Orlando Estrada’s imaginative sculptures imagine new terrains beyond and because of the human-nature binary. At Rachel Uffner Gallery’s two-person exhibition Procession with Estrada and Shani Strand, the silhouette of horses offer new horizons to see his vision.

Soft light pours into Orlando Estrada’s home studio and glows across various trinkets. There are half-finished sculptures hanging on the wall, 3-D printed butterflies, microchips found on the street, a desk strewn with prints and flames, and a box of Cheerios with flame-shaped cut outs pinned to the wall. For all of the clutter in the artwork, the space itself is pristine (Estrada is a self-admitted clean freak). The artist who spends his time split between Brooklyn and Miami is a collector and always has been. “Things just kind of stick to me for some reason,” he says, like seashells, which have become part of his visual language after one found its way into an early work.

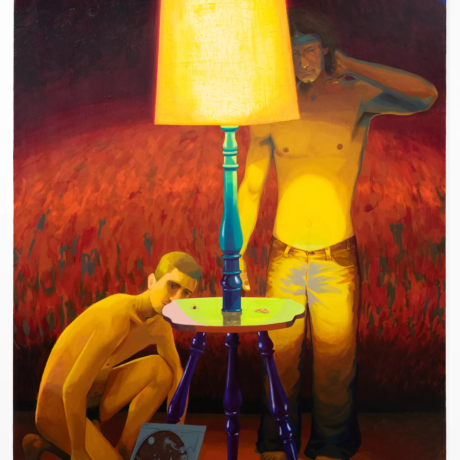

In his current two-person exhibition “Procession” with Shani Strand upstairs at Rachel Uffner Gallery. Small, ceramic figurines by Strand dance throughout, populating Estrada’s terrain.

In Coffin Dancer, 2024, a horse’s silhouette appears made of rusty steel or mossy dirt (it is actually foam coated in coconut fibre). Numbers from 1-100 were born from a story the artist’s mother would tell him from when she was a young child. “My mom was a middle child, and she always felt kind of ignored like in her family unit. And so one time she was at her grandmother’s house,” he recounts. “In Puerto Rico, they race these mechanical horses, and they used to announce it on the radio. My grandmother used to always bet on the horses, and my mom felt like my grandmother would always pay more attention to the numbers than to her. So in an act of rebellion, my mom took her power back. Over the radio, she started counting one, two, three to distract my grandmother, and my grandmother got so mad and chased her around the house while my mom just kept counting,” he laughs.

Elsewhere, The Bathhouse at the Naturally Flowing Hot Mineral Springs, 2024, features paper cut-outs of trees and flames, pearls, coconut fibre, seashells, plastic palm trees, and of course the aforementioned bathhouse resting on the horse’s back on stilts. “In Puerto Rico there’s traditional folk art called casitas, which are ceramic facades of little houses. That was my mom’s hobby for a while. I always grew up with them decorating the house, and that’s where the image of the house really stuck in my brain as like an art image,” says Estrada, adding that the domestic space got an added layer of meaning when he discovered gothic art. “I’m a Goth at heart,” he says with a smile.

In a sense one work’s title, The Unfathomable Spirit of the Natural World Adapting to Novel Circumstance, 2024, seems to say it all. A garden of manmade trinkets manifests: mini fake succulents and daisies, butterflies on wire pins, seashells, memory cards and computer chips, shoots of plastic grass, a miniature ceramic vase.

The Brooklyn-based artist was born in Orange County, California, spent his childhood on a coastal military base in Puerto Rico and his teenage years in Miami, and eventually was called to New York. Estrada grew up in military-base suburbia, in what he refers to as a”bizarre social experiment,” surrounded by nature and the colourful folklore-inspired costumes of various carnivals. As a child, he looked at the manmade structures and otherworldly rock formations with wonder. “There used to be giant red land crab migrations during the breeding season. The streets and the yards and everything would become flooded with red crabs all over the place. Driving the car, you would try to avoid them, but you would crunch them,” Estrada remembers “I remember that was my first experience with death,” he continues, “and understanding that there’s this massive amount of animals trying to survive and like every crunch you hear is the difference between like that animal surviving and that animal dying. It says something about human ambition, too. It’s not a question of whether people are going to drive.”

And art was everywhere, from the casitas (mini ceramic facades of homes) his mom made and decorated the house with to art classes that say a four-year-old Estrada mystified by decalcomania. As a teenager, he discovered the works of the Mexican-American sculptor Luis Jiménez, whose practice was ingrained with his life. “Then the first time I saw Félix González-Torres’ light bulbs, and that blew my mind,” says Estrada. “It was pretty Earth-moving.”

Estrada’s is a practice grounded in spiritually charged terrain. Constantly reaching for materials of today to describe the makeup of tomorrow, he eschews language for a lexicon of found, synthetic objects that both recall and contrast the natural world. His earlier works were more clearly a product of and a response to his Miami, specifically South Florida’s environmental issues. His recent works on view are less of a one-to-one.

“My work is not just about the environment,” he emphasises. “What I’m trying to do is actually just capture the moment, and obviously climate change is the moment but there’s a lot more to the work than just that.”

So in an attempt to create a world that expanded rather than contracted his holistic view of things, Estrada began to think about time, and then beyond it to prehistoric art. “I wanted to get away from a landscape that reads as simply a landscape,” he reflects. “I wanted it to read more like a mindscape.” Then the horse motif came to him in a dream. An emblem of mankind’s drive to conquer nature. It was by looking at cave paintings that the idea of the horse began to take shape as a horizon on which Estrada could build his world.

For the artist, the history of domestic horses means many things: transportation, warfare, economic development, colonisation. Yet, despite all the human development done on the back of these animals, horses also offer a throughline between humans and the natural world that goes back as far as cave paintings.

Humans will never stop trying to control land, yet, Estrada’s work seems to suggest nature will find its way. Before he turned his focus to his mindscapes, he was brewing kombucha to make works he describes as much more relational. Then he zeroed in on geological core samples and created what he describes as “imaginary cross-sections of the Earth’s crust… what it would look like if there was this fossil layer with dinosaur bones, and then when you get to what they call the Anthropocene era, there would be plastic bubblegum wrappers and all this shit embedded in it, too.”

The inability to imagine far into the future is the crux of humanity’s issues. As fantastical as Estrada’s vision of fossilised relics of today might seem, or even look on his terrains, it is very much the fate that we are hurtling towards. Yet, the idea of finite resources is the antithesis of capitalism, and therefore, it remains unfathomable within the framework that we live in.

Estrada’s work is an effort to collapse time, or at least reframe it. “Human time is really short, a day is 24 hours, but in geologic time like a million years is like nothing for like stones,” muses. The artist embraces post-human, pre-human, non-human ways to think about our fleeting mark on Earth. The latter is an extension of his deep interest in the teachings of Shamanism, its energy work and emphasis on ancestral healing.

If you trace your ancestry far enough back, eventually human forms beget more rudimentary shapes, like amoebae, Estrada tells me. His eyes light up as he imagines “some kind of snake-like thing that crawled out of water” some 750 million years ago. It can get whimsical really quick, he laughs. “But I want to believe that a lot of people think about these things, too. I hope that this work that I’m making helps—not to resolve anything because I don’t think I don’t think art really has the ability to resolve anything—but at least we can contend with these thoughts in a productive way.

Written by Meka Boyle