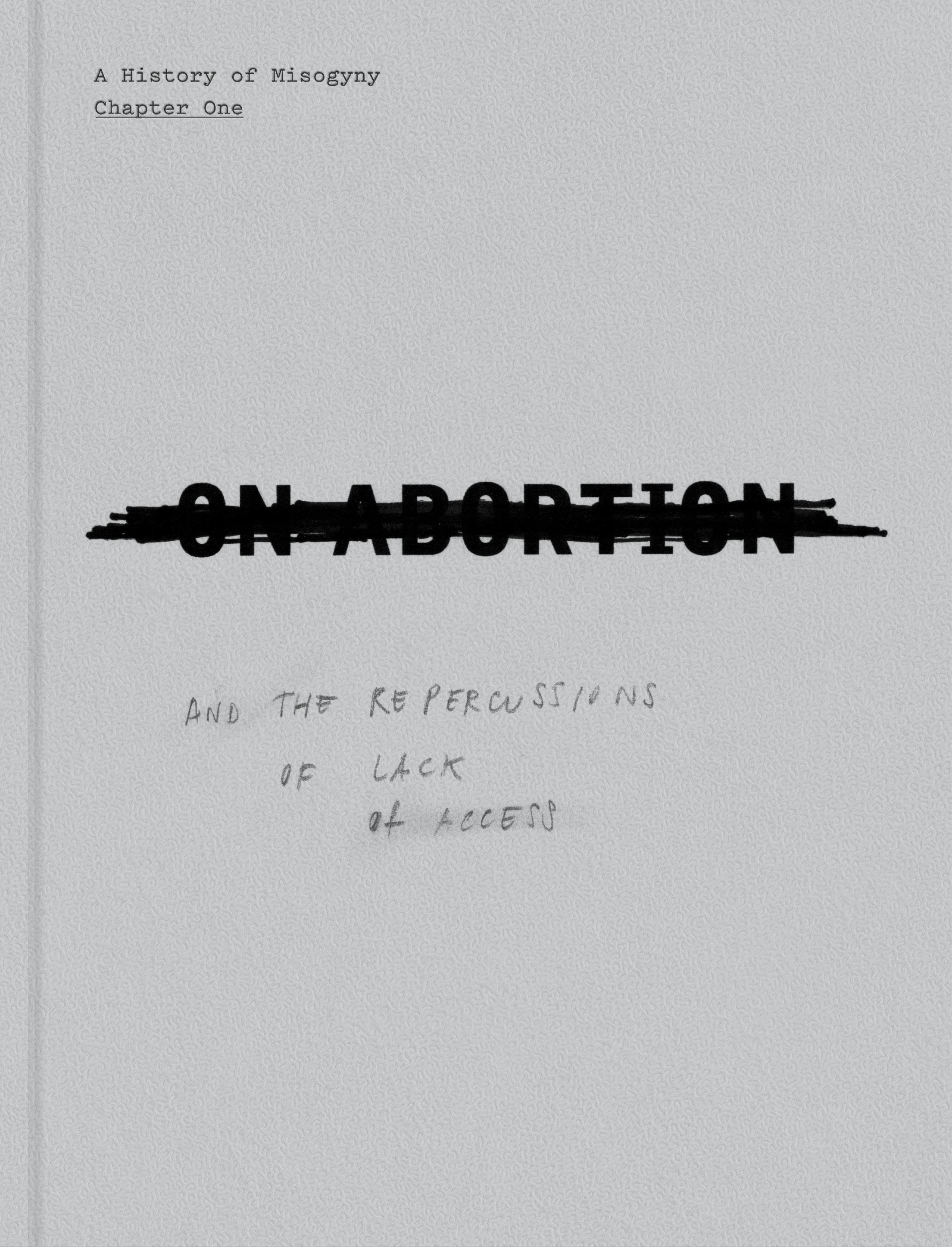

“I started to do abortions by chance, because I was once eating with a friend and she asked me: Do you want to come with me?” So recalls an anonymous text that introduces photographer Laia Abril’s book On Abortion—deep and often emotional research on abortion practices in the last century up to the present that includes direct, detailed accounts both from women who have performed and who have experienced abortions.

The publication forms the first part of Abril’s A History of Misogyny, On Abortion, which was exhibited at Les Rencontres de Arles in 2016, and it has already received recognition as a groundbreaking work, with awards and prizes. In contemporary art, very few artists have broached the subject of abortion so explicitly. Tracey Emin’s personal writings and works on abortion such as Terribly Wrong (1997) remain unique in the arch of art history, despite the fact that one in four women will have been through an abortion by the age of forty-five. To begin to talk and make art about abortion is not an easy task: it is a highly sensitive subject for those who have experienced it and one that ignites heated debate on both sides of the pro-choice/life debate. Perhaps because of this, Abril’s book sticks mostly to documentation, facts, photographs and medical science. Healing takes time. The first step is confronting the experiences of these women, and it is their voices that Abril emphasizes.

