The most striking images of Amrita Sher-Gil were taken by her father, Umrao. Garbed in a sari, either staring at the camera with annoyance, or looking coyly away, these images offer us an intimate peek into a life that has been probed by many. As one of India’s most prominent painters, Sher-Gil’s legacy spurred on the formation of South Asian modernism, and was later built upon by groups such as the Bombay Progressives. Fusing her dual heritage into her practice, she took inspiration from both the European modernists and the everyday life that surrounded her in India.

Sher-Gil’s mother and father met through a mutual acquaintance. When Umrao Sher-Gil travelled to London after the death of his father, he met the Indian princess Bamba Duleep-Singh. An interesting figure with a past mired in complication, Duleep-Singh, despite being of royal Indian heritage, had grown up in England—her grandfather was a protegé of Queen Victoria, and her sister highly involved in the Suffragette movement. However, it was not Duleep-Singh that Sher-Gil took a liking to, but her travelling companion—the flame-haired Hungarian singer, Marie Antoinette Gottesmann. In 1912, they were married in Lahore, and the following year their daughter was born.

The couple spent the war years in Hungary. Despite Umrao’s aristocratic background and ties to the British, he was suspected of having made contact with the leaders of the nationalist movement, and found it difficult to return to his home country. Once the family did move, it was to the beautiful hill-station of Simla in Northern India. This was where Sher-Gil began taking formal art lessons, at the age of eight.

“Fusing her dual heritage into her practice, she took inspiration from both the European modernists and the everyday life that surrounded her in India”

Sher-Gil experienced multiple forms of education, discarding that which she saw as too rigid or dictatorial. After Gottesmann enrolled her in a Roman Catholic school in Florence, hoping that this would instil a love of the Italian Renaissance in the budding artist, Sher-Gil rebelled, and insisted on being sent back home to Simla. Here, she joined a convent school, and was promptly expelled for her atheist beliefs. Despite the fact that she despised her brief sojourn in Florence, she later credited the experience as the beginning of a love affair with European art.

