In Cara Benedetto’s current exhibition at Rose Easton (London), the artist explores the performance of white female victimhood. Ella Slater explores the context of this exhibition and examines Philippa Snow’s accompanying text.

Photo by Jack Elliot Edwards

In 2019, British Prime Minister Theresa May stood outside the door of 10 Downing Street and made her resignation speech. Towards the end, as she pronounced the words “the country I love”, her voice wavered and cracked, and she strode quickly away from the cameras. In the aftermath, various public figures and journalists insisted that, despite her lack of humanity as a politician, her breakdown into tears meant that it was impossible not to feel sorry for her as a person. No matter her ideological cruelty to the most vulnerable people in the ‘country she loved’, her flaunting of the “hostile environment” she had created for immigrants and their subsequent dehumanisation. May’s display of emotion afforded her the acknowledgement of humanity, which she never allowed those she had the power to help. It was– as the artist Cara Benedetto might say– a performance of emotion: the white woman’s tears as a strategic device.

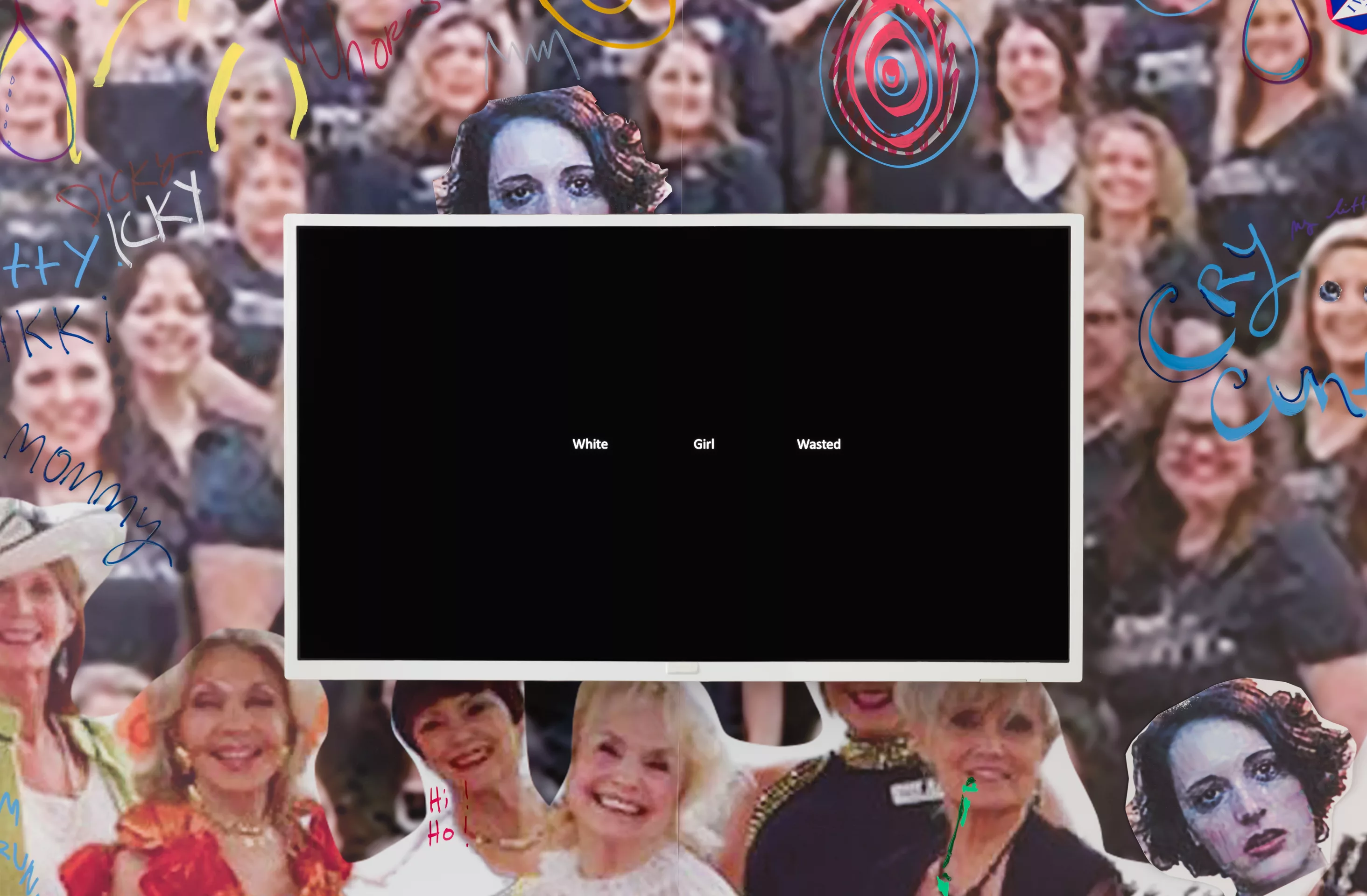

At Rose Easton gallery, Benedetto’s solo exhibition is titled ‘WGW, or ‘White Girl Wasted’. It is a term which– according to Urban Dictionary, means “to be extremely drunk, high or a mixture of both. The term is derived from the extreme inebriation most commonly experienced by white females between age 17 to 27.” The addition of ‘white’ is significant here: it is this which afforded May her loss of control, her capacity to cry. Though the ex-PM and ‘wasted’ might seem unlikely companions, like her display of emotion, the performance of a messy, helpless white woman is weaponised time and time again. Both Benedetto’s research and art practice investigates these assertions of white female victimhood and the implications they have on both racial capitalism and heteropatriarchy.

