Dating back to its earliest depictions in Western art, the nude has always been confronting. The way artists have portrayed bodies, and who they have portrayed them for, has always reflected back moral, social and sexual attitudes of the time, from Goya’s life-size, “profane” Maja Desnuda to Manet’s Olympia and, just a year later, Courbet’s explosive Origine Du Monde.

Women were the first to challenge the inherited hegemony of the nude and the gaze. Victorine Meurent’s defiant look as she assumed the role of Olympia in Manet’s masterpiece made the painting incredibly radical at the time. With the introduction of photography, the possibilities for what a nude could express were expanded further: Germaine Krull’s gaze on the naked female body, intended for a female viewer, in her 1930 Etudes de Nu, remains a pivotal moment in the history of nude art; her naked bodies were still erotically charged, but on her own terms, an ode to form and beauty, vulnerability and weakness, and also strength and self-empowerment.

Today, nudes no longer have to be synonymous with the cis, white, heterosexual experience. Two exhibitions this month—Exposed: The Naked Portrait at The Laing Art Gallery in Newcastle

and Curiosa at Paris Photo—investigate the nude according to these new perspectives. At the Laing, an eye is cast back to reframe history and tell the story of how certain artists have always looked differently at bodies, while in Paris, the camera’s complicity with the erotic is called into question, in the context of the #MeToo

movement.

These seven artworks narrate a new idea of bodies as power dynamics shift; nudes are no less explosive, but far more elastic in meaning.

