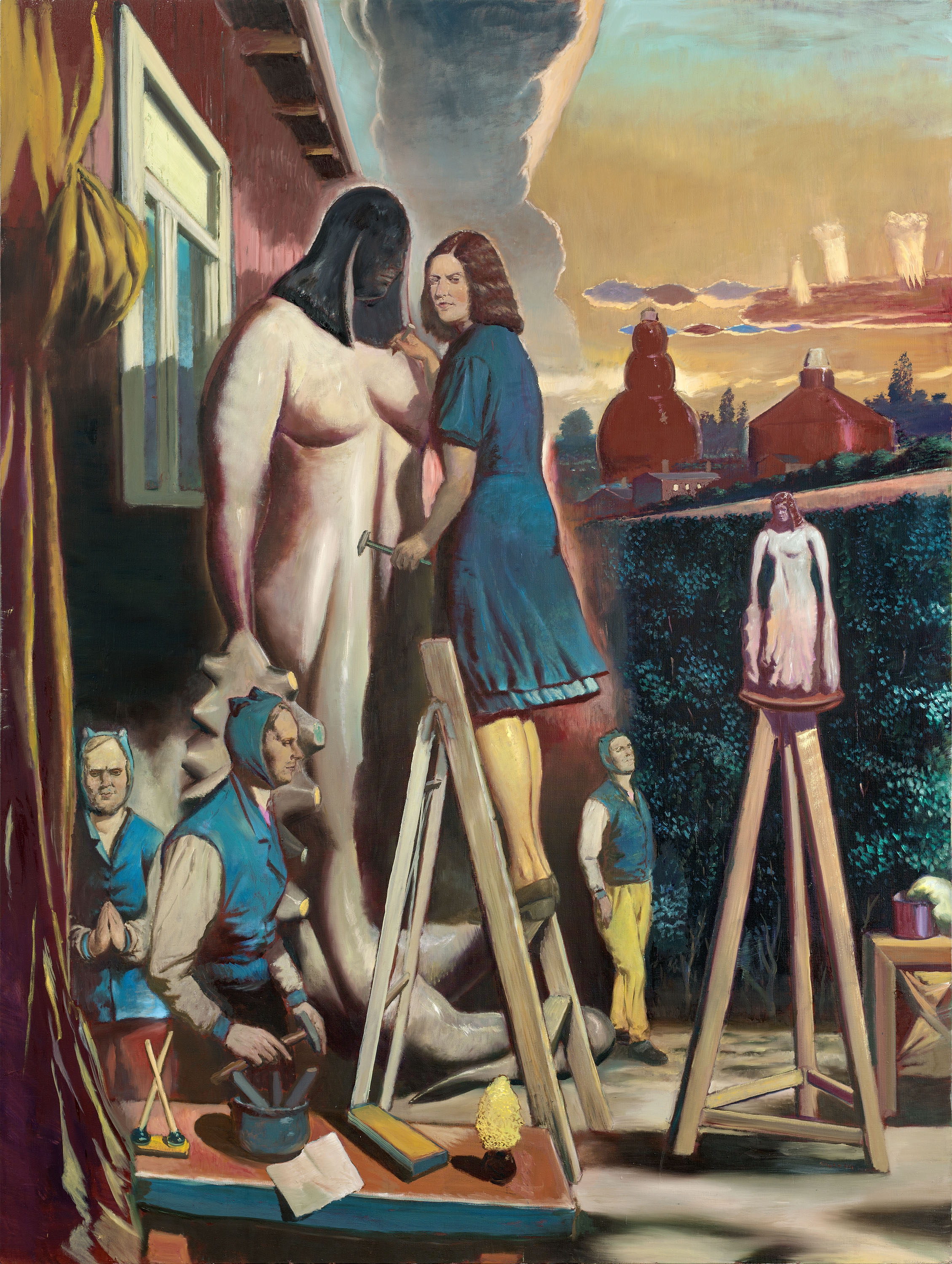

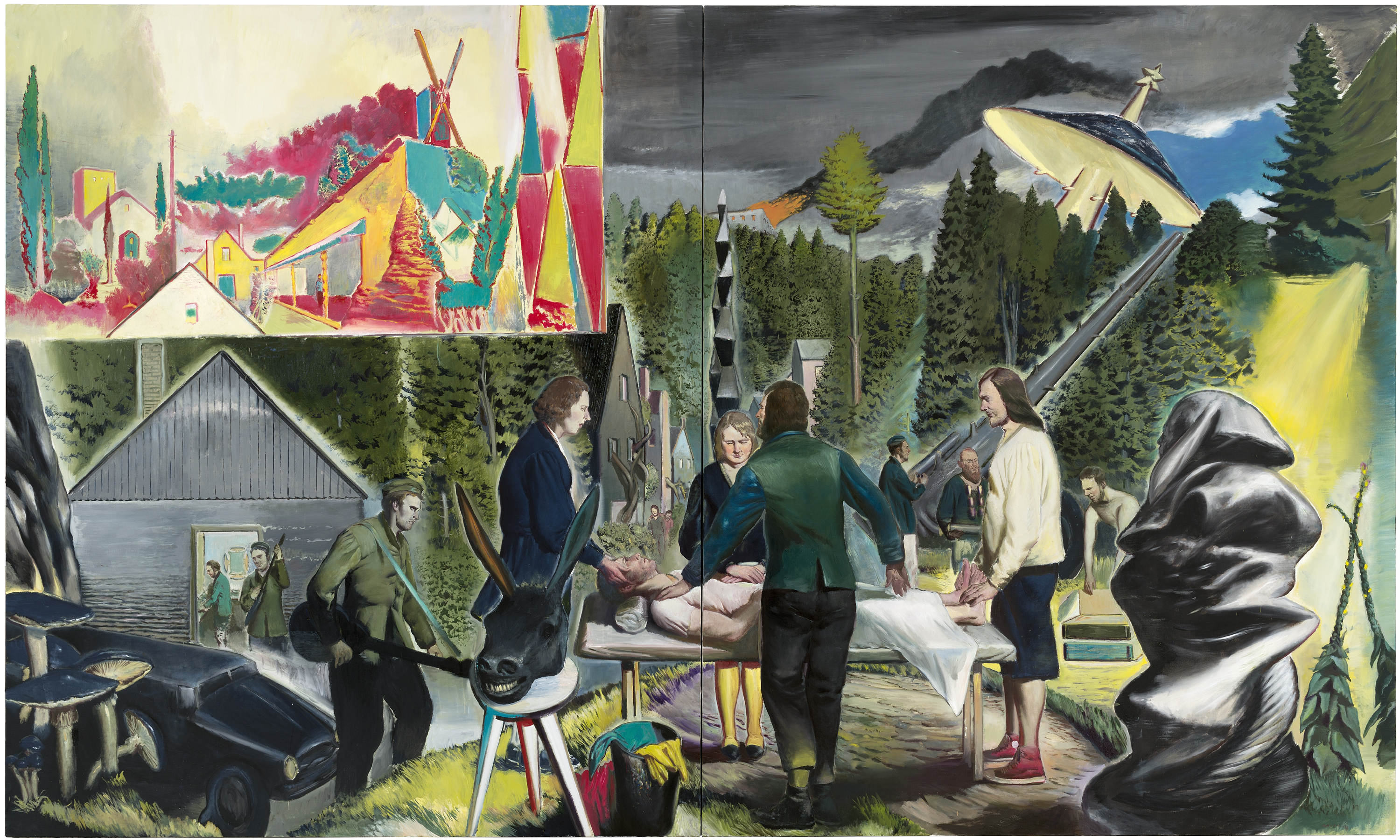

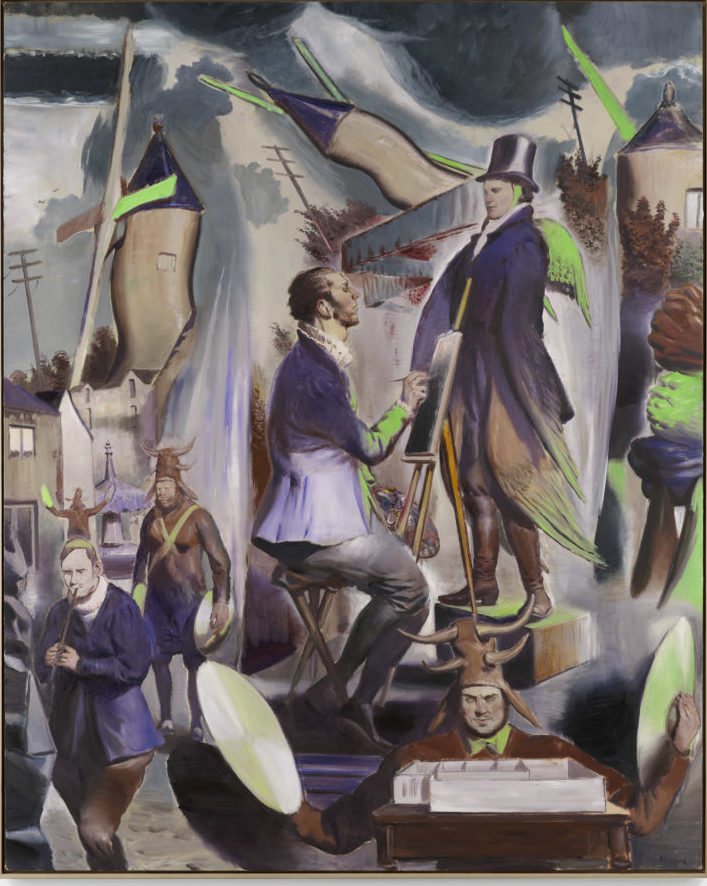

It’s easy to let go of meaning when we’re confronted with an abstract work. We might hunt for signs of emotion, the tension present in the artist’s hand when they created a particular stroke, but we rarely search for a solid explanation. It can leave us at a loss, however, when we view a work that provides a wealth of visual clues but refuses to offer up a real answer. Human figures, period costume, a historical setting and objects with obvious symbolic associations: German artist Neo Rauch piles these elements high in his paintings, but we shouldn’t expect them to fit together like neat little puzzle pieces.

“I feel like Max Beckmann who also had other people interpret his paintings,” the artist tells me. “I can place a trace that will lead to the centre of the painting but when you get there, you will see that it diffuses and goes into different branches. I’m trying to avoid nonsense painting and, on the other hand, I try to avoid painting with a certain critical intention, with a certain narrative background.”

The avoidance of “nonsense” is key. It is easy to avoid narrative and interpretation if the painting itself makes an overt display of its unmeaning. But Rauch’s paintings seduce us with apparent facts, figuration, times and events, confidently pulling us down a path with no end. It can make for uncomfortable viewing, finding