The centrepiece of ‘WGW’ is a monumental wall vinyl, titled Moms 4 Liberty, United Daughters of the Confederacy and Royal family at the Queens Jubby Book Banning Birthday Parteeeeeeeee (2024). The majority of the collage is taken upby a pixelated group photo of the aforementioned ‘Moms for Liberty’, a conservative political association who advocatefor censorship of education involving LGBT rights, as well as race and ethnicity. Before them stand the United Daughters of the Confederacy, complete with lurid ballgowns. The United Daughters, whose headquarters are in Richmond, Virginia, where Benedetto lives and teaches, are an American hereditary association, famous in part for their support of Confederate monuments and statues with roots in slavery and oppression. Benedetto, like an incensed teenager to a school photograph, has mutilated their faces and bodies, as well as others on the wall, with puffy paint and masks of the quintessential ‘forgivable white mess’: Fleabag. There is something comic and childlike about this vandalised photo collage, but beneath its witty remarks and rainbow-coloured doodles lies the spectre of violence.

In the top left corner of Book Banning Birthday Parteeeeeeeee is a Taylor Swift quote: “It’s me, I’m the problem, it’s me”. It might seem a bit of a jump to equate pop culture figures like Swift and Fleabag with Trump-supporting neo-Confederates, but it is the discomfort provoked through associations like this which makes Benedetto’s work so poignant. The artist also draws a line from the States to the royalism of the United Kingdom: the royal family appears at the forefront of the wall and in the aluminium prints which crown the rest of the gallery, as photographs alongside the celebrities depicting them in movies. Lol Kristen! (2024) shows Princess Diana alongside the actress who played her in her biopic, the titular Kristen Stewart. In the accompanying show text, Philippa Snow writes of the film’s poster, in which Diana (Stewart) rests sadly in her ballgown, intentionally referencing Jennifer Lawrence’s infamous 2013 Oscars fall. “The choice of inspiration is intriguing,” Snow writes, “Lawrence was accused on social media of faking her own tumble as a way to make herself relatable… Two iconic white blonde women, and two possible styles of media training: whether we are looking at Diana’s mock flirtation with the camera or Lawrence’s clumsiness, we are never certain whether what we’re seeing is real”. Again: the performance. The criticism of white female victimhood does not make void the oppressions suffered by all women, rather it condemns the performance of this suffering.

