Somaya Critchlow’s solo exhibition at Maximillian William presents drawings whose medium is as intimate and striking as their subject matter; her delicately rendered nude figures on paper engage the historical and the symbolic to defy dominant approaches to Black sensuality, selfhood, and representation.

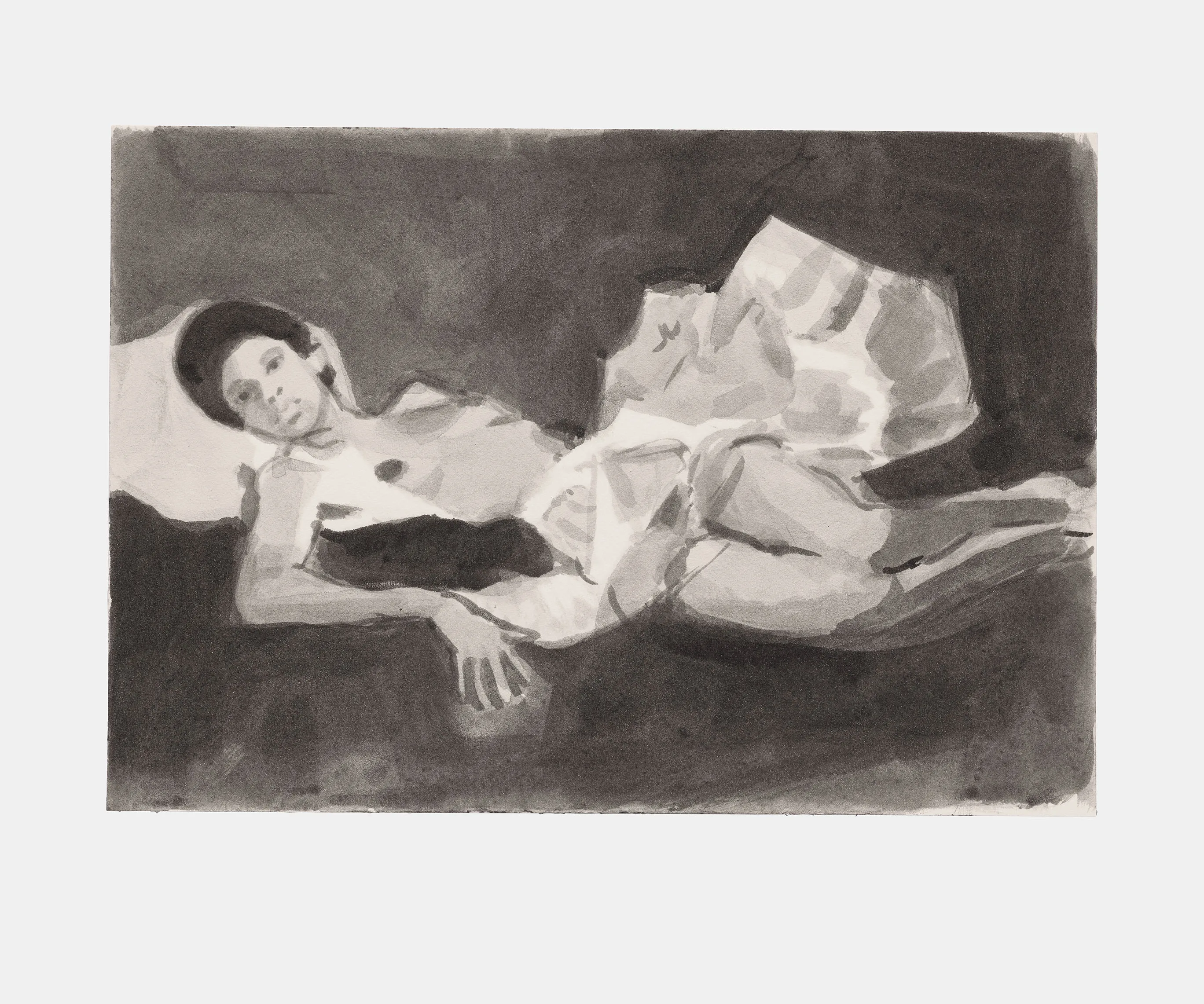

‘Men look at women,’ John Berger wrote in Ways of Seeing (1972). ‘Women watch themselves being looked at.’ Through bold and unflinching representations of the female nude, British artist Somaya Critchlow seeks to shatter the power dynamics that have long shaped the portrayal and perception of women in both art and life. Each of Critchlow’s paintings depict a solitary naked woman against the backdrop of a domestic scene, often holding an object or performing an action that seems at once mundane and symbolic. Critchlow’s nudes are not passive subjects, but figures which interrogate the very act of looking; they are self-aware and assertive, positioned within narratives that confront, challenge, and complicate reductive notions of Black femininity, selfhood, and representation.

