A new book, Ravens & Red Lipstick, can be unravelled by its title. Chronicling the multifaceted developments of Japanese photography, “ravens” alludes to the mournful black-and-white images create by Fukase Masahisa in the 1970s in the wake of his divorce. He became infatuated with the sinister birds and created a groundbreaking body of work that redefined what photography could look like. Meanwhile “lipstick” references Ishiuchi Miyako’s luscious full-colour shots of her recently deceased mother’s lipstick collection, created as a form of commemoration. Ishiuchi was the only female photographer in Japan to gain widespread recognition for her work during the 1970s, when it was still very much a man’s game.

Although both Fukase and Ishiuchi were part of the “new photo revolution”, this survey is not limited to the infamous image-makers who honed their craft during the post-war boom. Author Lena Fritsch, a curator at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, examines the earlier history of reportage that took place during and immediately after the conflict, including Domon Ken and Hayashi Tadahiko’s harrowing images of urban devastation and suffering. She also takes in some of the more recent photography movements that have redefined not only the act of taking a picture, but issues of gender, intimacy and the gaze. These include the “Girls’ Photography” genre of the 1990s and newer practitioners such as Tokyo Rumando, who has been heralded among a younger generation of female Japanese photographers who examine the gaze.

While this book follows a rough chronology, plenty of the featured photographers have been working for decades. For example, Morimura Yasumasa, who has been producing photo works that re-appropriate the canon of European art history and upend gender stereotypes since the eighties, is most heavily represented in the final “contemporary” chapter. Araki Nobuyoshi’s work from the sixties is featured, as well as his experimental overpainted pieces from as recently as last year. His most controversial erotic works are notably absent, and there is little engagement around the question of exploitation, an issue recently raised following high-profile allegations from his former model and muse KaoRi.

