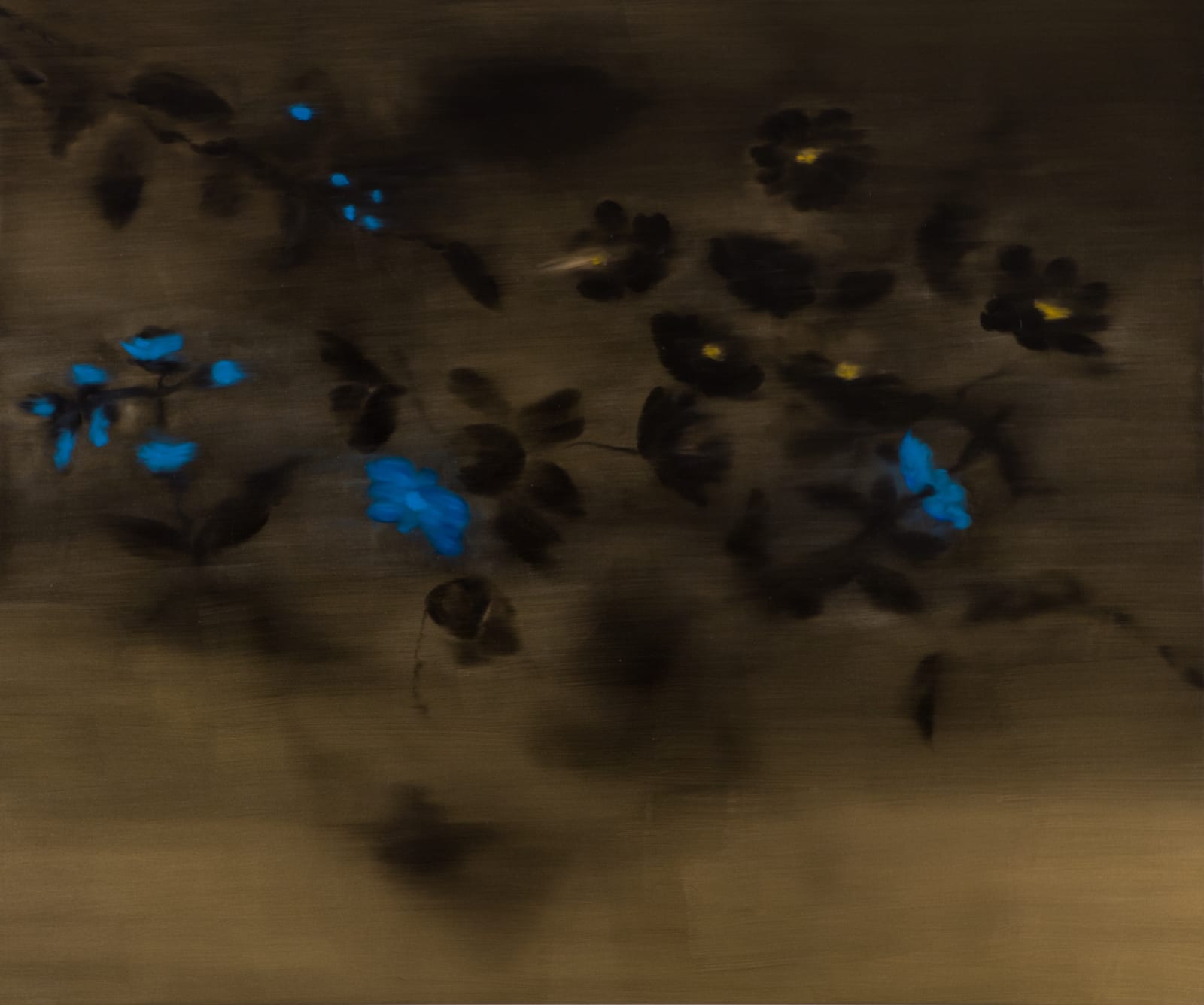

Divided by Zero, 2020. All images courtesy Capitain Petzel, Berlin

Ross Bleckner’s work often touches on human vulnerability, evoking both the psychological struggles of the mind and the viruses that attack the physical form. He started his practice in the 1980s, when New York was in the grip of the Aids epidemic. He responded to this time through painting, and by starting an organisation which focused on alternative therapies and education. As he tells me, “that’s when I realised there are limitations to being an artist. You can say as much as you want to say, but some things you have to do outside your studio.”

