Work hard, play hard? So the saying goes, but in the age of millennial burnout it can be difficult to distinguish between the two. Around-the-clock demands on our time have blurred the line between the office and the home, while modern workplaces are increasingly built to encourage staff overtime, taking a leaf out of the infamous Silicon Valley-style startup culture of Google, Apple and Facebook to provide fully-stocked fridges, ping pong tables and chill-out zones. From water cooler moments to brainstorming, even the language of the office has infused our day-to-day lives. As expectations of money versus time continue to accelerate in the digital age, artists have responded in recent years with their own take on the modern workplace.

Simon Denny is an artist who deals in the lingo of corporate jargon; there seems little doubt that he could stand shoulder-to-shoulder with the best of the boardroom. His is a world of globalized tech, consumerism and hyper-connectivity. In large-scale, intricate installations, he embeds himself at the heart of the corporations and government bodies (both real and fictional) who wield control over our privacy and security. He breaks down from the inside-out the workplace culture that these companies are fuelled on, with frequently absurd and hilarious results that reveal a more sinister undertone.

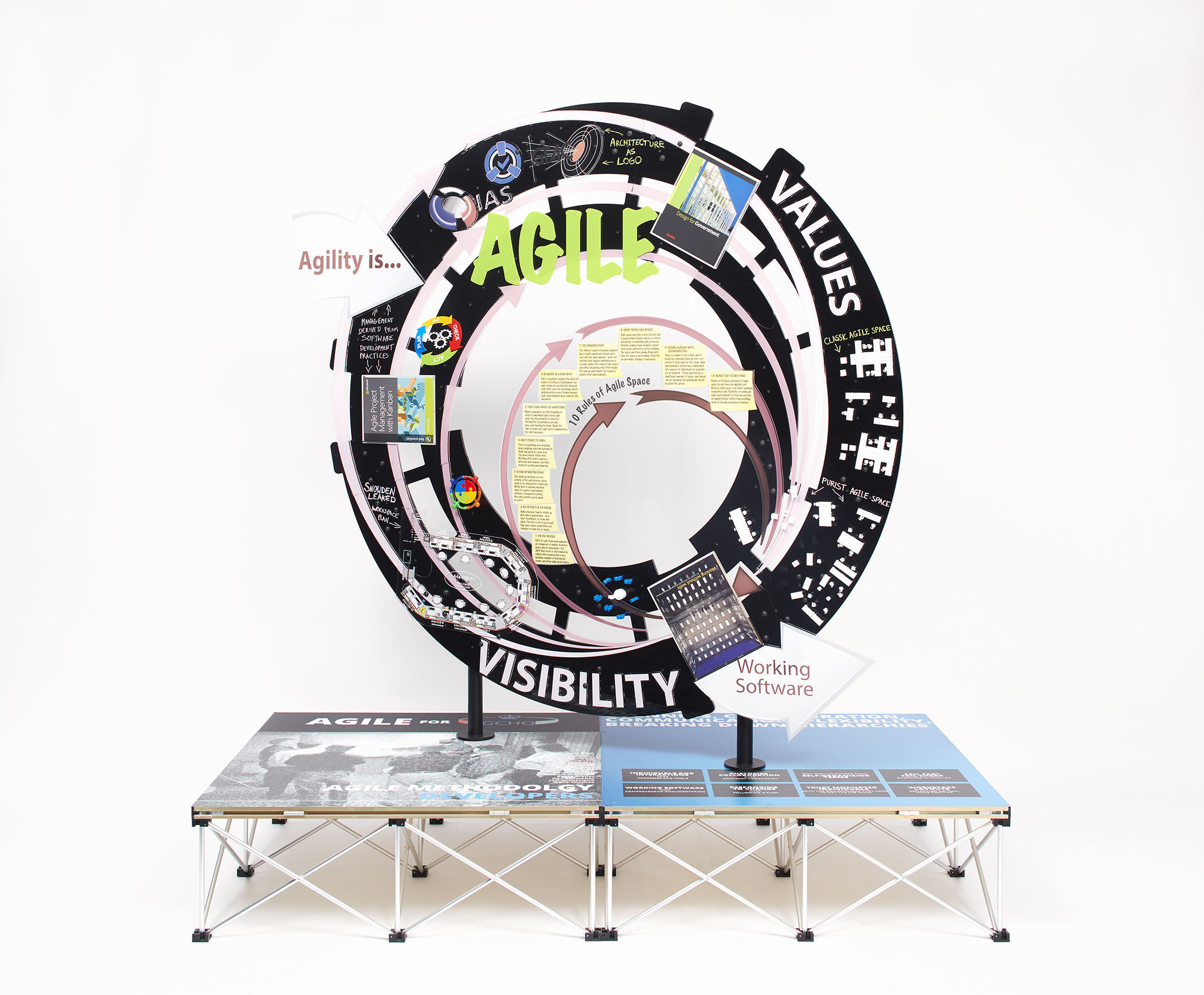

In Products For Organising, his 2016 Serpentine Gallery exhibition, motivational slogans were everywhere, shedding light on the use of visual persuasion techniques more often associated with the world of advertising. Buzzwords like “agile”, “visibility” and “innovation” decorated circular sculptures inspired by the headquarters of Zappos and Apple, their seamless curves a sly nod to the smoothing down of any “rough edges” common to company culture, in which an obsession with “fitting in” perhaps inevitably leads to a homogeneous workplace. It is no surprise that the major tech companies have been dogged by poor diversity and accusations of a “bro” mentality.

