In Wanderlust, Rebecca Solnit wrote that walking “can be invested with wildly different cultural meanings, from the erotic to the spiritual, from the revolutionary to the artistic.” Within art it has been used repeatedly as a tool for thinking about space, movement, history and even material inequality.

Walking is now invested with new meaning in the UK, as a daily walk has been pretty much the only time you get to lay eyes on something other than your interior walls. For two months I’ve been scrolling on Instagram through pictures of the previously unseen curiosities of my friends’ neighbourhoods, as the urge to document our lives and generate content continues, no matter how little we’re seeing.

If Charles Baudelaire’s flâneur had used a smartphone whilst wandering nineteenth-century Paris, he too would probably have snapped pictures of every weird bit of graffiti or dreamy window reflection. In the mid-twentieth century his legacy inspired the Situationists, led by Guy Debord, who developed the “dérive”. In this revolutionary strategy, one forgets about responsibilities and drifts quickly through the city via the “path of least resistance”, experiencing its contrasting psychogeographies, with the aim of opening ones eyes to the inequalities within one’s world.

“Walking can be invested with wildly different cultural meanings, from the erotic to the spiritual, from the revolutionary to the artistic”

In contemporary art, most accounts of the peripatetic begin with Richard Long’s A Line Made By Walking (1967), in which the British artist, waiting to hitch a lift, decided to walk back and forth across a field to trample an impressively straight line, which he then photographed as it caught the sunlight. Although Long’s aim was to make an artwork with nature, it was also seen as part of the turn to performance and the dematerialisation of the art object.

Long strolled out of Britain and exported his “walking as art” to Australia, Bolivia and the Himalayas, but, as Solnit writes, “the idea that all these places can be assimilated into a thoroughly English experience smacks of colonialism or at least high-handed tourism.”

