Whatever the scenario, eating with others is, in a small way, an inherently intimate act. Food is about sharing; it can be messy; it forces interactions—even if they’re as seemingly insignificant as asking someone you’ve never spoken to before to pass the ketchup.

A Cornell University study found that firefighter platoons who eat meals together have better group job performance compared with firefighter teams who dine solo. Kevin Kniffin, one of the authors of the study, stated: “From an evolutionary anthropology perspective, eating together has a long, primal tradition as a kind of social glue… That seems to continue in today’s workplaces.” However stressful their jobs might seem, artists and designers aren’t spending their days fighting fires, but that doesn’t mean many espouse the benefits of communal dining.

Olafur Elíasson, for instance, is famed for his Berlin studio’s tradition of sitting all staff down to eat together each day. The space—which has its own Instagram account—has its very own expansive kitchen which feeds his workers, “apart from Mondays”, he told the Guardian, when they get takeaways or people go out to eat. When the Guardian visited Eliasson’s Berlin space in 2016, the kitchen had been running for ten years, and the cooking team was run entirely by women serving only organic, vegetarian food. Ai Weiwei apparently often popped in from his nearby studio.

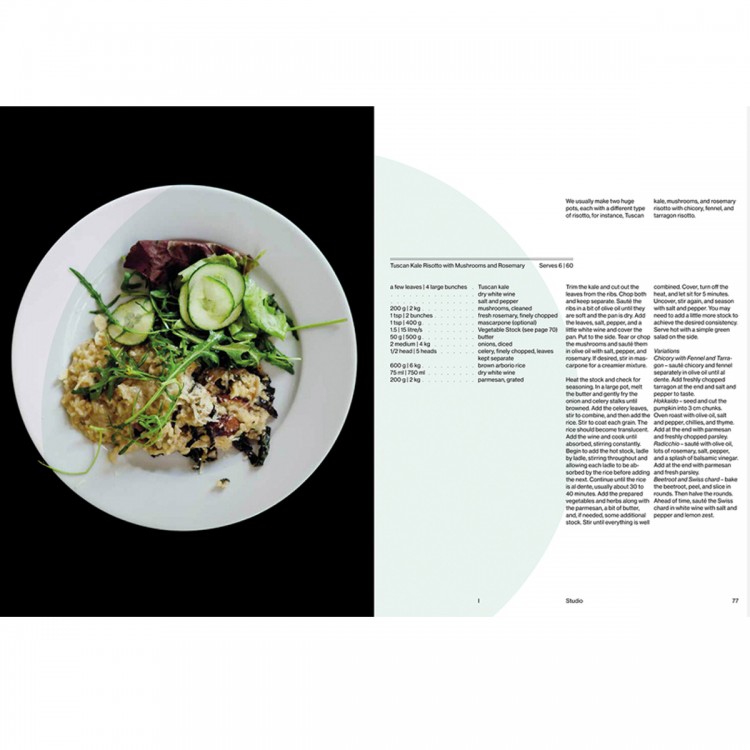

So committed is Eliasson to the art of eating that in 2016 he released a book, Studio Olafur Elíasson: The Kitchen, which shared more than one hundred vegetarian recipes as enjoyed by the artist and his team. He also opened SOE Kitchen 101 last year in Iceland, a three-month pop-up that saw chef Victoría Elíasdóttir and Elíasson create a space he described as being designed for “eating and thinking, for food experimentation and impromptu encounters” inspired by “the menu and the atmosphere of the Studio Olafur Elíasson (SOE) Kitchen in Berlin”.

- From the book Studio Olafur Eliasson: The Kitchen

Design agency Pentagram’s New York office takes a similar approach to communal eating. The studio’s chef, Anne Ferril, has worked there for more than twenty-seven years. The tradition of having a chef at Pentagram started in London, for both practical and cultural reasons: the studio’s location was pretty lacking in places for staff to eat at lunchtime, for one—so people would either have to be organized enough to bring in their own food each day, or spend their entire lunch hour trekking to buy food. But it’s also about Pentagram’s unusual agency structure: it’s split into different teams, each headed by an individual partner, and the teams rarely mix other than occasions like lunch. “Even though we all sit in an open-plan office, our teams often don’t get to spend time with one another because of our structure: each partner has a group that functions autonomously,” Bierut told Eye on Design. “The lunch period provides a chance for everyone to sit side by side. In a lot of companies, that’s usually reserved for special occasions, or as a once-a-year holiday thing, but we do it three days a week.”

