As Boris Groys states in After the Big Tsimtsum, “Pavel Pepperstein is quite clearly more than just an artist. He is also a poet, writer, critic, curator and theorist. Above all, however, he is a designer of social spaces.” This is true – he is all of these, and more. Pepperstein is an intellectual rebel, an articulate revolutionary – a romantic personality that in some way resonates with us all. From co-founding the group Inspection Medical Hermeneutics in Moscow during Glasnost in the late eighties up until his most recent collaborative series Ophelia with his father, Viktor Pivovarov, at Regina Gallery in London, Pepperstein has never ceased to create escapist, fantastical visions which function as alternative ‘spaces’ to the reality of the world today.

Reappropriating Constructivist symbolism and using it in a style somewhat akin to the fairy-tale imagery of both Russian and Soviet literature, Pepperstein’s artistic output has come to reflect the post-Soviet mindset of his generation. Born in 1966 and growing up in Moscow during the socio-economic stagnation of the Brezhnev era, Pepperstein and his contemporaries reached maturity at an unprecedented moment in history, when the Soviet Union was on the point of collapse. Rather than welcoming in the capitalist project and the prospect of liberty, he instead began to question social and political structures in order to identify his place in the system. This externalization of a particular consciousness has further significance, as this dissident stratum of Russia’s society, which shows little interest in the politics of capitalism, is still relatively unfamiliar to the Western audience.

Inspection Medical Hermeneutics / Medgerminevtika

After studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague in 1985–87, Pepperstein soon returned home. Almost immediately he met the artist Sergei Anufriev in the now legendary Furmanny Lane studios, a creative space for nonconformist artists which functioned as a Muscovite version of Warhol’s Factory in a squat-cum-studio in Furmanny Lane in Moscow and was the first port of call for anyone interested in contemporary art in the Gorbachev period. Realizing they shared similar viewpoints on both culture and politics, they co-founded Inspection Medical Hermeneutics in December of that year. As the collective’s cryptic name suggests, the men led a pseudo-methodical investigation into the study of interpretation through lectures, performances, conversations, installations and conceptual artworks. Later joined by Yuri Leiderman, IMH soon came to embody this spirited counterculture, representing a faction of society that demanded a different approach to the changing socio-political landscape of the time.

They began to record their conversations as they sat round a table articulating abstract ideas about philosophical notions of human existence. For these young men, round-table discussions were not unusual. In fact, the spoken format acted as a simulacrum of events which the young Pepperstein had witnessed whilst growing up around his parents’ nonconformist friends. His father was a leading member of the artistic collective known as the Moscow Conceptualists and his mother, Irina, was both a poet and an author of children’s books. Due to governmental restrictions in culture and the arts, many artists of his parents’ generation would use the officially sanctioned medium of book illustration to make a living. Whilst doing so, however, they would find other, unofficial ways to advocate freedom of expression. For example, Ilya Kabakov famously used his front room as an unofficial exhibition space during those turbulent years. Similarly, Pepperstein’s parents would subversively open their doors to the underground cultural intelligentsia, turning their home into a clandestine haven of free thought and discussion.

The first of IMH’s nine discussions was entitled Contraceptive Conversation about Freedom. With a Trinitarian subtext in evidence, the three men imagined themselves as gods sitting round the table. While discussing ideas, they would pass round snowballs, the circular forms representing an orb-like perfection. As the ice slowly began to melt, the gods deteriorated into humiliated mortals, drenched in the dirty water. Aside from the poignant symbolism, the essence of this work remained in actions discussed and never realized. The dialogue itself became

the performance; the spoken words held sufficient gravitas.

When Vladimir Fedorov replaced Yuri Leiderman as IMH’s ‘Senior Inspector’ in 1991, Pepperstein assumed the lead role. Pepperstein had fronted ‘NOMA’, an acronym he outlined in Andrei Monastyrsky’s Dictionary of Moscow Conceptualism as representing ‘a group of people who describe the boundaries of the self by means of a set of language practices that they have developed together’. It was this focus on language and its importance that formed the epicentre of the group’s practices, and continues to feature in Pepperstein’s work to this day.