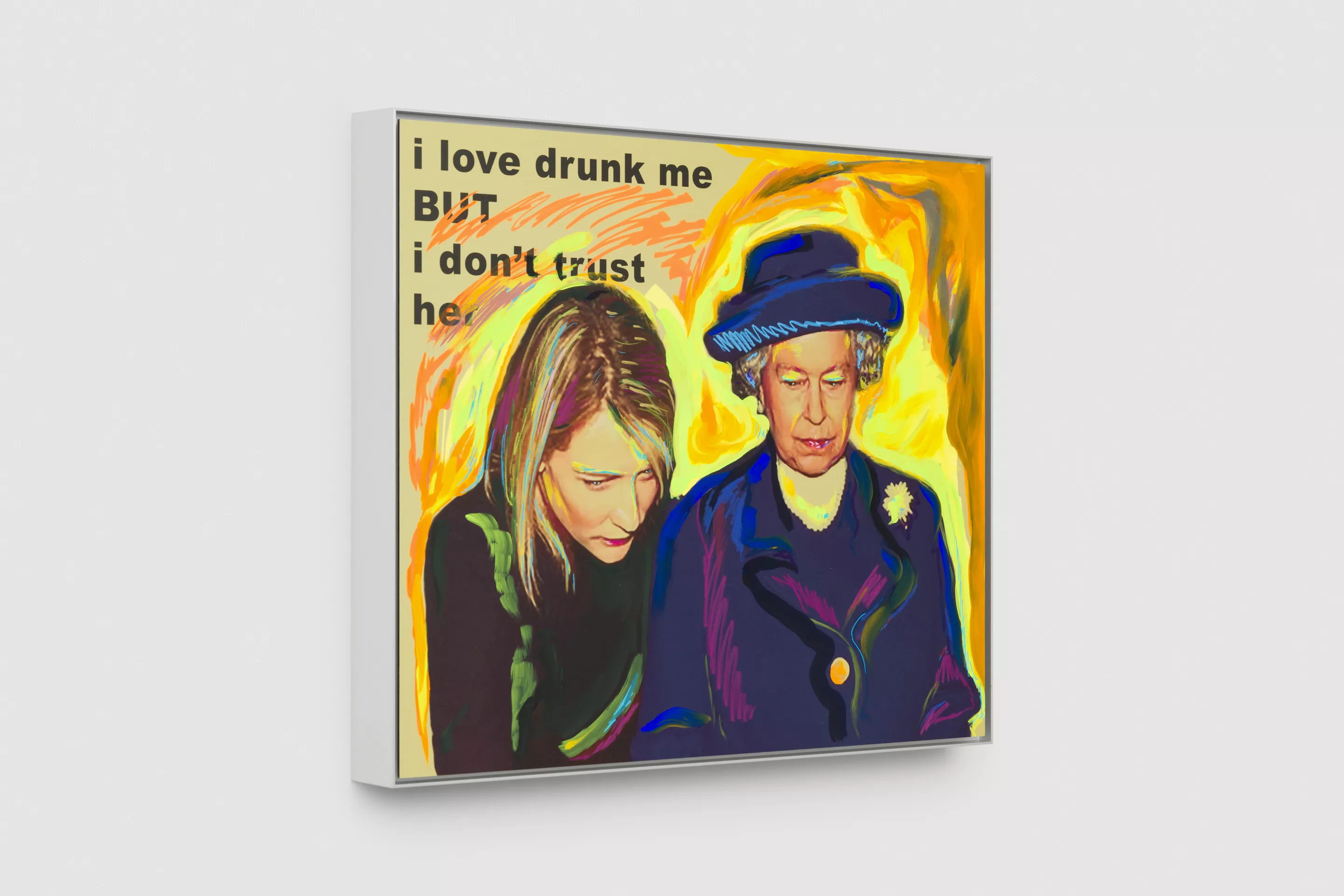

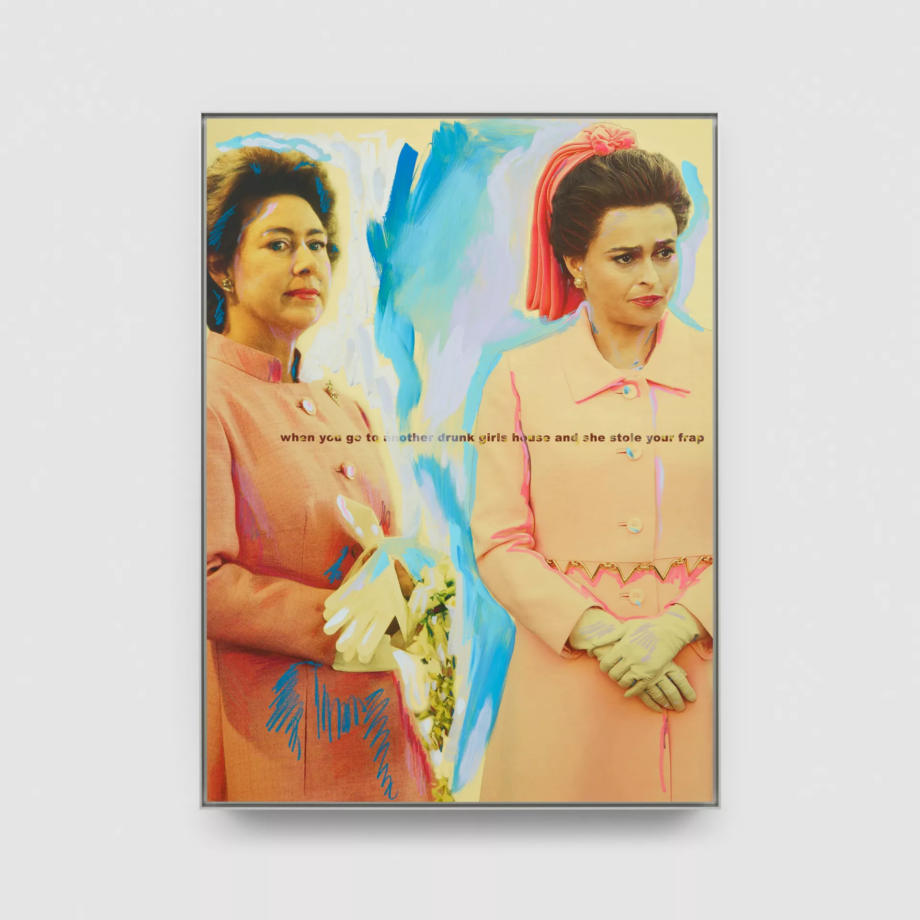

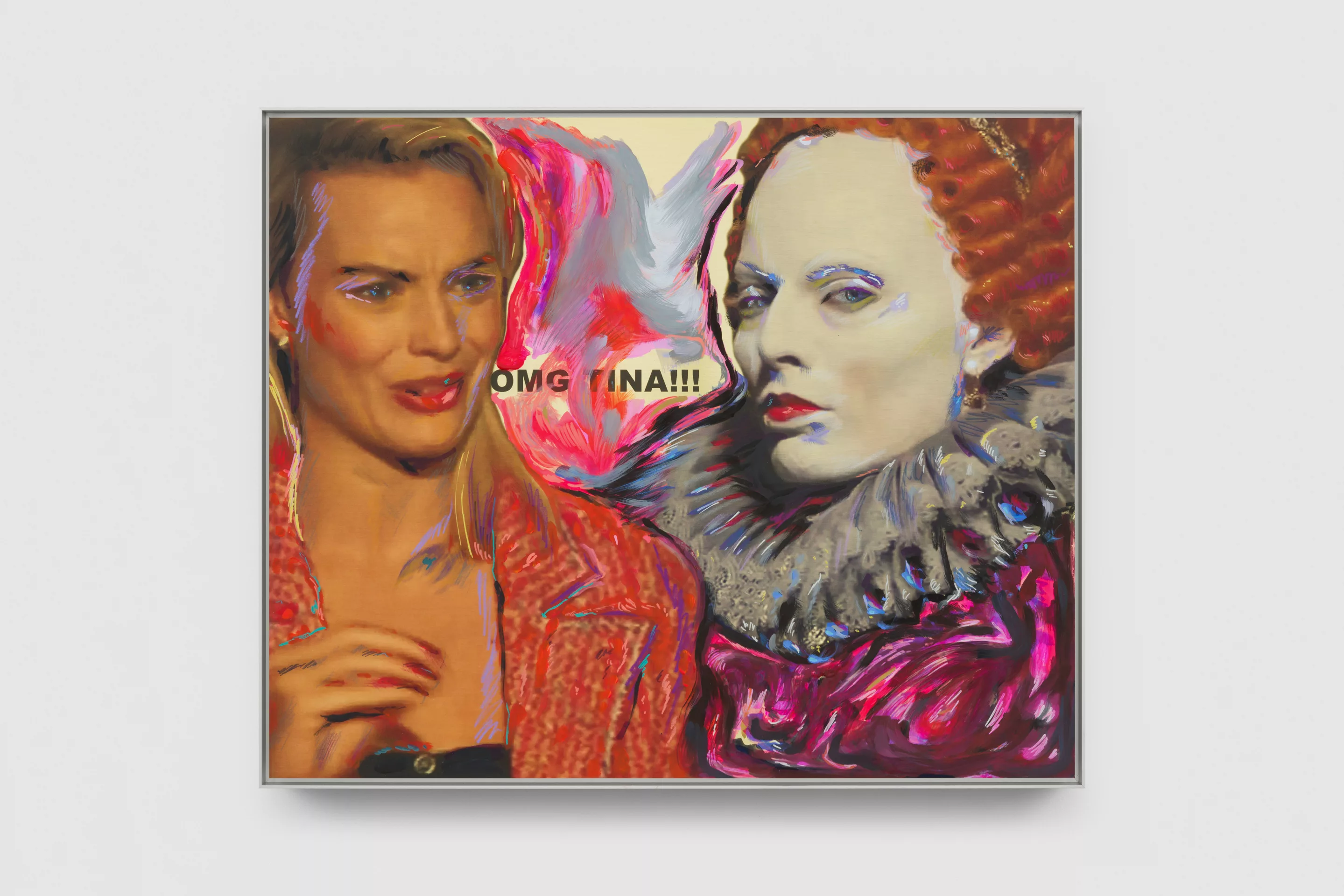

Benedetto is best known as a thinker (she is an academic, after all), and the process of making her work forms the conceptual foundation of her practice– she was trained as a printmaker. Though the prints in ‘WGW’ have an intentional naivety to them (Benedetto calls the technique “psychotic fangirling”), they are complex, made through dye sublimation on aluminium, and adorned with Sharpie, gouache, prismacolour and oil pastel. The images which the artist has transposed depict Margot Robbie as Mary Queen of Scots (Barbie Does Tina), Helena Bonham Carter as Queen Elizabeth II (frapped my pants), as well as Cate Blanchett meeting the late Queen (Don’t Trust Kitty). Here, the ‘copy’ is used as a remark on the distribution of imagery through the media (each photograph used is taken from a news source), the perpetuation of traditional (white supremacist) values and the idolisation of unknowable performed by others: the fandom.

Whilst this line of work, unlike previous enquiries of Benedetto’s, is not entirely concerned with the identity of the ‘fan’, the theoretical basis behind fandom is entwined with the ways in which the royal family maintain their power. The prints on show in ‘WGW’ take on the spectre of fan art amateurism: expressions of love imprinted upon mass-produced imagery. There is something abject about the ‘fan’, who is destined for the eternal