Elephant writer Bella Butler reviews Print Center New York’s current exhibition ‘Re-Print’ and considers the role of context and conversation within works of art themselves.

When one views a work of contemporary art, hanging on the wall of a gallery, they laud it (and the artist) for its having come into existence. It is a material object of production. It was once nothing and now it is something.

But as we should now well know, the creation of art objects is not isolated to its own creation. In other words, art is not created in a vacuum. Creations exist among/because of/in conversation with/in the context of other creations. In today’s climate, providing context has become increasingly expected of both artists and galleries alike. But for some artists, context appears not in the form of supplementary material, but instead takes a front row seat, establishing itself as the very material and conceptual basis for the art itself.

This seems to be the case with Print Center New York’s current exhibition Re-Print. From the title, viewers are introduced to the “re-ness” of it all, as if to provide a kind of ideological guide to the show itself. The title itself places visitors in a strange temporal state: we are here in the present, viewing the work for the first time, but we are told we are existing in a state of re-ness, in again-ness, in something-came-before-ness.

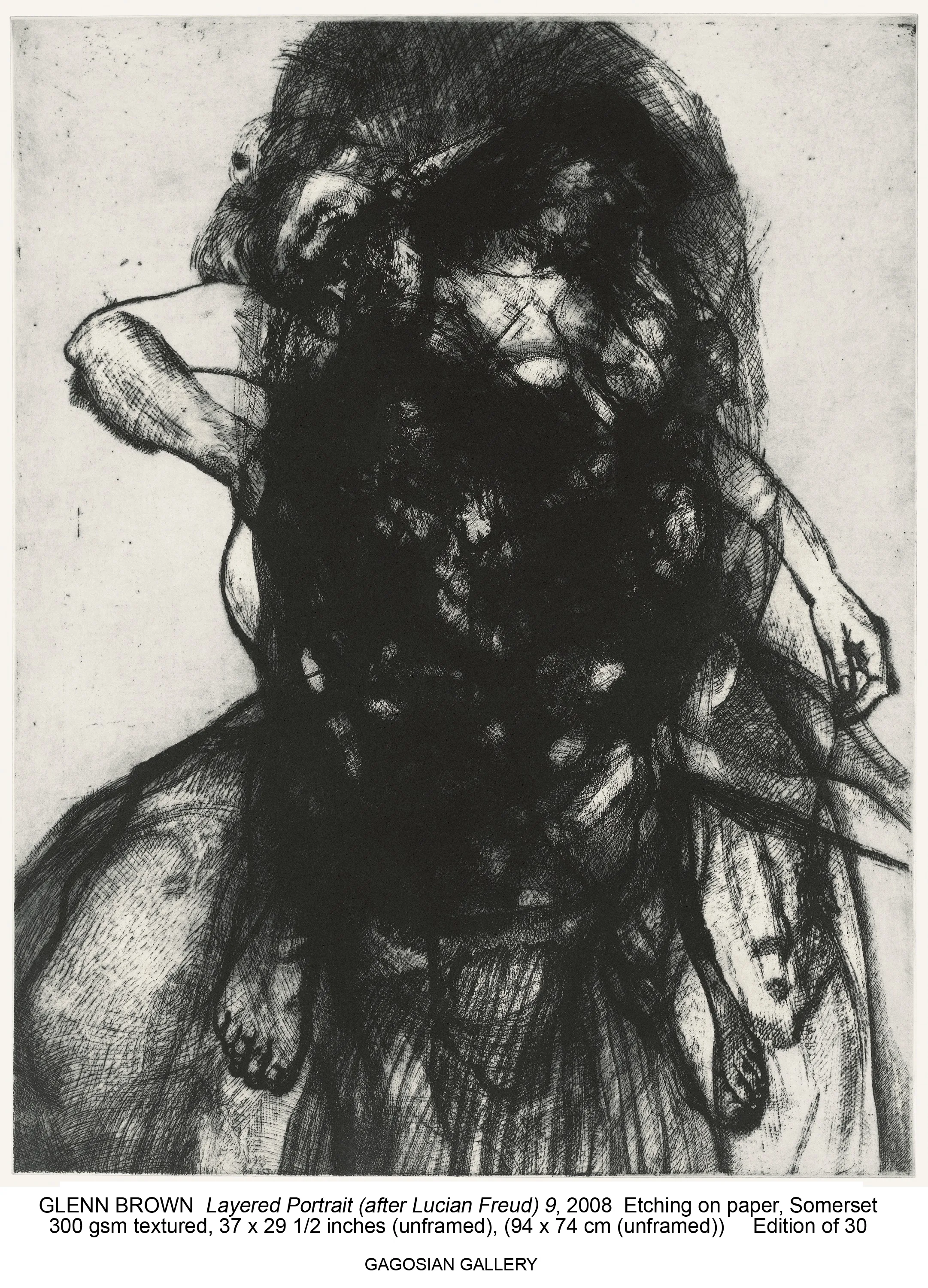

The exhibition showcases five contemporary artists—Mark Bradford, Cecily Brown, Glenn Brown, Enrique Chagoya, and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye—all of whom approach their practices of printmaking in distinct manners. The one thing they have in common, however, is the re-ness