In London, in the summer, Sam Falls also featured in two group shows at Sadie Coles HQ and at the Zabludowicz Collection, with whom he has done an artist’s residency on the Finnish island of Sarvisalo. At Sadie Coles he showed work featuring the imprint of huge palm leaves on weathered canvases splattered with rain saturated with pigment, while at the Zabludowicz Collection there were boldly painted aluminium sculptures and a recent series of five video works using appropriated scenes from Tarkovsky films played against a segment of a Velvet Underground song.

Not having an allegiance to a particular medium is, Falls says, the thing that makes his interests ‘so expansive’. But as varied as his practice is, a clear conceptual thread connects these very disparate-seeming works. Falls is preoccupied by ideas of time, mutability and duration. His aim, as he’s said in an earlier artist’s statement, is to create works ‘formed over time, rather than captured in an instant’.

He does this with works that appear in large part to employ chance, but, surprisingly, the outcomes rarely surprise Falls. ‘A lot of people think it’s so involved with chance operations,’ he says, ‘but for me, it’s so obvious what will happen, because, I mean, growing up, especially as I did on a farm in Vermont and hiking a lot and really living out of doors, spending so much of the time in the woods, it’s like you get a better sense of what’s going on… I don’t know, it’s like being very familiar with the sun and the rain and knowing how they’ll interact with materials. It’s a really good question to ask, but the work isn’t really about chance.’

As with much of his work, the palm leaf series is largely created by the elements. Falls coated the leaves with different-coloured powdered pigments and laid them on a canvas, which he left outside in his backyard in la. The weather did the rest, creating large splashes of colour around each leaf as the rain lashed down. A similar series he did with fern leaves in Vermont from his mother’s garden shows a fine misting of colour instead, demonstrating the differences in rainfall. Clearly, location is as important to the outcome of each work as the process of time.

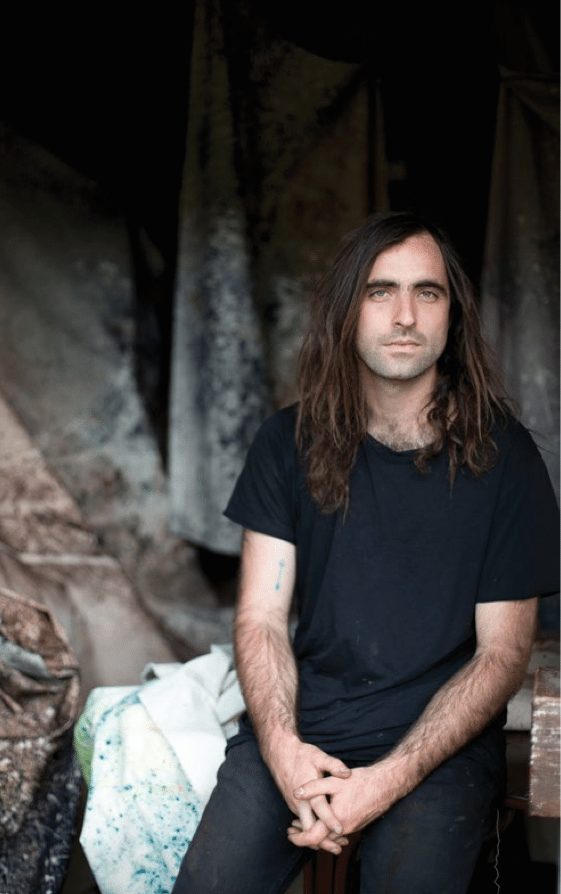

Having spent his first five years in San Diego, California, the five-year-old Falls moved with his family to New England. He studied as an art history/critical theory major in Portland, Oregon (having originally intended to study physics, then English, then philosophy), then moved to New York as a graduate student in photography. A year after graduating, during which he also worked part-time as a photographer in the commercial industry to earn his keep—it provided a steep learning curve, but he says it made him realize fairly quickly that commercial work, however lucrative, was not something he wished to pursue as a life’s ambition—he left New York for LA.