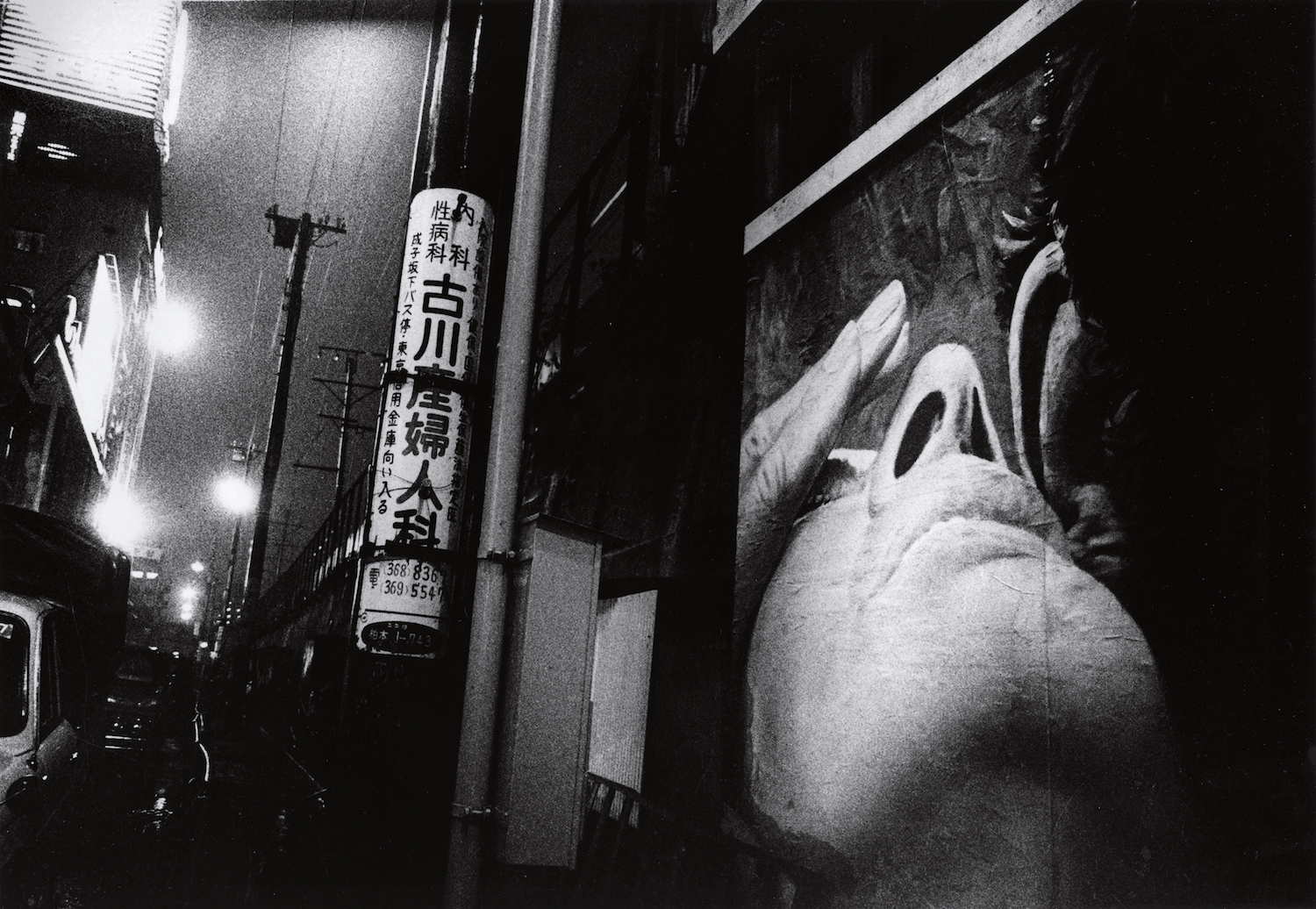

It is clear that Fritsch understands the limitations of presenting a survey based on a particular medium, and her direct address of these constraints is one of the strengths of the book. She also presses the point that she is a non-native, and therefore in some danger of taking a particular “Western” view that might misinterpret the original intent of these Japanese image-makers. As such, each chapter features an introductory essay that places the photographers and their work within a historical context. She charts the eventual appreciation of photography as a fine art form in the seventies, and the significant role of avant-garde magazines such as Provoke, conceived by photography giants Moriyama Daido, Nakahira Takuma and Takanashi Yutaka.