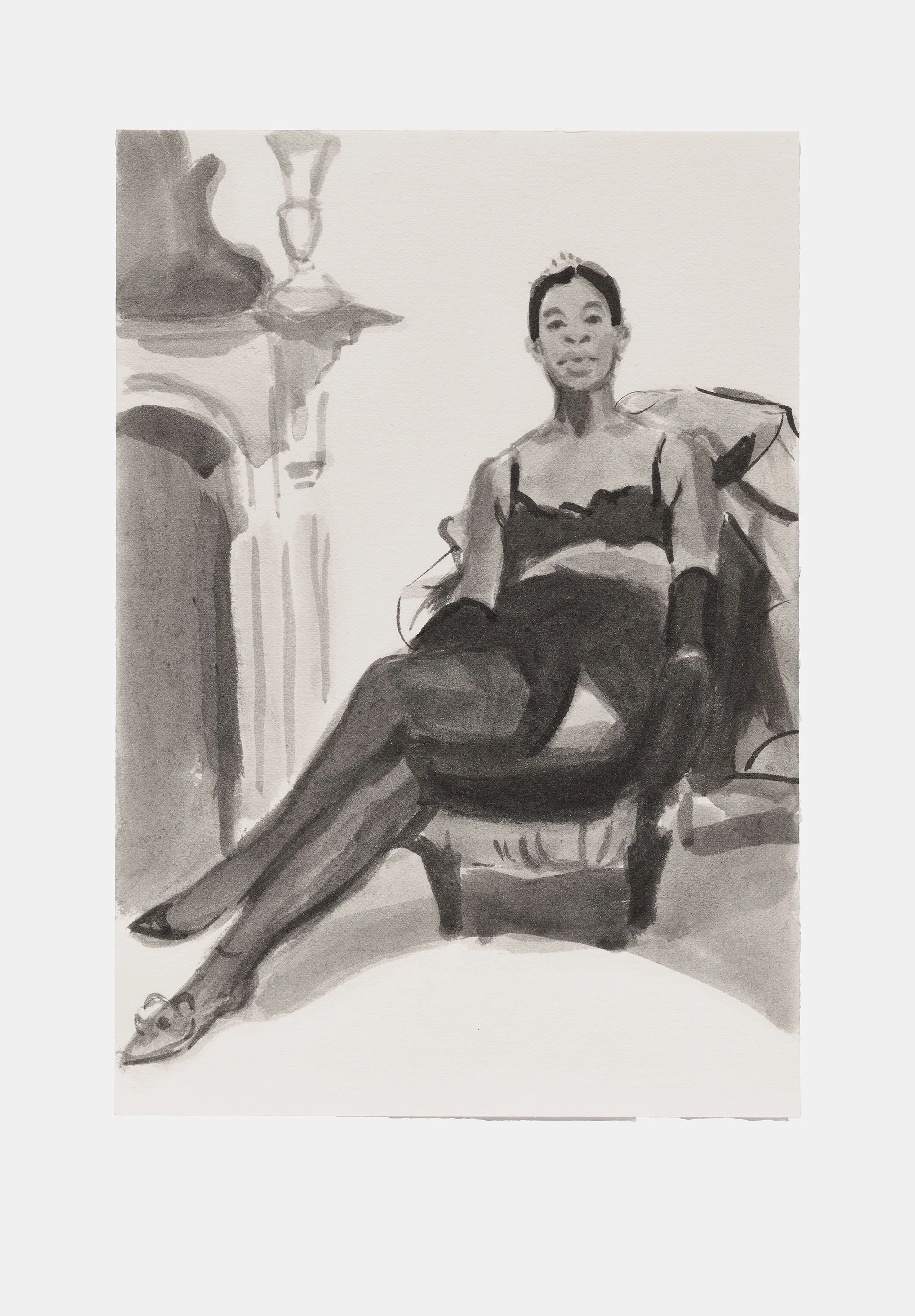

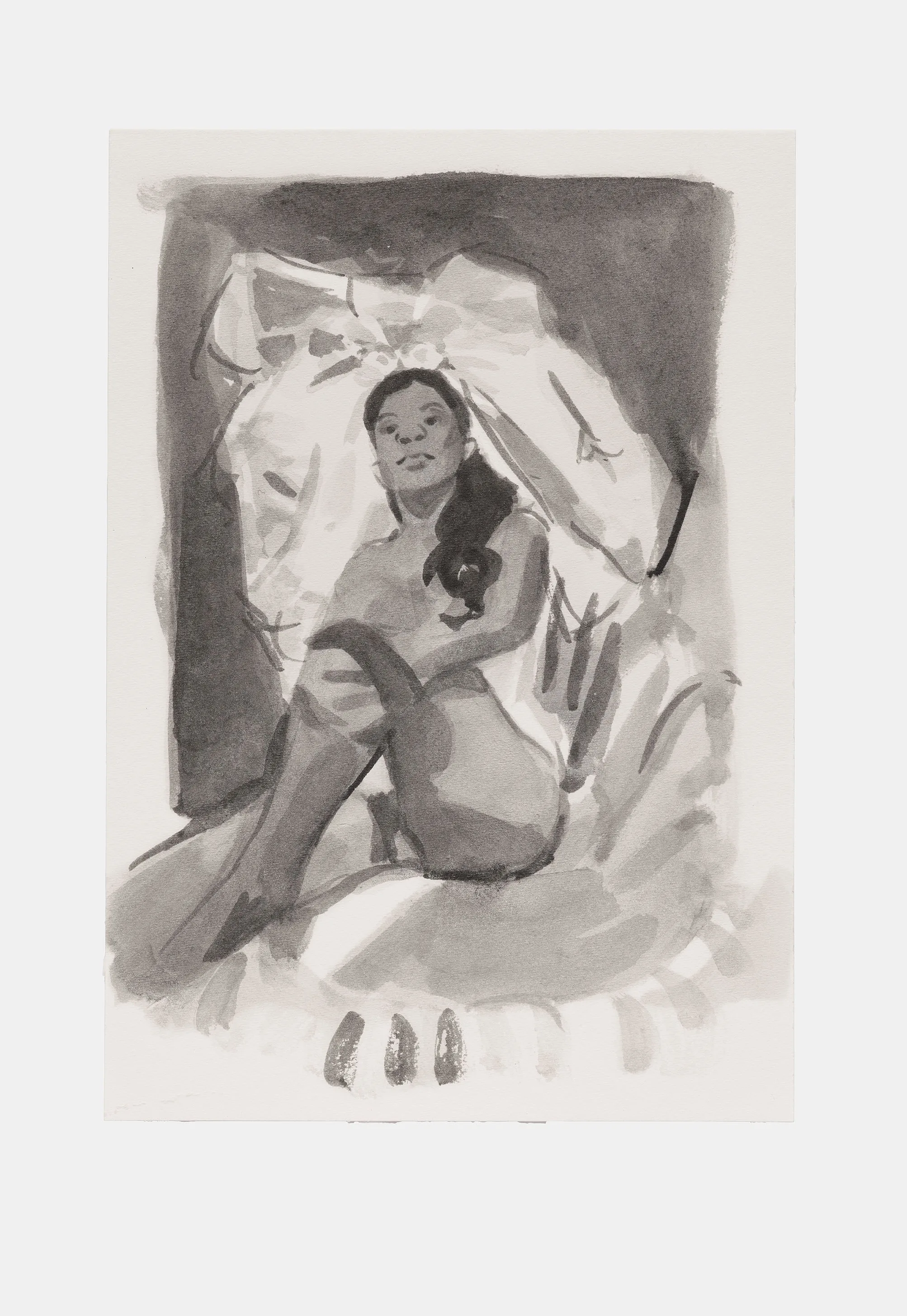

Comprising over forty recent works on paper, Triple Threat, Critchlow’s solo show curated by Hilton Als at Maximillian William, is the artist’s first exhibition to focus solely on drawing. Delicately rendered in graphite pencil, brush with ink, or glass dip pen, the drawings display the immediacy and spontaneity of a sketchbook. With more careful attention, however, each reveals a thoughtfully crafted narrative, where every line, gesture, and symbol is imbued with meaning and significance.

