In March, Billie Zangewa woke up to find she was the only guest left at her hotel in Paris. She had just opened her solo exhibition, Soldier of Love, at Galerie Templon, when overnight the lockdown was announced in France. Her works came down, her show went online and she flew back to quarantine in Johannesburg. The experience brings to mind her work, Christmas at the Ritz (2006), a languid, dreamlike tapestry in which the artist slumbers on sumptuous sheets, made more so by the silk they’re rendered in. The solace of the hotel room conveyed in this private feminine fantasy feels different now.

Born in Malawi in 1973, the artist originally moved to Johannesburg to pursue her career (which has included, but hasn’t been limited to, working as a model, a fashion assistant and in advertising—a training that adds up to what she calls her “MA in life”). Now she steers away from fashion, “when it becomes too superficial… I’m definitely not a fashionista”, she tells me on the phone, and stays in her adopted city for love. Love is the energy that emanates from Zangewa’s carefully sewn and stitched signature collages in scraps of silk, a material she uses because it represents transformation.

“I’m going to have a romantic affair with myself. Society teaches us as women to be ashamed about ourselves, to feel self-loathing”

Home, too, is a site of transformation. A new work, Heart of the Home (2020), currently showing in New York at Lehmann Maupin, depicts the artist in her kitchen, homeschooling her eight-year-old son; at the end of the school day, Zangewa’s kitchen table becomes her studio space once again. Zangewa reclaims the kitchen as a place of fundamental creativity, freedom and familial bonding. It chimes perfectly with her idea of “daily feminism”—humble acts seen as political gestures that shouldn’t be overlooked.

“What happens on the home front is incredibly important to how society functions,” as Zangewa puts it. The innocence and quiet harmony of the double portrait Heart of the Home contrasts with a new solo portrait of her son Mika, an image Zangewa made while “looking at him and the miracle he is, but also thinking about his identity as a male who is half black and what that will mean. I was coming from a complex place, psychologically, making that work, with the worry of a mother about her child who looks a certain way and how it’s going to go for him.”

- Left: Heart of the Home, 2020 Hand-stitched silk collage. Right: Everyday Miracle, 2020. Hand-stitched silk collage. Both courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, Seoul, and London

Audre Lorde posited that “only within a patriarchal structure is maternity the only social power open to women”, and Zangewa picks up on this idea of what women’s innate power might be. The transformative nature of nurturing is what propels Zangewa’s new group of works, made during lockdown about her experiences during this period. She has titled the resulting exhibition Wings of Change, and it is her first solo show in the States. She dovetails self-love, maternal love, romantic love, sensual love—love that endures against the odds; love that isn’t conditioned by circumstances; physical love and love that passes beyond.

