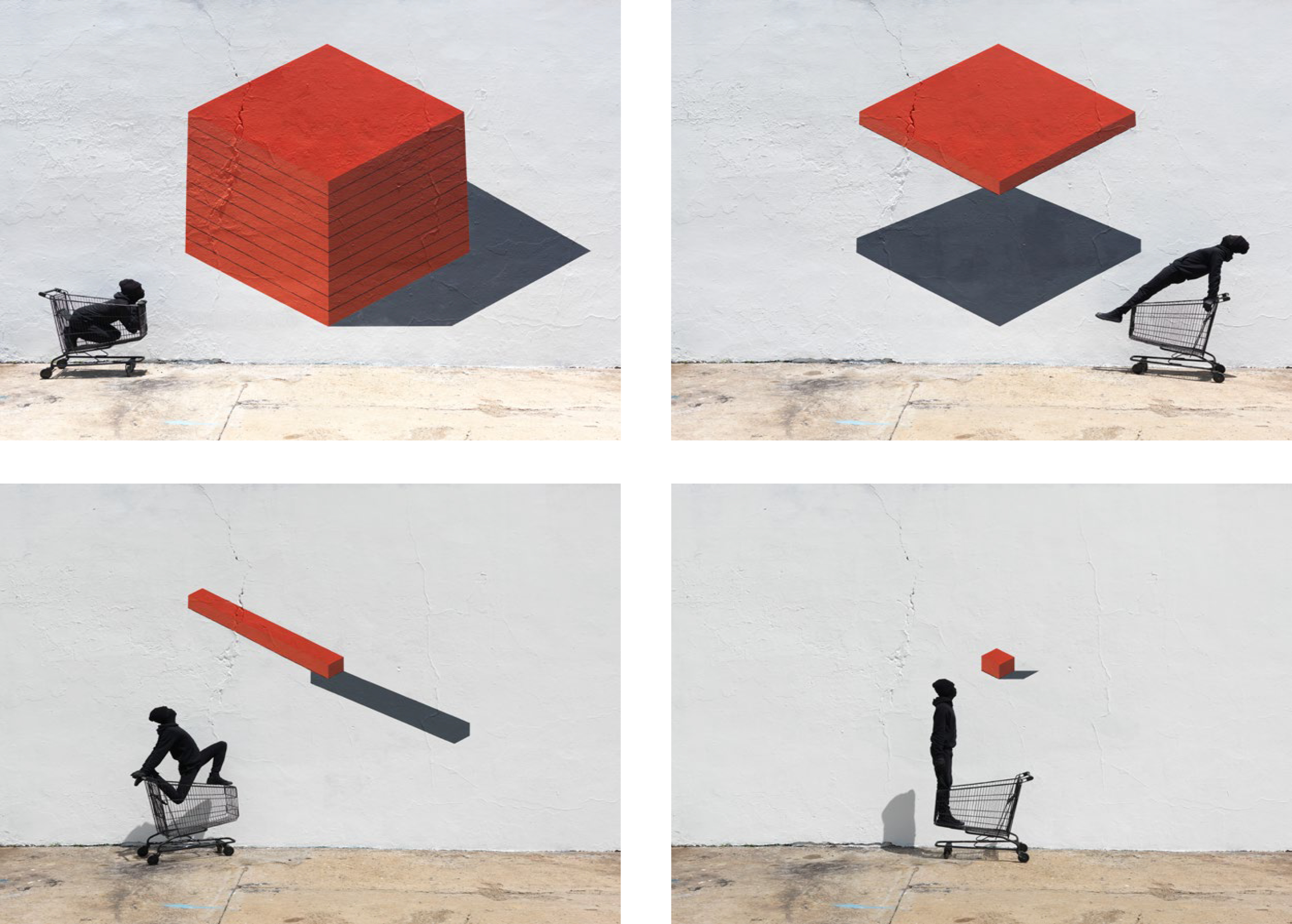

There’s a certain amount of evangelism in the way Robin Rhode speaks about his latest work. “What is key to this whole series is this crack in the wall,” he says, pointing out a long, jagged seam pervading the series of photographs he’s created of his otherwise perfected large-scale, colourful wall drawings of various shapes, painted on an unidentifiable street somewhere in Johannesburg. “When something is cracked it means it’s breaking; it’s broken. I like to think of my work as something that’s forcing itself through that crack. That wall, it’s going to collapse. Like the Walls of Jericho.”

It’s not the first time the South African-born, Berlin-based artist uses biblical references as we walk through his current exhibition at New York

’s Lehmann Maupin gallery in Chelsea, just before it opens. He tells me that over the past three years he’s been making trips to Palestine, which inspired one of the first works in the show, Under the Sun, a gridded series of photos charting an aggregation of identically sized squares, painted on a street wall and ranging in hue from canary to crimson; the number of shapes steadily increasing by each image frame. “I was struck by the sun there, how it’s this miraculous force with a strong spiritual symbolism across Christianity, Islam, and Judaism.”

