Elisabetta Catalano, Bolkan Florinda, 1969

© Archivio Elisabetta Catalano

“Just because you are young and blonde, with boobs out to here, doesn’t mean you can’t be intelligent,” Paola Ugolini assures me, as we walk around the inaugural exhibition she has curated at Richard Saltoun’s new gallery in Mayfair, titled Women Look At Women. “Richard wanted to show all of the female artists he had, but I said ‘no’. This is a show specifically about women looking at themselves and other women through the camera lens and challenging what we see because women are always being categorized.”

Ugolini has brought together some of the best-known and most influential artists from the field of feminist photography, including Jo Spence, Francesca Woodman and VALIE EXPORT, but she has focussed on unseen, lesser-known works by these big names, as well as introducing a few that might not spark immediate recognition.

Renate Bertlmann, Verwandlungen (Transformations), 1969/2013 © the artist

In the case of Renate Bertlmann, a display of previously unprinted self-portraits taken in 1969 dominate the first wall of the gallery. These compelling, comical images show the artist embodying traditional “feminine” stereotypes with a range of props. The black and white photographs have the candid quality of a photo booth or, in more contemporary terms, the compulsive bursts of selfie-taking stored on our phones before the “final edit” makes it onto Instagram. “These photos were so ahead of their time,” says Ugolini, “but Renate didn’t even print them until 2013, when Richard discovered them in her studio, because she didn’t think they were important.”

This idea of art that deals with female identity being somehow lesser is something that remains pertinent today––just ask any woman who has been to art school––so it is reassuring to see an exhibition that moves beyond the reductive, catch-all interpretation of militancy in “feminist art” that practitioners from the sixties, seventies and eighties often fall victim to. One of the most enlightening inclusions comes in the guise of several glamorous images shot by Elisabetta Catalano, an internationally renowned Italian photographer known for her portraits as well as fashion editorial. “I wanted to show the strength of both her and her models,” says Ugolini, as we stand in front of a swathe of glamorous women with bouffant hair, languid poses and powerful gazes.

“Many of these women were beautiful, and used their sexuality in their work––there’s nothing wrong with that.”

