On 17 November 2017, 20 researchers from the Media Lab at Massachusetts Institute of Technology posed excitedly in front of a specially modified Boeing 727 at Sanford International Airport in Florida. Wearing navy blue boiler suits with American flags emblazoned on the sleeves, the group of graduate students and researchers—all part of MIT’s Space Exploration Initiative—were about to embark on a zero gravity flight. Their self-declared mission? To democratise access to outer space. In practical terms, they were eager to test out their various projects and creations in a fully weightless environment: from a modified rowing machine, to a seahorse-inspired robotic tail designed to assist astronauts with mobility.

Nicole L’Huillier’s project was a futuristic musical instrument called the Telemetron, a basketball-sized dodecahedron chamber containing gyroscopes which react to the structure’s positioning and movement. Sensors record the object’s motion, and then create a corresponding musical composition. By directing the Telemetron through the plane’s anti-gravity fuselage, L’Huillier and her collaborator Sands Fish would, in theory, be able to acclimatise to the weightless environment and “play” the instrument as it floated through space. In reality, she says, the experience of anti-gravity was so peculiar and disorienting that the prepared choreographies were abandoned almost instantly. “You don’t understand how to move,” she remembers fondly. “Your brain and your body are recalibrating constantly. Once we were in the flight, nothing we prepared on Earth worked; it was just completely random.”

- Telemetron. Photo by Steve Boxall

“Your brain and your body are recalibrating constantly. Once we were in the flight, nothing we prepared on Earth worked”

The pair’s ambition was to investigate what it means to create art in outer space: who is permitted to do so; what the innovations might look like; which earthly laws of creativity are adhered to and which are overthrown. Working mostly across experimental sound design, receptors and robotics, L’Huillier’s work also poses questions about agency and movement on Earth: what is the relationship between the programmer and the robot? How can sound be understood as an architectural building block? And in this context, how far can the traditional limits of composition and construction be pushed?

