How do you redesign a cultural icon? It’s a question illustrator Noma Bar

How do you redesign a cultural icon? It’s a question illustrator Noma Bar

was tasked with when conceiving the book jacket for The Testaments, Margaret Atwood’s long-awaited sequel to her astounding 1985 novel, The Handmaid’s Tale

. For many readers, the chilling image of women dressed in red cloaks and white bonnets—a symbol of their enslavement defined by a perpetual cycle of rape and childbearing—was already etched on our brains, but the essential image has recently become a shorthand for female oppression. This is thanks to HBO’s hugely popular TV adaptation, and swathes of protesters who have since donned the costume to demonstrate against archaic policies concerning reproductive rights.

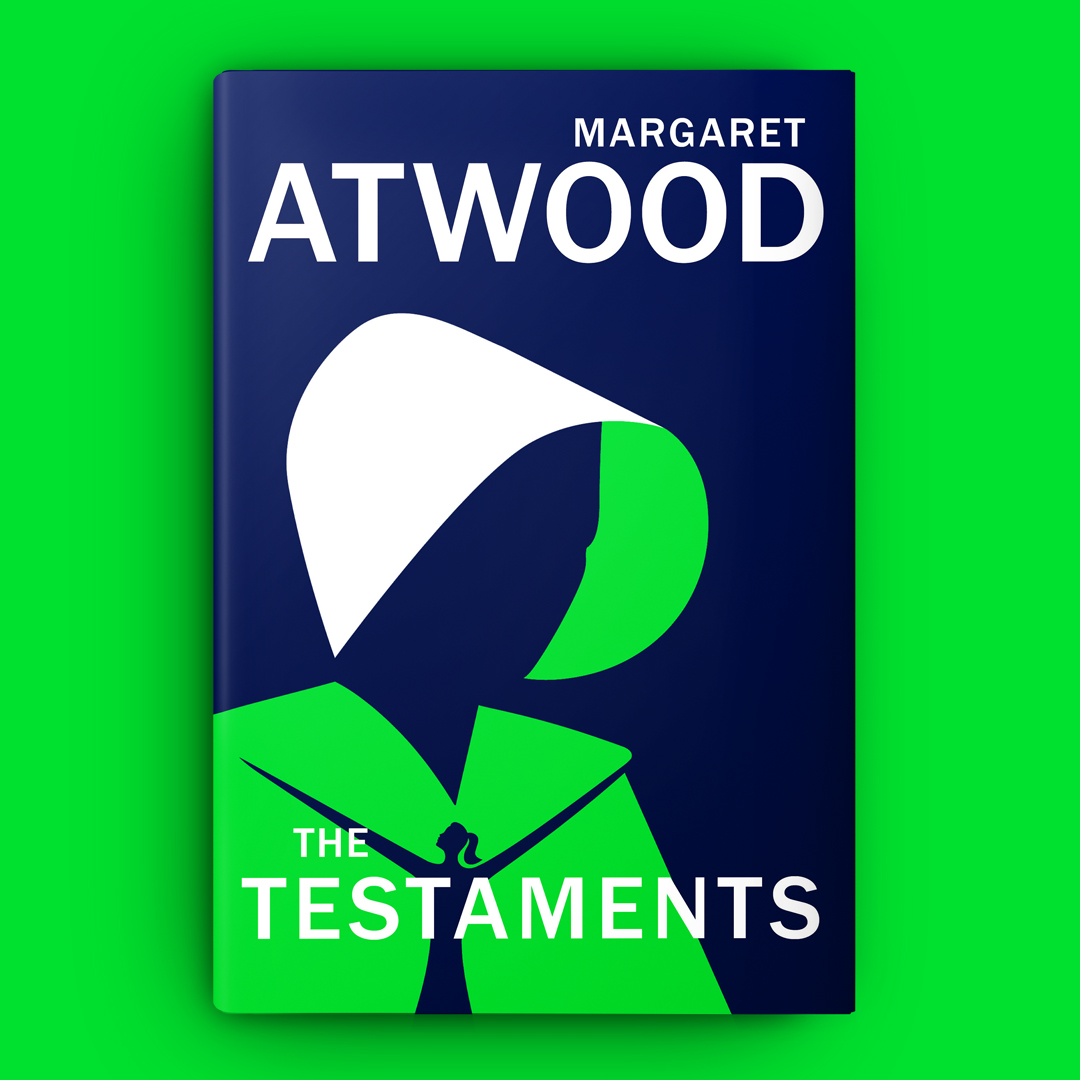

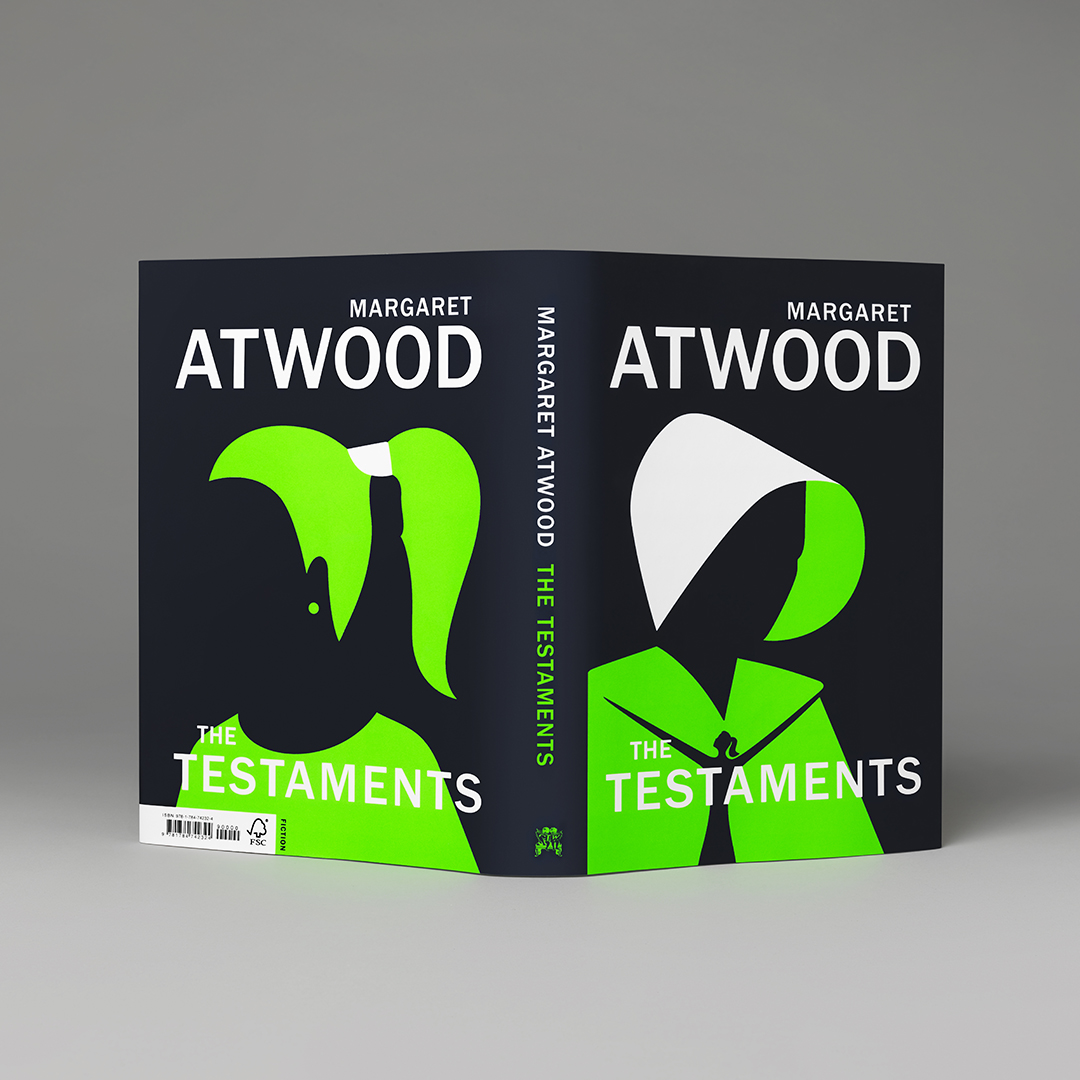

Bar is used to distilling visual signifiers to their utter core, and his exceptional dual images, which include incisive portraiture and political commentary, have graced publications from The Observer to The Economist—not to mention a recent edition of the Handmaid’s Tale. For The Testaments cover, a woman’s face is defined only as a negative imprint, and while the image of a bonnet and cloak is a given, the minor figure of a girl pleading with outstretched arms doubles as garment folds, as if she is rendered invisible. On the back, a more familiar emblem is formed by a similarly anonymous woman, this time with a ponytail and earring—an image of comparative freedom.

“Bar is used to distilling visual signifiers to their utter core, and his exceptional dual images include incisive portraiture and political commentary”

While Bar has maintained the visual shorthand of the handmaid, he made a striking choice with a lack of red, the colour that defines their costumes, not to mention blood, violence, lust and anger. By replacing it with an acid green he points to another central concern in Atwood’s novels: apocalyptic ecological collapse. This neon hue alludes to the toxic dumping grounds of Gilead, where prisoners are sent to toil and die, as well as the “high alert” symbolism of our own world, seen in hi-vis police jackets and the graphic identity of Extinction Rebellion.

The choice of palette and dual portraits also speaks to the defining principle that separates The Testaments from its predecessor. It focuses not on the singular account of the handmaid Offred, but three distinct female voices, which weave together to create a macabre tapestry of life within and beyond the borders of Gilead. As readers, we are charged not with identifying ourselves as handmaids, but with other women who are forced to endure or inflict inconceivable cruelty in order to survive. Bar’s faceless figures, which are fused as one in the book’s end papers like some kind of ominous emblem, point to this upsetting and brutal truth—in Atwood’s dystopia no one’s hands are clean.