Rather than any one religion, however, Rhode found salvation in geometry. “I’ve become really interested in mathematics even though I don’t come from that kind of background,” he tells me. His most recent projects are decidedly more organized in their aesthetic, compared to his earlier work. In the past two decades, his career has come to span drawing, performance, film, and photography, but he made a name for himself while still at art school in Johannesburg in the late 1990s by creating frenetic, scribbled wall drawings. Those works were as much about the actual marks as they were the performance of making them and the aesthetic was a product of and response to the energy of the newly post-apartheid city streets. The same streets on which he had grown up and witnessed the seismic shifts in social structures first-hand.

“I was struck by the sun there, how it’s this miraculous force with a strong spiritual symbolism across Christianity, Islam, and Judaism.”

The latest photographic works at Lehmann Maupin feature many of his hallmarks: a blank wall, a figure captured mid-movement in front of it, an occasional bicycle as prop. But the geometric shapes that have been inscribed in these scenes present an altogether different ethos, one that seems almost didactically outlined in Under the Sun, in painted squares cover pre-existing hurried black squiggles like those seen in Rhode’s previous works. “It’s like a sunset, or maybe a sunrise,” he says, which maybe alludes to the how these works are a pivotal moment in his career, ushering in the end of one phase and the start of another.

When I ask what prompted this desire to use tightly defined shapes rather than freeform lines in his compositions, he says he needed a way to order the universe. “I felt like I needed a new method, something that rejected chaos. I was looking for a spiritual calmness.” He doesn’t say much about the specifics that prompted this search, but his quest for tranquility led him to research the tenets of sacred geometry and Kabbalah texts, as well as to other artistic precedents in the work of greats like Le Corbusier, looking for expressions of universality through the use of mathematical precision.

“The cube is a massively symbolic geometric shape,” Rhode says, pointing me to a triptych of photos, Three Nudes, a succession of flesh-coloured cubes nesting in one another. “This one relates to the universality of being in a body; I was thinking about Leonardo da Vinci’s proportions of the body, the Vitruvian Man, this quest for an ideal.” The cubes, each one nesting inside the next, remind me more of a Russian doll as designed by the messiah of minimalism Donald Judd, who—in all fairness—had a similar drive toward a conceptual ideal.

Rhode is no stranger to minimalism, of course, especially since his earlier wall works were unequivocally compared to Sol Lewitt’s large-scale wall drawings from the 1960s and onwards. I ask if Lewitt was a big influence on him, or just an easy association critics like to make; Rhode says that the artist is one of his icons. “I actually call myself the Son of Sol,” he jokes. I assume this is a pun on the Old Testament figure of King Saul; I don’t mention that Saul ordered an assassination hit on his son, Jonathan, in the Book of Samuel, although it occurs to me later that maybe that patriarchal tension is part of Rhode’s relationship with Lewitt. “In school, I was fascinated by minimalism. I thought how amazing it was to distil the world into a single thing—one shape, one colour, one mark.”

He says he wanted minimalism to do more, however. “For me, it wasn’t just a conceptual exercise.” Rhode has largely assumed the role of director now, just as Lewitt did when he started outlining guidelines for a drawing, rather than sketching it himself. Where once it was just Rhode and his chosen wall in a graphic dance, over the years he has become more of a choreographer, sketching the initial designs beforehand from his studio in Berlin, before arriving in Johannesburg to realize them. In creating his latest sacred geometry-inspired works, he amassed a crew of fifteen to twenty local youngsters aged from eighteen to twenty-three—disciples, if you will.

“I took to instructional wall drawing because of social pressure from working in this place, on this street,” he says, when I inquire as to why he exponentially expanded from a team of just himself and two others to a veritable cohort. He notes that he didn’t mean to recruit so many hired hands, but instead a handful of them approached him for work, and his army grew from there. Indeed, he refers to his helpers as soldiers. “I’m the general, then I have a few corporals, then there’s the infantry.”

“I want to challenge the discourse around production and even the relevance of art in these circumstances.”

I joke that it sounds like he might be starting some sort of coup or crusade, but this sort of militance may well be helpful, if not necessary. “In this neighbourhood in Johannesburg, there is crime. There are gangs. There are drugs. There’s massive unemployment. I felt like, if I’m going to be here, in this place, I need to support and guide these young people. Give them some structure.”

Rhode is careful not to mention exactly which neighbourhood he’s been working in: “I’ll just say there’s a lot of conflict in the area”, but it’s precisely that sense of conflict that drives his work there. Each wall drawing exists for only forty-eight hours, the same specific section whitewashed and the shapes drawn the first day, then painted in and photographed the second. He even has some of his foot soldiers sleep in front of the wall overnight to prevent vandalism. But the amount of work that goes into the process and the pared down simplicity of the finished image are at complete odds with one another. “It’s through that tension that I’m trying to visualize the labour of this disadvantaged community. I want to challenge the discourse around production and even the relevance of art in these circumstances.”

I ask, hopefully not too sceptically, if art is relevant in these circumstances. Like any good proselytizer, Rhode vehemently but not ungently assures me—evidently the Doubting Thomas in this instance—that, yes, it is. The beauty of geometry is that it relies on proofs, but art requires faith. Somewhere in the middle of ordering all of the chaos, of looking for proof while relying on faith, there’s what he calls a “rehabilitative element” that geometric abstraction offers. I think that might another term for redemption.