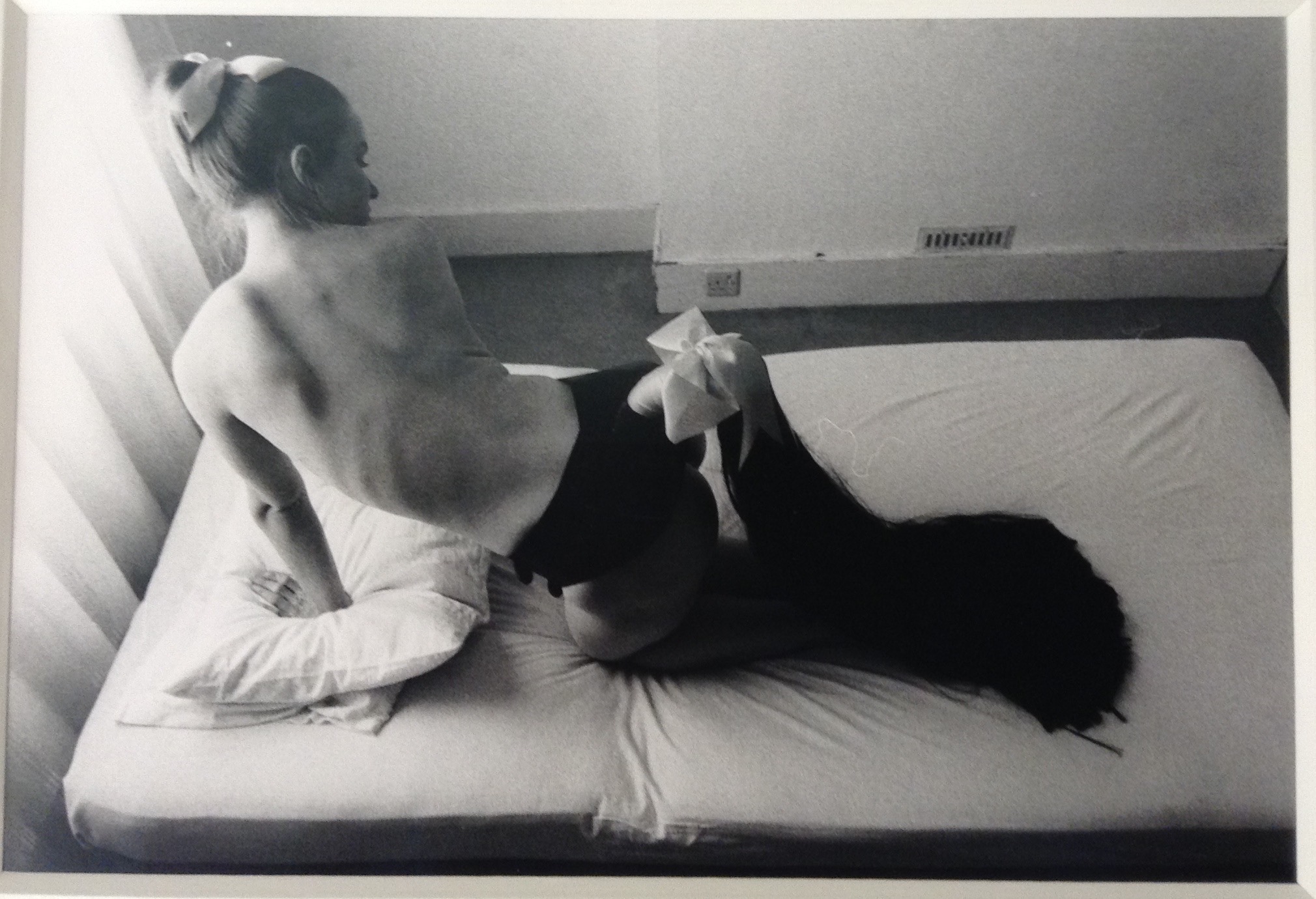

Celebrating sexuality was certainly something Ugolini didn’t want to shy away from in this show, and she has straddled the problematic path of presenting female agency that, at times, could be construed as playing into the male gaze. “Many of these women were beautiful, and used their sexuality in their work––there’s nothing wrong with that,” she says, with a celebratory gesture towards three photographs by Rose English, showing a young woman on top of a bed, wearing an enormous horse’s tail. With her hair perfectly tied and her ribs protruding through her narrow, bare back, there’s something suggestive about these poses, but also comfortingly subversive and surreal. It’s a great example of more obscure images that feed into an established practice, as English is celebrated for her performance and video works that obsess over equine movement.

© the artist

The only sculptural pieces in the show also engage with our assumptions over coded imagery. Helen Chadwick’s stark, geometric blocks immediately ally themselves with minimalism, which in turn draws “masculine” narratives. However, these objects have been printed with ghostly images of Chadwick’s body and household items, which add a softer, domestic layer onto these harsh forms. The result is both playful and knowing; she has married two distinctly gendered forms of art production into a cohesive whole.

In another playful interplay, Ugolini has used two existing alcoves in the front gallery space to create two “peep-shows”, where a single visitor can get up close to a full-colour image of Chadwick’s titled Ruin, or Friedl Kubelka’s Pin-up, directly opposite. Entering these tiny antechambers forces the viewer to engage with compelling but almost brutal images. Chadwick borrows from classical poses as she turns away from the viewer while presenting her naked body and clutching a skull, while Kubelka invites you to examine her contorted, stockinged figure within a mirrored room. She’s photographing herself, but she is pointing the camera directly at you.

More bodily contortions are found in Annegret Soltau’s experimental face wrapping. Her photo series documents the process of gradually winding thread around her head until she is unable to speak or properly move, before cutting the lines away again. According to Ugolini, Soltau would do this at parties, making her performance all the more frustrating as she attempted to communicate with friends. Her practice with embroidery materials later moved on to incorporate stitched together negatives that formed figures akin to Frankenstein’s monster, a process that was borne out of her anxiety at the prospect of becoming a mother

, and the negative impact that it could have on her career.

Helen Chadwick, Ruin, 1986. Installation View, Women Look At Women, Richard Saltoun Gallery

Soltau’s anxious aesthetic dismemberment places itself directly onto the body, and a similar thread of violence is shown in Alexis Hunter’s series Secretary Sees The World. These twenty hand-coloured images depict the point of view of a woman poised at a typewriter before she begins to fiddle with a small globe. As she tears the object apart her hands become cut and bloodied, in a frustrating and seemingly pointless act. This form of aggression alludes to the stifling professional confines many women endured during the seventies (and remain relatable today) and also hint at forms of mania that have often been aligned with female emotions.

“There is a new, bold ferocity that I have never seen before.”

One final highlight comes in the form of an enormous image of Francesca Woodman, her naked body stretched at a fierce diagonal and surrounded by debris, while a fur is wrapped tightly around her neck. The piece was printed posthumously in 1978, and it is a significant move from the diminutive way her photographs are usually presented. Ordinarily, they draw associations with ethereal daguerrotypes and intimate domestic settings, but in this metre-squared version there is a new, bold ferocity that I have never seen before, which is something of a marker of where the power of this exhibition lies.

In what is a relatively small show Ugolini has tackled the often lazily drawn associations between well-known works of art by a few, leading artists of the period. Such reductive vignettes distil a time of joyous, exciting and innovative art production into a flattened, homogenous group. Conversely, in this show the introduction of relatively unknown pieces and lesser-known artists presents a multi-layered realisation of how women dealt with female identity and the body at a time where it was deemed of little importance. It encourages us to move past our preconceptions and look again.

All images courtesy Richard Saltoun Gallery