Since I moved away from my childhood home, cooking has been how I navigate new relationships and new places. By preparing a dish, I attempt to constrain the unfamiliar within the act of cooking.

However, it took me a long time to make the connection between cooking and writing. Recording recipes became the first writing that I did for myself rather than for educational institutions or for editors. For a long time I hid in academic formality or the in branded tone of whatever chilly fashion section I was writing for.

I was afraid of becoming visible in language. I had never been a diary keeper and I did not know how to enter into the text. Trying to write ‘I’ felt like trying to jump from a high diving board; ‘I’ felt like a physical risk. What is more, I soon realised that there is no stable self behind the ‘I’ to simply convey into language.

Producing a representation of oneself in language is a process of making, and making again differently. Like cooking and eating dinner, representing yourself in language is a task that is not final until it really is. Both of these things need to be performed every day, and are never the same.

Instead of writing myself into language, I cooked as a means of ‘speaking’ in my own voice for my housemates. Making dishes was how I expressed my moods, affinities, appetites. Meals could be extensive and elaborate, like mango and chilli salad with spiced lamb and rice. If I was tired and depressed, meals were minimal sustenance: almost-mouldy bread trimmed and made into toast, boiled frozen peas and an egg in a bowl.

“Recording recipes became the first writing that I did for myself”

But a dish once eaten cannot be eaten again. There needs to be a recipe, which is to both a document of the event of a dish’s creation, and a suggestion for how it might be made once again, in a different moment.

Recipes look backwards and forwards at the same time. I suddenly wanted to leave a message for those I left behind after moving house, a trace of the meals we had shared and instructions to make it for themselves if they wished to. Writing down recipes was how I said “I still love you”.

I began to write recipes on a blog in late 2011 and shared it with a few former housemates. It was the beginning of writing in my own voice, a first diary noting down ingredient lists, instructions, a little context.

The blog wasn’t originally public, but after friends began to share it with other people, I made it so anyone who came across it could use a recipe if they wanted. After a few months, I was astonished to see the extent of my own work in the kitchen. I had a record of decisions I made, the compositional practice that constitutes meal-making. I had a marker of the time I had spent with other people, attempting to meet both their desires and my own.

I needed this evidence of activity. I was depressed and anxious, and beset with constant dread. I struggled to get out of bed, to get off the sofa, to leave the house. I was failing at my PhD, too paralysed with anxiety to write a word for weeks on end and too scared to communicate that fact to my university supervisors.

“A dish once eaten cannot be eaten again. There needs to be a recipe to both document a dish’s creation, and suggest how it might be made again”

But the slowly growing archive of recipes helped. Eventually I began to think about what it meant to write recipes more closely. My PhD was about a radical German rewriting of the Odyssey that placed traditional ‘women’s work’ at the centre of things. I began to wonder why I had separated the intellectual and domestic aspects of my life. I gave the process of writing recipes the critical attention I had previously reserved for academic study.

