diazotype prints from Francesca Woodman’s Caryatid series (1980) at the National Portrait Gallery. Photo © David Parry

Like dreams, angels exist in limbo: between the corporeal and the spiritual, the earthly and the divine. Photography exists in a similar realm, acting as both a record and a window to something beyond. Through portraiture, in particular, the human subject is elevated to a metaphysical realm; perhaps this is the closest we come to representing the angelic. In the work of Julia Margaret Cameron and Francesca Woodman, the portrait is a transcendental container, both rooted in reality and exceeding it. ‘Portraits to Dream In’, a dual exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery which combines the practices of these two women, is a glimpse into the outputs of overlooked female photographers. It is also a rumination on the angelic in art, but falls slightly short of capturing its nuance. ‘To dream beyond’ might be more suited as a title since both Cameron and Woodman’s work exists outside of boundaries: those of the human figure and the frame.

I’ve loved Woodman’s work, in particular, for a long time. Having only ever seen her prints from afar (through a screen), I approached ‘Portraits to Dream In’ with some trepidation– it seemed like an odd choice to pair her with Cameron, but I was interested and hoped it wouldn’t change my feelings towards her photographs. To me, they have always represented an impassioned relationship between the bodily and the spiritual. Despite varying links to femininity, sexuality and mythology, they also resist clear definitions, making them forever intriguing. Though Woodman’s subject was predominantly her own figure, I have always felt as if the intensely carnal nature of her photographs transcends physical beauty, becoming something more fluid and unreachable, like the passage of time and its inextricability from the body.