Over in New York, Ferril faces the mammoth task of feeding around one hundred people every day; making a hot entree with vegetarian and meat options, multiple side dishes, different breads, exotic cheeses and fruit. Staff often take time out to chatter with her, and help prepare veg—surely a welcome distraction from a design job that’s almost entirely desk and screen-based.

- Left: Anne Ferril, image by Michael Bierut, courtesy of Eye on Design; Right: Lunch at Pentagram New York, image by Anne Ferril, courtesy of Eye on Design

While not many design agencies have the size, budget (or, indeed, kitchen facilities) to work as Pentagram does, it’s not unusual for them to have traditions around communal eating. Kerry Wheeler works at Bristol-based agency Home, where every Wednesday two people from the studio cook for everyone else—usually a main course and a pudding, ranging from “something that you would get in a pretty high-end restaurant, to a full English fry up”, says Wheeler.

“Eating together has a long, primal tradition as a kind of social glue”

The agency produces the budget, and the cooks are appointed via a rota system. “We always mix it up with people from different departments—account managers cooking with designers, production team members cooking with strategists, managing directors cooking with juniors,” she adds. “The most important thing is that it gives us a chance as a company once a week to all come together, regroup, catch up and spend a bit of time in each others’ company. It brings people together, it breaks down barriers, and when that bell rings or the shout out goes out across the studio to say that lunch is ready, the morale lifts and it brings a little bit of joy to our days and sometimes our weeks.”

Food also plays a huge role at New Zealand design studio Alt Group. A Creative Bloq piece in 2014 reported that designer Aaron Edwards makes lunch for everyone, every day (unless he’s not in, in which case someone else does it), and all staff eat together. Edwards had been doing that for the past fourteen years, rustling up anything from chicken with rice and salad to oriental noodles with seafood, roast lamb or soup. The idea is to make the company culture more like a “family” (a comfort to some, a notion that might make other personalities shudder).

London-based studio Hato, too, sees the sharing of food as integral to its wider co-creation approach that it applies to all of its work, internal and external—in part, inspired by founder cofounder Ken Kirton’s Japanese ancestry. “It’s a very community-centred society,” Kirton, told us. Hato staff take it in turns to cook lunch for the rest of the studio every day. “Lunch is a social interaction, and there’s a sort of art or symbolic element to cooking for everyone and sharing from the middle of the table,” says Kirton.

Studio DR.ME moved into an eleven-person shared studio in Salford 2016. “We all fell into a habit of eating at our desks, partly just due to there not being enough space anywhere else as every inch is occupied by desks, plan chests, risographs, sewing machines etc,” says co-founder Mark (Eddy) Edwards. When their friend’s framing business downstairs moved out, they decided to make it into a communal space, with their friends from graphic design agency Textbook Studio and illustrator Paul Hallows making some long Enzo Mari tables from scratch so that the studio could all eat together. “Slowly but surely we’ve started having ‘Lunch Club’ together around midday,” says Edwards. “Although it does feel occasionally like a bit of a distraction when you’re busy, it’s always really nice to just enjoy the company of the others in the studio and catch up with what everyone is up to. It’s certainly not enforced on people and because a lot of the time our timetables differ, and it’s not always possible, but when it is it certainly has a really positive effect on the vibe in the studio.”

“Although it does feel occasionally like a bit of a distraction when you’re busy, it’s always really nice to just enjoy the company of the others”

Often when you’re eating with colleagues, chat in this supposed “downtime” can easily turn to work, but Edwards says that midday is mostly just about “inconsequential chat”. He adds, “We’re all friends so it just depends on whether the conversation drifts that way, imagine you were in the pub with mates, it’s that kind of flow of conversation. But if someone has an exciting project on the go or an issue with a problem in their practice then we’ll talk about that.”

- Jonny Costello and Adult Art Club, lunchtime at Kanteen in Digbeth.