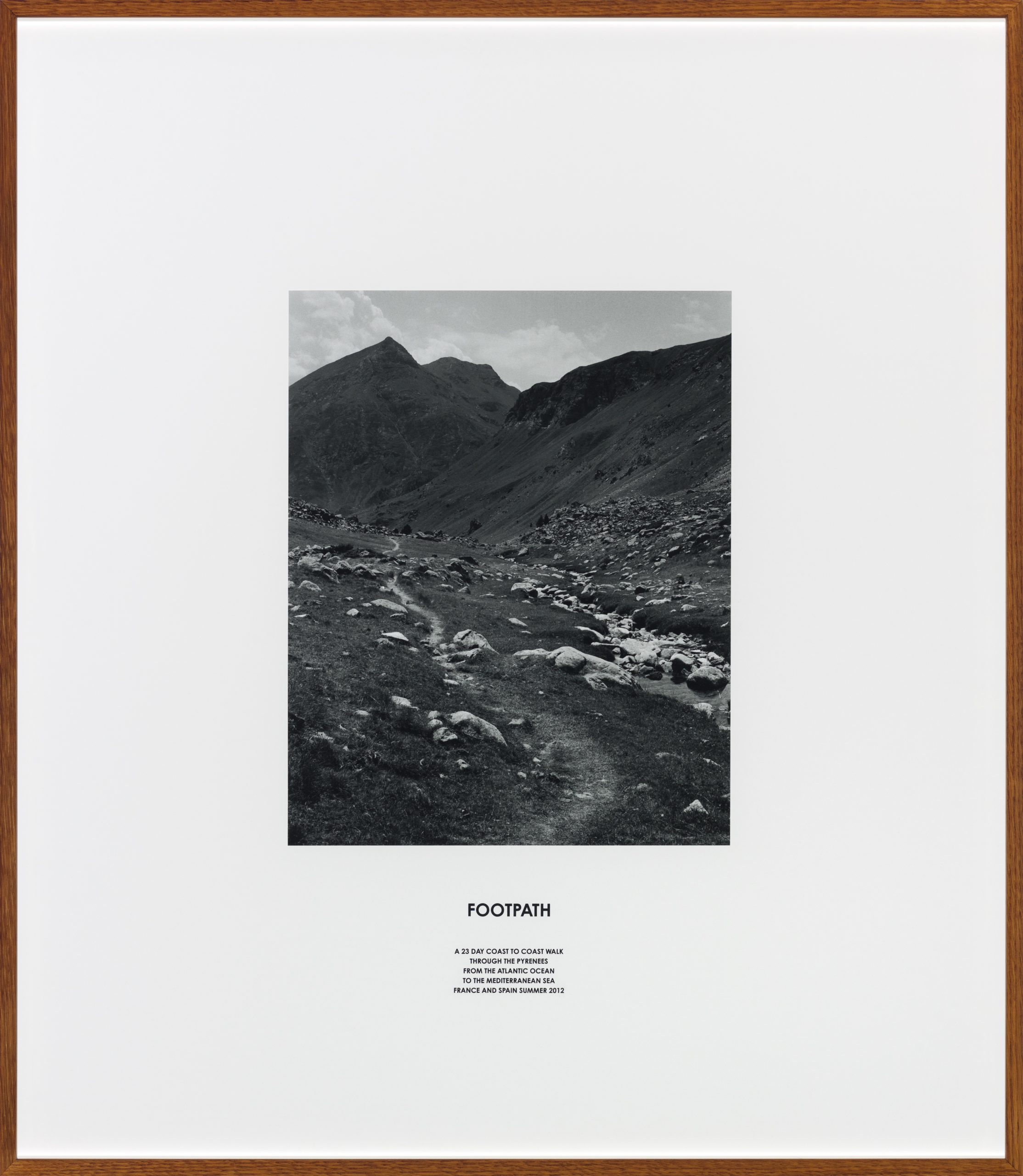

Concurrent with Long, another British artist has wandered a similar terrain. A self-described “walking artist”, Hamish Fulton was moved to use his wanderings as his sole inspiration after trudging 1,022 miles from Duncansby Head to Land’s End across forty-seven days in 1973. Fulton invites viewers to engage in his walks often via minimalist sculpture and photography, forcing some hard work on the part of the audience’s imagination—it is pretty difficult to feel the benefits of fresh air or a brisk walk through such ungenerous representation.

Fulton claimed, “If I do not walk, I cannot make a work of art,” echoing a rich literary and artistic history of walking as inspiration, and Kierkergaard’s insistence that he composed all his works in his head while wandering the streets of Copenhagen.

Courtesy Jon Rafman

When in 2007 Google embarked on creating an onscreen copy of the whole world, it became possible to stroll the streets from the ultimate spectator position. To engage in flânerie or submerge yourself in new surroundings, you simply open Street View. But you don’t feel the breeze in your hair, and only your fingers will benefit from the exercise.

Jon Rafman’s Nine Eyes is the most famous project to appropriate this online walking as art practice—combing the site for glitches and oddities. The screenshots are often beautiful, amounting to what Alec Recinos called “the post-internet sublime”. They are also uncomfortable: people with blurred faces become aestheticized as part of Rafman’s ogling vision. The work takes walking as a spectator to its limit, where the eye becomes the sole receptor of the experience, to unsettling effect.

“To engage in flânerie or submerge yourself in new surroundings, you simply open Street View. But you don’t feel the breeze in your hair”