It is not surprising that at times Pepperstein has worked almost exclusively in black and white. He saw the monochrome palette as being most similar to text itself. Commonly, Pepperstein would paint directly on to the wall as a reference to an archaic technique. Not only did the wall symbolize repression, symptomatic of the communal living standards of his father’s generation, it also represented a medium that was patently anti-consumerist. This idea was exemplified in the late nineties when Pepperstein decorated the walls inside important Swiss buildings with his blackand-white watercolours, including one downtown prison, as part of ‘Projekt Sammlung’ at Kunsthaus Zug. He covered the inside walls with the evocative imagery of a journey from the depths of Hell through open landscapes and beyond. This allusion to a metaphysical rise from the underworld was further juxtaposed with a series of anonymous male portraits that recurred throughout his time with IMH.

In 1995 Pepperstein created a similar series of monochrome portraits for the IMH installation A Pipe or an Alley of Longevity. The installation consisted of a room where, suspended from the ceiling, a tubular structure compositionally cut the room in half. Using binoculars, the audience was encouraged to view a miniature uninhabited room at the other end of the tube. Lined up along the opposing walls of the installation were, once again, a series of Pepperstein’s monochrome watercolour portraits. One wall featured a lineage of old, decrepit men, with absurdist ages escalating to billions of years. Opposite hung a series of boys’ faces (known as Kolobok), their ages farcically decreasing into minus numbers. The installation provided an unsettling suggestion of the binary cycle of life and the timeless anonymity of portraits on prison walls. The tunnel offered a vital sanctuary, and perhaps a means of escape, from this fantastical hyperbole.

Rebuilding Russia

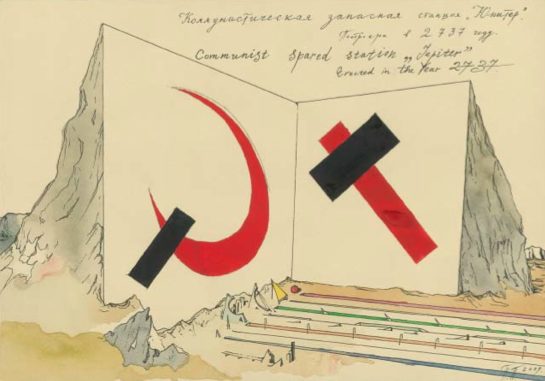

The notion of ‘sanctuary’ became a recurrent theme as Pepperstein sought refuge from the dissatisfaction of mainstream political discourse. Published in 1993 in Ilya Kabakov’s NOMA exhibition catalogue NOMA oder Der Kreis der Moskauer Konzeptualisten (NOMA or the Circle of the Moscow Conceptualists), Pepperstein’s quasi-manifesto ‘Report NOMA – NOMA’ openly discredited the iconoclastic destruction of propagandist monuments in the era of post communism. For Pepperstein, these cultural signifiers had acted as a fundamental and collective memorial to his nation’s secularized past. By way of compensation, Soviet iconography is incorporated in the artist’s semiotic language as he reframes the past into a whimsical yet enduring vision.

In 2001, in the aftermath of 9/11, Pepperstein was galvanized by a brooding sense of discontent and displacement. For the artist, the act of terror laid bare the limitations of socialism, a system that he had spent decades upholding, and he tells us: “Inspection Medical Hermeneutics ceased to exist on September 11th, 2001, after the tragedy in America. It was our joint decision. Even though we wanted to continue and had lots of ideas, we decided that there is no more a place for our activities. On September 11th, 2001, our world (our socialist world), which we represented and worked for, vanished. This world has created us, and was the barrier between progressive capitalism and the developing Third World. We understood socialism not as a political or economical system but as a way to save individual souls.” As this barrier had proved to be spectacularly ineffective, Pepperstein now found himself wholly disenchanted. Thus, in the post-9/11 period, Pepperstein’s appropriation of the iconography of his mother country becomes conspicuously more tongue-in-cheek.

In 2009 Pepperstein represented his country at the 53rd Venice Biennale in the Russian Pavilion Victory over the Future. Through the medium of watercolour and oil on canvas, Pepperstein vibrantly depicted a futuristic Russia, as can be seen in Black Cube Skyscraper (aka Malevich Tower) Will Be Built in 2042 to Serve as the Main Residence of the Russian Government (2007). An imposing black building shaped like a cube soars above the surrounding city, while people parachute through the sky. At once, Pepperstein reminds the viewer of acclaimed, unrealized propagandist projects of the Russian constructivists, Lissitzky and Rodchenko. It is through this reference that Pepperstein conflates time with unparalleled singularity. With his usual parodist’s manner, and using the iconography of yesteryear, he plans an alternative and utopian future, a limitless fantasy based on a semiotic interplay with the historiography of Russia.