He is interested in how people respond to traumatic times, and in the mechanics of the brain. He has previously stated that the soft focus that hangs over many of his works reflects the way the mind works. Many paintings take their cue from scientific mateiral, including My Sister’s Brain (2012), which interpreted a brain scan of his sister, who is schizophrenic. His output is emotional, often reflecting upon troubling times for society as a whole.

“I’m naturally very optimistic in my pessimism!”

An exhibition of his works opened last month at Capitain Petzel

in Berlin. Quid Pro Quo brings together works “made in the solitude of my East Hampton studio, [which] reflect on the failure of one generation to pass a better world along to the next”. Since the pandemic hit in the United States, he has also created Covid works, which depict a conglomeration of masked faces and more obscure abstract forms, and x-ray-like views of chest bones, full of bright painted marks, whose vibrancy belies the horrific nature of this deadly disease. I spoke with Bleckner over Zoom about fragility, the destruction of humankind, and how the world has changed since he began making work.

You have dealt with human vulnerability and fragility a lot in your work. When you started painting in the 1980s, the US was going through the Aids epidemic. How has the pandemic influenced your work this year?

I was working on the paintings in this show before the pandemic happened, and I’ve been working on some new paintings since. One of the Covid paintings is called You Were Always on My Mind, after the Pet Shop Boys 1987 cover of the song, because this thing is always on our minds. How do we get it not to be on our minds?