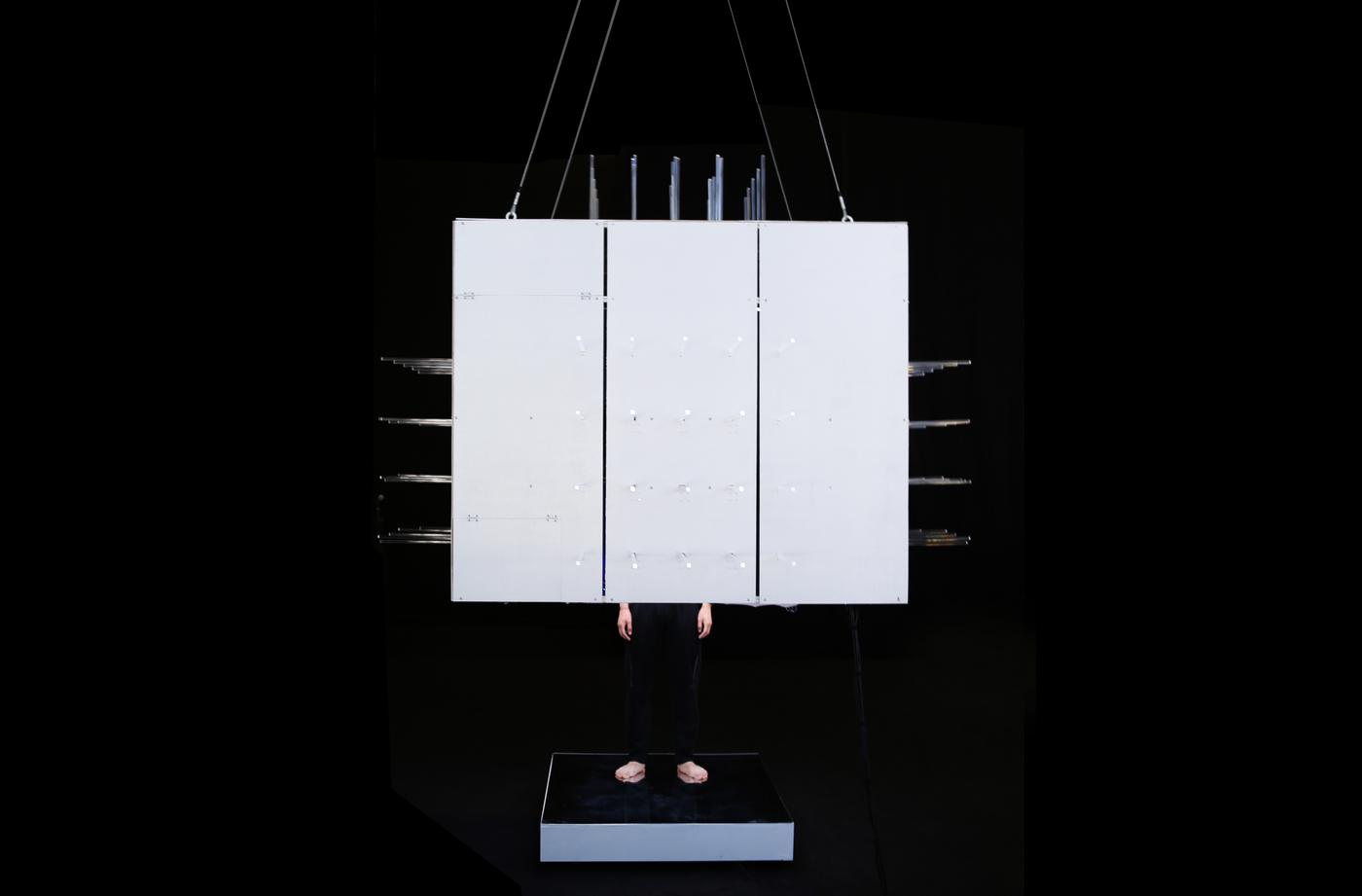

L’Huillier constantly investigates ideas of technological causation: the fluid relationship between stimulus and response. For her MIT masters project, she created Spaces That Perform Themselves (2017), a multi-sensory musical incubator for a person to stand inside. Acrylic rods, each fitted with a stepper motor, protrude into the fabric walls, giving the controller the ability to alter the geometry of the space from the outside. LEDs in the wall mean that light can also be modulated, while a low frequency transducer at the bottom of the structure creates deep, rumbling vibrations. It sounds overwhelming, but L’Huillier is as concerned with the concept as she is the participant’s experience. “The project explored ideas of spatial choreographies,” she explains. “The idea of composing with this palette of sound, vibrations, colour and movement together.”

L’Huillier has been experimenting with this palette since her childhood growing up in Santiago, Chile. Born in 1985, she quickly developed an interest in the drums from her older brother, often peering around the door as he and his friends practiced in teenage bands (later on, many of the artist’s friends played in what she remembers to be “very bad punk groups”). But 1990s Santiago was “a very old-school place”. She was met with confusion from her peers when she showed an interest in the drums—though they happily danced to the Spice Girls together. She gradually drifted towards the city’s flea markets, buying up broken turntables and tape recorders and reassembling them, but not yet understanding the formal elements of musical composition. Instead, experimentation became a form of classical training. “I became very aware of the language of circuit bending, for example, without being fully aware of what it was,” she says. “It was more, ‘Let’s fix this thing and see what happens. If I change this knob the sound is different.’ And then thinking, ‘How can we record the sound?’”

- Hybrid Radio performance. Photo by Gabriele Urbonaite

