Elephant writer Bella Butler offers 5 must-sees at the annual photography festival in the french city of Arles.

One of the art world’s most prized photography festivals of the year will be up and running in only a couple of days. Le Recontres d’Arles, known as the birth site and hub for emerging and established photographers alike, opens July 1st and will be in full swing until September 29th. This festival serves not only as a platform for artists, but also for the remembrance of the history of the medium itself, a medium which was not always considered a ‘serious’ or ‘major’ form of art. A unique feature of the festival is that it is intrinsically woven into the city of Arles itself; its 40 exhibitions are scattered throughout the city, inhabiting a range of spaces, from 12th-century chapels and cloisters to 19th century industrial buildings.

This year’s lineup is impressively diverse, both in its community of photographers as well as in the depth of themes and styles of the work. Elephant’s 5 picks range from wide-angle dystopian landscapes to close-ups of the intimate minutiae of personal life.

We dive right in with Mo Yi: Me in My Landscape at La Mécanique Générale,a series of from the auto-didact Chinese artist Mo Yi (莫毅). Mo Yi’s images from the streets of China are energetic and bracing. With their energy and motion-filled shots, they transport the viewer, forcing an embodiment. Mo Yi is also radical in his approach to the medium, in that he takes most of his images without looking through the viewfinder; through various methods—such as fixing the camera to a stick—the classical human “gaze” is overturned and assumes a multitude of positions and its own autonomy. In the photo below, the gaze lies close to the ground, provoking a visceral feeling of chaos, of being-in-the-fray of the city. There is no space between the physical camera and the society it is capturing. Mo Yi: Me in My Landscape is a must see and will meet your expectations by turning them on their head.