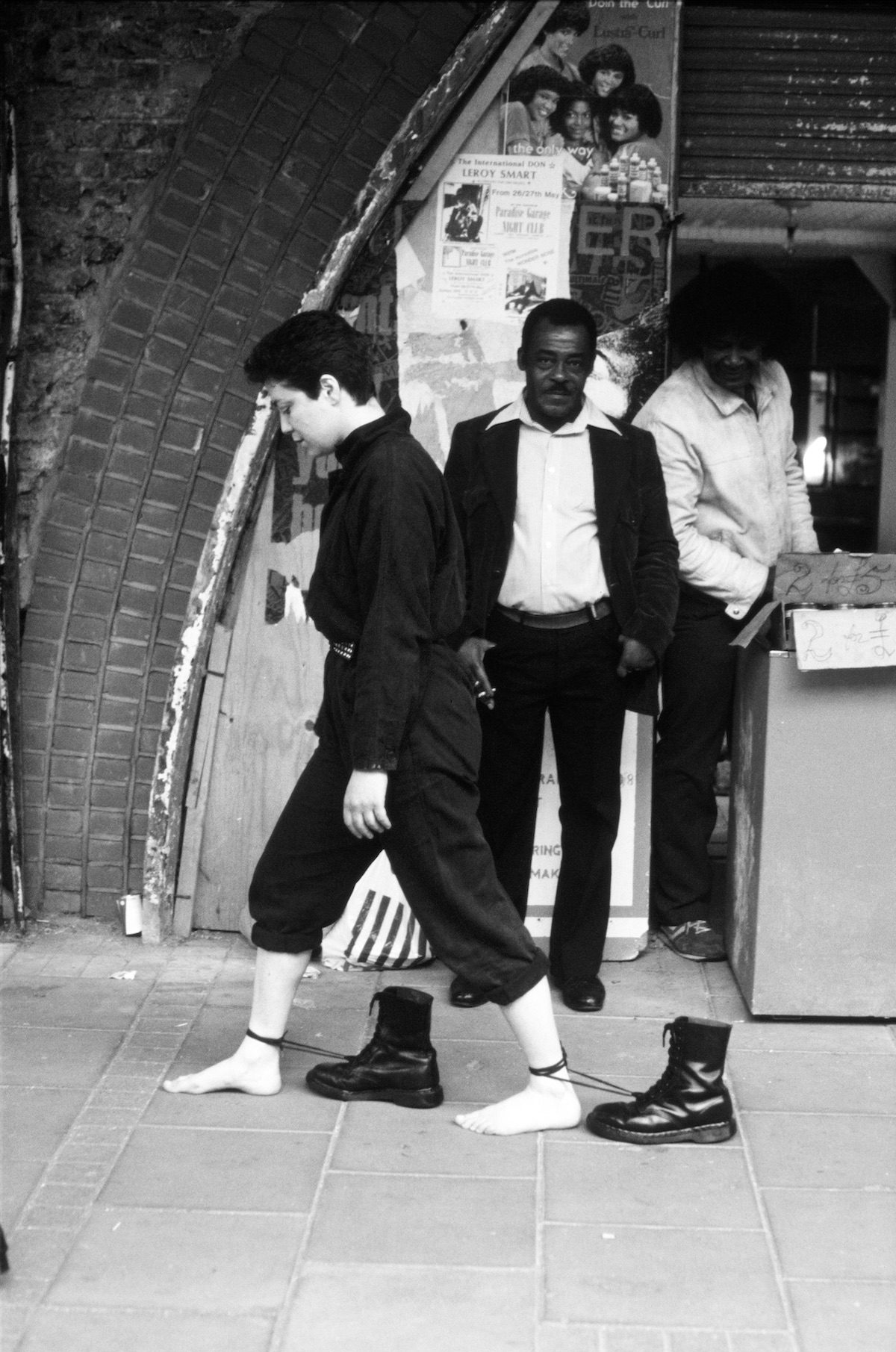

Mona Hatoum stepped away from the conception of the walk as a source of inspiration for the lone artistic genius when, in her performance Roadworks (1985) she walked barefoot through Brixton dragging a pair of heavy Doc Martens in her wake. The boots are synonymous with the early punk and skinhead scenes, but tainted by their later association with racist skinheads and their use by the police. Passers-by were not part of a spectacle observed by Hatoum; instead, they became an active audience in her painful performance. “I found that I was working ‘for’ the people in the streets of Brixton rather than ‘against’ the indifferent, often hostile, audience I usually encounter,

” she said. Here the body is engaged in the politics of the city street.

The early 2000s’ turn to socially engaged art brought walking to the fore in a big way. Janet Cardiff’s work Her Long Black Hair took participants around New York via a storytelling audio track and photographs—the solitary walk becoming a way to literally lose one’s self in a story. In 2005, Francis Alÿs explored London through Seven Walks: a project that, amongst other things, highlighted the prevalence of CCTV in the city.

The early 2000s’ turn to socially engaged art brought walking to the fore in a big way. Janet Cardiff’s work Her Long Black Hair took participants around New York via a storytelling audio track and photographs—the solitary walk becoming a way to literally lose one’s self in a story. In 2005, Francis Alÿs explored London through Seven Walks: a project that, amongst other things, highlighted the prevalence of CCTV in the city.

In an exhibition at Serpentine earlier this year, Hito Steyerl entered a space that was, prior to the show, funded by the Sacklers, and used walking to highlight the vast material and social inequalities present in the local borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Steyerl worked with the activist groups Disabled People Against Cuts, Architects for Social Housing and The Voice of Domestic Workers and artist Constantine Gras, who led free “Power Walks

” highlighting the work they’ve done in the area.

Disabled People Against Cuts also made the point of naming their contribution, in which they toured the sites of their interventions, the more inclusive “Power Tour,” since many would be participating in wheelchairs. Through this semantic difference, the accessibility of walking as a political action is called into question.