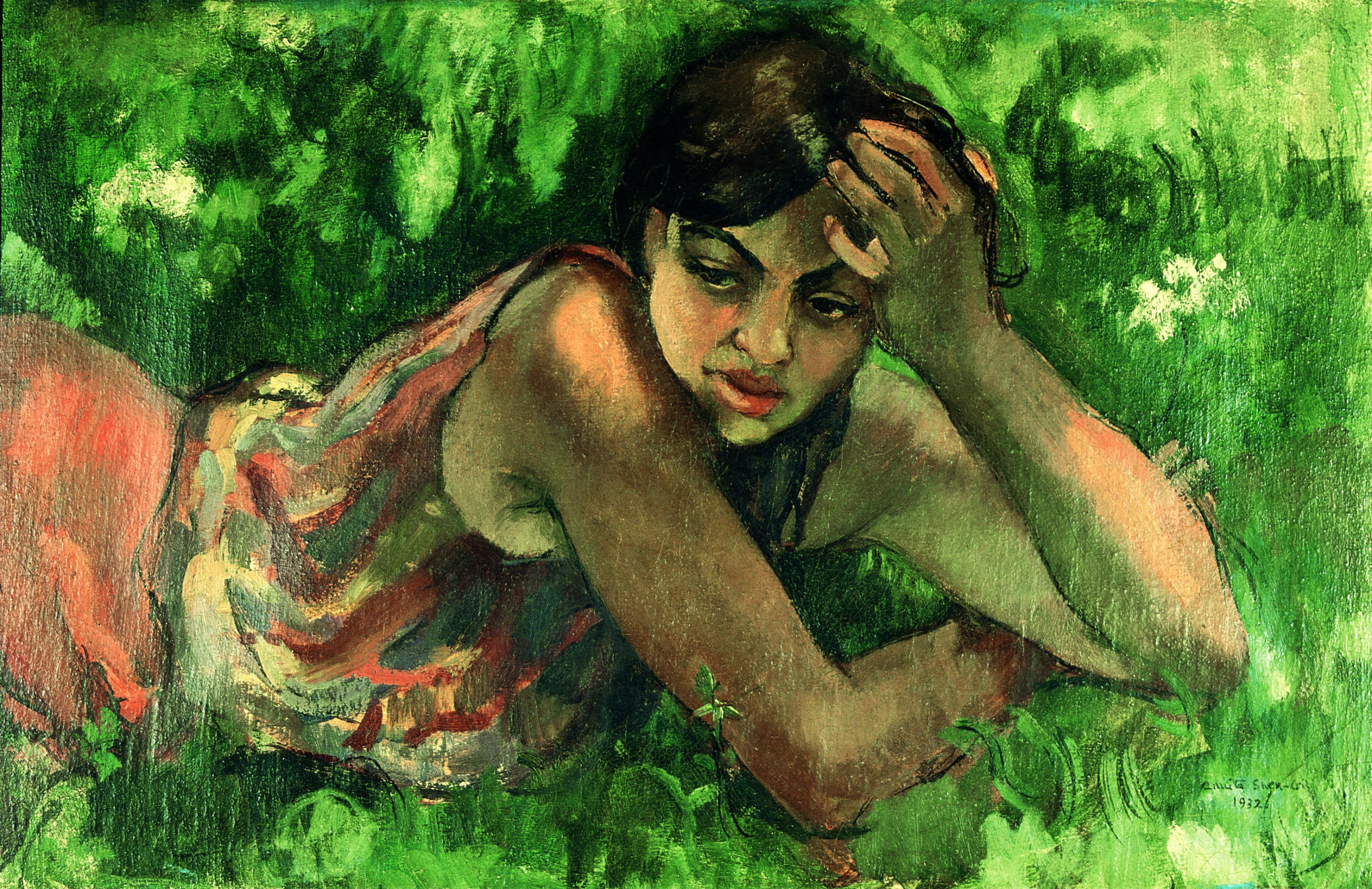

She began to train at home, immersed in the Persian poetry her father was translating, and surrounded by the rural beauty of the countryside. In 1929, the entire Sher-Gil family moved to Paris so Amrita could study art at the Grande Chaumière Academy, under the watchful eye of Pierre Valliant. Her work progressed from classical life portraits which flirted with post-impressionism, into a pared down style that preceded an identity crisis, inspiring her return to India. Of this move, she explained that, “Towards the end of 1933, I began to be haunted by an intense longing to return to India, feeling in some strange inexplicable way that there lay my destiny as a painter.” The institution undoubtedly served her well, and it was this period in time that solidified the fusion of cultures collected on her travels, which manifested into the iconic works of art that are still revered today.

- Left: Amrita Sher-Gil wearing a sari, Simla, India c.1936. Right: Amrita at her easel, Simla, India, 1937. Photos courtesy of Umrao Singh Sher-Gil & PHOTOINK