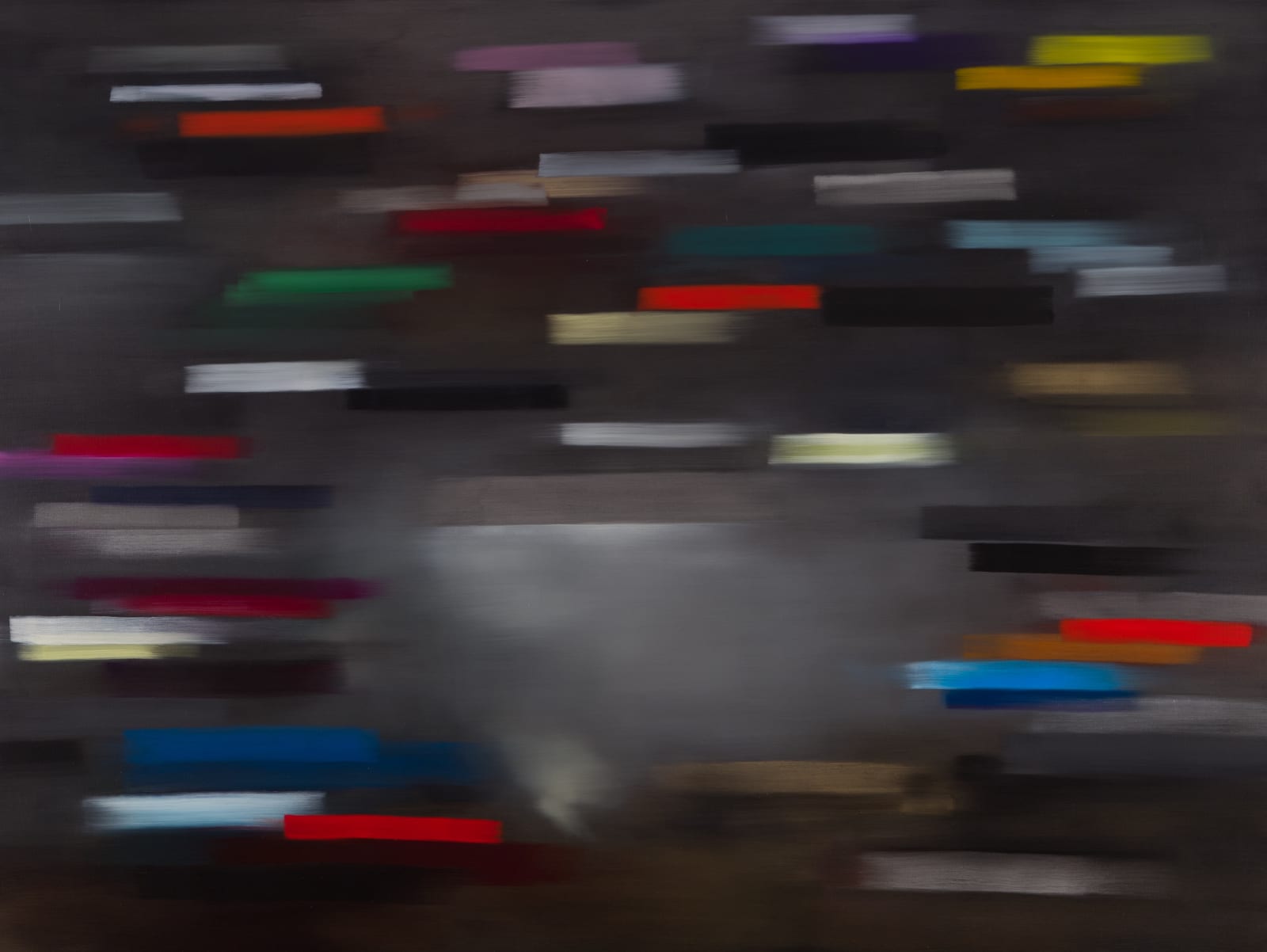

Another very abstract series of paintings has to do with the failure of our political discourse now. How do you get away from the proliferation of the rabbit holes of group think? The work was my attempt to find a more authentic voice in painting that represents an emotional coming to terms with the turbulence that we all feel today, spiritually and personally. Fundamentally, I think in emotional terms. My paintings span the range from dark melancholy to the joy of having pleasure through it all; somehow finding some grace and beauty in this mess.