Critchlow’s fascination with the female nude places her within a long-standing artistic tradition, yet her approach is distinct and unmistakably contemporary, marked by a shift in perspective and power. She often uses her own body as a reference for her subjects, reclaiming agency in a genre historically shaped by the male gaze by positioning herself as an autonomous figure who directs how her body is portrayed.

While sensual, her nudes refuse to be eroticised in the traditional sense. As Berger remarks in Ways of Seeing, the viewer is used to being presented with a woman, often languid and naked as a symbol of her submission, gazing passively back at an anonymous male voyeur who she knows is observing her and to whom she strives to appeal. Critchlow’s subjects subvert this tendency, their exaggerated proportions disrupting the traditional ideals of femininity, beauty, and vulnerability. They often confront the viewer directly, challenging the gaze that seeks to define and control them. With their unusually unapologetic form of intimacy, Critchlow’s figures do not seek the viewer’s pity, sexual desire, or admiration, but demand acknowledgment of the complexities of being seen.

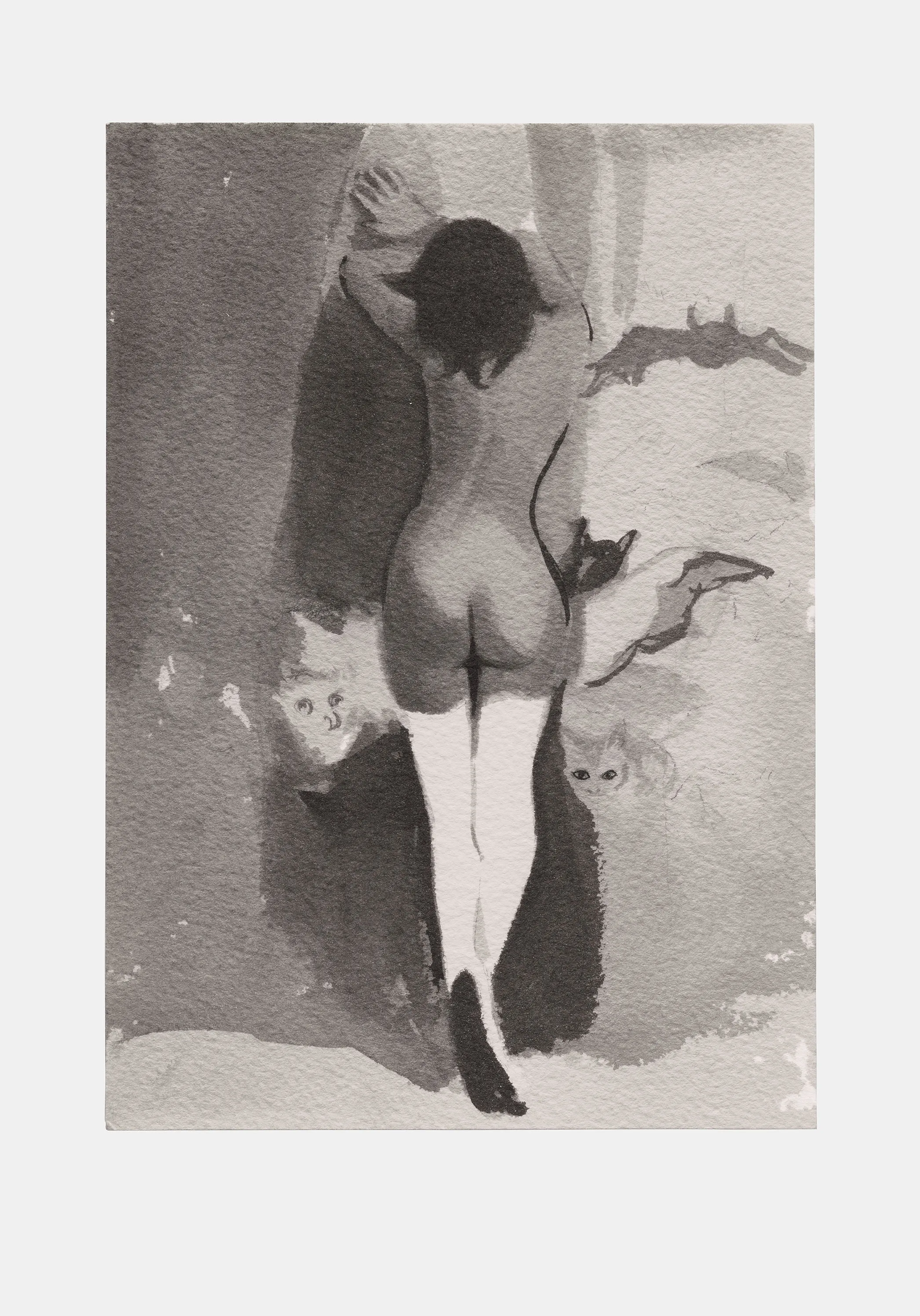

Recurring motifs of bridal veils, stockings, and animal companions suggest an exploration of societal roles traditionally associated with femininity, though these symbols are not presented in their traditional sense; separated from their familiar context and associations, they are subverted and undermined. In Study for The Bride (2024), the female figure holds her veil high with a precarious, almost contorted pose. The veil—a laden symbol of purity, tradition, and societal expectation—becomes a metaphor for the tension between societal expectations and individual autonomy. The figure’s vulnerability is palpable, yet it is tempered by a quiet, resilient strength—an underlying defiance against being fully confined by the veil’s symbolic weight. In Study of a Bride (2024), the act of removing a stocking, a gesture often coded as erotic, becomes a statement of agency and defiance. The figures may be exposed, but they are never truly vulnerable in a way that diminishes their strength: within their private sphere, performing their most intimate acts, they remain in control of their exposure and, in doing so, assert their subjectivity and autonomy.

Critchlow’s drawings bring forth the question of whether the nude body can ever exist as a space devoid of meaning and interpretation. This interrogation is most evident in the drawing Wicked Woman (2024), in which Critchlow reimagines Francisco Goya’s critique of hypocrisy and moral decay. Wicked Woman highlights how the female body—especially Black and Brown bodies—remains policed and commodified under the guise of moral judgment. Critchlow’s critique is not a direct imitation of Goya, but a bold reinvention rooted in contemporary culture. She blends historical references with