Going “off grid” is something plenty of us might fantasize about, but few have the means or commitment to actually maintain. In our hyperconnected world, the majority of us are glued to screens that relay multiple forms of communication on a daily basis, and even more rural settings tend to be linked to mainline electricity or other forms of energy that make modern living possible. More often than not, the term simply means turning off your WhatsApp notifications and heading to a beach—but not so with Thames & Hudson’s new publication Off the Grid: Houses for Escape.

This hefty book takes a look at architecturally stunning buildings rooted in remote locations, with little or no connection to the outside world. The two-fold mission of seclusion and sustainability takes the form of houses constructed from everything from reclaimed wood to lava, nestled in heat-retaining rocks or exposed to the elements of land and sea.

These homes range from fully-fledged sites with guest rooms and expansive kitchens and swimming pools, to minuscule dwellings designed for limited stays. The former, nearly all of which are designated “second homes”, are still enough to make the average person salivate. Take the Granja Experimental Alnardo, in Valladolid, Castilla y León in Spain. The winemaker Peter Sisseck commissioned Henning Larsen Architects to create this “organic farmstead for the twenty-first century” which reflected his passion for sustainable and biodynamic forms of production. The luxurious property sits nestled in the hillside with commanding views of the countryside and is completely self-sufficient.

While Granja Experimental Alnardo is probably best described as an environmentally conscious family house, there are plenty of other examples that take simple living to the extreme. For example, the Watershed, designed by Float Architectural Research and Design, is little more than a shelter built as an escapist retreat, approximately twenty minutes’ drive from the town of Wren in Western Oregon. This structure holds all of the romanticism of a creative refuge, with a roof made from polycarbonate that allows you to hear the rain falling from above, and ecologically conscious additions that attract wildlife. What’s more, the site is designed to be removed and recycled, leaving absolutely no long-lasting impact on the land.

“The idea of a retractable roof is particularly relevant to Wales, the country with the highest percentage of ‘international dark sky”

These minute structures are arguably the most intriguing, in as much as wanting to know how and why their owners came to love their particular chosen location, as well as the innovative design processes that brought them into being. The SkyHut, found across various locations in Wales, is “designed to provide a unique place to experience the Welsh sky, with doors and roof that open fully to transform the hut into a glamping observatory”, says Phil Waind of Waind Gohil + Potter Architects. “The idea of a retractable roof is particularly relevant to Wales, the country with the highest percentage of ‘international dark sky,’” meaning it is relatively free from artificial light interference.

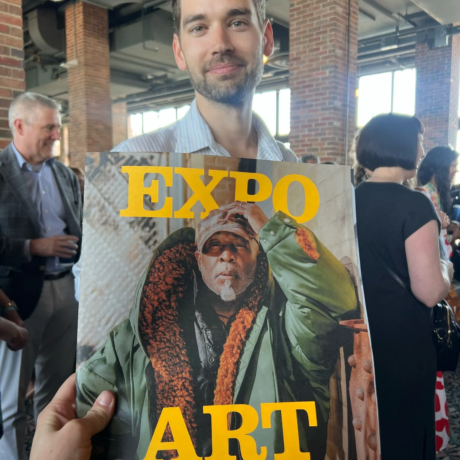

Saunders Architecture: Bridge Studio, Deep Bay, Fogo Island, Newfoundland, Canada. Photograph © 2019 Bent René Synnevåg

The key here is a desire to be as close to nature as possible, while still enjoying some seriously stylish architecture and interiors. The 72H Cabin, designed by JeanArch, is one of the most compelling. This relatively traditional-looking structure resides by the water on the Swedish island of Henriksholm where architect Jeanna Berger spent much of her childhood. However this unassuming shed on stilts, which holds nothing more than a double bed within, is sliced open on two sides by glass panes that extend across the roof, framing the forest, water and sky beyond. It is more akin to a sculptural installation than a dwelling.

Saunders Architecture: Bridge Studio, Deep Bay, Fogo Island, Newfoundland, Canada. Photograph © 2019 Bent René Synnevåg

The same could be said for the Bridge Studio, an artist retreat on Fogo Island

in Canada. Described as a one of six “apostrophes on the landscape”, it was designed by Todd Saunders to respond directly to its relatively harsh surroundings, appearing both highly sculptural in its elevated position beside the water, and also evoking the bay’s historical function as a point of departure for fishermen. The site of this small box among the brutal and devastatingly beautiful landscape puts one in mind of a post-apocalyptic refuge—albeit a very stylish one.

As well as gorgeously slick architectural photographs that document these structures, the human stories behind them tell a multitude of anecdotes that have led people to a lust for the quieter life. More often than not these are successful creatives, business owners and even architects looking to fulfil their pet projects—this is not a book about sustainable living that is accessible to the masses. The writing is nevertheless compelling, and the inclusion of an “off grid guide” for dummies as well as an appendix of architectural plans should be enough to satiate those with geekier tendencies. All in all, this is a book about escapism, which we can vicariously enjoy via the printed page.