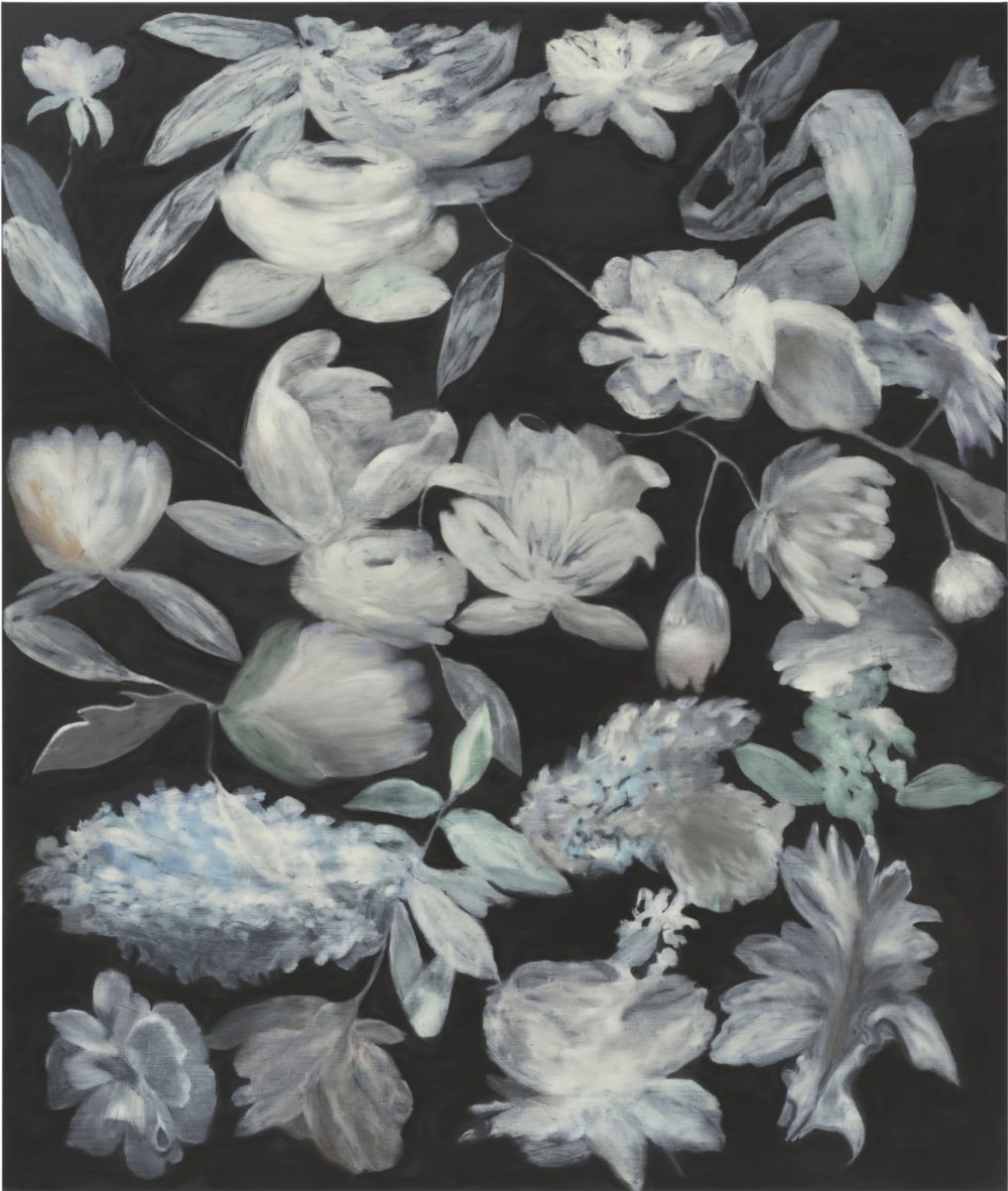

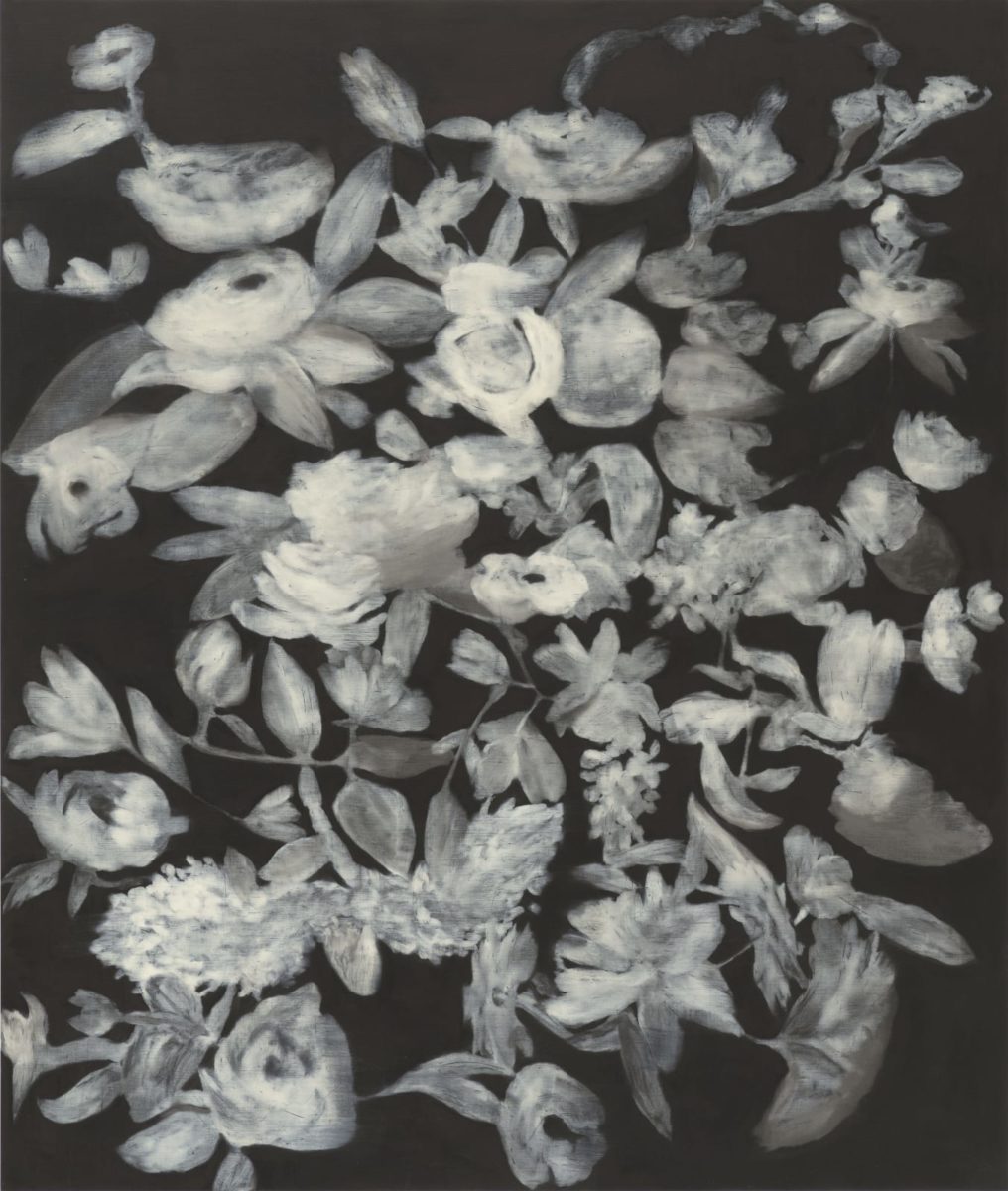

- Outside His Window (left); Outside Her Window (right), 2020

You’ve often spoken about yourself and your works as swaying between optimism and pessimism. How has this balance changed for you and your work over the years?

I’ve always been like that; I’m naturally very optimistic in my pessimism! My pessimism is more reality based and my optimism is a wilful delusion that we have to somehow create a positive narrative for ourselves or things get really depressing. Especially now. All I remember from my generation was good political intensions. There was the rise of activism, feminism and gay rights.

“The idea of fragility has interested and scared me my whole life: how close we all press to the glass”

I grew up in the 1990s and early 2000s, with Bush and Blair. On the whole my generation was pretty politically disengaged, but I definitely felt this belief in “progress”, that everything moves in the right direction over time. The bubble has definitely been broken now. How have you noticed optimism in society developing or changing?

All the way through, from Lyndon B Johnson to, God forbid his name—the monster!—it’s been up and down, but people have these delusions that the arc of the world is toward justice. It’s kind of naïve. How do you find justice in a corrupt world? But I do see how so many young people are having an effect on the discourse now. If Trump did anything, he took the bandaid off so many delusions; this wound that was always covered by political platitudes.

The Aids epidemic became a moment of rupture for me. How can you go on with business as usual, and all around you this is happening? My life is parenthetically bracketed by dealing with the Aids crisis, and now we have this pandemic. Who knows how it’s going to go. We’re going to be living with this for a long time, one way or another.

You mentioned painting being an emotional experience for you. Do you find it a form of catharsis in difficult times?

In my mind, I’m always looking to make new paintings. I hope there is some kind of mutation in the way that I put it together that something new will be born. It’s very organic. The mistakes become the next body of work. I am always looking for the vulnerability, or the break in the chain.

