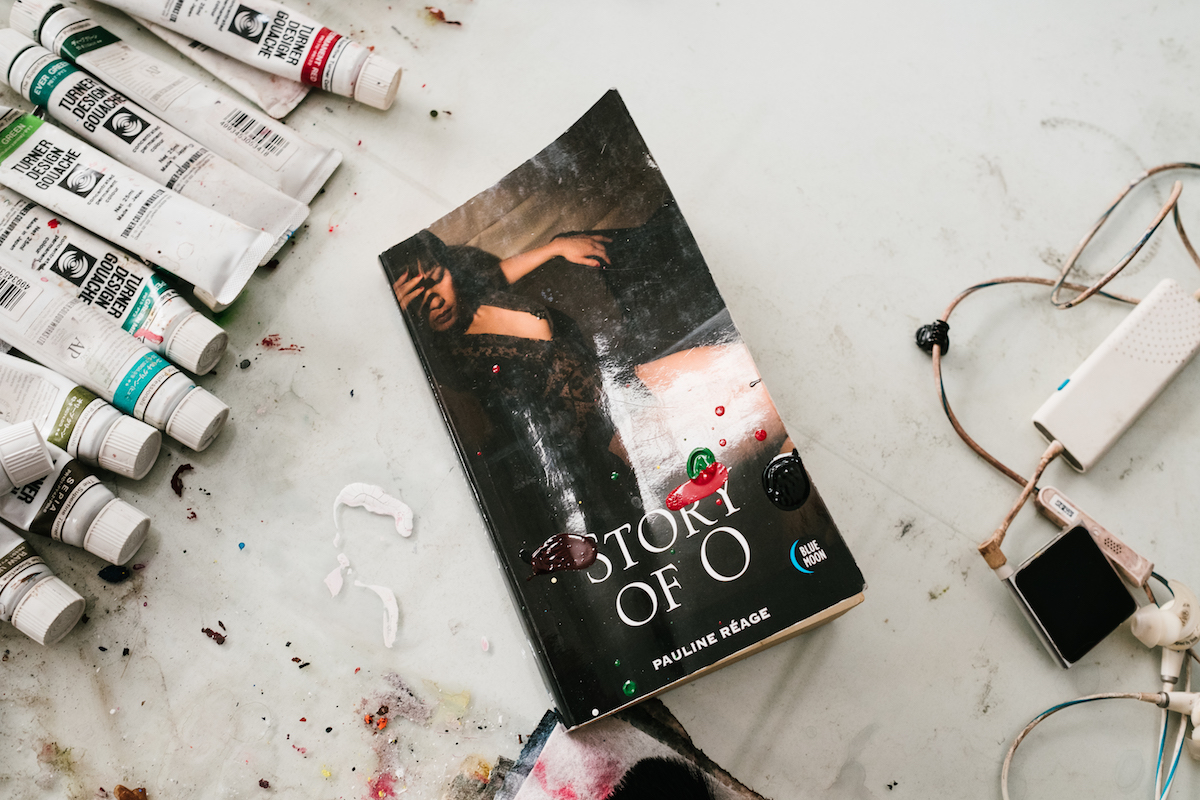

I met Natalie Frank in her Brooklyn studio, where she told me about her latest body of work: a series of drawings and paintings illustrating the scintillatingly hot Story of O, to be unveiled in a solo show at New York’s Half Gallery in May. Penned by French journalist Anne Desclos under the pseudonym Pauline Réage in 1954, the once-banned novel follows a young Parisian photographer named O who is taken as a submissive by her lover, initiating her into a secret sex society where she explores intimacy, domination, and her own desires. It’s 50 Shades of Gray if the recent pop-lit hit was actually risqué.

I met Natalie Frank in her Brooklyn studio, where she told me about her latest body of work: a series of drawings and paintings illustrating the scintillatingly hot Story of O, to be unveiled in a solo show at New York’s Half Gallery in May. Penned by French journalist Anne Desclos under the pseudonym Pauline Réage in 1954, the once-banned novel follows a young Parisian photographer named O who is taken as a submissive by her lover, initiating her into a secret sex society where she explores intimacy, domination, and her own desires. It’s 50 Shades of Gray if the recent pop-lit hit was actually risqué.

Frank’s illustrations of Story of O are more than just a bawdy interpretation of BDSM, though. They’re cleverly provocative and a touch jarring, just like Desclos’s book. Her gouache and pastel drawings depicting scenes of bondage and sexual power play are aggressive in subject matter but demure in expression; the larger paintings are more vivid in colour but the figures are further abstracted, giving them a fever dream quality. The push and pull of the works made me wonder if I was being toyed with visually in the same way O was physically. The artist coyly danced around the question of whether she was trying to seduce me with these images, but we talked frankly about sex, power, and the incredible freedom found in erotic imagination.