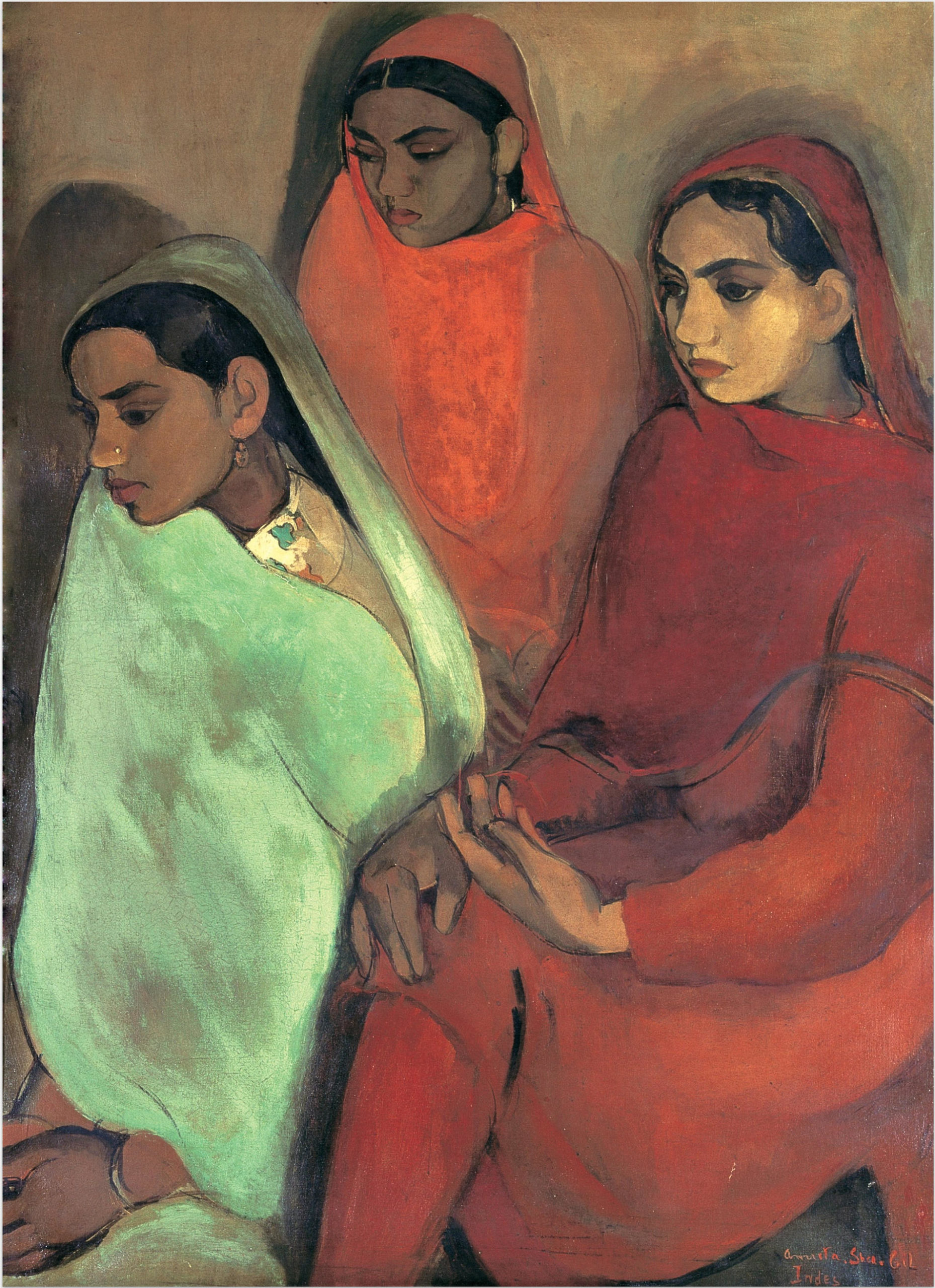

Sher-Gil’s fascination with European style and Indian subject matter began to merge, reminiscent of the visual languages of the Bengal School, but evolving into a cohesive, romantic aesthetic. Her gaze was increasingly focused upon South Asian femininity—works such as Three Women and Group de Trois Femmes depict Indian women with a melancholic beauty that Sher-Gil saw reflected within herself. This fierce fascination has been the subject of many art theorists, who have since called Sher-Gil’s sexuality into question. Frequently depicting various lovers on her canvases, with the same fervour despite their gender, the artist’s queerness was rumoured to have taken the shape of an affair with a roommate, Marie Louise Chassanay, when in Paris. Upon being confronted by her mother via letter, she denied the relationship with Chassany, instead proclaiming that “I thought I would start a relationship with a woman when the opportunity arises.”

She later nurtured a relationship with the pianist Edith Lang. Yashodhara Dalmia, one of Sher-Gil’s biographers, wrote that she was drawn to the idea of a queer affair “partly as a result of her larger view of woman as a strong individual, liberated from the artifice of convention.” Her portrayal of women upended the patriarchal art world, not only because she held a paintbrush as the producer rather than subject, but because she resonated with the experiences being depicted on the canvas. In one work, Self Portrait as a Tahitian, she subverts Gauguin’s exoticising of his subjects by depicting herself through this lens, a deft comment on the male artist’s arguably sexist relationship to women.

“Her portrayal of women upended the patriarchal art world”

The posthumous fascination with Sher-Gil has grown due to the intrigue and allure of her love life. She was unabashed in her enchantment with the various lovers she took, who each make appearances in her canvases. In 1938, she married her cousin, Victor Egan, only to reveal shortly after that she was pregnant. It seemed that this marriage was a plea for safety—they had been close in their youth, and true to form, Egan, who was a doctor, arranged for an abortion. Their marriage seems to have been one of convenience—his satisfying salary enabled her painting prowess to evolve, although her obligation to follow him around according to his army doctor schedule frustrated her independent spirit.

Amrita Sher-Gil, Group of Three Girls, 1935. Oil on Canvas

Before her first significant art show in Lahore, Sher-Gil became gravely ill. This was believed to be because of a second, botched abortion, performed by Egan. As with her life, rumours swarmed around the possible cause of her death, ranging from conspiracy, to natural illness, to a jealous, murderous Egan happening on one of her affairs. Life, rich and full as it was, slipped from her body on 5 December, 1941.

While Sher-Gil’s legacy is unparalleled, it is important to remember that her aristocratic roots enabled pursuit of art as a young woman. This position of privilege resulted in a determination to uplift the poor communities of India through her paintings. While out of this desire she may have produced the most exquisite work, the question must be asked: how many other Sher-Gils languish within India, a country of burgeoning inequity, without the money or resources to realise their dream?