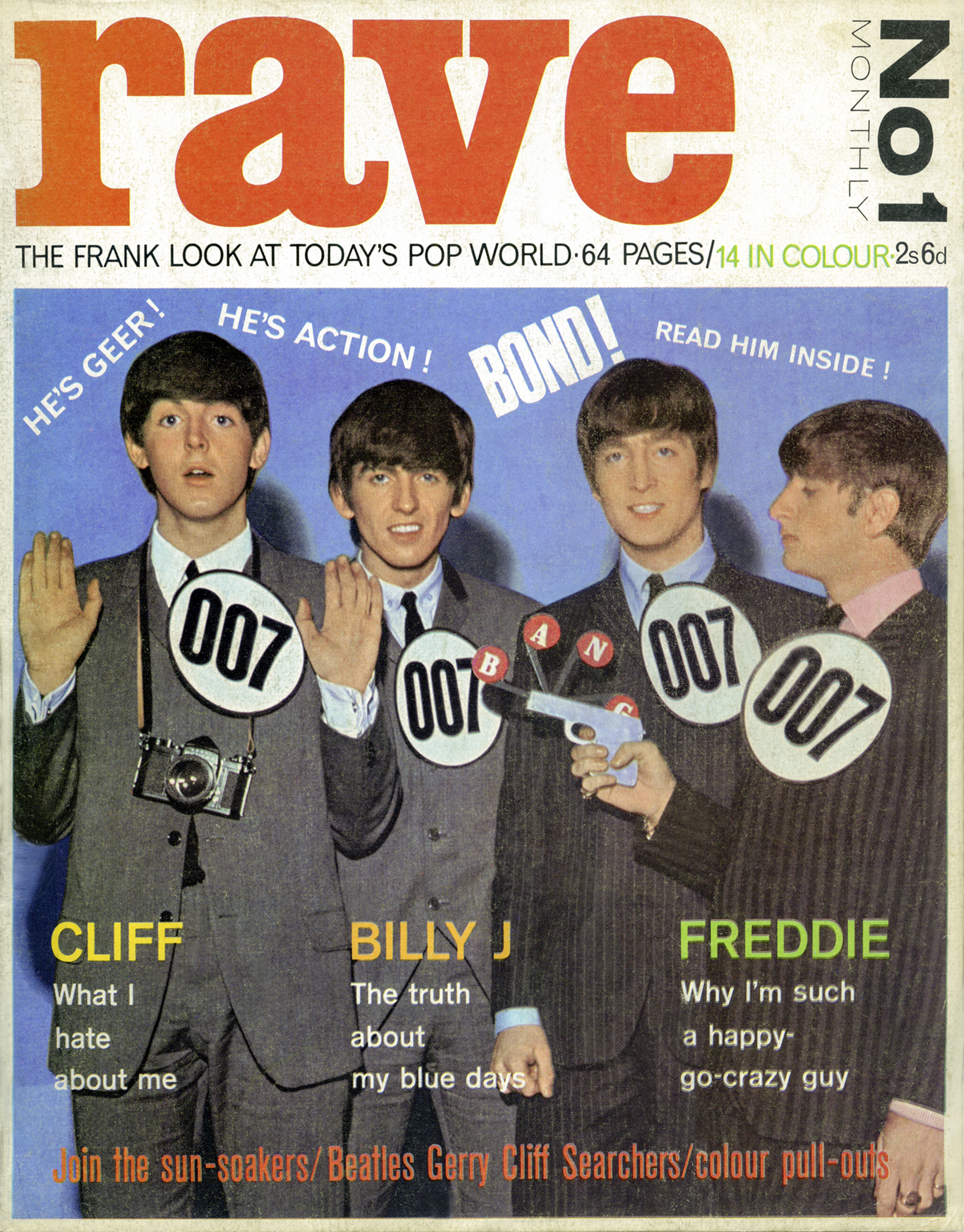

Rave culture has taken a pretty wild trip over the decades. From its earliest stirrings—“raves” apparently first came to mean hedonistic parties in the post-WWII jazz and rock’n’roll scenes—to its late-1980s Balearic epiphany (and a succession of awakenings ever since), raving has shape-shifted from underground expressions and acts of creative rebellion, through mainstream and branded recreation, high fashion and heritage statements.