of their art, their engagement with the past, both temporally and materially speaking. To further elucidate this for visitors, the exhibition contains archival source material from which each artist worked. For example, alongside British artist Glenn Brown’s Layered Portraits (After Lucian Freud) series—a series of prints which take scans of Lucian Freud prints as the base and are then printed on top of, using the process of etching—the gallery has positioned a couple of Freud’s original prints, which creates a powerful tension, palpable to the viewer.

Brown’s series of Layered Portraits (2008) epitomise the theoretical throughlines of the show, as they provide viewers with a task of re-learning how to see in the context of material re-ness. Brown’s prints provide a peculiar dilemma: we see just enough to know there are many things to see, but the sheer quantity of visual matter to decipher lowers our very capacity to see. Brown flings us into a contradictory state in which we are confronted with a lack of control with regards to our ability to parse out the layers of the the print—what is “re” and what is not—while simultaneously demanding active engagement within the act of seeing, which could hypothetically lead us to re-control our senses and orientation towards the subject matter. As curator of the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinatti Steven Matijicio writes, “indulging in imagery resonates as both a seductive invitation and a damning contract, particularly when directed to/by an artist whose practice hinges upon an ongoing excavation of the image world.” We see Freud’s etchings first, and then must re-see, re-read, re-understand, through Brown’s Layered Portraits that follow.

