My Sweet Doppelgänger, a group show currently at Richard Heller gallery in Los Angeles, invites artists to create their own double. Inverting the frequent idea that the doppelgänger is a more sinister counterpart, artists in this exhibition explore positive doubles for themselves, with many creating abstract or semi-abstract works which reflect their personal characteristics and interests rather than their physical bodies.

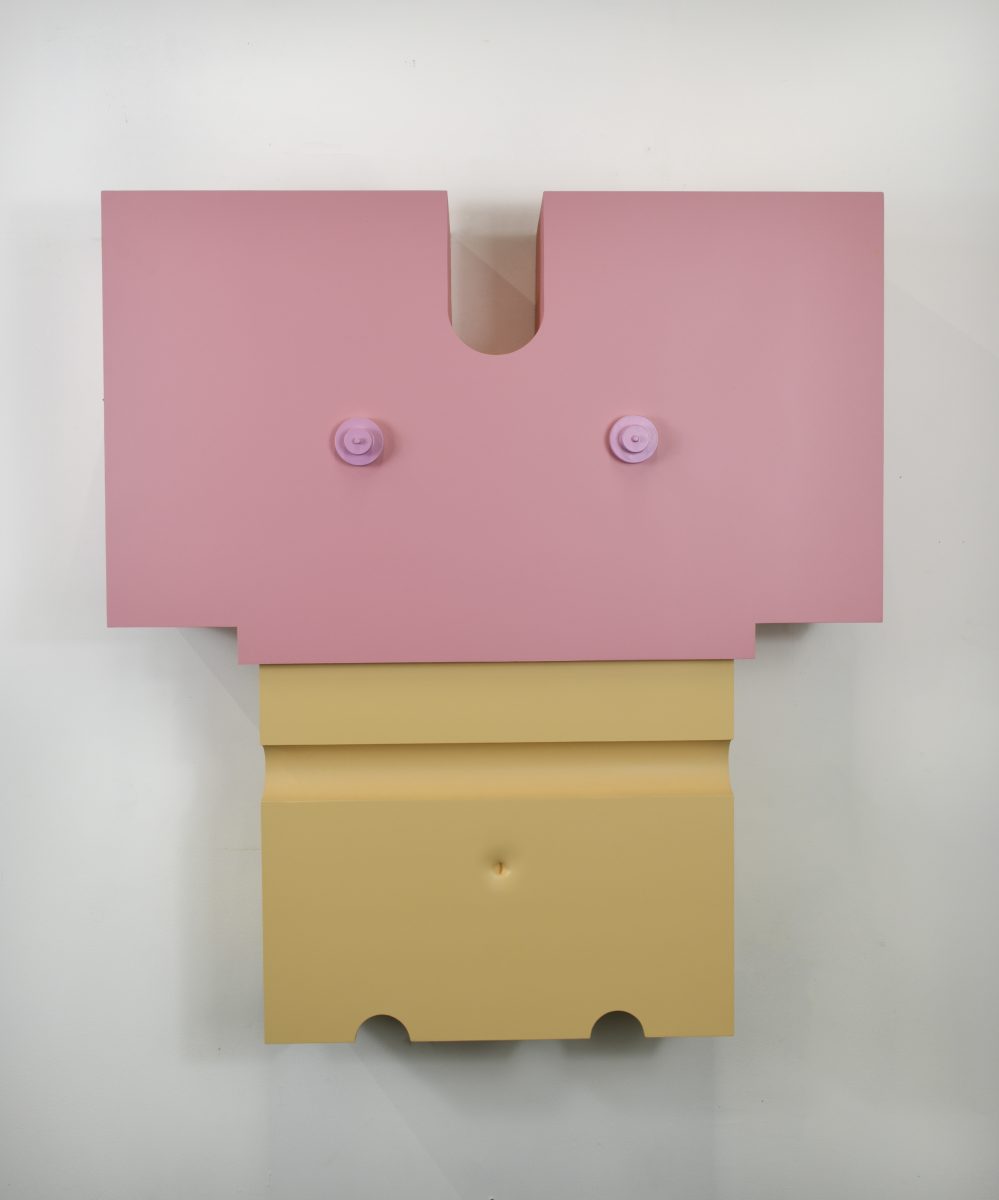