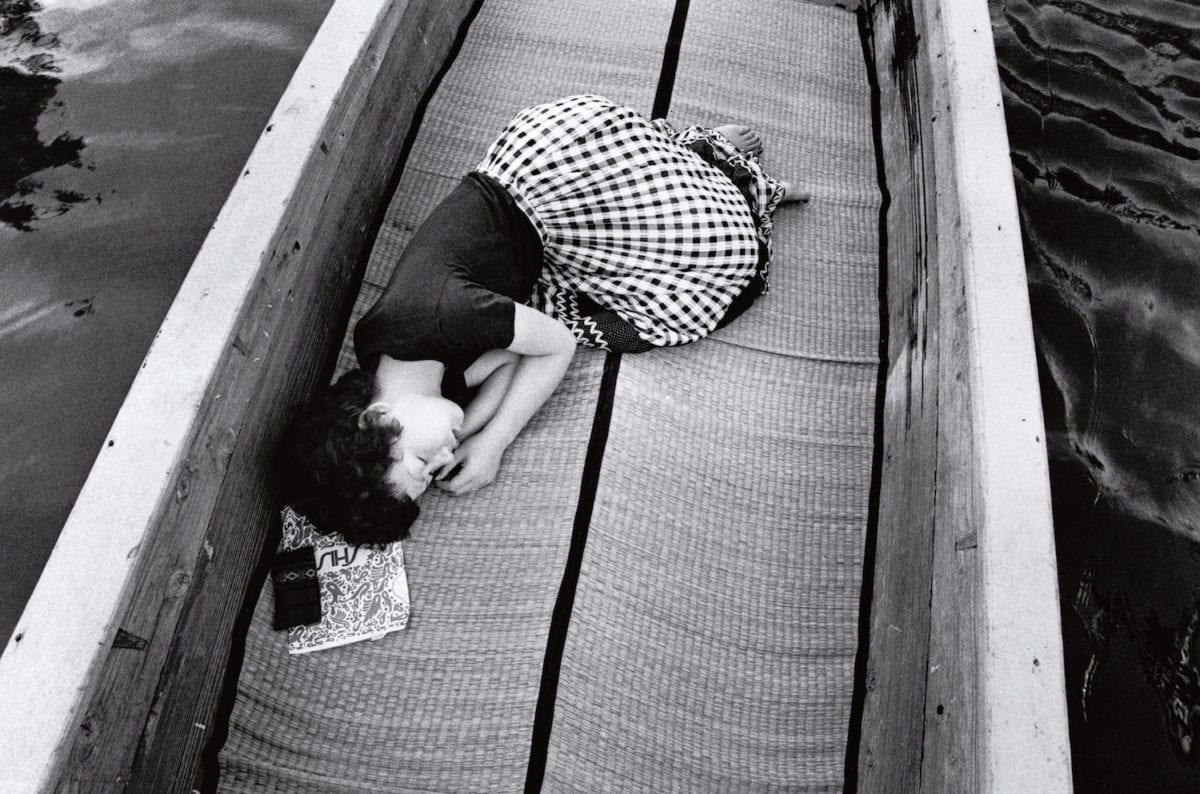

- Left: Ishiuchi Miyako, Mother’s #38, 2002. Courtesy the artist and The Third Gallery Aya, Osaka © Ishiuchi Miyako. Right: Tanuma Takeyoshi, Dancers Resting on the Rooftop of the SKD Theatre, 1949. Courtesy the artist © Tanuma Takeyoshi

The bulk of the texts take the form of an impressive collection of first-hand interviews translated from Japanese. This not only gives space for us to hear from the photographers themselves (many of whom have rarely had their voices published in English) but also allows us to see the incredible connectivity that exists between so many of these photographers, whether it be Ishiuchi alluding to the bad attitudes of some of her male counterparts, or Rumando speaking on the importance of subverting the gaze having worked as a model for Araki.

These accounts are particularly important in the case of the Girls’ Photography movement, which championed the likes of Hiromix, Nagashi Yurie and Ninagawa Mika (all three won the prestigious Kimura Ihei award in 2001). Their joyous, enigmatic images often take the form of self-portraiture or depict other women. These somewhat easily marketable subjects saw the photographers pigeon-holed and put under enormous pressure to conform to their fan base, and each of them explain the hardships they suffered as a result. As Hiromix explains: “The social expectations to be innovative were a huge responsibility, a burden. I suffered badly.”

The interviews also offer a wealth of knowledge concerning each individual’s personal journey and relationship to taking pictures. Every conversation begins with the question, “What inspired you to take up photography?” which, while monotonous, offers a safe model for introducing so many individuals on a level playing field. They range from Suda Issei, who first became obsessed with the concept of looking through an interest in post-war Hollywood movies, to Sawada Tomoko, who was inspired by Cindy Sherman’s portraits and her time studying under the artist Tsubaki Noboru.

Taken together, Ravens & Red Lipstick represents a remarkable cross-section of information, and ultimately allays any reservations over what could be considered a reductive premise—grouping artists solely by their national identity. The compendium of interviews complements the glorious mass of imagery, offering a digestible way to learn more about an individual photographer with a simple flick of the page. This book proves that while any notion of a singular Japanese style or approach is inconceivable, there exists a whole network of connections spanning generations, outlooks and aesthetics. It is a powerful narrative that will only continue to grow.