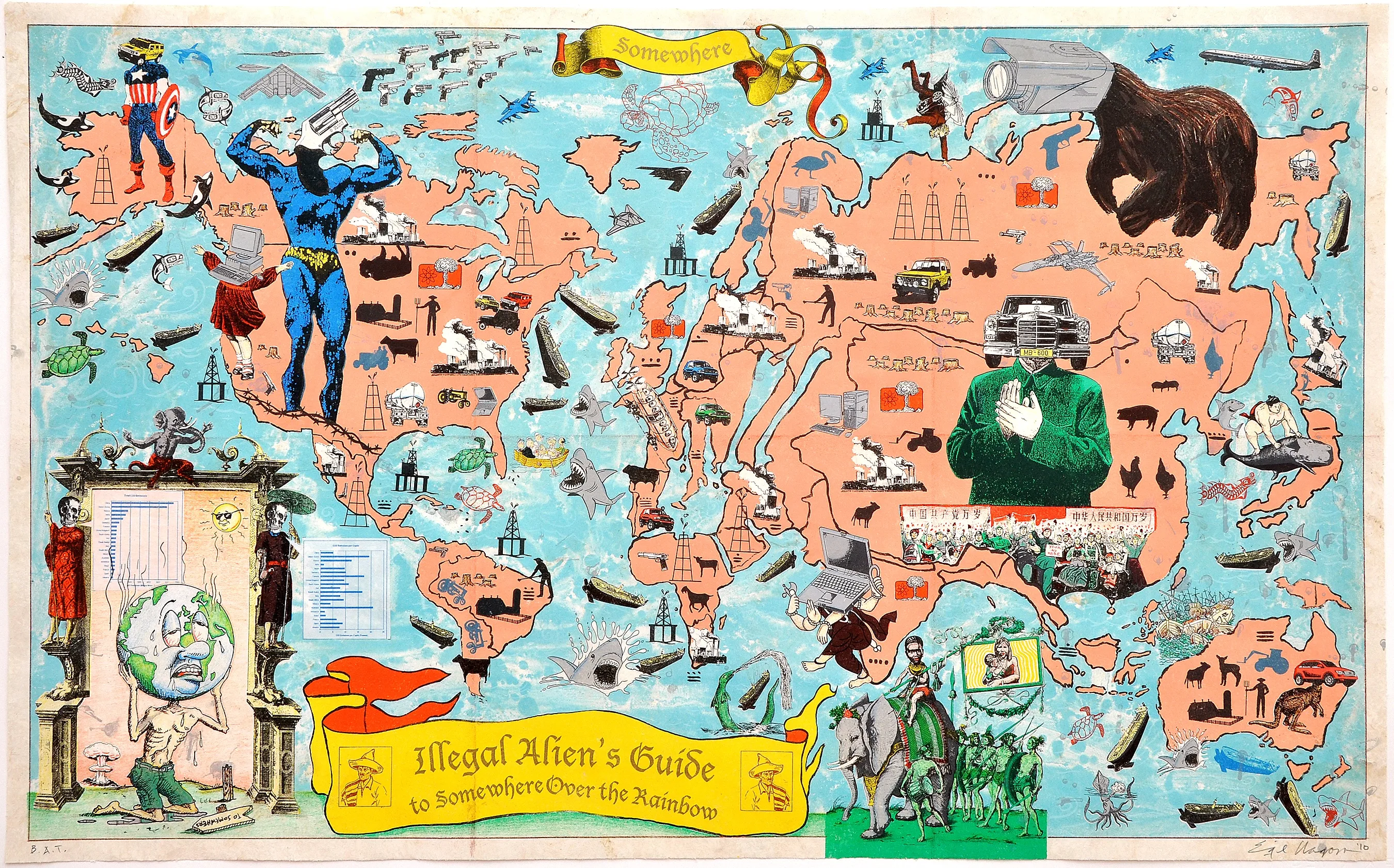

A different approach to the concept of re-seeing is Enrique Chagoya’s El Popol Vuh de la Abuelita del Ahuizote (The Community Book of King Ahuizote’s Granny), 2021, an accordion book which “mimics the codices produced in Mesoamerica before Spanish conquest.” Aside from its impressive composition and apparent mastery of a complex material process, the work radicalises the experience of reading. Even more so than Brown’s etchings, Chagoya’s work foregrounds their relationship to what came before through a kind of collage approach. The use of colours and overlay of characters and text, which use signifiers and imagery running from pre-Columbian mythology to European fantasies of the “New World” to 20th century U.S. popular culture, make the individual components legible as things in themselves as well as things which crash up against each other. In other words, we understand their distinctness, while also acknowledging their undeniable historical connectedness, made clear for us by the artist’s composition.

Additionally, our reading experience is subverted by the instruction on the wall, which tells viewers the book is meant to be read right to left. For readers of the English language, this creates a feeling of moving backward through the narrative, which is juxtaposed with the progressive content and modernity of Chagoya’s work. And better yet, after reading the piece backward, one must move forward in space again in order to reach the next works of art. It is re-reading, upon re-reading, upon re-reading. Under the accordion book, Chagoya has also shared with the gallery his own archival collections from which he drew inspiration from, prompting further historical dialogue. I would also add that the re-ness of Chagoya’s work is hugely augmented by the visible texture and haptic nature of the book, as the book is made from handmade amate, a traditional fig bark paper. One is deeply disappointed to not be able to reach out and touch it, to feel history in its many material layers.