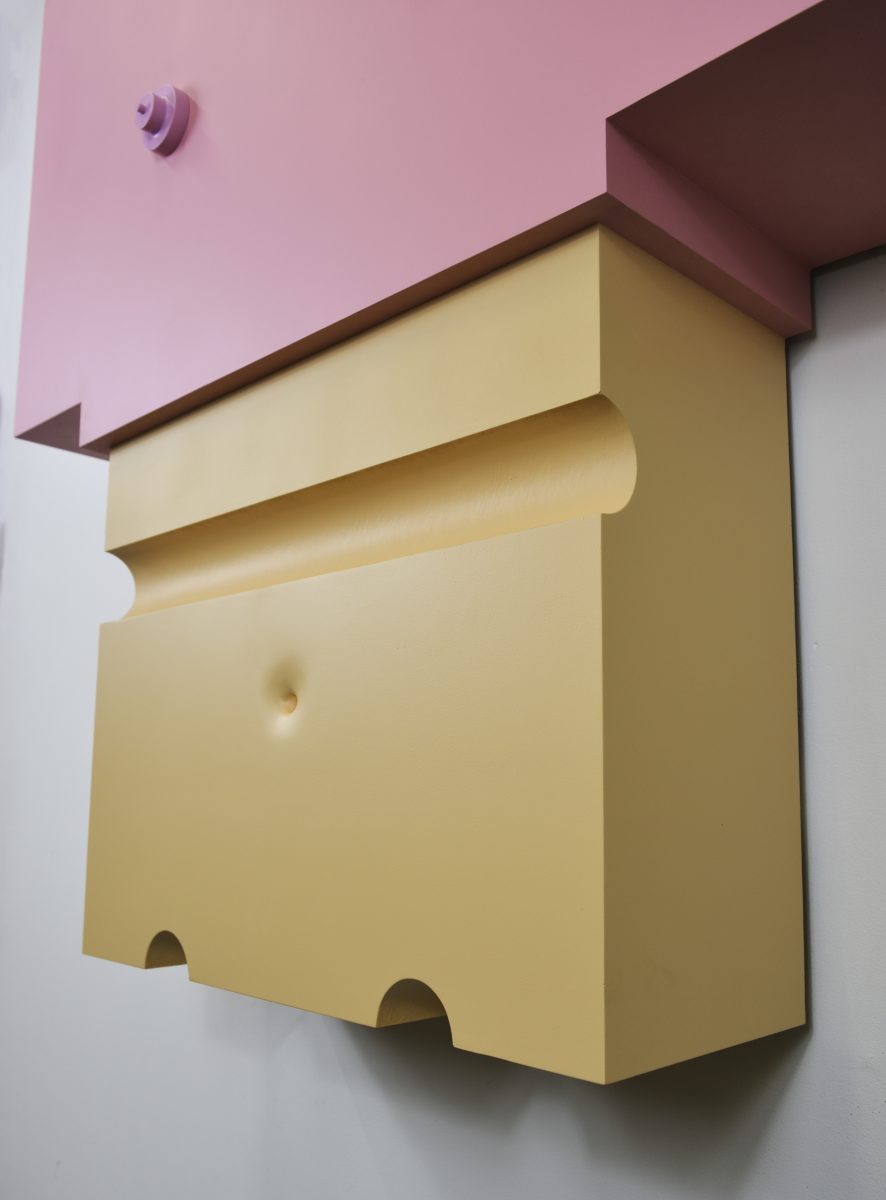

Liam Fallon created a combination of both. The Manchester-based artist’s work, Inhale, brings together the formal simplicity of abstract sculpture with a few choice nods to the human body: a super-realistic bellybutton, cast from his own, and a pair of round nipples allude to a fleshy torso, which is depicted in bright pink and orange. While this has a very obvious connection with his own body, the piece also evokes broader messages of desire, love and loss.