“Despite a traditional curriculum, architecture school was transformative for the artist because of a single realisation: that, like bricks and mortar, sound and space are compositional materials”

L’Huillier’s parents, a civil engineer father and catering manager mother, encouraged her interests in painting, music and photography, but she eventually applied to architecture school at the University of Chile, a decision she links in part back to Santiago’s subtly gendered conservatism. Despite a relatively traditional curriculum, the period was transformative for the artist because of a single realisation: that, like bricks and mortar, sound and space are compositional materials; designed and constructed in certain ways, they can facilitate various dynamics and relationships, just like a physical structure. A year-long academic exchange to Paris introduced L’Huillier to the Musique Concrète of Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry, while she also drew inspiration from artists like John Cage, developing “an understanding of sound as detached from music”, and “the idea that silence is also sound, and that things and objects are also musical”, which also informed an interest in acoustics and theatre design.

She now makes music as both a solo artist and as one half of the space-pop duo Breaking Forms, often giving her sound installations an afterlife by releasing the recordings as solo tracks. Ephemeral Urbanism: Cities in Constant Flux is a ten minute long ambient soundscape, originally commissioned for a pavilion curated by Rahul Mehrotra and Felipe Vera at the Venice Architecture Biennale in 2016. Starting with a hopeful, extended synth line, the track gradually darkens as strict loops and garish industrial sounds interrupt its initial flow; the bustle clears halfway through, giving way to high-pitched strings while a dampened lo-fi drum bubbles underneath. Breaking Forms deal in an accessible brand of electro-pop, though they are by no means limited to synths and 1980s big beats—there’s still room for the occasional Philip Glass cover. Their track Ask Me Now, released in 2017 on a sparky Chilean label compilation, is layered with a trap-like drum line before L’Huillier’s vocal muscles through.

