The recipient of the inaugural 2023 East London Art Prize, Kat Anderson’s solo exhibition Mark of Cane at Bow Arts’ Nunnery Gallery comprises the premiere of the short fictional film Las, Fiya (‘Last, Fire’), and three new paperworks, Untitled 1–3. Running until 21 April, the exhibition frames a coming together in an exploration of inherited trauma, the intersection of socio-economic realities with legacies of colonial extraction, and the interplay of de- and re-possession. When the film plays, the 2D works are animated by the interplay of the projection’s light upon their glass encasings – the triptych of static works is made mobile, echoing the film’s challenge to a fixed notion of history, the essence of recapitulation and revision at the heart of its message.

Turning off the main road in the heart of East London, one enters Bow Arts’ Nunnery Gallery as one might seek domestic respite – an appropriate entry into the watching of a film that frames home as a site of endless return. In Las Fiya, Anderson plays Lil alongside Fiya Ras 1, the latter translatable as a large ball of fire. Over the course of 26 minutes, we witness her possession by and regurgitation of unheard and unprocessed trauma. The protagonist’s transgenerational pain plays out across the screen as we witness her wrangling with agony and eventually enacting revenge. The film illuminates the profound legacy of the vagaries of the sugar trade in the Caribbean – the wounds upon the flesh of the children, of the children, of the slaves first tasked with tilling the lands, and the perversity of the trauma-tourism that forces descendants to re-enact activities of oppression for traveller-audiences. History is framed as a cyclical venture, echoed by the repeated shots of the tourist bus journeying down the island road.