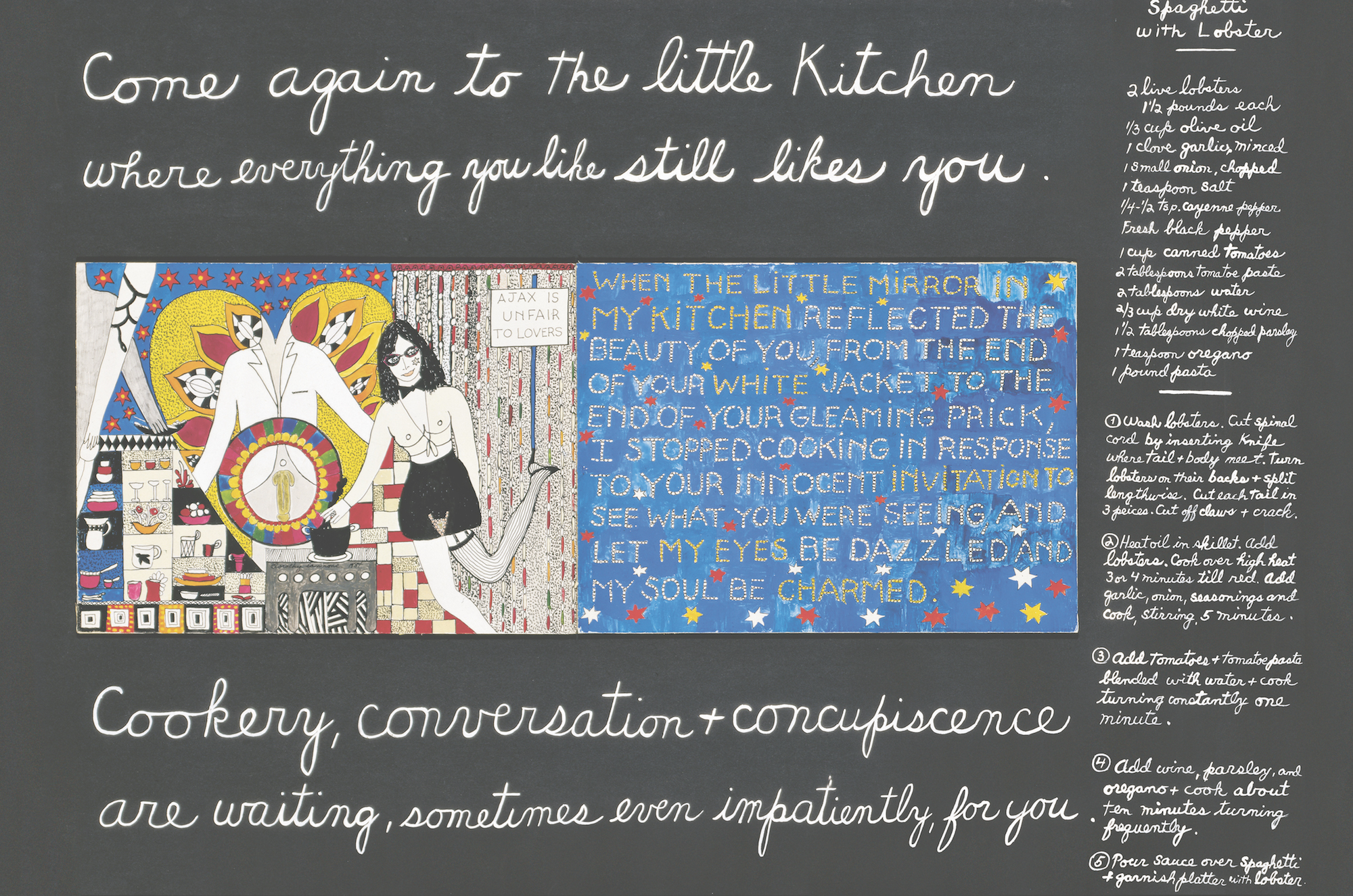

The kitchen became a place where I could experiment with a written voice, with studied thought, with cooking as performance. Taking the recipe out of a purely domestic space exposed the multivalent potency of the form, the many starting points and uses for recipe texts.