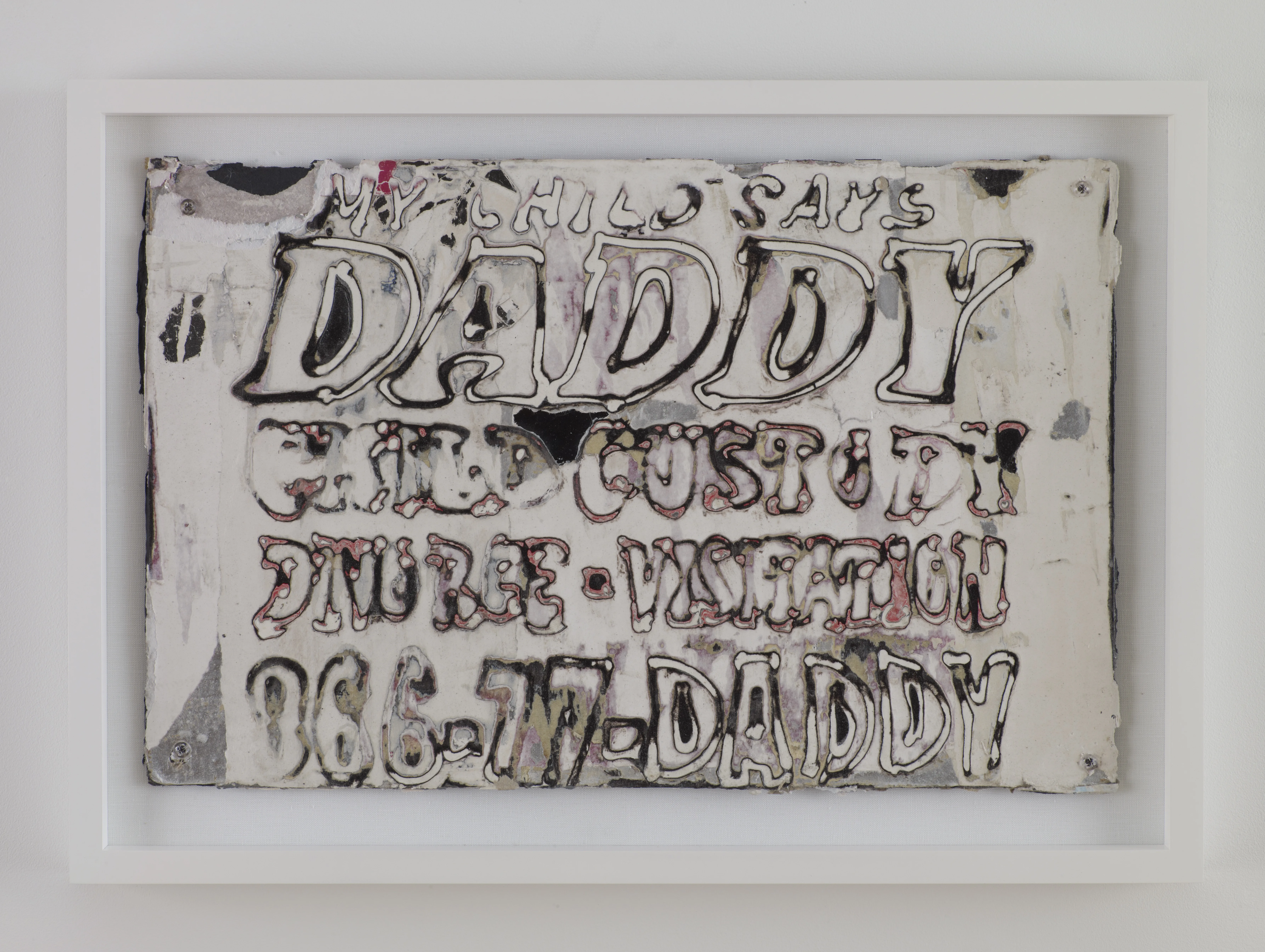

Similarly, implications of hapticity appear in Mark Bradford’s series of 14 etchings and photogravures Untitled, 2012, as they are directly based on “merchant posters” that he has salvaged from telephone poles, construction sites, and shop windows in South Los Angeles. Despite their flatness in the frame, the centre of the print, which holds the texts from the found signs/advertisements, has a three dimensional nature, drawing attention to the ultimate material implications of advertisements to begin with. While advertisements are 2-dimensional in their representational form, their implications play-out in our 3-dimensional life. These effects are in line with Bradford’s intention to explore the social, economic, and racialized components of these targeted advertisements which “target low-income residents in moments of need, offering quick divorce, immigration papers, check cashing and addiction treatment.” By raising these found objects to the status of fine art, we are forced to re-see things we might otherwise overlook, in terms of the political implications of signage and seeing that is forced upon certain civilians in the form of ads.

Other works in the show include Cecily Brown’s etchings from 2004 which are transformations of print satirist and social critic William Hogarth’s engravings from his series A Rake’s Progress (1735) and Four Prints of an Election (1755). The effect of these transformations is almost: relief. What were once engravings that stood fast in the denotation of their era, beautiful but overbearing in their detail, become etchings filled with air and room to breathe. It is as if Brown is saying: you may be able to read more with less. It is another form of re-reading, re-seeing, re-contextualizing modes of representation which came before her.

Last but certainly not least (as these works to follow are actually presented early in the flow of the exhibition), Lynette Yiadom Boaky’s ten etchings of First Flight (2015) are subtle but powerful in theirengagement with the concept of re-ness. The sepia colored portraits of Black men wearing feathered ruff collars explore a serial mode of representation that creates a self-contained yet buzzing energy. The sheer quantity of lines used to make-up the portraits seem to pull the subjects of the paper; it is as if the only thing keeping them on the paper is the frame and the glass. As with the other works in the show, Yiadom-Boakye’s are accompanied by and juxtaposed with historical context: an engraving by the 17th century Flemish artist Anthony Van Dyck. Van Dyck’s engraving creates an obvious dialogue between the European portraiture conventions and their relationship to race. The re-ness exists as a kind of re-claiming of modes of representation, a re-claiming of monopolised ways of seeing.

Words by Bella Butler