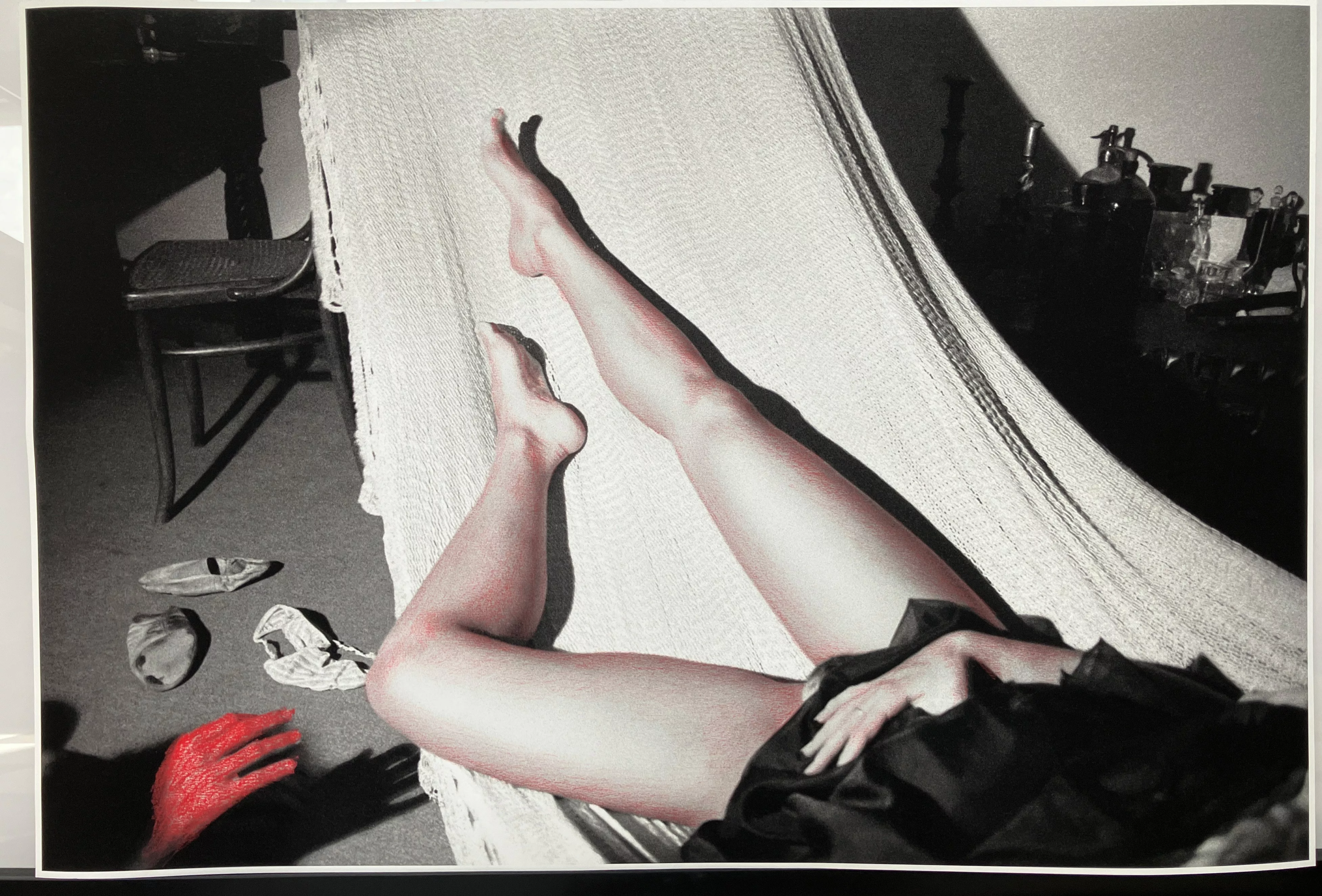

In a study of the potency of stillness as a contrast to Mo Yi’s energy, Ishiuchi Miyako’s exhibit Belongings in Salle Henri-Comte—including works from Mother’s, ひろしま/hiroshima and Frida—presents us with emotionally charged photos of Miyako’s late mother’s belongings. A battered and open lipstick, tattered leather gloves, and pink boots with scuffed heels, are all examples of the mundane but personal ephemera of a human life. Miyako writes in her entry for the festival, “My mother and I did not get along too well when she was alive, but as I shot her belongings, it seemed that the distance between us gradually lessened. Each of the things that directly touched my mother were like part of her skin, and I came to vicariously sense these parts of her body.” Indeed, Miyako’s works evoke touch and connection that draw the viewer’s nose right up against the image, until one can go no further. In a world where everything is political, these photos show the dual significance of turning inward, of looking at one’s own life right in the eye.

What does it mean to visually connect to someone we have lost? In Miyako’s words, “to take a photo is to gauge one’s distance from the subject, and to render visible the unseen things that lie beneath the surface. How could I capture images beyond the reach of my eyes?”