Beyond her music, L’Huillier’s work has to be understood within the creative contexts of the Media Lab she calls home. She talks about the space as a kind of sanctuary for creative misfits, those whose research interests are too wide for traditional compositional academia. “I felt so fragmented and alone in the world,” she says of her isolated youth spent playing electronic music. “But here, everybody feels that. We’re all alone, but together.” Programmers, designers, artists, technicians, psychologists and scientists assemble as part of approximately 30 research groups. Upon entry, students then have the opportunity to become paid research assistants for senior academics. Currently pursuing her PhD, L’Huillier is part of the Opera of the Future group, which “explores concepts and techniques to help advance the future of musical composition, performance, learning and expression”.

“I felt so fragmented and alone in the world, but here, everybody feels that. We’re all alone, but together”

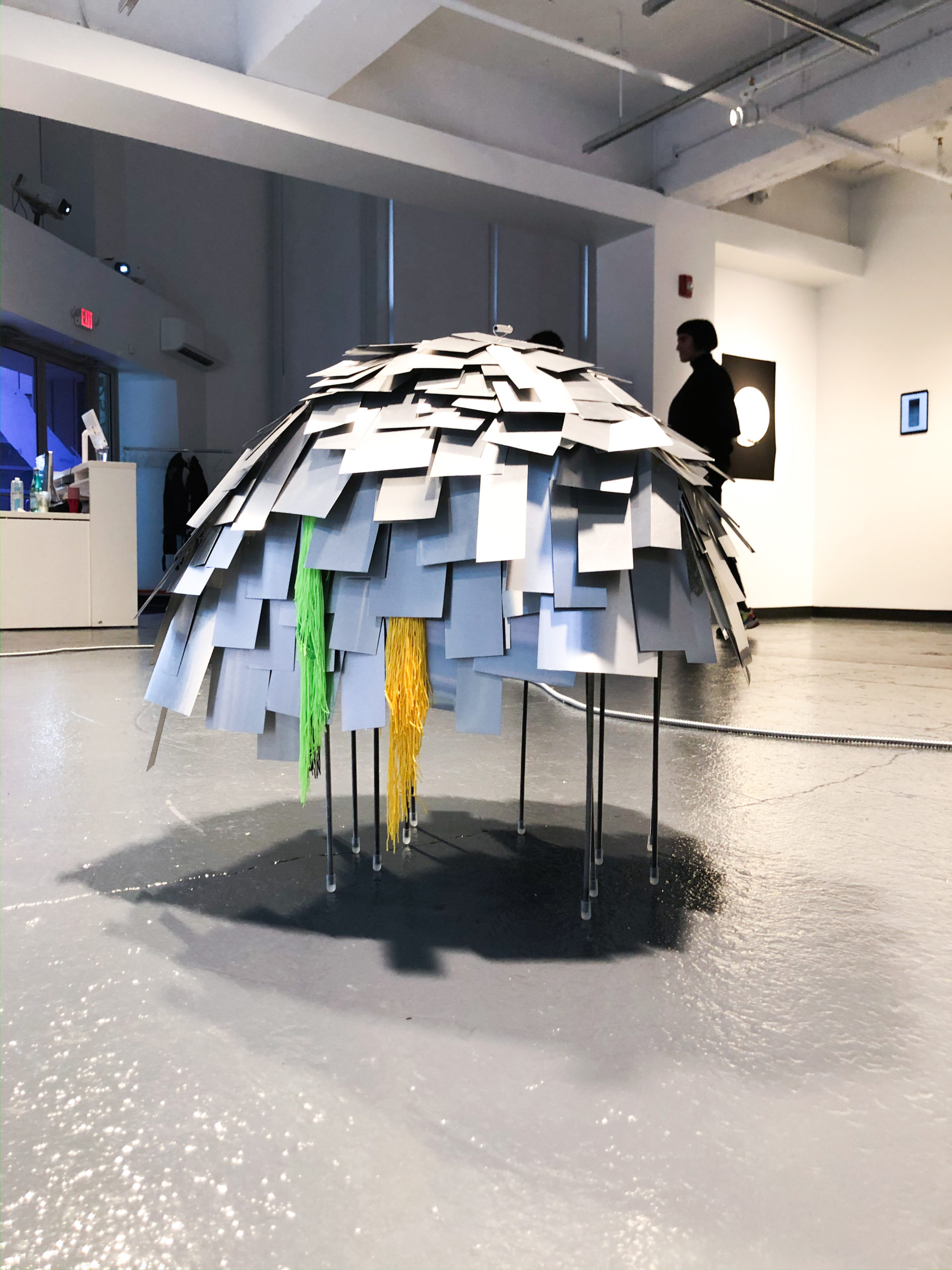

Conversations with fellow students encouraged L’Huillier to view her work on robotics not just in terms of inputs and outputs, but also in relation to energy transfers, performance and kinetic theory. Two works in particular: The Dancer (2020) and Ritual I: The Thing Itself (2018), show her understanding of sound and movement as randomised and uncontrollable forces, even when systems are carefully designed. The Dancer is a standing robotic structure which moves across the floor, triggered by sounds emerging from its own body. Supported by thin metal tendrils, the upper section resembles a mop of hastily arranged slate tiles, while strands of draping coloured fabric enliven its flanks. Given The Dancer’s self-sufficiency, L’Huillier wanted to interrogate “how the space is also a performer”, she explains. “What happens when the space is not the static container of an experience, but the space is a dynamic motivator, and yet another agent of experience?” she says excitedly. Ritual I: The Thing Itself was a precursor to these questions, itself a spiked metal structure in constant flux, tracing repetitive patterns through constant vibration.

What emerges when speaking with L’Huillier is her conception of her art as just one manifestation of a broader understanding of space and sound. With sharp perceptiveness, she turns her attention to the world around her, theorising it via simple but enchanting theses: “Everything that is matter has the capacity to vibrate and resonate,” she explains. “And by this resonance and oscillation, matter is actually interconnected via sounds, via the waves that are touching each other.” She uses our video call as a further example: “Right now we’re at a distance,” she gestures. “In the world today, we’re reformulating what distance means in many ways, socially and politically. But right now, I’m touching you with my voice. I’m touching you with the sound. I love the idea of how everything is in constant dynamism, and the world is restless, in a constant relationship of frequencies and resonances.”

- Delira. Photo by Benjamin Matte V

Despite the technological complexity of her work, L’Huillier is also influenced by myth and cosmic mysticism. Her sound room Delira, curated at the Chilean National Museum of Fine Arts in 2019, was inspired by the Lyra constellation and the myth of Orpheus and Bacchantes. Horns and cymbals layer over each other around the room, triggered by their own vibrations and manual inputs. The result is a hybrid of sound design and classical iconography, a playful departure from L’Huillier’s more academic work. Her range also emerges through a recent refocusing on her heritage. She concedes that during her years at MIT, she’s grown distant from Chilean influences and modes of thinking, instead pre-occupied with the insistent futurism of the Media Lab. “It’s often been hard to place myself as an artist,” she admits.