Yet the recognition only paves part of the way to bringing attention to a conflicted subject that has been kept quiet for centuries, often as absent from art as from political agendas. Approximately 30,000 women die every year from botched abortions; it is illegal in twenty-six countries, some of which have a criminal charge for women for choosing abortion under any circumstances, and some of which allow abortion in extreme cases, such as rape or a serious health threat to the mother. In many countries where abortion is technically legal—including the US—cultural and social pressure mean many women carry pregnancies against their will, or end up turning to methods that put their lives at risk.

“To begin to talk and make art about abortion is not an easy task”

This is the very real context that On Abortion is rooted in. It is clearly not only an artistic project, but a practical, rigorous history that conceptualizes the potential issues with the way we view abortion, with empathy for those who have, and continue, to experience it, and acknowledgement of the complexity of the conversation the world over. The book begins with the documentation of old contraceptive methods and illegal abortion tools, giving a graphic medical insight into the practices and pain of the process.

There is unflinching documentation of the politics and legislation around abortion, particularly in the US, where extremist anti-abortion groups such as The Lambs of Christ have incited and executed violence against family planning clinics and doctors. This is juxtaposed with threatening transcripts left on the voicemail of an abortion clinic in Florida, and detailed accounts of women who have been criminalized for attempting abortion, and the case of G.Y.I who suffered a forced abortion in China at eight months.

It is the stories of these individual women, however, that really stay with you after reading On Abortion. Their pain culminates in a clarion cry from Abril that cannot be ignored. What, she asks, are we saying if women are not given agency over their own bodies? When abortion is legal, and safe procedures are available, how can they be accessible, and how can those offering them ensure that women feel supported? Who should be responsible for overseeing and implementing the law around it?

On Abortion is essential reading but it is not easy to read. I found myself in tears over certain pages. A particularly difficult image is the police photograph of Gerri Santorini, a mother of two, lying dead on the floor of a motel room in 1964 aged twenty-eight after she and her partner tried to perform a self-instructed abortion. The image was subsequently used by the pro-choice movement in the US—also highlighting the complexity around interpretation.

Impossible to erase from your conscience once you’ve seen it, On Abortion is an urgent and vital testimony—and an explicit demand for visibility and open conversation.

Extended Captions

Portrait of Marta “On January 2, 2015, I traveled to Slovakia to have an abortion. [In Poland, abortion is illegal except in cases of sexual assault, serious fetal deformation, or threat to the mother’s life.] I was too scared to take DIY abortion pills alone. What if something went wrong? So I decided to get a surgical abortion in a clinic abroad. I felt upset about borrowing money for the procedure, and lonely and frustrated because I couldn’t tell anyone what was happening. The hardest part was facing my boyfriend, who opposes abortion. All the same, I felt stronger and more mature afterwards.”—Marta. Abortion is legal in nearly all EU countries, except Poland, Ireland and Malta. In Poland abortion is illegal except in cases of sexual assault, serious fetal deformation, or threat to the mother’s life. The official number of abortions performed in this country with 38 million inhabitants, is only about 750 per year. According to Dutch pro-choice organization Women on Waves, the real number is closer to 240,000. Marta’s portrait comes along a photonovel of her illegal abortion.

The Oral Solution The infusion of local plants ruda and chipilin are used by Salvadorean women to abort during the first trimester. To abort during the first trimester, some Salvadorian women prepare an infusion of local plants ruda and chipilin. It’s just another cocktail on an endless list of drugs and foods thought to induce miscarriage, including clover mixed with white wine, squirting cucumber, stinking iris, slippery elm, brewer’s yeast, melon, wild carrot, aloe, papaya, crushed ants, camel hair, lead, belladonna, quinine and pomegranate. Alternatively, self-starvation.

Portrait of Magdalena “It was December 17, 2014. I took a pregnancy test and it came out positive. I am gay—I don’t want to talk about how I got pregnant. I don’t know for sure if my grief for the abortion is over, if I left it all behind. I think about it once in a while, and sometimes I cry. Not much, though, and not because I regret it. I don’t. I know I made the right choice, and the only possible one. It was the hardest experience in my life. I am a different person now. And I’m proud of myself.”—Magdalena.