When did you come across the Story of O?

I was big into reading when I was younger—I still am—and I came across it as a teenager. I vaguely remembered it being banned and highly controversial at one time, so I got a bit of a thrill walking around with it. I’ve read it almost yearly since then.

Really! What about it makes you return to it over and over again?

It was the first book I read that really explored a woman’s inner life and her erotic imagination. That was very compelling to me as a young person. I was looking at the nude figure from an early age, but studying it in a way that was pretty devoid of sexuality. I was 13 when I took my first figure drawing class with my mum. I remember showing up to the first session and the male model suspended from a pole, naked, with his penis hanging, like, six inches from my head. And I remember thinking “wow, that’s a naked man in my face,” but my mom and all these other older women were there, so I just had to get over it. Story of O, however, was what stoked my interest in sex as something desirable, but also as a form of power.

Power and sex are really intertwined, if not entirely the same thing in the book, thoroughly exploring BDSM as it does. Was it difficult visually representing some of its more graphic scenes in a way that adequately expressed the violence between O and her lovers as an exchange of power, rather than a system of abuse and exploitation?

That’s something I was really mindful of. I was reading Andrea Dworkin’s essay, “Woman as Victim,” who talks about Story of O in terms of rape and abuse, and that’s not what this book is about. In the beginning of the story, O is taken to a chateau as a submissive by her lover Rene. At the time she’s kind of a naïve, unformed woman who hasn’t really explored her sexuality or her desires. But she realizes that BDSM is something she’s interested in.

“The interesting thing about fairy tales is that since they were oral, often they were a way for women to talk about desires, fantasies, and sexual issues when they didn’t have the freedom to otherwise.”

The book begins with her consent, and ends with her consent. Every interaction is consensual. I see it as a very sex positive, feminist icon of literature. And many do, including Susan Sontag, who uses it to talk about the difference between art and pornography in “The Pornographic Imagination.” So in my drawings, I wanted O to come across as always self-possessed and I follow her in each scene I chose to depict—I wanted the images to feel like they were constructed from her point of view, not a voyeur’s.

I’m interested in hearing more about what differentiates art from porn, because your drawings, while explicit, are incredibly artful and don’t come across as pornographic at all.

I’m interested in hearing more about what differentiates art from porn, because your drawings, while explicit, are incredibly artful and don’t come across as pornographic at all.

I think it comes down to a really smart use of humour in this book, which I try to play on in my work. Sontag talks about it as meta pornography, and I agree. Declos is clearly in command of all the symbols and clichés she’s using from porn—velvet drapes at the chateau, firelight, stereotypical costumes, whipping in the sex scenes. But she’s playing with the seriousness of them, and shifting the meaning around them. I think she’s using sexuality as a form of intellectual seduction rather than physical.

This isn’t the only book you’ve illustrated though. You crafted the beautiful Tales of the Brothers Grimm with fairy tale scholar Jack Zipes, and you’re working on a book of Madame d’Aulnoy’s proto-feminist fairy tales from the 18th century, to be published by Princeton University Press next year. What interests you in translating literature into something visual?

When I started working with Jack Zipes on the Grimm’s Fairy Tales for the show at the Drawing Center in 2015, I fell in love with drawing from personal experience and my imagination to bring these timeless tales from previous centuries back to life. The interesting thing about fairy tales is that since they were oral, often they were a way for women to talk about desires, fantasies, and sexual issues when they didn’t have the freedom to otherwise. The original stories are highly sexual and violent, and the way women transform in them really bespeaks a kind of power. And so I see O as a kind of modern day fairy tale because she transforms in it. She’s not transformed by desire or sex or trauma, but instead she transforms herself in order to embody all of these things.

So your depictions of these violent, sexual tales draw on the stories themselves, but also your personal experiences and imaginings? Is it difficult to infuse yourself in these narratives, or is it somehow freeing?

It’s absolutely freeing. So much of my work is about taking on roles like an actor would and being a voyeur in different situations. For the last series of paintings I did before this, “Dancers and Dominas,” I actually went into sex dungeons and photographed dominatrixes and submissives and worked from the images I took. This is a similar project, but the scenes are based on what’s in my mind’s eye when I read the story, which is created from my imagination and my own desire, which is liberating because I’m not basing them on anything grounded in real life. And the freedom for Declos to have written this story in the 1950s, to express herself and to illustrate that women can desire both submission and domination and everything in between, is incredibly empowering, which is something I felt when drawing Story of O.

Photography © Don Stahl