In the past few years particularly, raves, clubbing and nightlife have become a focal point of formal art gallery and museum collections, with fascinating (and frequently surreal) results. Sweet Harmony at London’s Saatchi Gallery is the latest major exhibition, following events including Night Fever (at Vitra Design Museum in 2018) and Club to Catwalk (V&A London, 2013). While many arts institutions, from London’s ICA to New York’s MoMA, have hosted club events, we’ve now reached a point where clubbing and raving is acknowledged as part of culture, and not merely a throwaway phase.

Nostalgia is obviously a driving force here; it’s now thirty years since the “second summer of love” associated with Britain’s acid house explosion. Sweet Harmony’s subtitle “Rave I Today” nods to its broader take: on the scene’s lasting power and contemporary significance; its associated names include numerous genuine movers and shakers of British club culture, and its publicity material has been fun (including street posters that blend in alongside “regular” nightlife flyers). Still, Sweet Harmony itself evokes more than one massive club anthem of the same name (Liquid’s 1991 piano banger, or the Beloved’s chilled 1993 tune), and there’s no denying the heady nostalgic haze that hits you as soon as you walk into the first darkened gallery room.

“Nostalgia is obviously a driving force here; it’s now thirty years since the ‘second summer of love’ associated with Britain’s acid house explosion”

For anyone that grew up clubbing—or grew up inspired by rave culture, from a distance—the sight of a petrol pump (glowing centre-piece of Colin Nightingale and Stephen Dobbie’s Getting To The Rave installation) produces an incredibly evocative hit: about trawling the motorways in search of a free party (an experience also brilliantly portrayed in the recent Scottish coming-of-age film Beats), or any personal route to the club. For me, it brought back the mid-nineties trawl to all-nighters at Bagleys Warehouse in Kings Cross, past a service station buzzing with clubbers; back in the twenty-first century, it also brings to mind Elephant’s own Elephant West venue (a converted petrol station turned gallery and live music/dancefloor space).