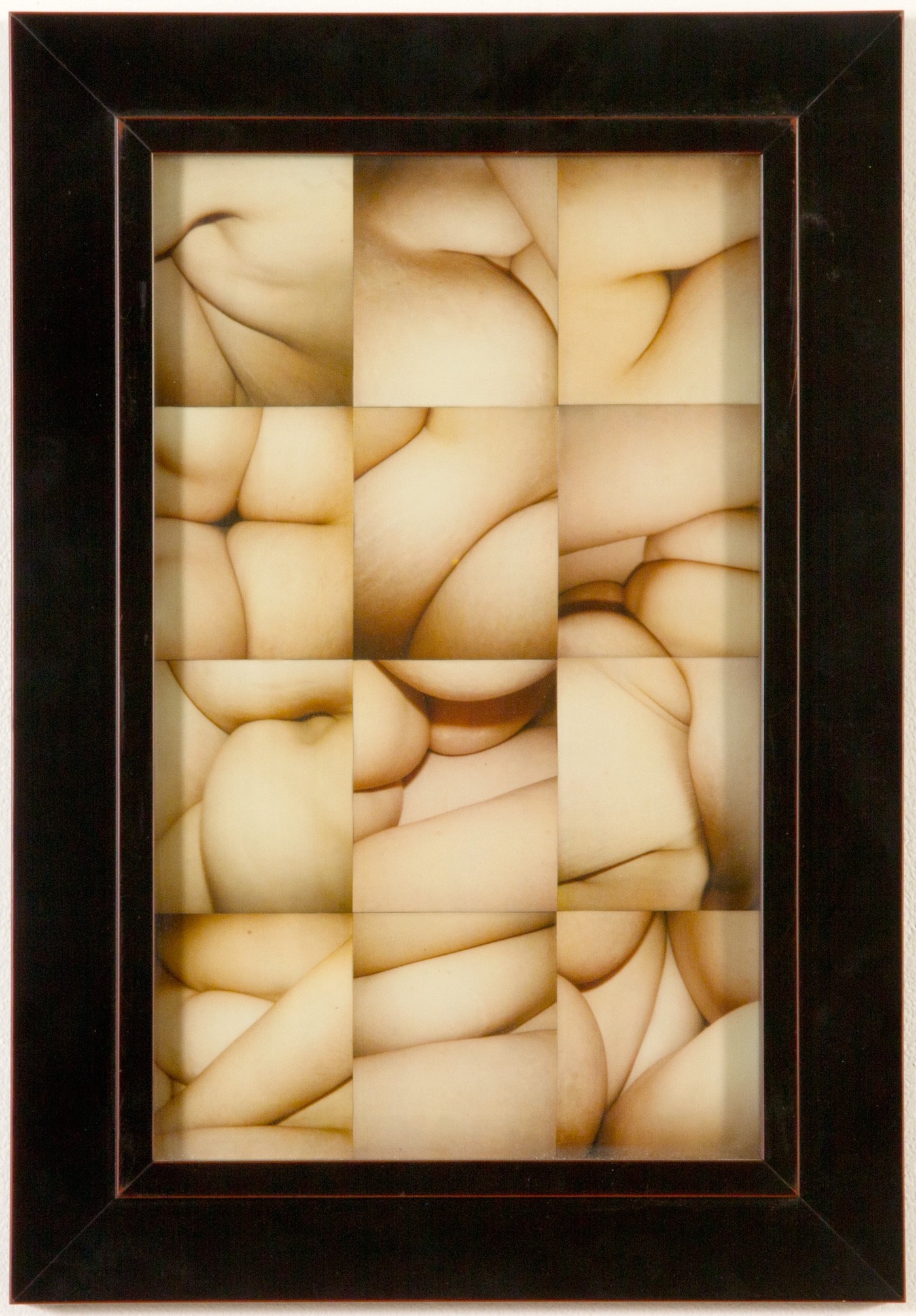

Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, Amnion Folds Study, 2002

Traditionally, a nude has meant a naked body, which is very often female. Genesis P-Orridge’s Pandrogeny project began in the 1990s, as an attempt to become one body with the artist’s life partner, through over 200,000 USD worth of body modifications, so they could resemble each other and live as if a single entity. “We started out, because we were so crazy in love, just wanting to eat each other up, to become each other and become one. And as we did that, we started to see that it was affecting us in ways that we didn’t expect. Really, we were just two parts of one whole; the pandrogyne was the whole and we were each other’s other half,” the artist has said.