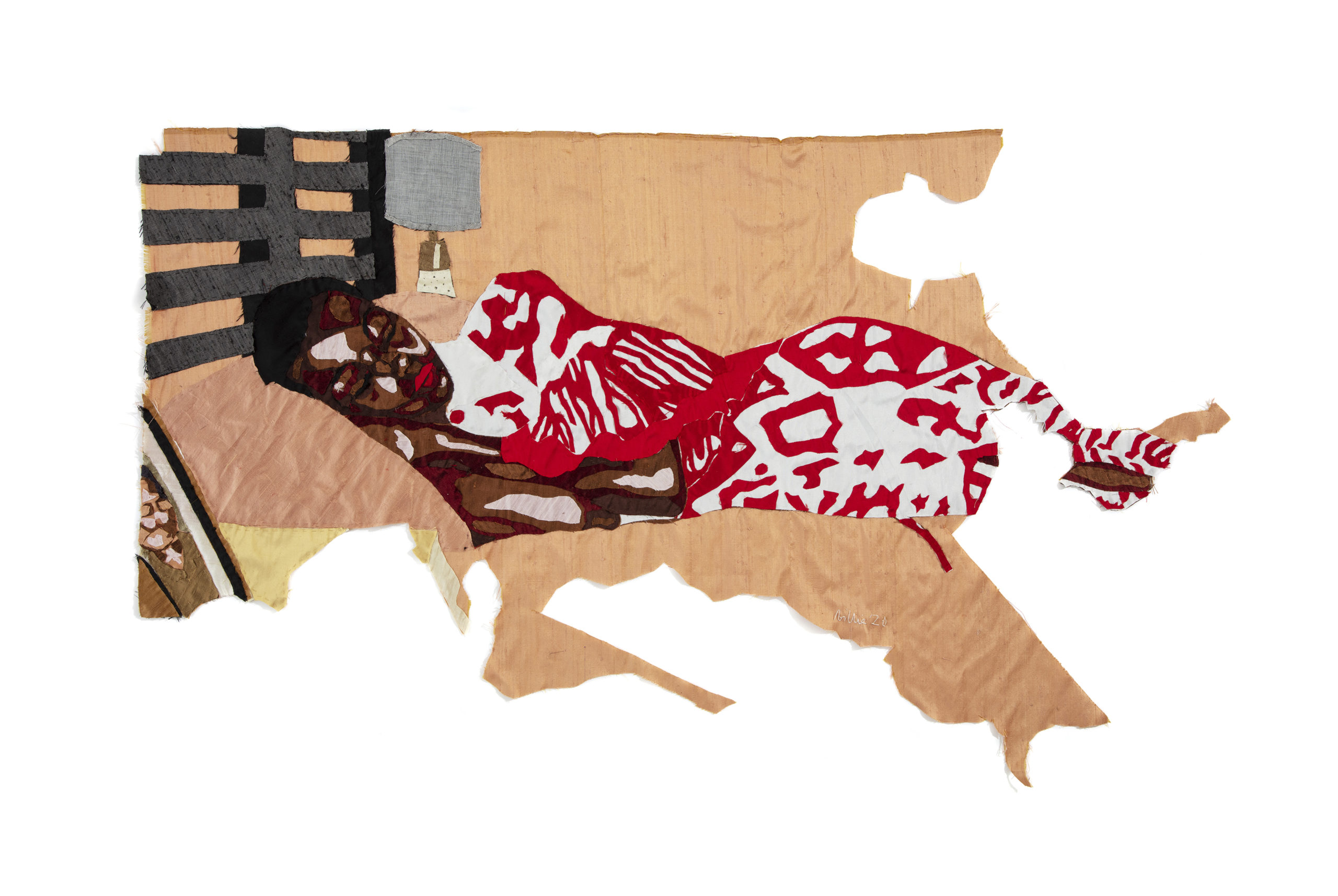

During the pandemic, Zangewa lost her close friend and former lover, Henri Vergon, the founder of Afronova gallery, who died of a heart attack in May. Due to lockdown, she wasn’t able to attend his funeral. Two works in the exhibition deal with his death: Angel at my Bedside, a self-portrait sleeping, speaks of a visitation Zangewa experienced after Vergon passed away. Next to it hangs an affectionate portrait, Vergon dancing in a pink sky, and in the corner of the frame, just visible, is a replica of one of Zangewa’s iconic works, The Rebirth of the Black Venus (2010). “We’re both floating in the air, but he’s on a celestial trip while I’m coming down to earth”, Zangewa reflects wistfully.

While Zangewa’s early silk tapestries were mostly cityscapes, The Rebirth of the Black Venus marked a pivotal moment for the artist as she began to focus more on the inner world, both literally and figuratively. Interior and domestic scenes resonate widely in visual culture, but what Zangewa does so exceptionally is to juxtapose all of the different aspects of the female experience; sexuality, sadness, strength, sensual joy and solitude all meet in these images, her most confident yet.

In these latest pieces, she is entering another phase in her work, particularly in the way she represents herself: “from looking to the outside for approval and to define my value to saying, I’m going to have a romantic affair with myself. Society teaches us as women to be ashamed about ourselves, to feel self-loathing. I’ve put on weight during lockdown, and I’m getting older, but when I look at myself, I think I’m the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen.”

“I’m not trying to do anything grand—they’re universal themes but it’s about the journey home”

Zangewa is attuned to how hard-won this self-love can be. She spent years feeling frustrated: “I was angry with the patriarchy, but that can be destructive for the person feeling it. So rather than saying, patriarchy is terrible, why not centre women in the narrative, and say, women are incredible, they are magnificent, strong and dynamic?” This is channeled into her work that has always centred around Zangewa’s life and everyday.

“I’m reclaiming my identity, my feminine power, and my significance in society at large.” She describes the new works, like

Fresh Start and Heart of the Home, as more “matter-of-fact. I’m not trying to do anything grand, the poses are much easier—they’re universal themes but it’s about the journey home—and home is a place of total self-acceptance and unconditional self-love.”

Femininity and sensuality today are often bound up with capitalism, and embracing this as part of the female experience is one of the quietly radical aspects of Zangewa’s work. As an artist, she celebrates the feminine, and sensual enjoyment; her figures delight in exquisite bedsheets, beautiful clothes, showers and books. This, of course, is what is authentic to Zangewa, and it also creates its own aesthetic pleasure. But it is purposeful joy.

Zangewa frames her femininity within the existing structures of a cosmopolitan, capitalist society, rather than try to deny that women too are agents in it all. Her work is redemptive. This is a radical statement in itself: to prosper in the patriarchy.

It resonates with the words of Naomi Woolf, who in her 1990 book on feminism and commodification, The Beauty Myth, writes; “Let’s be shameless. Be greedy. Pursue pleasure. Avoid pain. Wear and touch and eat and drink what we feel like. Tolerate other women’s choices. Seek out the sex we want and fight fiercely against the sex we do not want. Choose our own causes. And once we break through and change the rules so our sense of our own beauty cannot be shaken, sing that beauty and dress it up and flaunt it and revel in it.”