He now moves frequently between the two cities, having also bought a house with his wife in upstate New York. However, he seems currently to be spending most of his time on the sunny West Coast. Incidentally, although he now mostly shuns commercial work, and is reluctant to dwell on it at length in this interview, he has done one or two high-profile commissions since, including a Dazed & Confused cover with Björk, for which he overpainted her photographic image with bold and colourful gestures. He clearly, however, makes a distinction between his artistic practice and the commercial work he’s done to earn money.

The move West has definitely changed the way he works, he says. ‘The scale has changed. Once I moved to LA not only was it easier to have a larger studio than in New York, but I started working outdoors all the time. In New York you’re almost constantly shuttled between what feel like rooms—you’re in a subway in a “room”, you’re in a taxi in a “room”, and even when you’re on the street it feels so boxed in that you feel you’re just in another room.’

But although his long hair and his slightly flat delivery make him look and sound like a pretty laid-back West Coast kind of guy, Falls says he finds the change of pace ‘a little frustrating’: ‘I really enjoy the quick-paced nature of New York, and I’m more in tune with that kind of daily activity. But part of the goal of moving to LA was to work on the sun pieces outdoors.’ He’s referring to his large-scale aluminium sculptures, which have an interesting spatial relationship to the viewer.

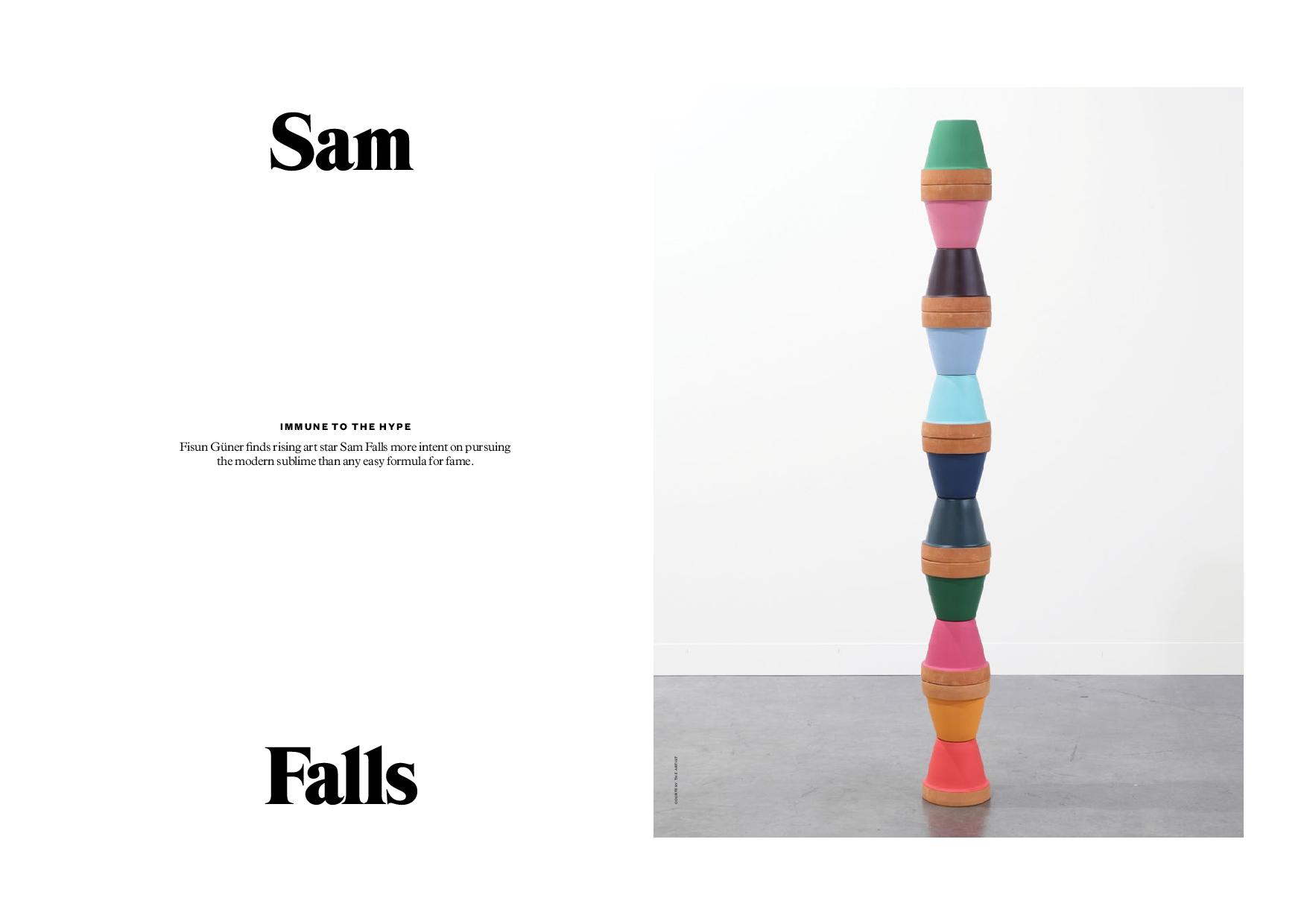

Falls paints these sculptures in incredibly bright, seductive colours, sometimes in a single vibrant hue, but often with each panel pulsating with a different zingy one. He coats their outside panels in uv-coated paint, while the inside panels are left uncoated. This means that the colours of the uncoated panels fade with the sunlight, and will eventually lose most of their colour. ‘In the sun the angle of the shadows hits the inside and so it makes a kind of gradient,’ he explains, ‘and it will fade faster in the sun, depending on where the shadow is—so each sculpture is a different shape.’ So at least in this case there’s an element of uncontrolled chance that Falls can’t perhaps anticipate.

It almost goes without saying that Falls feels very connected to the American art of the ’60s and early ’70s. In his sculptural works, Donald Judd is the obvious departure point. Falls talks of his first visit to Marfa, in the desert region of West Texas, where the Judd Foundation maintains Judd’s work as it was originally conceived in the late artist’s vast and sprawling living and working spaces. It was an experience, he says, that ‘kind of blew me away’. But though Judd’s deep influence and that of other minimalists like Robert Irwin have undoubtedly informed Falls’s work, he ultimately does have an issue with ’60s minimalism, which he broaches in his own sculpture.