© National Portrait Gallery, London

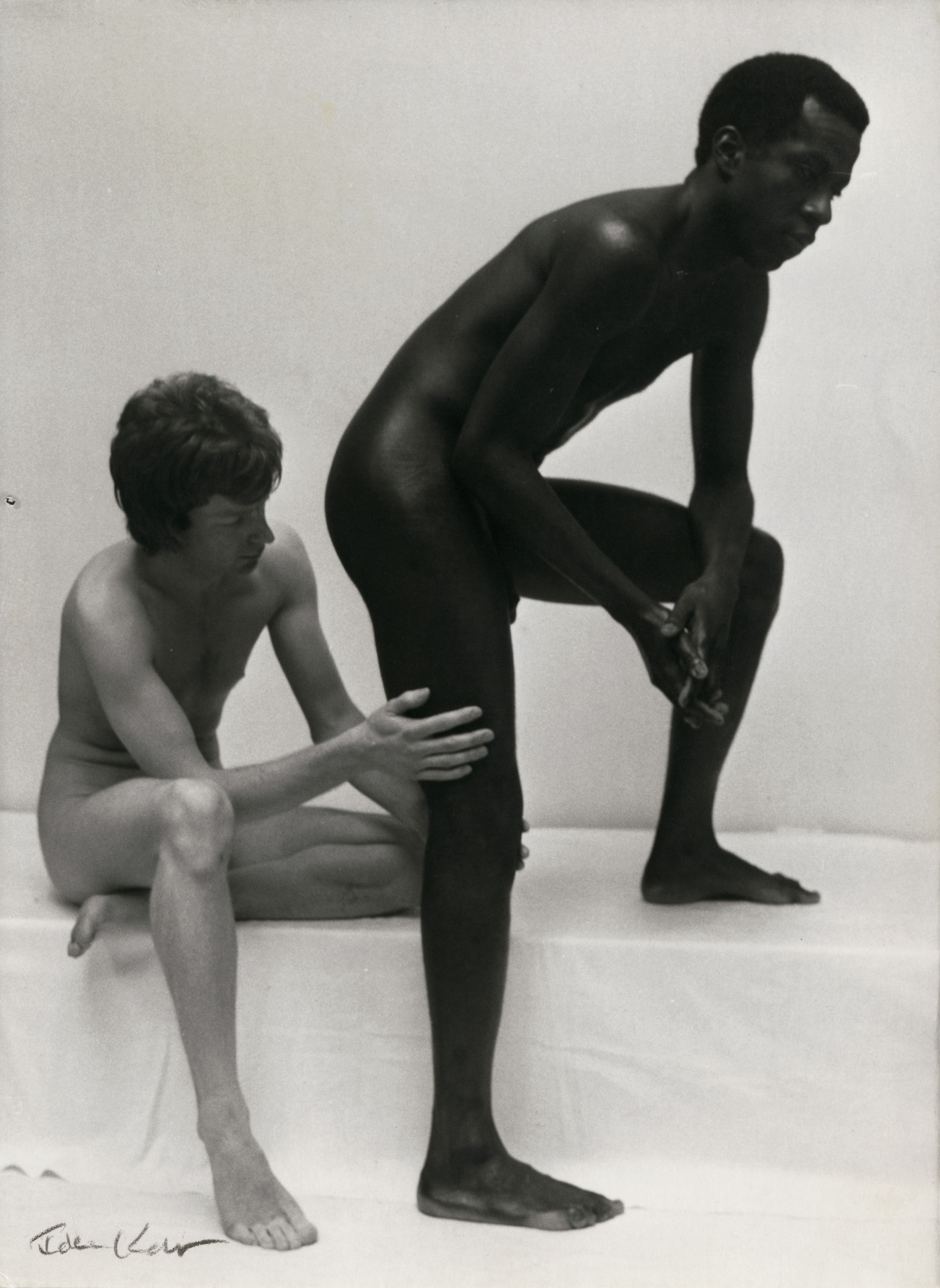

Ida Kar, Richard Victor Grey-Ellis; Anthony Sobers, 1974

The late great Ida Kar is, like many women of her time, little known despite her contributions. The Russian-born avant-garde artist’s sumptuous, rich portrait photographs were groundbreaking in many ways. On show at The Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle, is this nude portrait of Richard Victor Grey-Ellis and the psychologist Anthony Sobers, who posed for several pictures for Kar, shortly before she died in 1974. The relationship between Grey-Ellis and Sobers is ambiguous—it is not known if they were friends, or lovers—but it is a beguiling series that emanates affection, all the better perhaps for its refusal to define its subjects.

Ishbel Myerscough, Ishbel Myerscough; Chantal Joffe (Two Girls), 1991

The British artist Ishbel Myerscough’s portrait of herself and her best friend, the painter Chantal Joffe, who she met at Glasgow School of Art in the 1990s is in dialogue with the history of nude painting, but it so much more: it is about friendship, it is about femininity, it is about imperfection and it is about reclaiming the gaze. It’s also about great earrings.