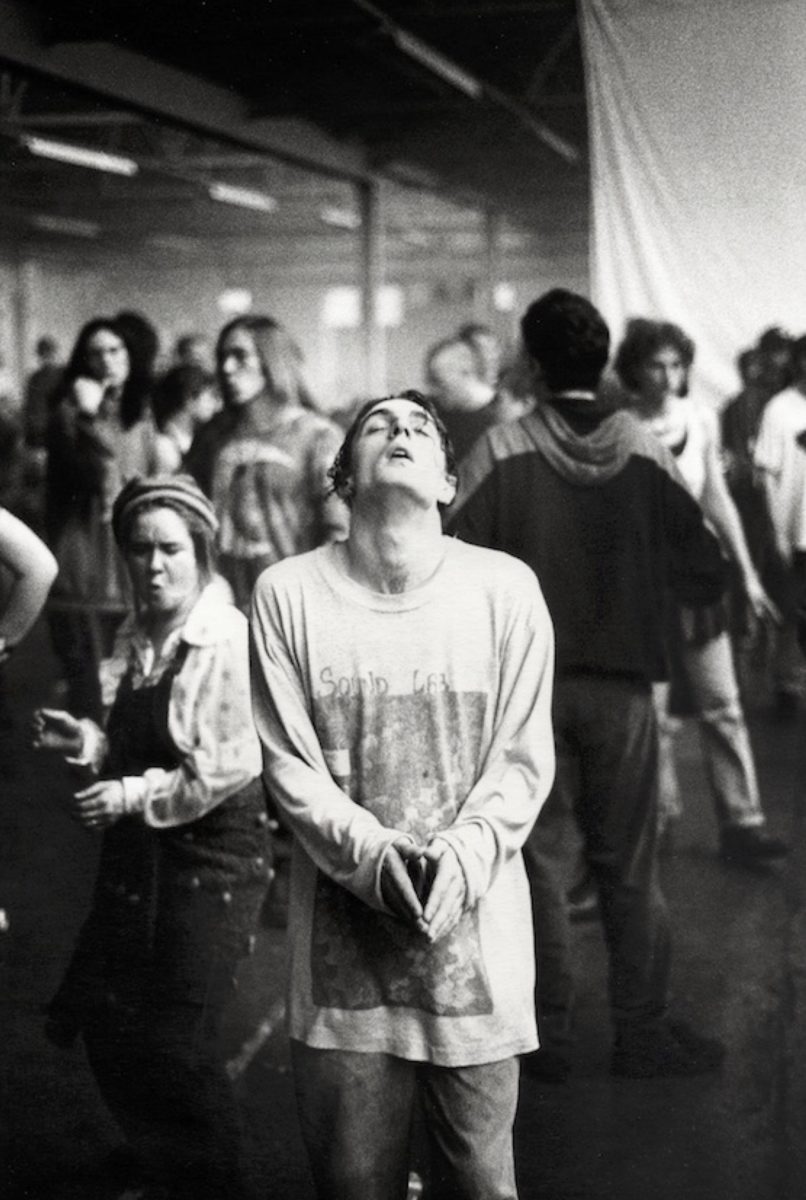

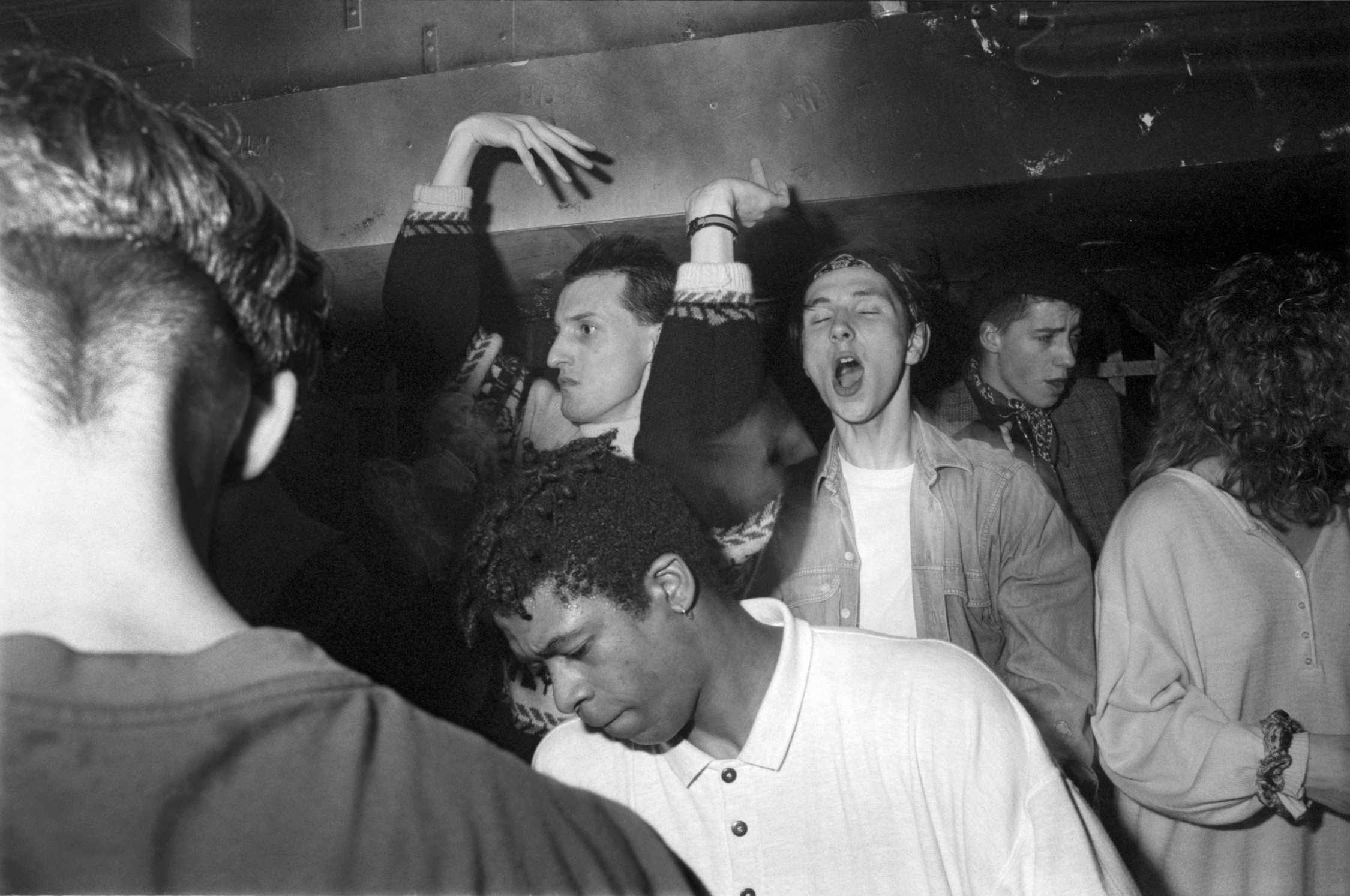

It’s on. The anticipation swells as you step through a chain link fence, through a painted smiley portal, into a room of Dave Swindells’s superlative club photography, and James Alec Hardy’s AV installations (contrasting obsolete tech with birdsong and rural sounds; raving heightens the senses, with or without additional stimulants—and clubbing takes you into industrial spaces but also brings you closer to nature).

As I’ve previously written in Elephant, I started working with Swindells at Time Out magazine (where he was Nightlife Editor for many years) when I was a teenager, so his photography and writing has a connection to many of my own clubbing adventures; his images here (including a 1988 shot of The Trip after-party, where clubbers literally spilled onto central London streets to continue raving) predate my personal experience, but they are unmistakably resonant, with a timeless sense of exhilaration.