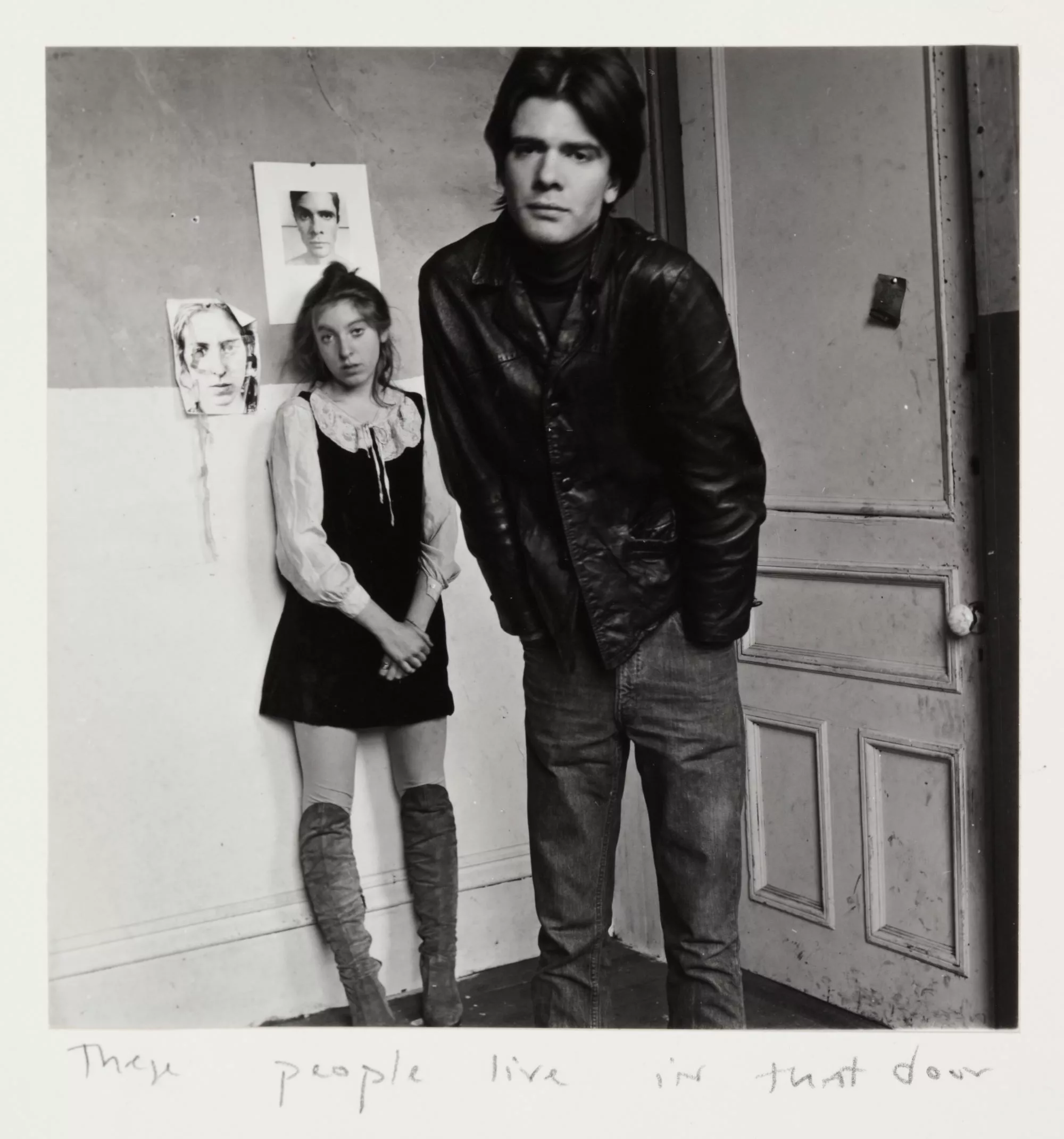

Meditations on time pervade the exhibition and, in doing so, provoke questions of the ways in which the temporal interacts with the body, art, and narrative. Cameron and Woodman were born over a century apart, the former taking up photography during the final 15 years of her long life and the latter working until the age of 22 when her life was terribly cut short. Consequently, Woodman is an eternal image of youth; her premature death froze her in time as a troubled heroine onto which the aspirations of many could be projected. Beauty and tragedy have always been irresistible, particularly when combined, and Woodman has often been associated with, as the art historian Carol Armstrong notes, “the Ophelia syndrome” of female madness. Accordingly, the exhibition’s curatorial team has made it a priority not to preoccupy itself with either artist’s biography. Instead, the show includes various journals and contact sheets which provide glimpses into Woodman’s creative process.

The nature of vintage prints, of which more than 160 make up ‘Portraits to Dream In’, also implicates itself in the passage of time. Though I’ve long abided by the gospel that art must be seen by the naked eye, I’ve never quite appreciated this in the same sense with regard to photography until now. The physicality of the photographs on show provides them with a tactile quality that is unable to be translated entirely into digital reproductions. Process becomes entwined with subject: as Cameron worked laboriously with the aforementioned glass plate negatives, Woodman hand-printed her silver gelatin prints in a darkroom. Photographs are sometimes mottled or overexposed; never technically perfect, but always personal. They are love letters to the technical and formal qualities of analogue photography, in which lost focus becomes an ethereal glow.

