Reality is difficult, and for some, vastly more so than others. As a consequence, alternative modes of existence– and survival– are constantly being developed, less as sites of escapism and more as containers for imagination and speculation, through which better worlds are envisioned and boundaries broken down. In fiction and other art forms, this is– in its broadest terms– known as SFF (science fiction & fantasy), or speculative fiction, that which departs in any manner from realism. In the differing but similarly resonant practices of Sibylle Ruppert and Shu Lea Cheang, both on view in two concurrent solo exhibitions at Project Native Informant, SFF is combined with eroticism to become a playing ground for subversion; the collapse of patriarchal barriers and heteronormative binaries.

I’d never heard of Ruppert before visiting her exhibition ‘Frenzy of the Visible’, the artist’s first solo show in the UK. I’d been hoping for a brief respite from a dreary day off in Bethnal Green, some glamorous, monster-sex escapism. From pictures I’d seen on social media, the colossal drawings and collaged works on display looked markedly contemporary, perhaps meditations on transhumanism as envisioned by artificial intelligence or observations of the slippery digital boundaries of sexuality and violence. Consequently, it was a shock to discover that the show was posthumous; Ruppert died in 2011, long before the realm of ChatGPT, Midjourney and Meta. Most of the works on display date from the 1970s, though they are disquietingly ahead of their time, strangely prescient of current cultural concerns and much more complex than my pre-visit judgement had allowed them.

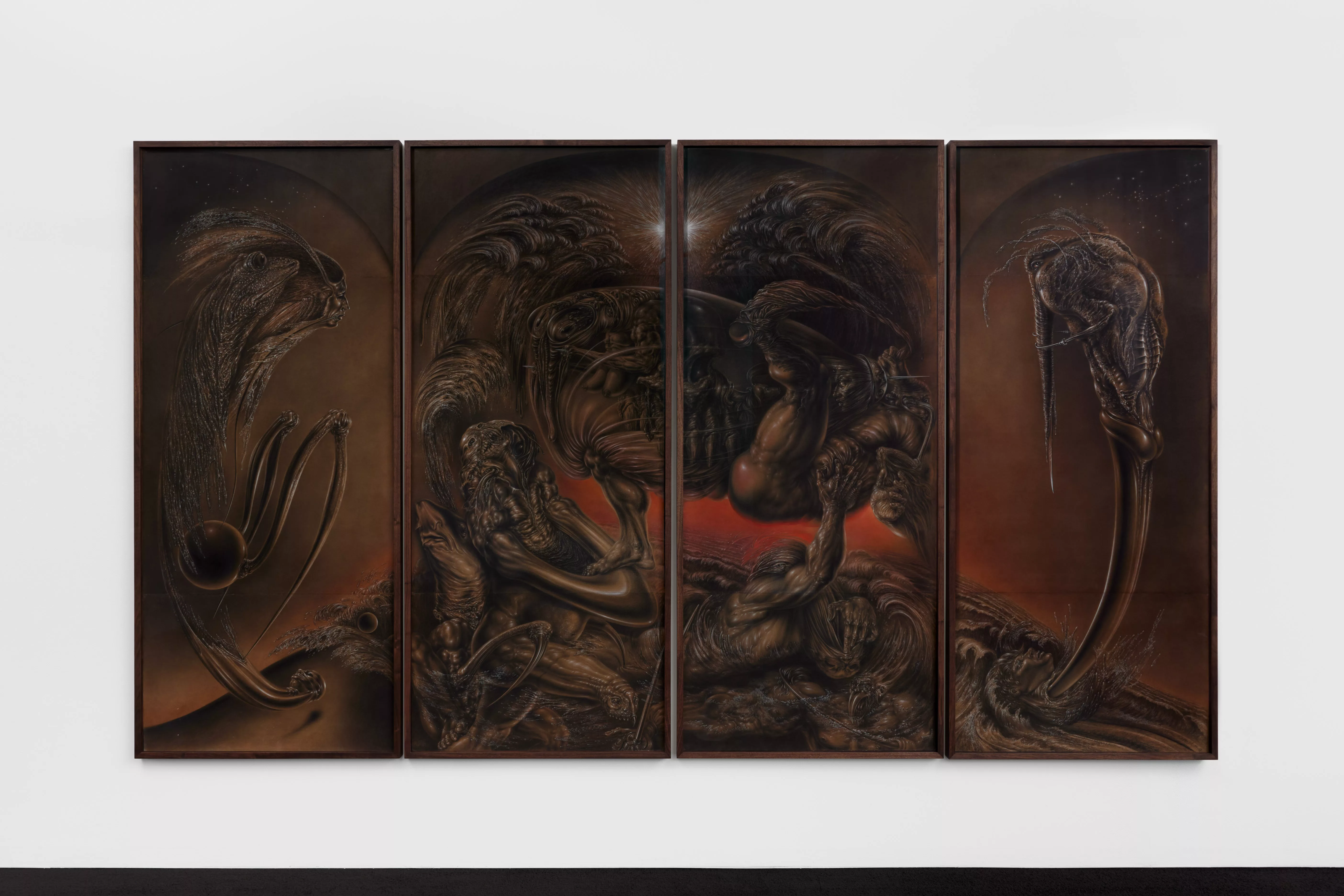

They are also astonishingly skilled; monumental but invariably elaborate, especially the larger charcoal and crayon works on display. The show’s crown jewel is La Bible du Mal (1978), a darkly surrealist Renaissance altarpiece as imagined by the lovechild of the Marquis de Sade and Georges Bataille. It is a frenzy of tight, writhing flesh: a prickly-spined, bird-like figure, with a beak like a plague mask, grows from a long phallus, whilst nearby, two small, droopy breasts protrude from beneath muscular arms and the oversized eyes of a fly. It flits between the imaginary and recognisable symbols: those of art and stories, like the sculptures of Michelangelo or Comte de Lautréamont’s Le Chants de Maldoror (1868). This is the stuff of nightmares and sex dreams in all of their untethered glory.