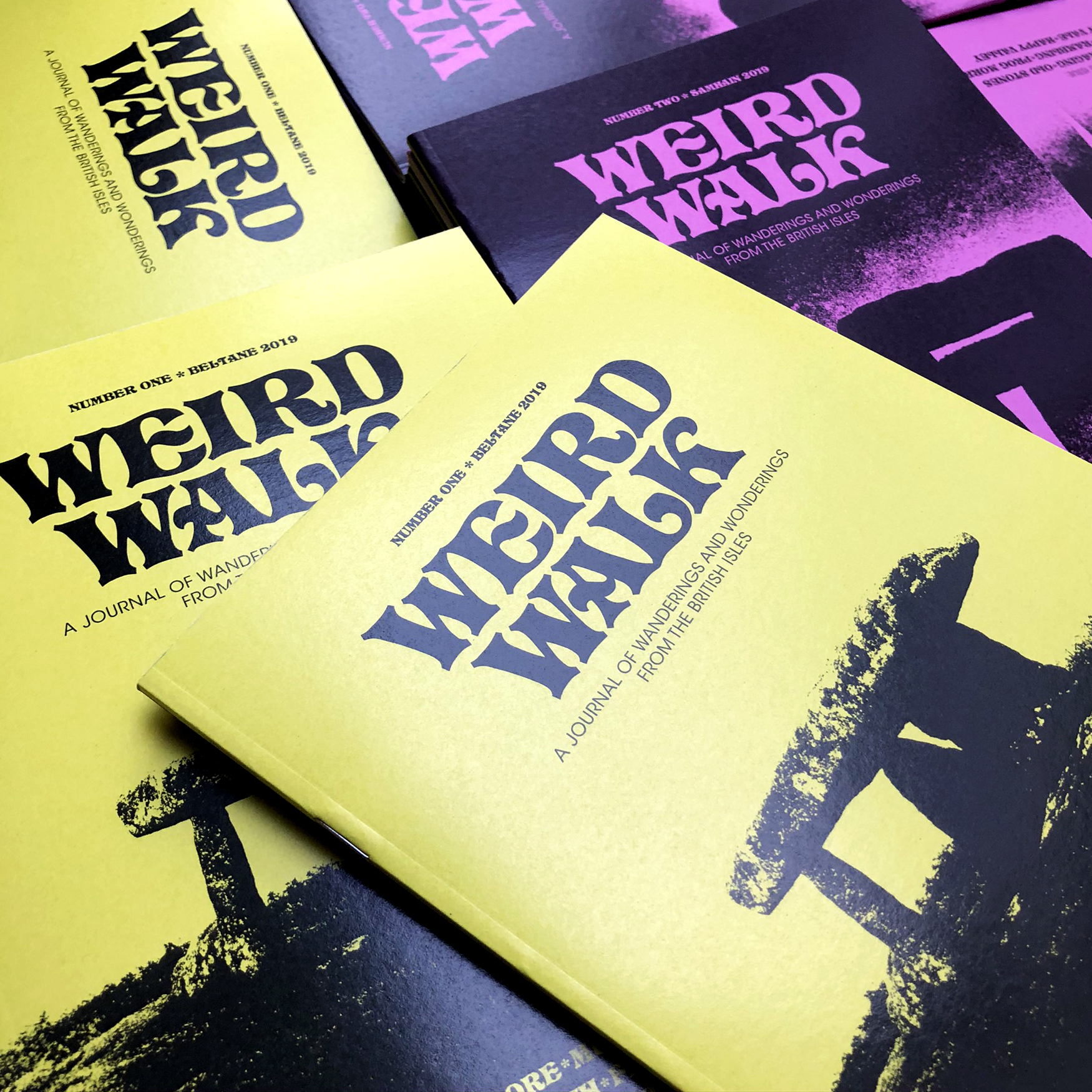

The ground we’ve covered here has largely been urban, but, for the three friends who released Weird Walk zine last year, rambling through areas of rural Britain has a magical appeal, bringing them into contact with ancient histories—imagined and real. Stone circles and medieval graffiti are brought together with 1970s psychedelia, evoking a more widespread desire to engage in the rural as an umbrella term for many differentiated places with deep histories and stories, rather than a mass of homogenous land.

“You soon notice the layers of history that are all around us. It’s more obvious when you are out in the countryside, but it’s also present in towns and cities,” they tell me. “Have a scan of an Ordnance Survey map of where you live and you’ll probably find a surprising number of ancient wells, burial mounds (marked on maps as ‘tumuli’), marker stones and hill forts.”

Artistic walking has evolved from a source of inspiration, to the artwork itself, to a practice of engaging politically, and even spiritually, with your surroundings. To borrow Solnit’s phrasing, the paths I’ve traced are certainly not the only paths. As lockdown restrictions begin to ease, those in the UK are permitted to meet one person in the park for their walks. What new meanings can arise when a solo stroll becomes one with a friend, whose face we may not have seen for months?