‘A lot of minimalism is cold and unchanging and it kind of blocks out the viewer.’ The movement, he says, was ‘more about the artist and the object, a conceptual idea rather than an impassioned relationship with the viewer’. Falls wants his own work to ‘deal with the issue of taste more’, since ‘taste varies, rather than being some kind of pure beauty in form, which I think a lot of minimalists thought they could achieve but is, in fact, impossible’. He agrees that he wants his work to be slightly less ‘authoritarian’.

Falls also acknowledges that his work connects with a lot of the land art that emerged from the early ’70s, citing the importance for him of Michael Heizer and Robert Smithson, but adding that their work was also ‘very assertive and not compassionate for the viewer’, which Falls feels can be more than a little intimidating. ‘It was either a cold conceptualism or masculine intrusion, and I feel like I’m on the opposite end of that spectrum, even though I’m a man.’

Though Falls’s work isn’t, at least not yet, on such a grand scale, and neither is it impossible or near-impossible to reach in terms of its setting or remote geography, or the fact that, in the case of Smithson’s Spiral Jetty, none of it has sunk into the sea, the notion of the modern sublime engages Falls. Not only do the natural elements complete the work and therefore connect with the recent history and mythology of land art, but his work engages with the whole question of the power of artifice versus nature that historically the Romantics were engaged with. That and the theme of representation and abstraction, and the ‘duality of all that’, exercises Falls. The leaf canvases clearly play with all these ideas.

I ask Falls what the dangers are, if any, of achieving success at such a relatively young age, so soon after graduating. Isn’t there a pressure to keep on reproducing the same kinds of work that people first noticed you for? (Though so far Falls seems to have avoided any such pitfalls.) ‘I just don’t work with those kinds of people,’ he says simply, ‘which I think is a decision not every young person makes. I mean, it’s tricky, but the easiest thing for me was always just to do what I wanted rather than what was expected.’

He adds that choosing to be an artist was, for him, a decision of integrity, and that the success, and the inevitability of being grouped with other artists as part of an emerging ‘hot LA scene’, as Falls has been, is a kind of distraction. Or, as Falls more boldly puts it, ‘a kind of bullshit’.