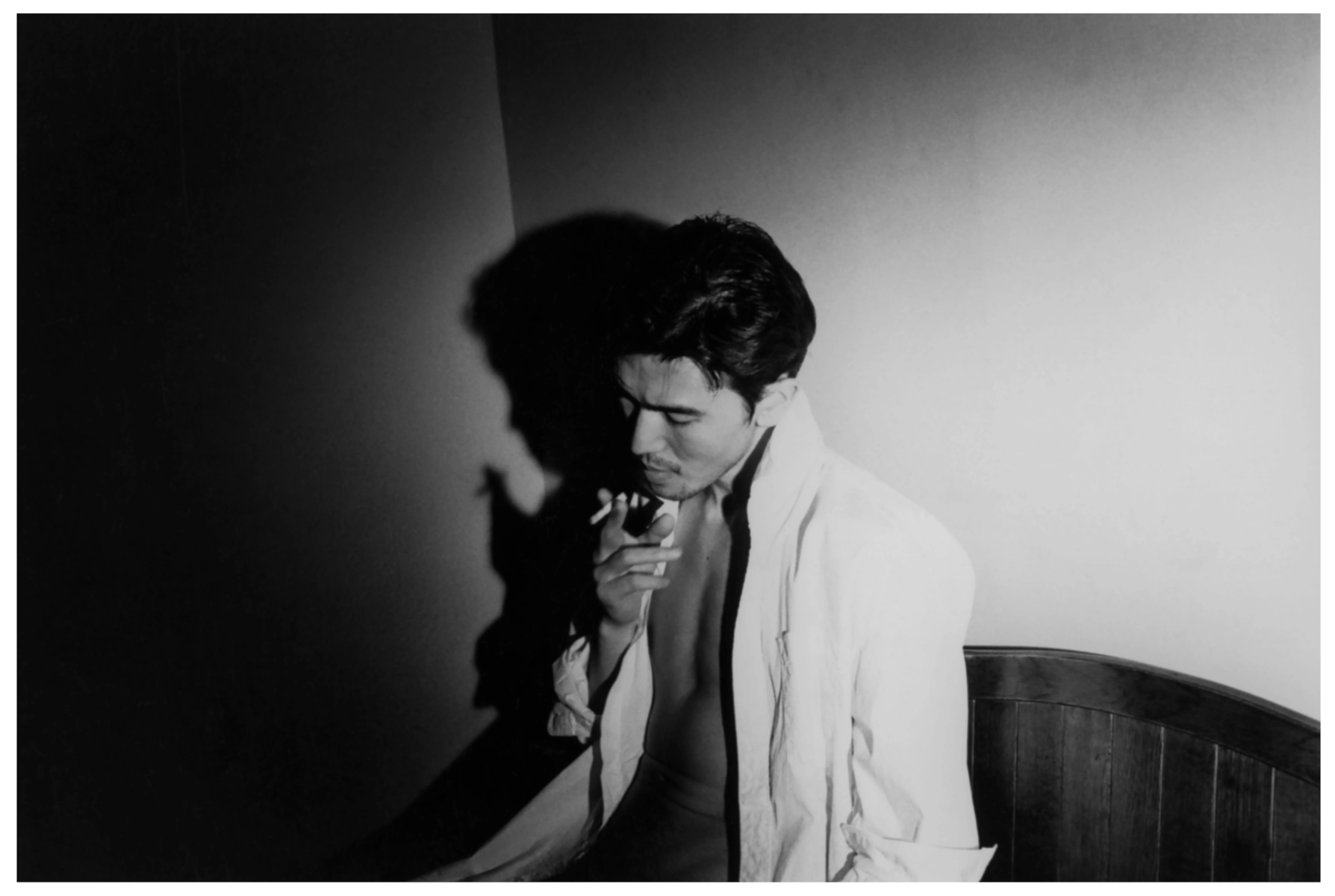

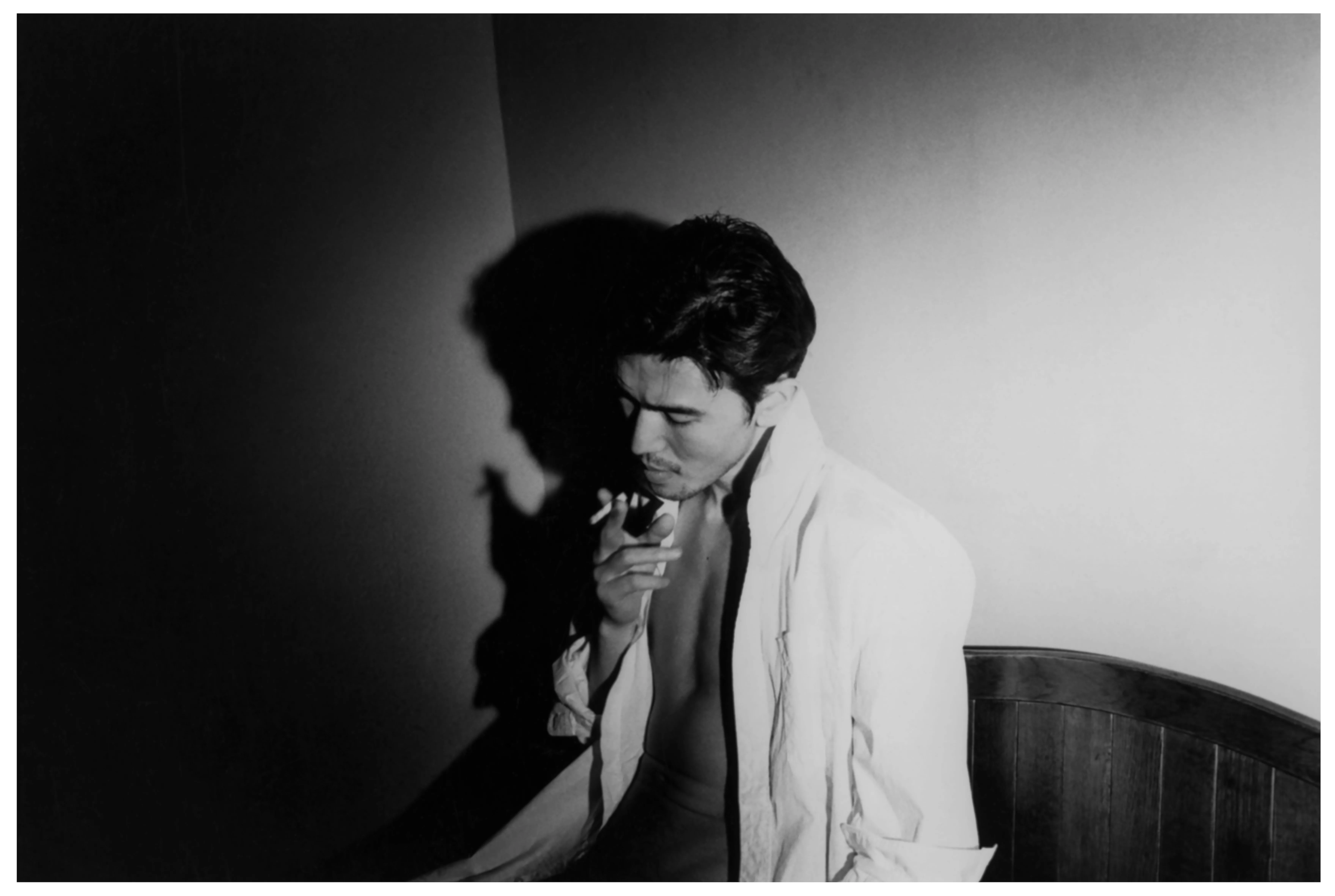

In a departure from the merely mortal, Vampires Fear No Looking Glass: El Grup de Cali, Vampirism and Tropical Goth at Eglise des Trinitaires, consists of uncanny and bodily images that center around the ‘El Grupo de Cali,’ a creative and socially rebellious gang active in the 1970s and 1980s in Cali, Colombia. This show is the first time that this network of artists—spanning from the mid 20th century to the early 21st century—will be exhibited together.

Their photos capture visual aesthetics—Vampirism and Tropical Goth—that are ultimately responses to certain socio-political climates. As explained by the curators of the show, “Vampirism is a mode of group interaction in which everyone is a source and sucker of energy. Tropical Goth—a dark, skeptical, cynical, even monstrous perspective on life, is derived from these artists’ disruptive analyses of the conflictual social and cultural structures of the conservative, provincial city of Cali and Colombia more broadly.” Using the tools that photography has to offer, the ability to transform perception and perspective, this group of photographers have created compositions that are as heart-felt as they are bone-chilling. They seem to be saying that to explore humanness, sometimes we need to grasp monstrosity.

In the spirit of addressing historical gaps, this year Aperture, a cornerstone of the photography world, is putting on I’m So Happy You Are Here at Palais de L’Archevêché, a collection of works by over 25 different Japanese female photographers from the 1950s to today. The content is broad, but rich; there are black and white prints that capture political tumult from artist Watanabe Hitomi as well as colorfully abstract compositions including cutouts and objects from Yamazawa Eiko.