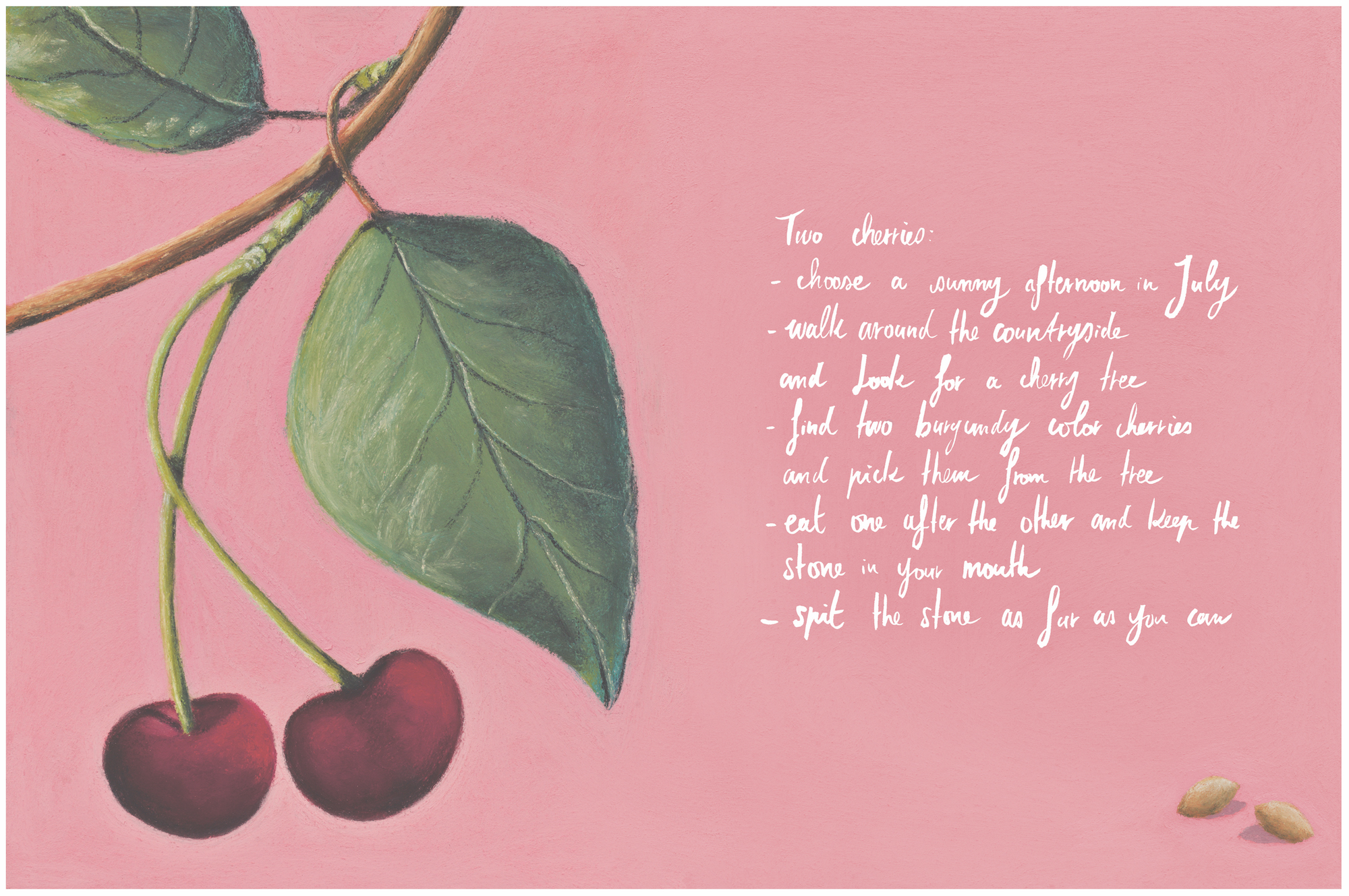

It is a thread that runs through The Kitchen Studio: Culinary Creations by Artists, a new book in which visual artists write down their own recipes. Both a recipe book and an art book, it casts light on artists as workers with bodies that need pleasure and sustenance, while also providing practical recipes. Many bring their artistic practice to the activity of recipe writing, as a form of autobiography, venturing towards the speculative, or as an explicitly political text. Contributors document their cooking and play with the very concept of the recipe in a dizzying range of visual and textual styles, from sketches to phone pictures to handwritten notes.