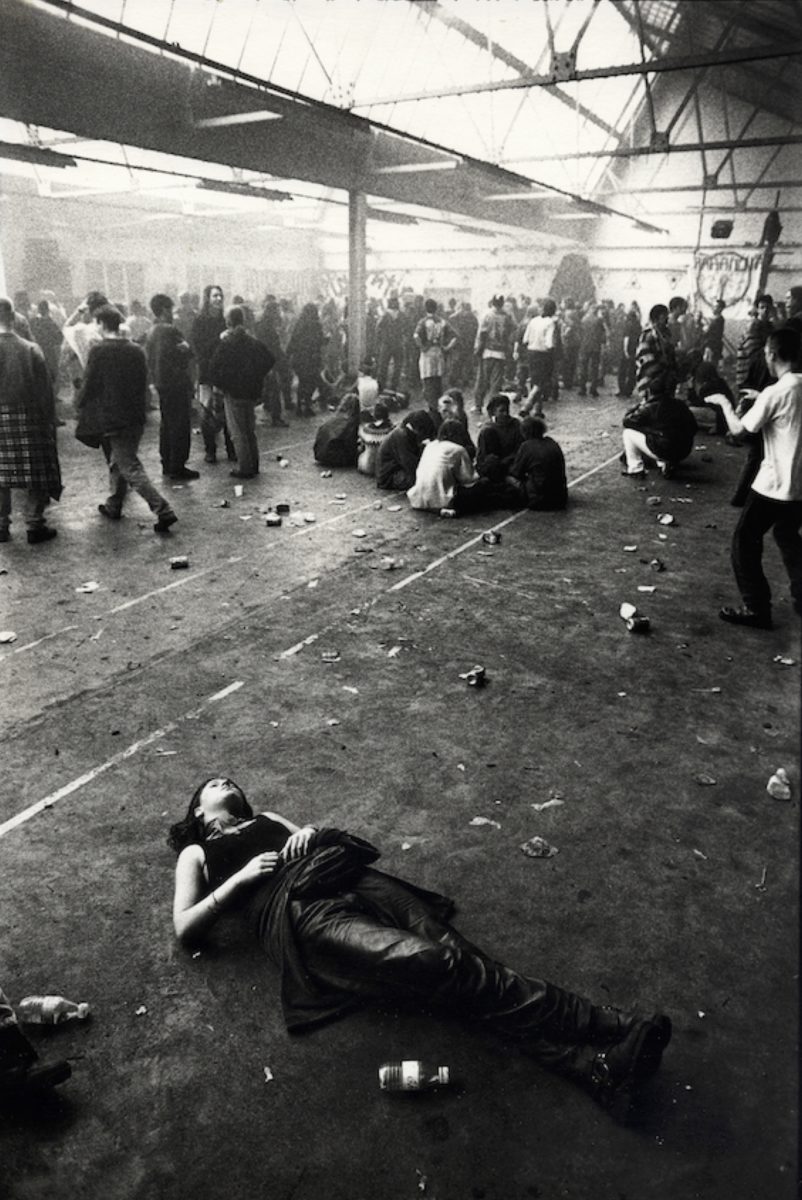

- Left and right: Courtesy Derek Ridgers

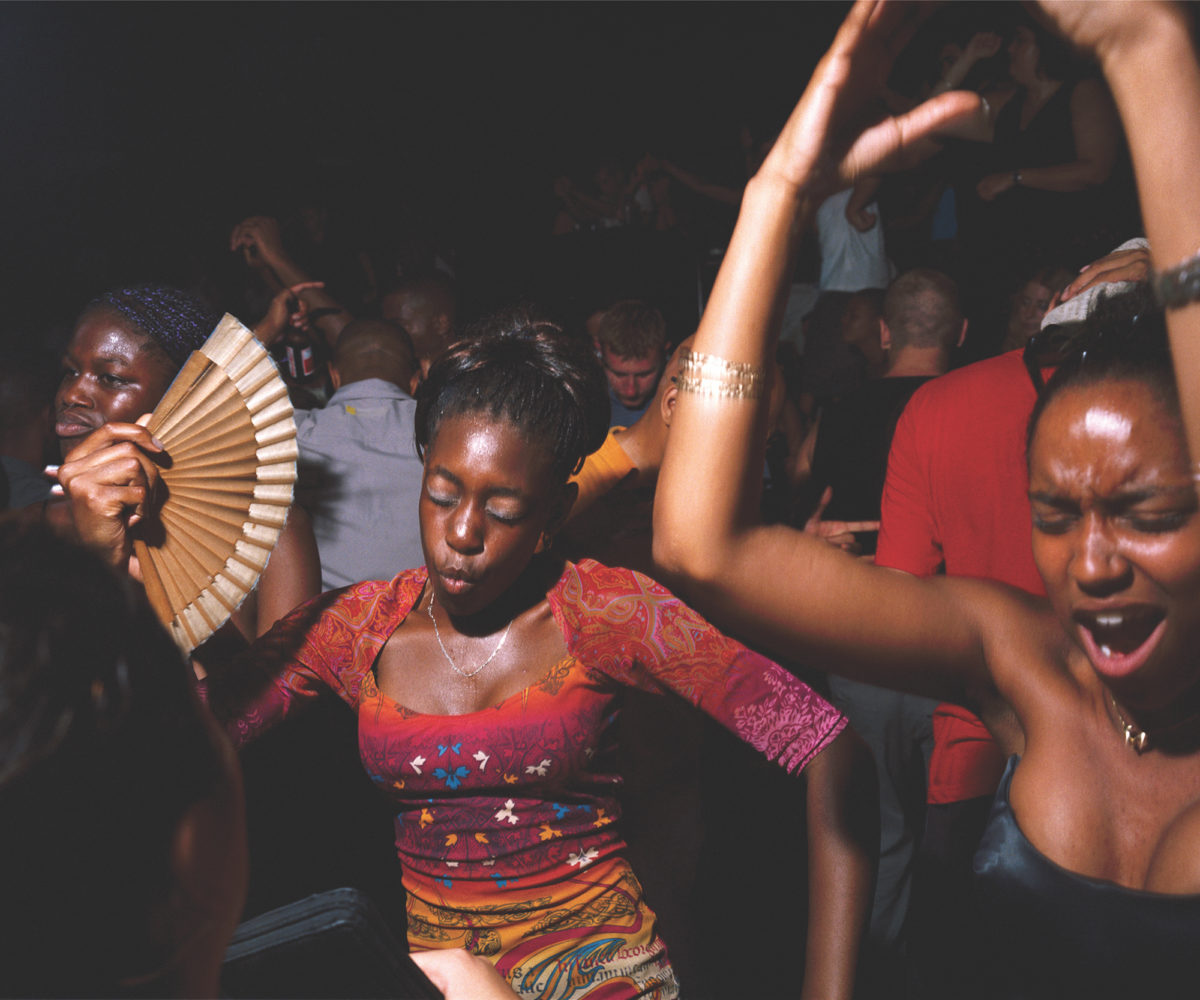

Photography is a strong strand of Sweet Harmony, with Swindells and fellow club-culture and magazine stalwarts Derek Ridgers and Ewen Spencer shooting from the thick of the dancefloor—you can practically feel the heat rising from these images. Qatar-born Molly Macindoe portrays the impact of rave culture beyond Europe, to the Middle East. There’s a deliberate informality to the presentation—large unframed prints are tacked to the walls, and additional notes are scrawled in ink—but still a serious intent to the collection.

“Raving heightens the senses, with or without additional stimulants—and clubbing takes you into industrial spaces but also brings you closer to nature”

A wall plastered with club flyers, portentous slogans and mixtapes triggers another head rush of nostalgia (“There comes a time in everyone’s life when status means nothing” declares the artwork for The Gathering: meeting point: London Bridge Station taxi rank). Rave culture’s mash-up of new sounds, sensations and youthful possibilities summoned this sense that staying up all night really could change your life; it had multi-dimensional vision, and love and peace in place of the belligerence that seemed to define punk (as a teen and twentysomething, I viewed punk with a certain distrust, which melted away as I grew older and made broader connections).

Conceptual depictions of rave culture—rather than straight-up shots—don’t always strike a convincing chord. Conrad Shawcross & Mylo create a ceiling-mounted spinning Lotus car installation that seizes attention (and Instagram feeds) without really saying anything; although Mylo has composed special music for the piece, only a persistently whiny motor sound was detectable on my visit. Transmission, an immersive multi-channel installation by DJ/producer/audio-visual artist collective Lost Souls Of Saturn is much more persuasive, although it’s still tricky for an artwork to generate quite the level of heart-thumping, bass-bumping intensity as an actual turn on the dancefloor.