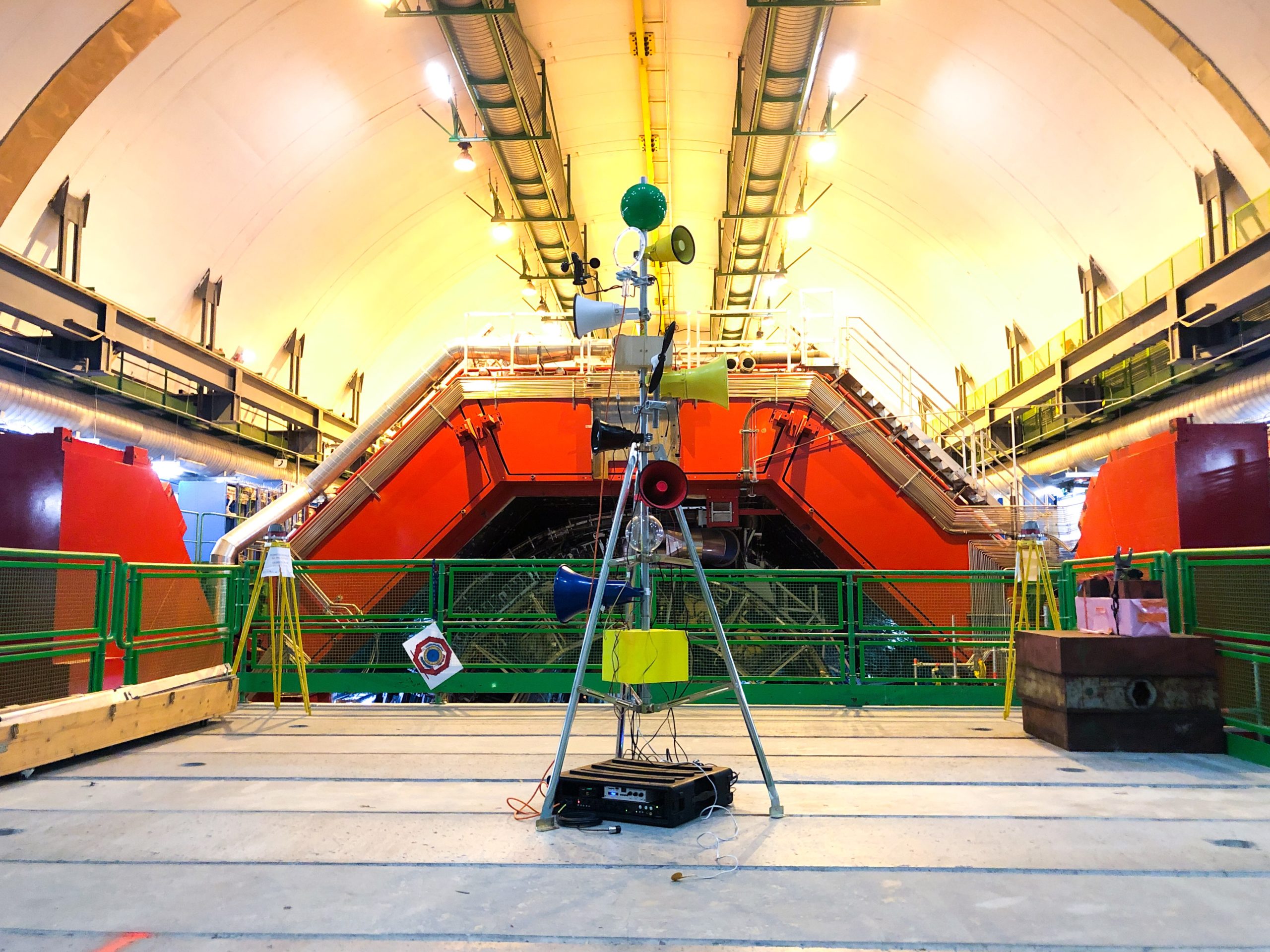

- El Poema de la Fabrica Cósmica. Photo by the artist

El Poema de la Fabrica Cósmica, a major international project as part of L’Huillier’s 2019 Simetría Residency, allowed her to explore this link between Chile and the cosmos, bridging the gap between her own past and present. She designed a listening device called the Para-Cantora and toured it around three locations, each a cosmic frontier in its own way. She travelled to CERN in Switzerland, the ALMA Observatory in Chile’s Atacama Desert, and the Paranal Observatory, also in the Atacama. “It’s a series of listening sessions,” L’Huillier explains, “concerts in these very iconic places where we’re already unveiling new realities.” Some of the Para-Cantora’s sensors are microphones, some electromagnetic antenna to pick up the fields produced by the surrounding equipment. There are also non-sonic sensors which monitor data like altitude, pressure, temperature and wind. L’Huillier creates a set mapping for each, assigning a sound, synthesiser tone or voice to each metric. Because the programming is the same across all three locations, the soundscapes are direct transpositions of how the environments vary; there is musical confirmation of CERN’s situation 100 metres underground from the resulting concert.

“In the world today, we’re reformulating what distance means in many ways, socially and politically. But right now, I’m touching you with my voice. I’m touching you with the sound”

“The piece is about how to create a ritual of listening: solemn moments of paying attention to things that we cannot usually access because of our limited human perception,” she says. Unlike the majority of her robotic projects, here “the Earth itself as an apparatus”. The unknowability of outer space adds yet more intrigue to a project which already plays an important role in connecting her to Chile’s cosmic history, especially via the belief systems of the indigenous Mapuche population. She returns to the idea which informed the Telemetron—that of democratising outer space—but it now feels more precise, oriented by her focus on Chile’s specific history.

Having studied the intimate relationship that indigenous peoples have with the cosmos, L’Huillier is angered by the monolithic discourses of space travel, especially around the idea of colonisation. “It’s the Western enterprises that are building the language and the history around space exploration,” she says. “But theirs is not the only language, and it’s not the only history”. This recognition of multiplicity is the essence of her practice: as an artist, she is both an intricate programmer and a restless observer: endlessly innovative in her vision of what robotics can achieve, but also eager to embrace its occasional randomness and unpredictability. The infinite possibilities of movement, sound and space are a yet-to-be explored universe of their own. From her apartment in Boston, L’Huillier is plotting a vast expedition.