At the very time that Pepperstein was producing hyperSoviet illusionary ideals, he was also using the same medium to create other non-worldly fantasies in a manner that he brazenly terms ‘philosophical pornography’. Interchanging Malevich’s Black Square with an erect penis in T

he Lingam Tower Was Erected over the city Russia in 3004 (2009), Pepperstein once again transgresses time by symbolically interchanging the venerable monuments of his past with idols of a new super-charged future. Asked why eroticism and erotic symbolism recur in his work, Pepperstein responded, “I very much dislike the word “erotic” and really respect the honest word “pornography”… My wish is that all people would masturbate all the time. My dream is to become the best porno producer in the world. I request that all your readers interested in working with me in this field (in any capacity) should get in touch with my agent in London.” Representative of his sardonic humour, this intentionally provocative statement illustrates Pepperstein’s nonchalant attitude to typically subversive matters.

Counter-revolution

At the Venice Biennale, Pepperstein hypnotized his audience into a different level of consciousness with Future, a ten-minute rap, vocalised over a synthetic beat. By experimenting with this contemporary medium, Pepperstein brought his unknowing audience into the underground world of rave culture. The pounding beats and guttural intonation broke down the confines of what he considered to be the institutionalized elite, mesmerizing them with his expletive mantra. Rapping ‘Hey Western teacher, let our kids alone. Understand?’, Future vocalized the colonization of Russia by the West and reinforced the Russian people’s frustration at this turbulent scenario. Thrust from the surrounding Pavilion straight into confrontational rap, Pepperstein’s audience was unwittingly infiltrated by his psychedelic frustrations.

In terms of the spoken word, and what it can provide that images cannot, Pepperstein pays homage to a time in Russia when dialogue was the main source of information for people who refused to succumb to the governmental prohibition of the arts and free expression. He says ‘There is a difference in the importance of images and words in Russia and in the West. Here a word is much more important. Rap addresses a different audience compared to the audience for contemporary art. Moreover, this is not simply a different audience. My rap audience is antagonistic towards the art world. My raps address people who want the art world as it appears and functions today to cease to exist.’ By playing this rap at the Venice Biennale, Pepperstein purposely sought to antagonize, magnifying the social hierarchy prevalent in the arts.

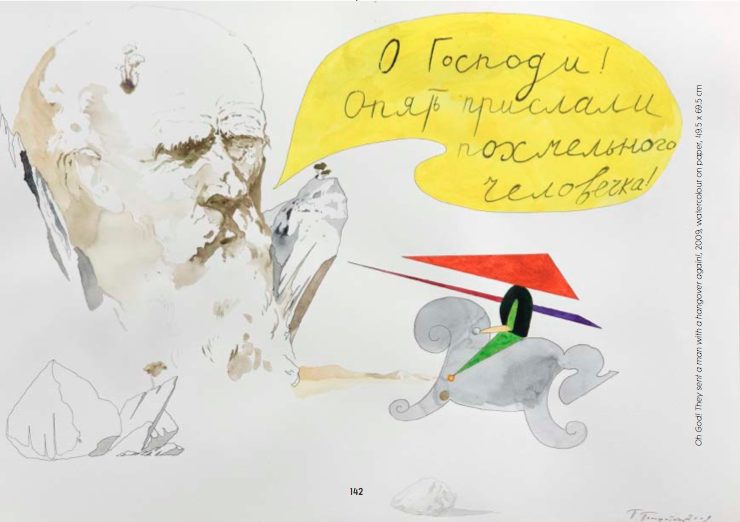

Furthermore, this fastidious use of language, coupled with a shrewd understanding of his targeted audience, illustrates Pepperstein’s strong command over the spectrum of the written word. Since forming Inspection Medical Hermeneutics, he has written and co-authored novels such as the fantasy The Mythogenic Love of Castes and the detective novel The Swastika and the Pentagon, receiving the coveted GQ Writer of the Year award in 2007. Moreover, Pepperstein reverts back to the nonconformist tradition of illustrating the books himself, as it was through this largely uninhibited medium that dissenting artists found a way to channel their creative urges. Pepperstein wrote and illustrated the extraordinary A Prague Night in 2011, a novel that was nominated for two Russian literary awards. Written in the first person, the stuccoed narrative follows an assassin through a sophisticated plot to kill his victim. The reader is enticed into a tale full of violent and passionate twists and turns, brutal realism, striking metaphor and dark, foreboding humour. As the text lures you further into the inner consciousness of the poet-turned-hitman, Pepperstein juxtaposes sharp, sophisticated, graphic illustrations, which augment the drama and increase the pace of this fantasy thriller.