“It casts light on artists as workers with bodies that need pleasure and sustenance, while also providing practical recipes”

Greek-British artist Athanasios Argianas gives a recipe for making a clay roof tile, with a pencil drawing of how he shapes the tile on his thigh, before giving directions for roasting a fish on the tile. He describes how the tile absorbs the fish’s fat and disperses it, forming a micro-oven to keep the fish moist and the temperature even. The tile is then discarded.

Argianas tells us that the recipe is “a fictional adaptation” from one he found in his grandmother Maria’s cookbook. He never met her, but the cookbook “generated so much in my imagination as a child.” Maria’s recipe is the site for inter-subjective encounters across time: the thighs that have shaped tiles since Roman antiquity, Argianas’ grandmother’s knowledge, the appetites of the present, and the ceremony of eating a whole fish.

The power of the recipe as a political act is explored by Cooking Sections, the Turner Prize-nominated artist duo Daniel Fernández Pascual and Alon Schwabe, with ‘Recipe to Remove Farmed Salmon from an Art Institution’. Their ‘recipe’ for excluding farmed salmon is to describe its production methods (grey flesh is dyed ‘salmon pink’ to resemble its wild cousins). This is their recipe: once the reader has ‘digested’ the text, they no longer wish to eat farmed salmon. The ‘dish’ that they produced was a menu free from farmed salmon at the Tate gallery.

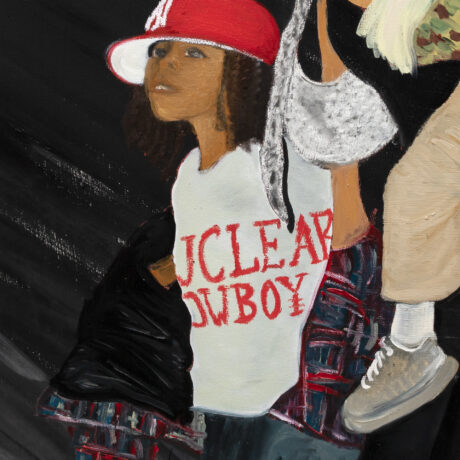

The recipe becomes a memorial in the hands of American artist Lyle Ashton Harris. He punctuates the recipe text for ‘Lyle’s Greens’ with photos relating to his family history, everyday life, and racial violence. Alongside the list of ingredients, Harris places a luminous portrait of his grandmother Joella Johnson, suggesting (though not explicitly stating) the history of the recipe.

“The images are part of the recipe, the making and eating of which becomes a practice of mourning and of survival in the wake of racist violence”

Harris’s recipe is also dedicated to George Floyd, who was murdered by the police in May 2020. Alongside photographs of growing and cooking the ingredients, Harris writes: “Trying to stay sane in New Garden in Germantown, NY. Dedicated to George Floyd, May 27 2020; First harvest, jalepeño pepper; Shiitake mushrooms; and sautéed greens.”

The images are part of the recipe, the making and eating of which becomes a practice of mourning and of survival in the wake of racist violence. The leftovers of ‘Lyle’s Greens’ become another recipe, ‘Good Morning Frittata’, depicted in a photograph.

Some artists present recipes without contextualising information. Subodh Gupta’s ‘Jungli Maas’, a curry made with mutton and potatoes and flavoured with homemade garam masala, exposes another important aspect of the recipe: to truly receive its message, you must perform its instructions.

What happens when we write down a recipe? What even is a recipe? We translate physical actions into language, so that they may be translated back through the body into a dish. The recipe gets to the heart of the tussle between language and embodied, material reality.

When I try to follow my own recipe text and cook a dish a second time, I realise that it can never be the same again. The more I cook and record these intuitive actions, the more I realise that the recipe does not reside in language alone. It must be lived to be known.

A recipe is a basis for new translations, for new dishes cooked by many hands. The recipe returns language to the body to be articulated differently again. And again, and again, and again.

The Kitchen Studio: Culinary Creations by Artists

Published by Phaidon, September 2021

VISIT WEBSITE