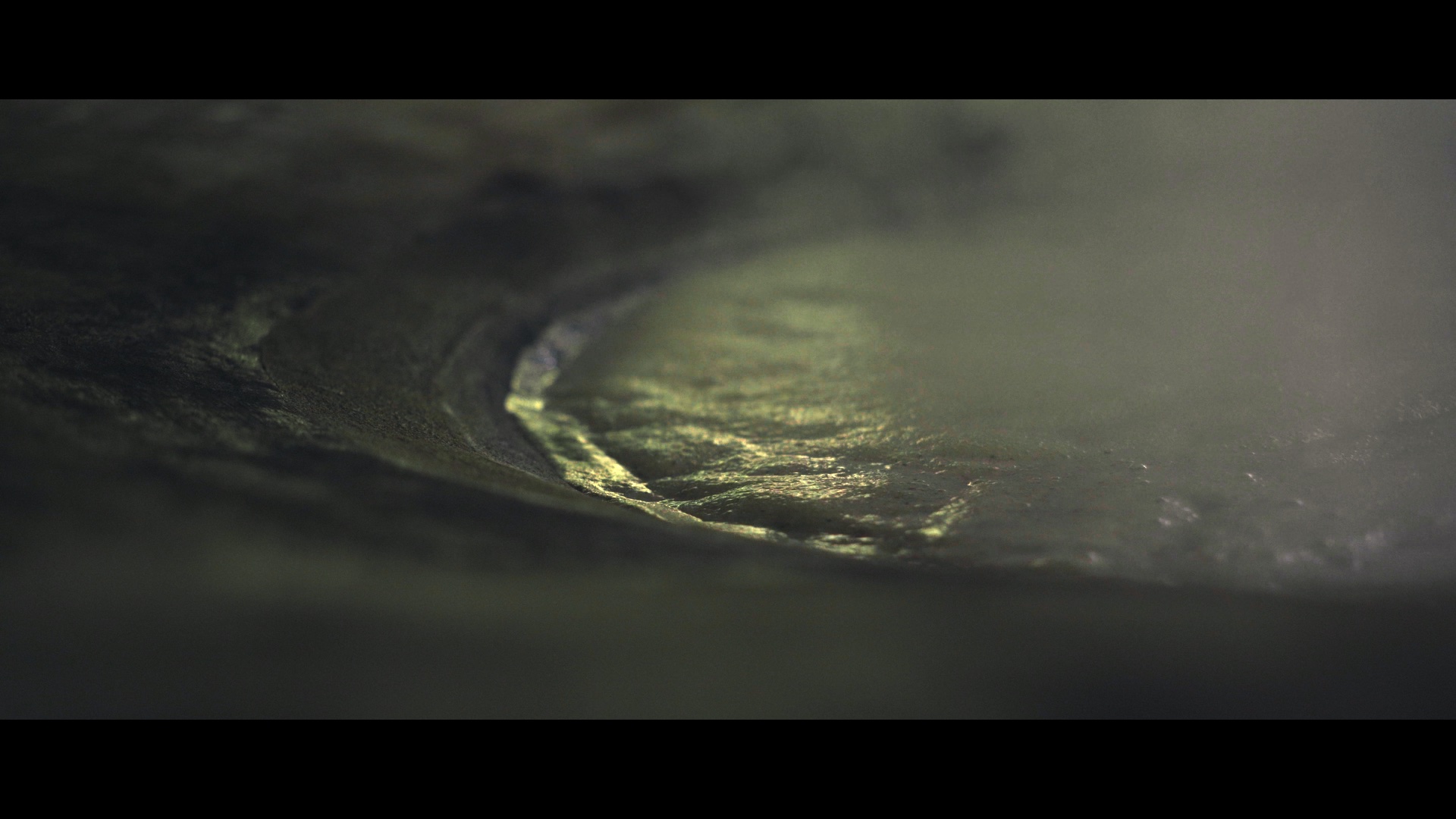

Primarily shot on an existing sugarcane farm in Jamaica, past and present are bound and brought to the fore: emanation and extenuation confer within the cinematic subversion of the ‘origin story’ trope – traditional harvest methods are framed in the elucidation of history, but Anderson rejects explanation; our subjectivity is framed within the legacy of the extraction and refining of sugar, but the side of the story in which we are implicated is left to the self-determination of the viewer. Whilst touring the plantation, the recurrent focus on the perennial rushes of the sugarcane is intercepted by a single, remarkable shot of the ocean: the logic of viewing one nation as an outsider is framed in the half-oval porthole to the Caribbean Sea. The body of water sits in focus whilst a member of the tourist group remains unfocussed in the foreground; as representative of the colonial mission, the visitor’s encroachment upon the pictorial frame forms a direct evocation of the imposition foreign bodies upon the island landscape, as a symptom of the Atlantic slave trade.

Las Fiyas problematises the notion of one’s place of heritage as fertile ground; indeed, one of the first lines of dialogue queries Kat’s presence on a touristic survey, despite her hailing from the ground to be covered. The theme of re-discoverability is instantly established, asking what it means to be a tourist in your own home. Extrapolated into the context of Tower Hamlets, one of London’s most diverse boroughs, enfolded are reminisces of racialised vocalisations – malintent levied at those traversing roads upon which their subjectivity is necessarily minority; an ironic nod to the sadly ubiquitous experience of being told to “Go home.” For first, second and third-generation immigrants, the notion of return is inherently convoluted – one is at once home and a stranger in both the remit of removal and the habitat of heritage, simultaneously and inextricably. The conflict of the demand that one leaves and the desire to return, is augmented by the scenic scoring of Edric Connor’s ‘Time for Man to Go Home’ – crooning calypso rhythms narrating a folklore of resistance and retrieval, backgrounded by an image of a rain-misted grassy mound.

The film functions as part of Anderson’s wider project ‘Episodes of Horror’; aptly the filmic legacy of a Kubrick-esque horror is evident, characterised by film noir mise-en-scene and pitch-black humour. A refined but strong colour palette is crafted by interstices of red light, framing the narrative through the lens of ichor. Tracking scenes are woven amongst Sergei Eisenstein-style montage – from the sea to swaying reeds and crops, from the verdant Jamaican landscape to the carmine-tinted signifier of the Force. Within the sensorial assault, we alternatively focus on single objects and constellations of items as scene setters – the dressing table in the room of a sleeping guest, a single croc bearing the visage of Bob Marley, abandoned in the grasses of the plantation. In the case of the latter, the device functions to foreground the sinister vein of the film, juxtaposed with the assumption of a carefree island existence, in wilful ignorance of the aftereffects of colonial exploitation.