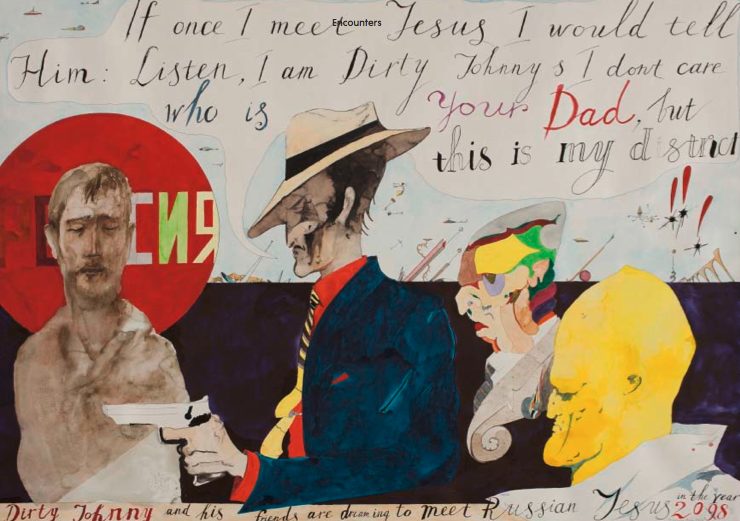

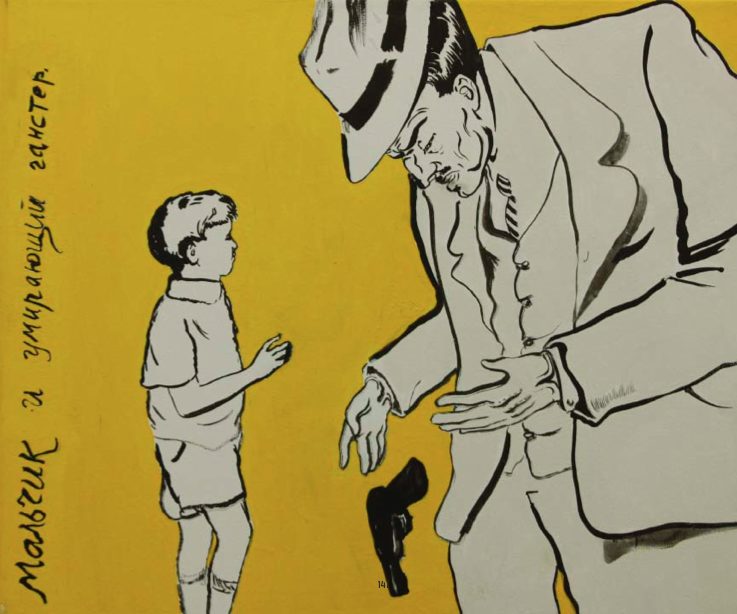

By these means, Pepperstein nods to the underground comic-strip culture of the younger generation, distancing himself from the high-end stereotype of the contemporary art scene. Indeed, it is no surprise that the ‘gangster’, a symbol of subversive rebellion, is a favoured character in Pepperstein’s work. In the cartoon-like painting A Boy and the Dying Gangster (1996), an innocent young boy seemingly outlives his once-threatening nemesis in a modern take on the David and Goliath story. Could it be that, after all, the rebel gets defeated?

The Peeperkorn Mythology

“I adopted the pseudonym Pepperstein when I was around 13 years old,” Pepperstein has revealed. “This was after I read Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain in which one of the characters is called “Peeperkorn”. I altered the name “Peeperkorn” so that it sounds more Jewish.” Ultimately, it is this aspect of the story that is the most remarkable of all. Seldom leaving his country or visiting his international exhibitions, the artist has become a figure of folklore; a wanderer with no fixed address. Asked if this escapist lifestyle was a deliberate attempt at disengagement, he replied: ‘I tend to exist as a nomad. I never stay long in one place. This is not because I hide from my audience but I simply follow my mood.’ His absurdist, provocative and sometimes humorous tone is in part the product of this nomadic existence, one in which the imposed systems of mainstream society have been openly rejected. Pepperstein’s work attracts a like-minded audience – one that is capable of embracing alternative sensibilities.

He is characteristically unapologetic. When Victor Tupitsyn asked Pepperstein if the ‘artist’s intention’ was lost when his works were seen out of the specific context in which they were created, he quipped, “I address it with a very simplified message: “Like the picture? Give me the money, take the picture and fuck off…” All that interests me in this case is what’s happening here, in Russia…”