“From water cooler moments to brainstorming, even the language of the office has infused our day-to-day lives”

Camille Henrot is no stranger to the never-ceasing commitments of the modern-day workplace. Freelance life in the digital age requires an endless checking of emails; the ruthless online attention economy is never satisfied and demands an active presence at all times. I tend to think that people can be categorized into two groups: those who obsessively keep their unread emails at a perfect zero, and those who hopelessly throw themselves to the tides of thousands of unopened messages. Henrot is well-versed in the myriad memes, references and other digital ephemera that we navigate each day, but it was her 2016 installation, Office of Unreplied Emails, that spoke most directly to this condition of avoidance and anxiety.

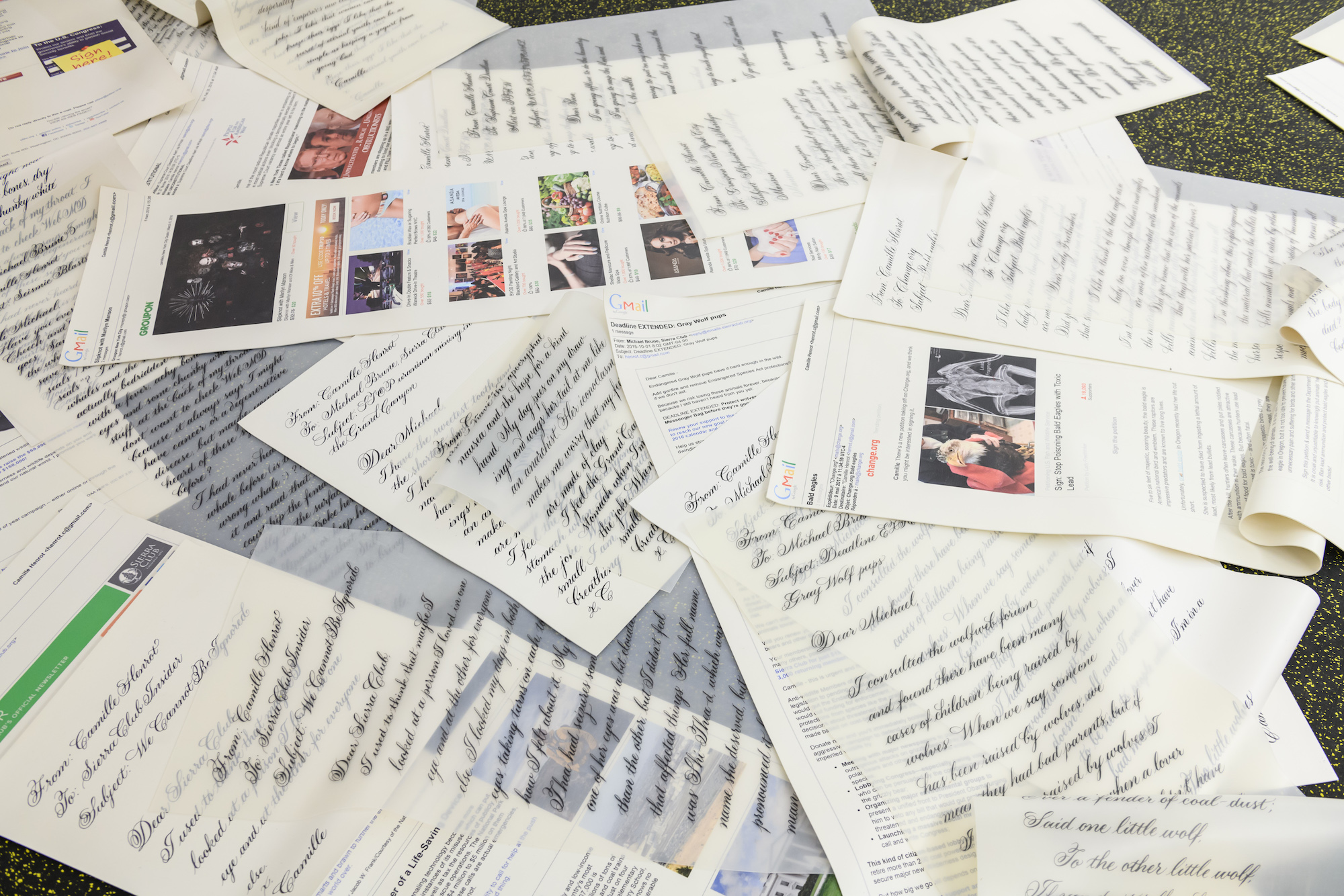

Henrot collected one hundred unanswered emails for the project (created in collaboration with Jacob Bromberg), focused mainly on the various communications from charities, online petitions and stores that land in her inbox each day. In response, she penned overwrought, emotional and reflective messages to each, written out in an exaggerated calligraphic script, expressing sympathy while considering the implications of the never-ending cacophany of requests for our undivided attention.