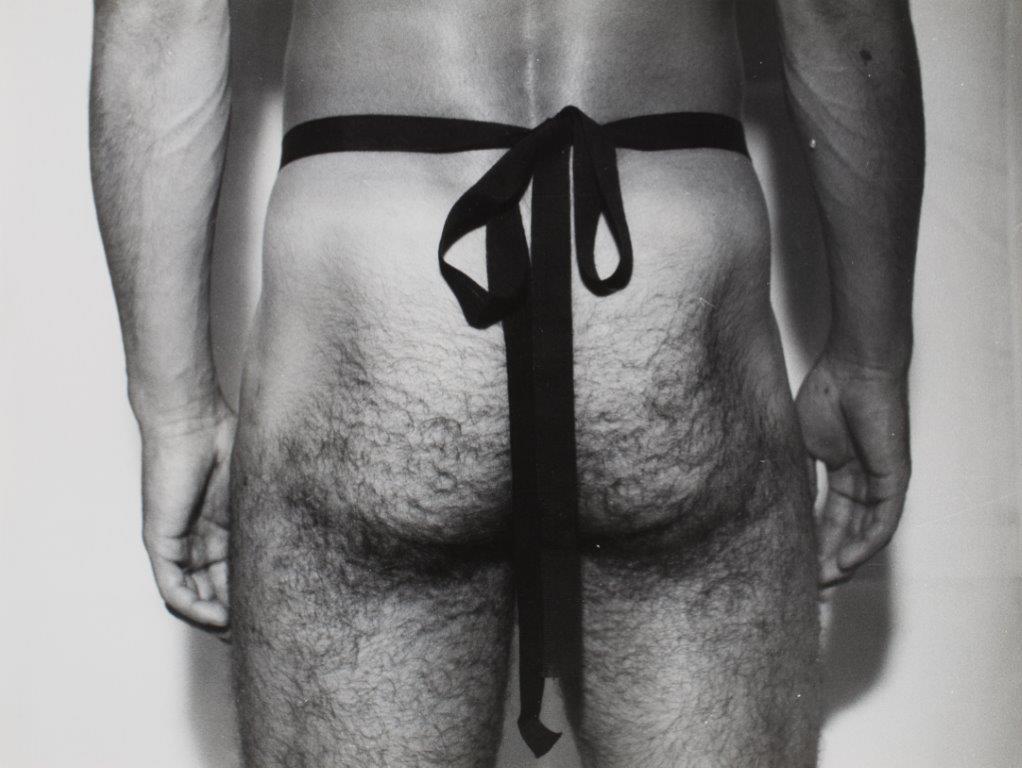

Károly Halász, Promote, Tolerate, Ban I-II, 1978

Men suffer in the patriarchy too. These hirsute male buttocks, bound with a bow, were shot in Hungary in the late seventies by neo-avant-garde artist Károly Halász. In the context of socialism in Hungary in the 1970s, Halász’s existence as a gay man was unavoidably provocative and political. For Halász, art was the only way to express his identity and sexuality in public, while homosexuality was still considered an illness that demanded a cure. This photograph, Promote, Tolerate, Ban, makes a direct political statement: the title refers to the 3T cultural politics of the Kádár-era, in which homoeroticism was prohibited and had to be hidden.

Jo Ann Callis, Untitled from Early Color Portfolio, 1976

Until recently, few people had encountered the work of Jo Ann Callis, who made her surprising and striking Early Color series in Los Angeles over forty years ago at her home. It remained undiscovered until it was shown for the first time in 2014 at Road Gallery in Santa Monica, with a publication released by Aperture the same year. Sensual and evocative, Callis used suggestive materials (silk, leather, duct tape, string) with the banal and the domestic. Her vision of female bodies—at the height of the women’s rights movements in the West—was dramatically different to anything around at the time. Callis didn’t intend them to be read as political, but their presence articulates many of the concerns of self-representation and pro-sex feminism today.

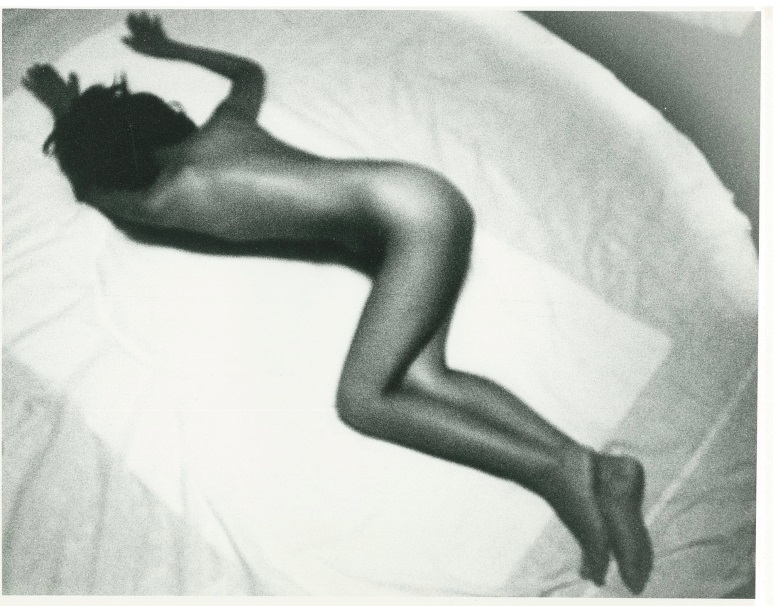

Kenji Ishiguro, A Heartless Room, 1976

First published in 1972, Daido Moriyama’s Mayfly (Kagero) was the only photobook to collect Moriyama’s nudes exclusively, mostly Kinbaku scenes—the now-famous Japanese bondage practice, in which women are tied up with rope. It was a work that visually defined Japanese erotic art and the western idea of Japanese sexuality. In Kenji Ishiguro’s image, shot after Moriyama, there is a more subtle erotic atmosphere; intimate, strange and almost solemn, full of emotion.

Paul Mpagi Sepuy, Mirror Study, 2018

Following the trajectory of American artists such as Robert Mapplethorpe, Paul Mpagi Sepuy’s contemporary aesthetic calls our idea of the erotic into question, starting with our own complex relationship with ourselves, mediated by the camera. Sepuy draws inspiration from both homoerotic culture and classic portraiture, his own studio, and his own reflection. His fragmentary nudes, consciously crafted, speak of broken, fractured masculinity and stereotypes of manhood, and of the artifice in constructing our sexual identity.