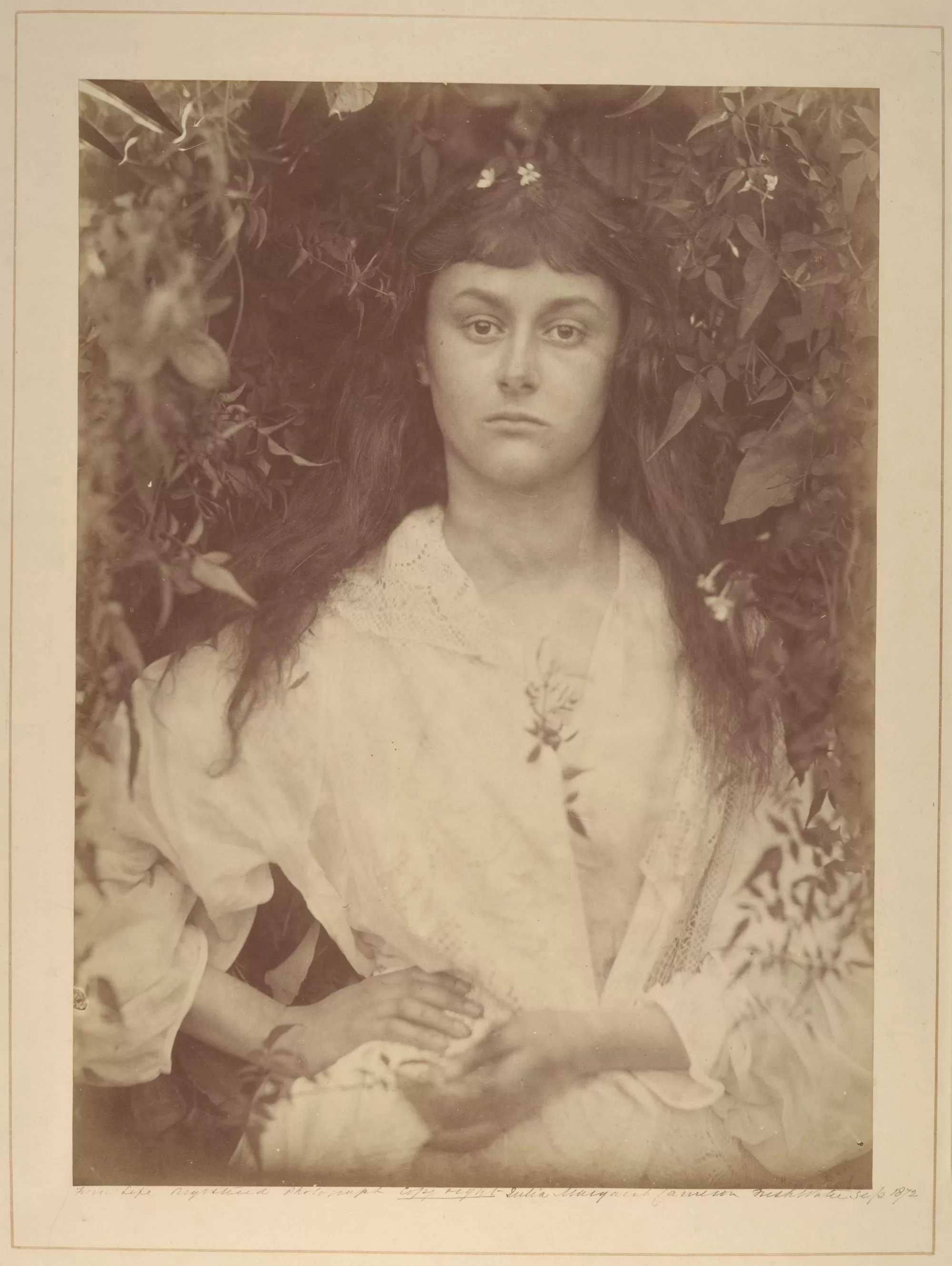

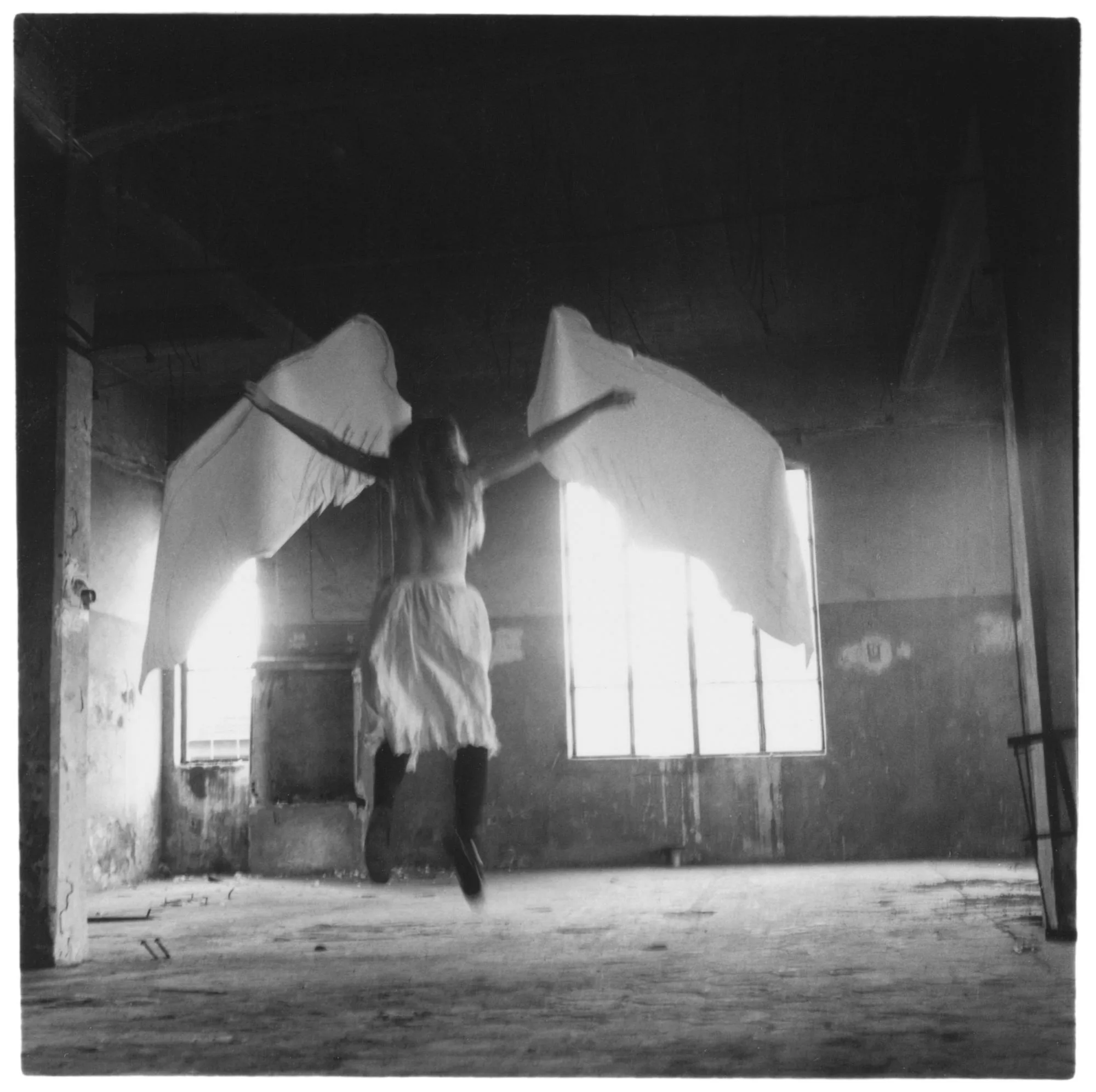

As its title belies, the ethereal and mystical is another fixation of the exhibition and one in which both similarities and vast differences between the artists’ practices are found. In Cameron’s vision of Daphne (as embodied by Mary Pinnock), transformed, according to Greek myth, into a laurel tree by her father to thwart the god Apollo, the nymph remains in human form. Woodman’s impression is more elusive, consisting of a series of self-portraits in which she becomes at one with the trees, dancing amongst them or wrapping herself in their bark. To Woodman, angels are similarly visceral beings; abstracted manifestations of light and movement which eschew symbolism. On Being an Angel (1977) depicts the photographer staring determinedly upwards towards the camera, her naked silhouette arched and straining away from the boundaries of the photograph as if attempting to dismantle the fourth wall. She is also a body becoming her environment– like much of her work, it is a reminder of the ephemerality of life and the fluidity of bodies against their fixed surroundings. In contrast, Cameron’s portrayals of the angelic are classical and distinctly Victorian: I Wait (Rachel Gurney) (1872), shows a child as putti, swan’s wings enclosing them. Though both women were fascinated by the angel as an amalgamation of the human form and spiritual transcendence, the cupid’s direct stare has a unique finality to it, unlike any of Woodman’s figures.

Art, after all, is a possibility rather than a definition. This is probably what the show’s team aimed for when placing the work of both photographers together, and in some way, it provokes dialogue, with their union acting as a prompt to consider their work in new ways. Sometimes, however, in categorising links between works, the approach feels slightly reductive. By placing various of Woodman’s more immediate, ephemeral images next to Cameron’s carefully considered (and physically larger) portraits, they are stripped of space to breathe. The only time Woodman’s work psychically takes centre-stage is through her ‘Caryatid’ series (1980), a striking example of formal consideration, printed at a monumental scale using diazo type printing during the last year of her life. The technique, which involves the use of compounds which are sensitive to blue and ultraviolet light, has rendered each print in dreamlike violet shades. They depict the artist herself posed as the carved female figures which adorn the columns of ancient Greek temples. Larger than life-size, Woodman’s pillars are less imposing than they are symbols of strength or a ‘performance’ of classical depictions of the female form.