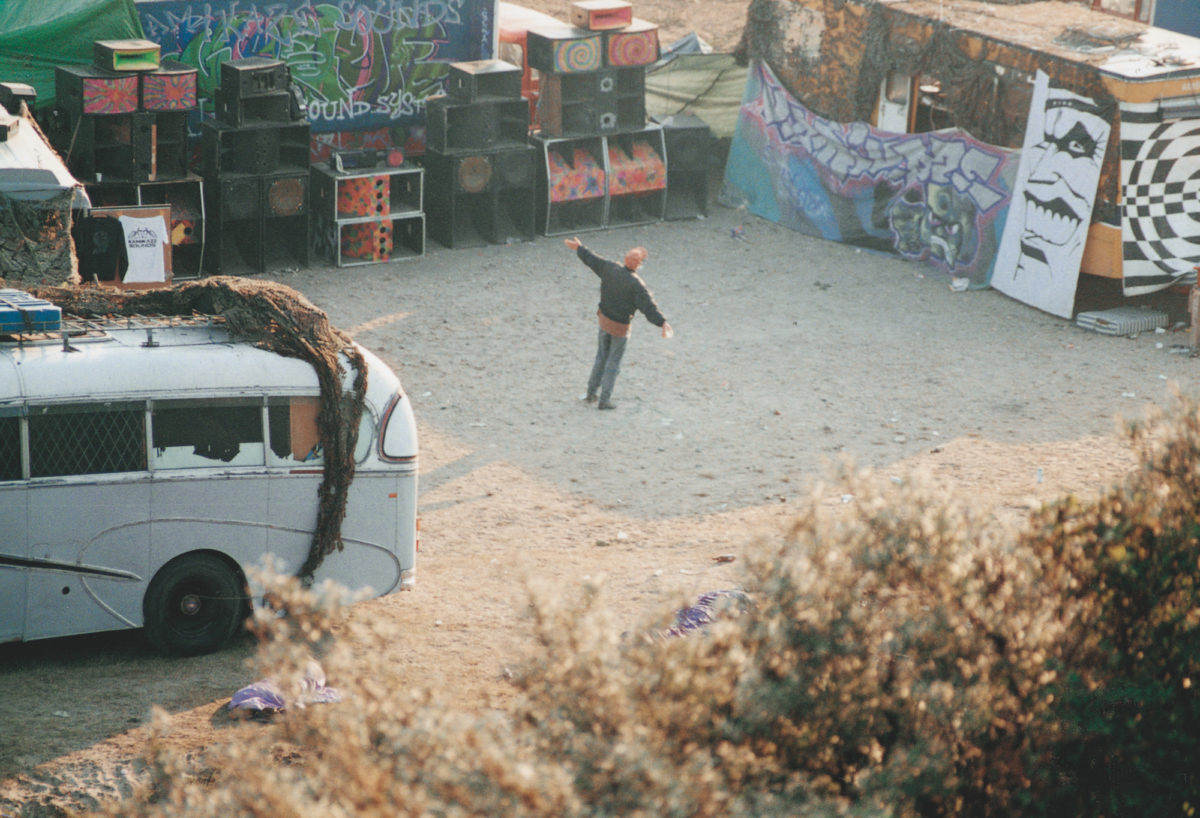

In contrast, Vinca Petersen’s deeply personal snapshots and insights (and a well-travelled bouncy castle, which Petersen transported across West Africa, and later Romania, as a form of “Laughter Aid”) form a memorable highlight. An entire wall is given over to Petersen’s scrapbook-style A Life Of Subversive Joy (2019), comprising her family photos, magazine clippings, club flyers and journal snippets: memories of fantastic lost nights, years spent in squat communities and on the road, caring for an ailing father and raising a young son. It is a moving testimony to rave as counter-cultural and positively empathetic, and it feels like a life passionately well-lived.

Courtesy Vinca Peterson

Sweet Harmony unites the personal with the political, and Adrian Fisk’s photos and footage of different eras of British protest—from the nineties Criminal Justice Bill to 2019’s Extinction Rebellion (which was soundtracked by various DJ sound systems) adds another contemporary perspective to rave culture. The past and the present also happily merge through vinyl racks and Spotify playlists, allowing visitors to explore musical offshoots of rave, as well as hands-on electronic dance tech.

“Rave culture’s mash-up of new sounds, sensations and youthful possibilities summoned this sense that staying up all night really could change your life”

As rave and club culture is crystallized as history, it often also becomes curiously subverted. Earlier this year, I attended an exhibition called Kings X Club Land, organized by the excellent youth arts collective Small Green Shoots; its clubbing retrospective (presented through the perspective of a much younger generation) felt like an alternate reality: almost like a Victorian vision of the future. Perhaps, as raving is essentially a hyperreal experience (with or without drugs), these alternate realities are now part of the trip—provided the emotional kick feels “authentic”. Sweet Harmony is similarly pitched at a multi-generational audience; I watched a school group trawl around the gallery (and wondered if they felt they were scanning ancient rituals), and I overheard a sixty-something American couple discuss how well-researched the exhibition was, as they perused the gift shop (Dan David’s limestone disco biscuits, £100).

Courtesy Adrian Fisk

And all the time, a multitude of sensations whirled through my mind: hollering with joy (and pounding the walls) when the DJ dropped a classic track; eyelash-tingling frequencies; the utter romance of a sunset or sunrise; a sense of affinity with strangers anywhere—a basement in Brixton; a techno hotbed in Berlin; a converted monastery in Lisbon; a boardwalk on Coney Island; a shed on the outskirts of Hull. I was never a cool kid, but something irresistibly brings me back to the rave.