My Sweet Doppelgänger invites artists to imagine a “benevolent and friendlier” double of themselves. Can you tell me a bit about Inhale, and which parts of yourself you wanted to show (besides the obvious!)?

I read a piece of writing last year on the subject of architectonics (the scientific study of architecture) and its relation to the human form. There was a quote at the beginning which referenced classical architecture being directly inspired by the human form: it became this eureka moment for me. When you look at classical architecture you see really ornate cornicing, archways and materials, which are really seductive.

The most obvious reference to myself in Inhale is the belly button, which is a direct replica of my own and was made through a variety of casting processes. But ultimately, and possibly semiconsciously, another part which feeds into the work is my interest in New York’s Chelsea Piers. During the AIDs epidemic, Chelsea Piers was a safe haven for the LGBTQ+ community and it became a subject for a lot of photographers such as Alvin Baltrop. In the photos you can see a lot of people enjoying the pluralistic pleasures, as well as exhibitionism and voyeurism. These have naturally crept into the sculptures in quite a playful way.

“My interest lies in mundane objects and the hidden stories and sentimentality they often bare”

In this sculpture, typically fleshy nipples and torso are depicted using a rigid material. You have also previously depicted bricks being squeezed, flesh-like, by rope or being ‘unzipped’ down the middle. What is it about subverting the properties of different materials that interests you?

My interest lies in mundane objects and the hidden stories and sentimentality they often bare. The objects we come into contact with on a daily basis become totally overlooked. The task for me is to revalue and exalt them, so they are pushed to the forefront and take on new meaning. Materials become the main tool in my investigation of how to revalue objects: brick walls that are hollow or seemingly soft and malleable, laces made of rubber.

It’s about combining objects that are typically alien to one another to create a sentimental conversation between the two, often striking up conversations about desire, love and loss. There is a definite intention to anthropomorphise the works because it queers the object and changes its function.

You mentioned that you cast your own belly button for Inhale. Do you often work directly with source objects before adapting them into your sculptures?

It will usually be a very specific detail that I lift from sources, often the most identifiable or strongest section, such as a colour palette or a specific detail or form. This provides leeway to be a little more abstract with the wider sculpture, because once that detail is inserted into the work, it automatically becomes quite controlled and intentional. I never saw myself making something figurative, because it’s been done for such a long time, but I find this architectural twist in the approach to making really exciting.

“It’s about combining objects that are alien to one another to create a sentimental conversation between the two”

What was the first piece of art to have a profound impact on you?

It was Thomas Hirschhorn’s Candelabra with Heads (2006) at Tate Modern. I saw it on a school trip to London when I was 18. I’m originally from Stoke-on-Trent, so naturally the closest thing to sculpture I had seen was ceramics, which is linked to the heritage of the city. When I walked in and saw that sculpture, I couldn’t get my head around it. At that point I became interested in sculpture, particularly biomorphic forms.

My interests changed again when I saw Matthew Barney’s Facility of Decline (2016) show at Gladstone Gallery in New York. He used so many materials that I wanted to use, but I hadn’t worked out the recipe for within my own work yet. I went back to see that show three or four times before I flew home. On the last visit I sat down and ended up drawing the plans for my degree show work. Yet again, one of those eureka moments!

Use Your Muscle, Carve It Out, Work It, Hustle, 2017 © Colin Davison

What are you reading at the moment?

I usually have a few things that I’m working through slowly but surely. Currently I’m reading an essay about Robert Gober and René Magritte; What’s Love (or Care, Intimacy, Warmth, Affection) Got to Do with It? by Sternberg Press; and Ten Queer Thesis on Abstraction by David Getsy. They’re all slightly different but there is a constellation of links between them.

Emily Steer is Elephant’s editor

Images courtesy the artist