During the Aids epidemic, I had to decide what I was going to do. I had friends who died. I am not really a protester, so I helped start an organisation that I was the president of the board of for 18 years. It became really important and I actively worked with it. It is called ACREA, and at that time we tried to fund pharmaceuticals, startups or individual doctors, different alternative therapies that the FDA wasn’t looking into. It led to some treatments and protocols. There was a lot of education and outreach to minority communities about health options and prevention.

“I am always looking for the vulnerability, or the break in the chain”

That’s when I realised that there are limitations to being an artist. You can say as much as you want to say, but some things you have to do outside of your studio. My paintings deliver a certain representation of my feelings, what I’m thinking about. But to deliver what I’m thinking about into action takes not being a painter, it takes being in the world as well. They inform each other completely though. I’ve always been a news junkie, so there is no way that what’s going on in the world is not going to be reflected in the tenor of the work.

I have read that the soft focus on your works is a reflection of how the mind works, as it shifts from thought to thought, sometimes forgetting a thread and moving on. Could you tell me a bit about the correlation between painting and the brain for you?

I actually did a whole series of paintings about brains a few years ago; I took brain scans and painted sections of them. The scans went from monastic peacefulness, to a scan of somebody on crystal meth, which looked totally chaotic. And I painted a brain scan of someone with schizophrenia, which was my sister.

The idea of fragility has interested and scared me my whole life: how close we all press to the glass. It just takes one little flip and you are on the other side. In our bodies, everything is perfect, we carry so many organisms that thrive. Yet our species is ridiculous, in a short time it is destroying itself. In the 1990s, when I did these paintings of cells and diseases, cancer, HIV, I was looking at them in petri dishes and stuff like that, and I realised that we are all one thin membrane away from disaster.