yourself diving for clues despite knowing full well (if you’ve attempted such a search previously) that they lead nowhere. There’s a silence that’s difficult to sit with, a command to shut off reason and succumb to the inner ambiguity of the work itself, while it appears to call for the exact opposite: to be understood.

With such a wealth of specific detail in the work, I wonder if Rauch himself is tempted into interpreting his own imagery. “This can happen,” he says, “but it’s not my intention to put meaning into it. My intention is to create creatures. A good painting has to be able to live when it leaves the studio, it has to be able to survive under certain conditions and it is necessary to give all the things away that are important to keep it alive. Like a creature it has to have bones and nerves and muscles and a brain and a heart, but that’s as far as it is meaningful.” This visceral way of speaking highlights a Romantic tendency in Rauch, which is nonetheless offset by self-possessed poise.

The following day, while addressing a sizeable crowd of London press and gallery patrons at the opening of Rondo at David Zwirner, he suggests that many of the works come directly from a depressive state. It’s easy to see how the very unreason of depression could exist in these pieces. There is no desperate agony visualized, but a sense of uncertainty, a world turned on its head in which it is difficult to get a firm footing. The colours too offer a complex and original view of the turbulent human mind—blacks and reds would be too crass; instead there are soakings of aubergine and bright orange.

“Socialist Realism influenced my subconscious and it was part of the work that surrounded me when I grew up”

That said, the works should not be viewed as a straight projection of his inner workings. “In a certain way,” he tells me when I ask if his own dreams feed into the works, as has often been presumed, “but not so directly. I used to sleep very badly, so when I’m painting, when I’m preparing an exhibition and the opening comes closer and closer, I become very nervous and the patients in the pictures—I call [the figures] patients sometimes because they expect a certain treatment—come and they shake my bed. This is terrible and I almost feel that I cannot paint anymore, I’m just a newcomer or a starter or a student. There’s always this kind of fear that tortures me to fail and that colours my dreams and influences them.

“But on the other hand, it doesn’t work so well to use dreams for paintings. I’ve done it sometimes but not so often. I try to simulate the mechanism of dreaming. I have used only dreams that I couldn’t resist. I did it much more often in my early years, but I figured out that this way is dangerous. It could end in a kind of kitsch painting. But in my subconscious, there are of course many images of reality that surround me, which I grew up with, and this is the treasure that feeds my painting.”