the visual language of vintage soft porn, reality TV shows like Love & Hip Hop, and the provocative private photography of Carlo Mollino. This fusion of influences creates a compelling and eclectic collision of high and low culture, intensifying her exploration of modern femininity and sensuality. In Bonnet (2024), Critchlow extends this dialogue by drawing inspiration from William Hogarth’s The Painter and His Pug (1745), a satirical part-self-portrait, part-caricature that humorously reflects on Hogarth’s own character and role in society.

By positioning herself within a lineage that includes Goya and Hogarth, Critchlow not only critiques society’s gaze on the female nude, but also reflects on her own role in the artistic process. She navigates the inherent tensions in depicting the female body, acknowledging it both as a site of empowerment and a subject of scrutiny. Critchlow’s engagement with the art historical canon goes beyond mere reference; her daily reproductions of Goya’s The Caprices (1797–1798) and The Disasters of War (1810–1820) serve both as homage and an almost performative critique. These works ground her exploration of cruelty, power, and moral ambiguity in a historical context, yet they are far from static. By reactivating these pieces through a contemporary lens, Critchlow forces us to confront the unsettling reality that society’s relationship with the body, power, and representation has changed little over time.

This tension between past and present resonates with bell hooks’ concept of the “oppositional gaze,” as discussed in The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators (1992). hooks critiques the historical exclusion of Black women from visual representation, highlighting their long-standing subjugation to racial and gendered objectification. The oppositional gaze emerges as an act of resistance, where Black women refuse to passively accept marginalising portrayals and instead actively challenge and deconstruct these images. By reclaiming their sensuality, Black women not only reject stereotypical and hypersexualised representations but also carve out spaces for themselves to be depicted with autonomy. In this way, hooks argues, the acts of critically engaging with and creating alternative self-representations become subtle yet profound forms of empowerment, enabling Black women to assert their own identity and defy the oppressive visual narratives imposed by dominant cultures.

Through this lens, Critchlow’s work confronts the ways in which representation shapes our understanding of power, identity, and resistance. Triple Threat thus becomes a dialogue between artist and audience, past and present, body and self. Through her engagement with both the art historical canon and contemporary culture, Critchlow reclaims the nude as a site of meaning, agency, and opposition. In doing so, she offers a meditation on what it means to exist—and to be seen—in the world today.

Words by Sofia Hallstrom