Notable also, is Anderson’s use of subtitling as a device beyond the simply interpretative. The narrator speaks of their return in terms of “i(s)landing”, evoking the motif of the archipelago as a metaphor for the complexity of multicultural subjectivity. During portions of the film, it becomes unclear whether the captions correlate to the distorted flanging tones of the supernatural narrator or are operating as an additional illustrative device; the essence of translation is manipulated, playing with comprehension and opacity in a Glissantian manner.

And then – the climax. The tourist’s tour concludes with a sampling of sugarcane juice, the historical manner of distillation demonstrated to their voyeuristic glee. With the first sip of the extracted liquid, we reach the apex of Anderson’s conceptual intention: the enactment of a mythopoetic process in pursuit of catharsis or the transformation of trauma. The visitors to the plantation are poisoned by the sugar cane juice; their degradation plays out in fits and starts amidst thumping drum and bass as blood drips from eyes and the nebulous voiceover grunts and cackles in the gathering dusk.

The exhibition’s titular pun is revealed, and the Mark of Ca(i)n(e) evoked (with reference to the designation by which the son of Eve was anointed in the Bible, confirming that any who harmed Cain would find the inflicted damage re-enacted on them sevenfold). The message is clear – here is reparation. With an awareness that the UK only completed paying off “compensatory” debts to slave-owning families in 2015 (owing to the 1837 Act of compromise that facilitated the consolidation of abolition), the ominous intonation of “Your debt is waived” holds profound significance. The western-capitalist proclivity for undiscerning consumption is served its comeuppance: the imperial desire to ingest anything and everything, even that not for you, is illuminated and condemned.

A Brechtian dissolution of the fourth wall is inputted via the suggestion of a film within a film: several scenes chart Anderson placing green tape over her eyes and mouth, and donning green gloves as a faceless suggested-director-character speaks with variable legibility in the background. The purpose, with specific reference to the film’s title, is divulged at the film’s conclusion – revealed to be for the device of green screen, we see her appendages burn: emblematic of the spiritual scorching and subsequent cleansing framed in Anderson’s parsing of retribution. As the screen fades to black cars can be heard it is unclear whether these are residual sounds of the film’s track or the rumbles of vehicles heard from outside on Bow Road. The performative convention of meta-cinema is framed; even as we have suspended disbelief in the presentation of the otherworldly, we are brought back to earth with the remainder of the real-world and affective themes Anderson’s work explores.

One wonders whether the film fails to take the opportunity to shed further light on the compacting of sugar and its micro-societal impacts – to delve deeper into the workers of contemporary plantation workers as their lives correspond with that of their ancestors. The key of emotion is relentlessly rageful; the narrative arc is somewhat atypical – the climatic escalation is accelerated; the conclusion lacking any nuance in its moralistic agenda. Turning from the conclusion film to the exit, one’s eyes are drawn back to the three pieces of paperwork on the opposing wall. Crafted using a novel artistic process and adopting sugar as material and medium, the works frame the capacity for the use of sugar beyond its commercial aspect as codified by the slave and sugar trade. In the transformation of material purpose, one is reminded of Audre Lorde’s The Uses of Anger. We are not simply left to ponder on the atrocities of the transatlantic legacy but invited to think through and beyond. Anderson’s resistance of universality is ultimately purposeful: this is not a historical survey of the sugar trade but the revelation of the specific manifestation of the torment that acceded to an individual against their will. Whether one finds affinity with Anderson’s character or the contextual material or not, the viewer is moved to emotion – to think how we embody a Lordean fury of virtuousness and productivity and engage in reclamation – to be affected is the purpose of art.

Written by Katrina Nzegwu