Perhaps one of the reasons so many design studios are keen to lunch together reflects wider changes in the industry. In the nineties and early 2000s, such agencies were generally pretty boozy: client meetings were often lubricated with alcohol, liquid lunches weren’t unusual, colleagues met in the pub after work. That seems to happen less and less now: maybe a nice lunch is the new piss-up?

Jonny Costello of Birmingham-based creative agency Adult Art Club used to work at an agency that “never went for a drink or socialized together”, and so saw their regular Friday lunches out together as a positive thing (these were very much encouraged from those at the top, but people had to pay their own way). “Everyone in the studio has quite busy lives so that slightly less formal social atmosphere as opposed to intense work all the time,” he says, “I do think it’s a positive thing, especially for new people to pop that social seal and build rapport.”

Now at a much smaller studio, he makes sure to meet up with local freelancers and get out the studio to eat each day. “We don’t really talk about work, and when you work from home a lot of the time it’s a nice way to get out and do a bit of socializing. I understand some people might have a bit of resistance to that sort of thing, but you have to remember everyone’s human—they all have their own shit going on.”

DR.ME reckons there are no downsides to the arrangement, but for some, lunchtime is an opportunity for a bit of alone time; a chance to go for a walk, pause, and take just a few minutes to get away from work. Maybe that’s an antisocial view of things, but—especially when you’re new at a job—eating in front of people, for some, can feel a bit scary. I for one actively avoid lunch meetings with PRs and the like and opt for coffee: who can really talk properly with a mouthful? What if I spill something on myself? What if I get something in my teeth and no one tells me?

I wonder with places like Eliasson’s studio what it must be like if, say, you simply don’t like what’s being put in front of you that day—memories of the “clean your plate” sternness of school dinners spring to mind. When I worked at It’s Nice That we had a lovely tradition each month of working in teams to cook for the rest of the studio, which is split across the editorial platform and its sister creative studio. It was a nice opportunity to work and sit with people you don’t usually. But on a personal level, I felt a sense of awkwardness: I’ve been vegan for the past thirteen years—yes, that’s right, before it was “cool”—and against all inherited vegan-bashing gags and memes, I don’t like to talk about it. In the early days, that was for fear of looking like I was either bonkers or a pain in the arse; now, it’s to avoid being lumped in with the smug Instagram wellness brigade. When you’re sharing a meal with people who for the most part aren’t vegan, you’re throwing a spanner in the works. Though no one made me feel this way, I did have a certain guilt that I was being the “difficult” child, quietly asking if things we’re being fried in butter or not.

“Anything ‘enforced’ in an agency environment scares me”

For Eliasson, the idea of sharing a meal with his team (and a few visitors) is about sharing ideas as much as food—it forces people to leave their segmented departments and come together. “The kitchen is a nice leveller,” as he put it. On a more shrewd level, he sees the sort of food he serves—organic, vegetarian, heavily plant-based—as a way of keeping staff healthy. In other words, they’re less likely to have sick days.

Indeed, while Eliasson’s kitchen feels undoubtedly like a joyful, and generous thing; communal eating also has its savvier side. I’m always suspicious of the likes of Google and their “perks”: the whole “hey, guys, have some free beer! Use our sleep pods! Meditate! Here’s a gym pass” smacks of an environment where you’re surreptitiously being told that you’ve no real need to ever actually leave work—that enforced health policies might just be there to make you fitter, happier, more productive.

Dave Sedgwick, of graphic design agency Studio DBD, is also suspicious of the idea of rules around lunchtimes. “I guess anything ‘enforced’ in an agency environment scares me,” he says. “I think if something like a lunch happens organically or by choice then that’s fine, it’s just I am not a fan of the notion of forcing people to do anything they might prefer not to do! Maybe I’m just old and grumpy though.”

“I’ve worked in places that have made you feel guilty for going home at a reasonable hour or not socializing in your free time with your workmates,” he continues, “to me it’s often a way to create an atmosphere where you are expected to constantly be at work. There’s a fine balance, getting along with your work colleagues is great and important for creative work output, but you also need your own space and time. I often enjoyed the lunchtimes away from the studio, a chance to recharge and get some fresh air. I now work alone. Maybe this is why!”