“Office of Unreplied Emails came after a deep moment of thinking about politics and ethics. I was receiving more and more emails from places like change.org. They communicated in a way I found very compelling, by using my name. ‘Camille, don’t let the oil companies take control!’ Of course not, I can’t let them!,” she explained in an interview in 2017. “I felt that I had to do something, and that participating in these causes was more important than my work. I was signing petitions, donating money, and it was never enough.”

Modern anxiety and the ongoing shift towards automation is taken to its extreme by Josh Kline in Unemployment (2016), in which he imagines the year 2031, an era when workers have been rendered completely obsolete. Lawyers and accountants, 3D-printed as disturbingly realistic life-size mannequins, lie curled up inside clear rubbish bags. Dressed in the bland suits and kitten-heels that have long constituted the uniform of the modern professional, they are reduced to trash, stripped of their purpose, status and bank balances. The message is clear: the labour market is ruthless, with the mentality of every person for themselves in an age of accelerated, global neoliberalism. As virtual workplaces and zero-hour contracts increasingly become the norm, it no longer seems like much of a leap of the imagination.

“Freelance life in the digital age requires the endless checking of emails; the ruthless online attention economy is never satisfied”

Urs Fischer, meanwhile, offered up a lighter tone in his recent Play exhibition at Gagosian in 2018, featuring nine office chairs programmed to “dance” throughout the expansive, open-plan space of the gallery. Put together with choreographer Madeline Hollander, the anthropomorphized chairs take on a life of their own, waltzing and gliding with one another. A surreal air of romance is injected to the humdrum office environment. These ergonomic chairs, with their curves and padding designed for comfort and productivity over aesthetics, are suddenly given a newly tender side; sure, they might not be the prettiest of objects, but don’t they deserve a shot at love and laughter too? Their wheels a-rolling, their seats a-swivelling, they have come out to play.

An equally surreal story played out in Amalia Ulman’s exhibition Reputation, installed at New Galerie in 2016. Set in an office space, complete with biros, white board, paper clips, box files and (naturally) a desk chair, it followed the curious tale of Bob the pigeon, an alter-ego of sorts for the artist. Ulman lives and works in Los Angeles, and the office that she chose to portray was inspired in part by the real-life studio that she occupies in the city’s Koreatown. The corporate rent-a-unit block is occupied by a range of white-collar professions, in stark contrast to the more typical expectations of the light-filled, bohemian clutter of the artist studio. From here, Ulman was able to broadcast a series of short videos and photographs via her Instagram account, expanding upon a social media-focused practice first established with her 2014 series Excellences and Perfections.

Her vision of the office is rendered in a strict colour palette of red, white and black, suggestive of everything from classic typewriter ribbons to the tragi-comedy of French mime. Black-and-white sketches directly reference the New Yorker’s long-running cartoons, with nods to Monday morning blues, petty disputes and banal betrayals. The status of Ulman as both artist and businesswoman is drawn into question, as well as our own assumptions and expectations of the attire, personality and value of each role.

“As more people than ever before go freelance or work from home, the office may finally come to represent a nostalgic space”

For Thomas Demand, the nuances of the familiar spaces and everyday objects that we live and work with are integral to his exacting practice. At first glance, his photographs of everything from an airport security desk to a discarded coffee cup show a keen eye for the often-overlooked details of our contemporary environment. Look closer, though, and you will see that each and every item is made from paper, painstakingly constructed to form life-size models that he later photographs and finally destroys.

The humble office is a natural fit; Post-it notes, photocopiers and assorted stationery are a common denominator in workplaces across the globe. As he explained in an interview with Elephant last year, “Whether you go to an insurance office or a hospital, it basically looks the same. We all share the same spaces, but the narratives are very different.” His uncanny, unpeopled images of the work environment invite reflection on the generic and the mass-produced, where the individual is absorbed into the wider team and company ethos reigns supreme.

At a time when it has never been easier to work outside of the office, with wifi, informal co-working spaces and countless apps for staying in touch, the typical office as we know it may be on the way out. The office of the future is a far cry from its most memorable portrayals in popular culture, whether in television comedy The Office or cult-classic 1999 film Office Space. As fax machines, photocopiers, phone lines and computers continue to shrink and streamline, there remains little to demarcate an office at all beyond a laptop and internet connection. It is perhaps for this reason that artists have chosen to focus on the aesthetics of the office in recent years, reflecting upon this shift in contemporary culture even as the pressure and drive to work harder has accelerated.

As more people than ever before go freelance or work from home, the office may finally come to represent a nostalgic space—one where stolen staplers and printer jams were the main anxieties of the day. Instead, the deeper, more insidious concern of zero-hour contracts, chasing invoices and an unregulated labour market have taken hold, leaving us with more than a twinge of longing for the old (to paraphrase Dolly Parton) nine-to-five.