Rauch was born in 1960 in Leipzig, where he continues to work. His parents were killed in a train accident when he was only four weeks old and he was raised by his grandparents in Aschersleben, Saxon-Anhalt. His paintings still bear traces of the Socialist Realism that was prominent at that time, influenced by the Soviet Union’s hold over East Germany. “There was most definitely a time when I was using, and flirting with, Socialist Realism,” he says. “There were definitely some elements but mainly it influenced my subconscious and it was part of the work that surrounded me when I grew up. In the early childhood, you don’t reflect the world by thinking, you keep all that stuff that surrounds you in the inner treasure of memories and later, twenty or thirty years later, it comes out on the surface and that’s what happened in my work in the 90s and later.

“But I guess this influence is not so strong anymore and the Socialist Realism was, during my studies, not such an important thing; even for my teachers it was quite over. Much more important was the figurative painting that happened outside of the Socialist world and we used to underestimate this. In Great Britain you had an unbroken tradition of figurative painting that was not connected with any political intentions—Frank Auerbach, Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud—that was much more important for us, to know: Ah, there are painters in the Western World who don’t paint abstract, like in West Germany and in France. That’s why the British painting scene was interesting for us.”

While Rauch comes across as a harsh critic of himself, he seems little swayed by the outside world, by the opinions or styles of the moment. “Don’t ask me things like this!” he laughs when I question him about the way the reception of his work has changed in recent years since figuration became more fashionable again. “I’m not responsible for that.” Likewise, he says his own increasing star status has had little or no impact on his practice. “My studio is my castle and I’m very safe there away from the razzle-dazzle of art fairs and all the stuff that could disturb me.”

“My studio is my castle and I’m very safe there away from the razzle-dazzle”

Although colour plays an enormous role in his work now, there was a point in the early 90s where he removed it almost entirely to focus on form. “Before I made this decision I was in danger of being an abstract Sunday painter,” he mentions. “Very kitschy, lots of colours, very thick paint on the canvas. I saw a black-and-white reproduction of one of my paintings and I didn’t see any structure, it was just a plate of soup, so I decided to change this radically. I used only black-and-white and a little bit of brown, and that was my rescue.

“I had a dream before this decision and it was a very strict, advising sort of dream. I dreamt that I was in a big hall with square-shaped walls, like a cube, but very huge, very high, and on the wall was a big mandala. The whole wall was covered and it was black and it was very structured, it was made of iron and in the middle was a very small swastika—not the political swastika, the Buddhist sign. I’d never seen a thing like this before, it definitely came from the collective subconscious. So I changed direction and I painted the big tondo [Plazenta, 1993], and that was the start.”

“It was a hard and strict decision and I was sure I would come back to colour,” he continues, “but carefully. I decided to let colour start floating into the shapes that I created in black and white, and that was definitely my salvation.” These days, colour is a crucial element in his practice. Often a painting will be dominated by one or two tones, and there tends to be an unsettling use of natural with unnatural colours—in his 2014 work Marina, for example, the roofs, clock tower and jackets of many of the figures are all washed in a vibrant minty green, against peach flesh, brown rocks and a dark blue sea. Human scale will often be used to disconcerting effect too, as in 2008’s Die Aufnahme, in which an orange-clad, muscular woman drags a man half her size determinedly down a street, surrounded by a sprinkling of pint-sized figures going about their daily, if slightly unusual, business.

I wonder if the figures come from his subconscious or whether they are interpretations of people he has come across in life. “They come out of my wrist,” is a typically wry Rauch response. “I develop them on the canvas and sometimes it happens that I’ve painted a very fabulous portrait and I walk back and I have to decide to fire this person out of the painting because it doesn’t fit or make the right connection. So I have to decapitate the figure and try it again.”

For Rauch, really “understanding” a painting stops it from enduring in the mind of the viewer. Almost as though once we’ve “got it”, we can tick it off and move onto the next. “It’s just a short effect on the eyes and you’ve forgotten it,” he explains. “It may have been that you went into an exhibition that you were fascinated by, and the moment you left it you had forgotten it. And you also couldn’t describe what you’d seen. I would like the viewer to take something from it but I have to put certain qualities into it so that they don’t see it as just a painting. An icon. It has metaphysical qualities and it will go deep into the subconscious of the viewer.”

This feature first appeared in issue 30

BUY ISSUE 30