these objects and forms that people recognize and understand collectively, and create something new with them. I want to open up these structures to new interpretation, to trigger imagination. Perhaps to allow people to rethink their idea of the playground, or to give them something to sharpen their senses and to enjoy. But that is really up to the audience.

You work feels as though it has an incredibly positive feel to it—is this something you want to project?

Art can be very serious, but it doesn’t always have to be. For instance, when I research Aldo van Eyck and visit playgrounds, plotting my new work and thinking about it, I am very serious about it. But that doesn’t mean the result has to be. I want my work to be something positive and happy, by transporting people back to the happy memories of being young, but also in general.

Do you feel the impact of Rotterdam on your practice?

I have been in Rotterdam for over five years now. It is a city that is very different from other cities in the Netherlands, because of the modern architecture and the open attitude towards reconstructing parts of the city. I think it is hard to be here and not automatically pick up something from that. It is also a place that is very open to artists, and provides opportunities to see, discover and show art. Kunsthal Light is just one such example.