Cameron’s renowned portraits of famous Victorian men are also diminished by the pairing. Those which are present in the show, such as The Astronomer (Sir John Frederick William Herschel, 1867) and Iago – Study from an Italian (1867) are amongst the most haunting and complex works on display. Unfortunately, many of Cameron’s depictions of women are limited by their prim Victorian sensibilities and representations of female beauty. Sadness (1864) shows the renowned 19th century Shakespearean actress, Ellen Terry, leaning in melancholy against a patterned wallpaper. It is an image of beauty and muteness; a pre-Raphaelite foretelling of The Virgin Suicides. Placed next to Woodman’s Polka Dots #5 (1976), in which the photographer contorts her dotted dress-clad body before a bare, decrepit wall, Sadness seems oppressive and idealised. Its subject is trapped, made claustrophobic by the femininity projected onto her. In this sense, it is distinctly rooted in its surroundings, inextricable from its environment.

This is where the show’s determinedness to remove biography is its major fault. Cameron and Woodman’s art was never purely about ‘dreaming’, or escapism (as the show’s title may lead you to believe); rather, it is simultaneously entwined with the complexities of reality. Since the works on display are so shaped by time, it makes little sense to disregard circumstances surrounding both photographers’ output: circumstances shaped by misogyny, yes, but also enabled by notable privilege. Most of the female bodies on display are white, slim, and conventionally attractive by Western standards. Cameron’s photographs are of Britain as the product of the Empire, and her own family was involved in British colonial India. Woodman’s artist parents encouraged her to take pictures at a young age. Their transcendent physical forms are forms of the few.

Both artists were talented in their own ways, and despite the limitations enacted upon them, they produced bodies of work that deserve– as the show acknowledges– to be assessed as art in an equal manner to their male contemporaries. I am struck by both photographers’ ability to tell stories in singular images– often solely using the figure, with nature or spartan surroundings as the only props. The body tells the story, after all, implicating itself in both environment and history. Still, despite intentions to enhance the other’s work by placing them side by side, the pairing is somewhat tenuous. Both deserve their own exhibition, which would allow their art to be truly and fully recognised and enjoyed.

Written by Ella Slater