heartache of unrequited love. Indeed, the object of their admiration does not even exist: nobody, even celebrities, is entirely their public selves. There is something undeniably erotic about collective longing and the libidinal, visceral, unsatiated ‘crowd’; fandom is entwinedwith desire. The performed white victim is in tune with this: what is more irresistible than a damaged woman in need of rescue?

In a recent interview, Benedetto spoke of a shift in identifying with or aspiring towards the destructive qualities of a public figure. Fleabag is the epitome of this: she is nasty, messy and careless. If her idolisation is a symptom of trauma as currency, it is specifically applicable to white women. Yet this type of trauma isn’t always trauma at all, it is self-inflicted destruction. By pasting Fleabag’s face across those of others in Moms 4 Liberty, Benedetto links the character to the kind of self-victimisation inherent in more explicitly problematic and political movements. In doing so, she opens up new dialogues about the covert and subtle ways in which white supremacy and white female victimhood are perpetuated in popular culture.

The nature of white female victimhood is that, though it is often posited as reactionary feminism, it frequently reinforces heteropatriarchal structures in a kind of vicious, masochistic cycle between the tears of white women and the rage of white men. Benedetto nods to this in a work titled Jubs and Dubs (2024), which depicts Hilary Clinton and Queen Elizabeth II facing each other, their eyes locked. Above them, in scrawled bubble text, are the names’ Monica + Virginia’, and below, a wince-inducing and sexually violent piece of text. It is clear as to what this references: the ways in whichthese women, who implicitly hold power, perpetuate the actions of the men surrounding them.

It also has racial implications: the performance of white emotion, whether inadvertently or not, contributes to the dehumanisation of othered people. This has its roots in slavery: the narrative of white women’s victimhood originates in myths positing enslaved Black people as sexual threats to white women. Hence, white women were good and pure, threatened only by those they did (and continue to). The politicisation of women’s pain has never extended to people of colour. Nor has it extended to sex workers and transgender women.

Investigations like Benedetto’s, which unite the gravitas of academia and research with the universality of popular culture, are necessary in rethinking our complicity in white victimhood and its prevalence in mainstream feminism– whether manifested in politics, popular culture or psychology. “Don’t ever call me a racist”, Lana Del Rey said, but it is worth contemplating how much of her sad-American-girl allure would be afforded to someone less white than her. As Benedetto reveals, the performance of the weeping Madonna is all around us– as white women, it is within us. Our tears are complicit.

Written by Ella Slater