To have the opportunity to see so many Japanese female artists from so many different generations, all gathered under one roof, is a rare opportunity and shouldn’t be missed. These photos, such as Kawauchi Rinko’s impossibly delicate close-up of eyelashes and a single strand of hair, invites the viewer into the human- micro as well as a macro- narrative. Aperture’s exhibition will be one of visual conversation across time, artists, and viewers in the present.

Last, but certainly not least, is a body of work by Nanténé Traoré included in the festival’s exhibition series Emergences at Espace Monoprix, which spotlights 11 new artists, all of whom are contenders for the 2024 Discovery Award Louis Roederer—a financial award given to support emerging artists.

Traoré’s dreamy, yet tension-ridden, series is titled L’Inquiétude [Disquiet]. This “dis” and the “quiet” of the title are ideologically reflected in the contradiction present in the work. They at once convey a tailored sense of nostalgia while also conveying signs of the unavoidable: the present. The appliances, the technology, and the youth portrayed in Traoré’s images situate them in time but undoubtedly insist upon their own timelessness: the trope of the contemplative youth, the innocent yet sexual being, or the unattended bouquet of flowers linger and return in the mind of the viewer like an old memory.

Here you can find a map of all the exhibitions. The exhibitions will be up from July 1st until September 29th, 2024.

Words by Bella Butler