Ruppert’s only retrospective was in 2010 at the museum of H.R. Giger, her better-known male contemporary. Both of the artists’ practices are concerned with the biomechanical and fantastical, but it is poignant that Ruppert’s is often notably gender amorphous and sometimes rather camp: Pour l’Anniversaire de BA (1978) depicts the bare backside of a mutated man in chaps; leather and kink-wear appear repeatedly in ‘Frenzy of the Visible’. The link between SFF and sexuality has been historically male-dominated (think bouncy-breasted video game vixens and monster dicks), despite many of the genre’s prominent cultural contributions being made by women, such as Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s Frankenstein, or, The Modern Prometheus (1818), and the literature of Margaret Atwood and Octavia E. Butler. If Ruppert’s work– undeniably more shocking, sexy and subversive than Giger’s– could go overlooked in favour of her male contemporaries for so long, it serves to wonder what else has succumbed to the eye of the patriarchal Western canon.

In its second space, Project Native Informant continues its reclamation of the SFF genre by exhibiting four feature films made by Shu Lea Cheang, the Taiwanese-American sci-fi director and pioneer of New Queer Cinema, whose practice spans eco-cybernoia, cyberpunk porn, and the foregrounding of pleasure. It’s an interesting format for a contemporary art gallery: the movies are screened on a schedule, each around an hour and a half long. Sitting in the dark, red-carpeted room on a clear inflatable pool chair (with accompanying plasticky smell), I feel like I’m in the dungeon cinema of a dominatrix, particularly because of the explicit nature of the films. Watching porn in an art gallery is an odd but enjoyably subversive experience. This was the distraction I was looking for when I came here.

Cheang’s films are sensory explosions of defiant anarchism and eroticism, laden with as many literary and other wide-ranging references as Ruppert’s drawings. FRESH KILL (1994), her first film (and her tamest), is the story of a lesbian couple situated in post-apocalyptic Staten Island, being slowly poisoned by a domineering transnational consumer culture in a world of displaced nuclear waste, cyber-activism and environmental racism. UKI (2023) might have been made almost two decades later, but Cheang’s fixations have not been resolved; it is set in a post-internet world in which bioengineering schemes aim to commodify sexual pleasure. Described without their ecstatic visuals and eroticism, these ideas don’t actually seem too far-fetched. In fact, some are already happening to an extent, just perhaps not quite in such graphic ways. As FRESH KILL revolves around the all-consuming power of multinational corporations, as perpetuated by the media, Cheang’s own biography engages with the same concerns. From 1981 she was a member of Paper Tiger TV, a video collective which works to expose the corporate control and subsequent homogeneity of mass media. In a 1996 interview with BOMB magazine, she said of FRESH KILL: “People say the film is futuristic. It’s amazing. It’s happening now, right next to you. What’s futuristic about it?”

The scholar and critic B. Ruby Rich, who coined the term New Queer Cinema, describes it as the foregrounding of “pleasure, ambiguity, radicality and fluidity, rejecting heteronormative representation and assimilation politics.” If this is the case, SFF is game. In SFF, bodies and identities are mutational, fluid things. This is the juxtaposition of the genre: though it is speculative, is fluidity and malleability not the reality of bodily existence? SFF, as well as its confluence with sex in Cheang’s filmography, is also pertinent to our developing understandings of identity, particularly with regard to the digital/physical divide.The transposition of the physical into the digital doesn’t seem nearly so impossible nowadays as it may have seemed even at the time of FRESH KILL. I think of a quote from Legacy Russell’s Glitch Feminism (2020), which argues for the embrace of the internet as a less gender-binary space than the world AFK (away from keyboard). Russell reverses Simone de Beauvoir’s quote “one is not born, but becomes a woman” to “one is not born, but becomes a body”. The revised phrase could easily be applied to various iterations of SFF.

After leaving Project Native Informant, I bought myself a copy of the speculative author Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction (1988) and sat down to read. The essay is a retelling of humanity, redefining technology (and the ‘story’), as a cultural carrier bag. Seen as a container, Le Guin argues, science fiction can be a “far less rigid, narrow field, not necessarily Promethean or apocalyptic at all, and in fact less a mythological genre than a realistic one. It is a strange realism, but it is a strange reality”. SFF may be speculative, but it is no less resonant. In its speculation, it speaks to the visibility of non-normative identity, showing– as the scholar Alison Waller explains– things not “how they are” but “how they are not”. Through envisioning new or alternative forms of existence, we may reconstruct our own.

Written by Ella Slater

Sybille Ruppert’s Frenzy of the Invisible and Shu Lea Cheang’s Scifi New Queer Cinema are on view at Project Native Informant until 20 April

find out more