It’s not long after arriving in Salisbury that the Cathedral can be seen rearing its Gothic head, its pointed spire piercing the clouds, looming over the medieval city. It is in this hallowed space, perhaps best known for its copy of the Magna Carta, that Shezad Dawood’s installation, Leviathan, is exhibited. The works on display form part of several larger bodies of work by Dawood, including an ongoing multi-disciplinary project (also entitled Leviathan) centred around the connections between the climate, migration, and mental health. Across the space, Dawood’s paintings, sculptures and films become touchstones on an experiential procession between the pews, around the altar and towards the Magna Carta.

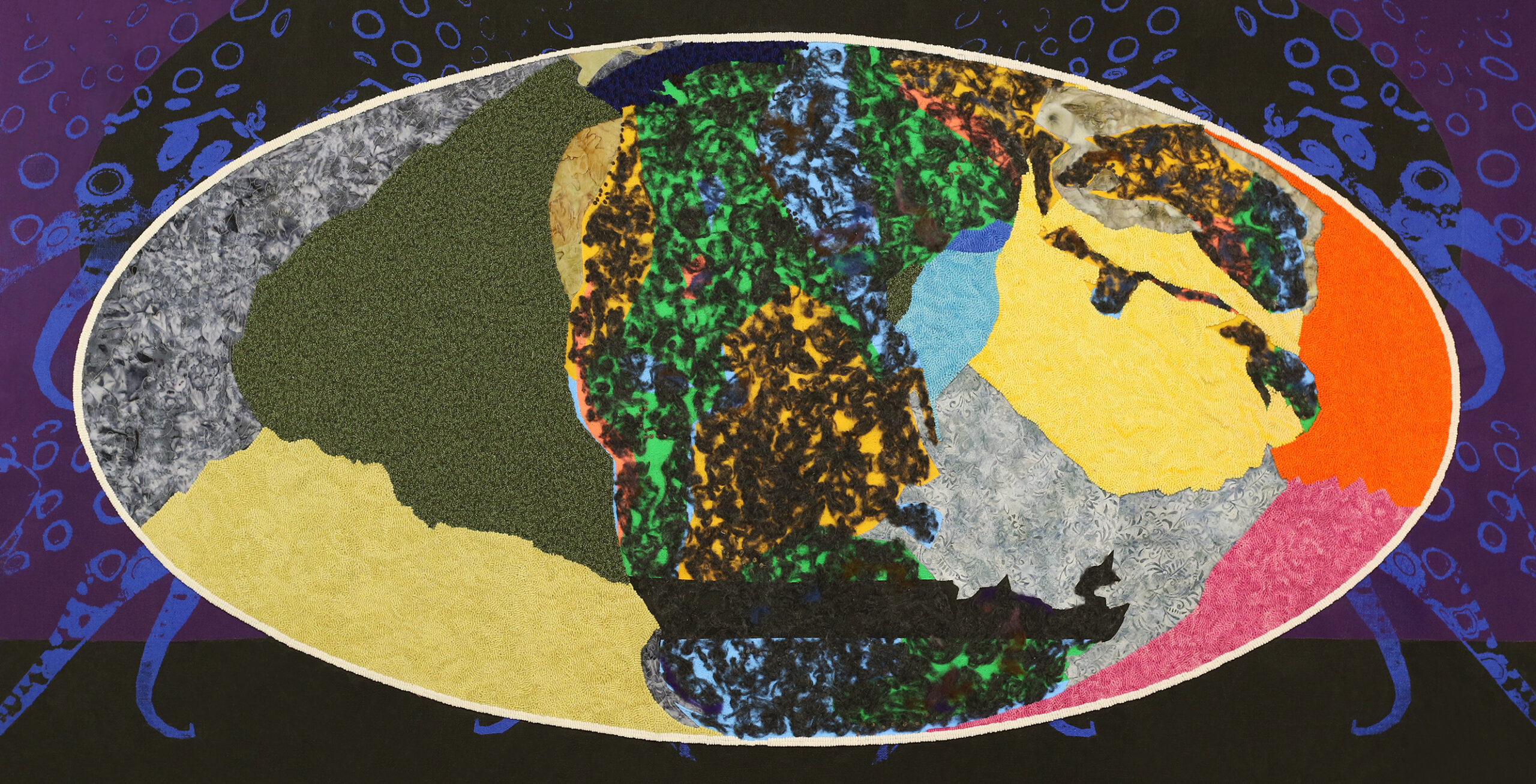

Suspended above the nave – the central passage near the pews – are selected pieces from Dawood’s Labanof Cycle, a series of earthy, tonal paintings on textile depicting seemingly ordinary objects, a student ID card or USB stick, for example. These objects represent possessions lost by migrants and refugees on their journey between North Africa and the island of Lampedusa in Sicily. This project was originally born out of Dawood’s conversations with Cristina Cattaneo of ‘Labanof’ (Laboratory of Anthropological Forensics) at the University of Milan. Labanof works both to identify dead migrants and to retrieve and catalogue the lost possessions of those who attempted to cross to Lampedusa. After visiting Milan and the Labanof archives for the first time in 2016, Dawood began to paint these objects. The final textile paintings feel like objects in themselves; the faded nature and muted colours serve to weather the paintings – communicating the journey not only of these lost objects but of their owners too, a life lived and hoped for. Labanof Cycle is at once immense, affecting, and yet subtle, as the works echo the aged, worn architecture of the Cathedral. In this context, the Labanof Cycle assumes new meaning. All around these paintings, the walls and floors hold memorials, tombs and epitaphs memorialising heroes, saints, and victims of natural disasters. Not only do Dawood’s paintings highlight the difficulties of memorialising migrants, but they also serve as an alarming reminder of global apathy towards refugees whose humanity is too often not acknowledged. Labanof Cycle was originally displayed at the Venice Biennale in 2017, and has been in numerous locations since. Through the continued re-display, Dawood reminds us that this is a global problem, not isolated to Mediterranean seabeds or to the work of Labanof, but relevant even in landlocked Salisbury.

The dangers of crossing and lack of empathy reappear later in the Cathedral with Dawood’s Where do we go now?, a digitally rendered sculpture inspired by Jonathan Swift’s A Tale of a Tub, itself a satirical response to Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan. The sculpture depicts sailors throwing a barrel, or a ‘tub’, off a ship to distract a whale, which Dawood aligns to the ‘Beast of State’. The sailors in Dawood’s ship are joined by two migrants and a UN refugee worker in protective clothing. As you circle around the phantasmic sculpture, it begins to mutate as the light shifts throughout the day. Within minutes, it can transform from an inky, oily black with hues of green to taking on a more futuristic purple glow, an effect achieved by Dawood’s use of ‘polychromatic paint’, a medium which the artist first displayed at his 2014 exhibition at Parasol Unit. This technique creates dynamism; the sculpture refuses to be static and passive and demands that you watch the scene – the intensity of the waves and the monstrosity of the beast.

Where do we go now? is located adjacent to the Cathedral’s original draft of the Magna Carta, a document which endures in the public imagination as a guarantee of citizens’ rights. Dawood is making a clear statement, not only concerning the perils of the dangerous conditions of refugees’ migration but on whose citizenship is valued by the ‘Beast of State’ he depicts. For Dawood, the ‘tub’, or barrel, thrown overboard by the sailors in Swift’s story, represents labour and capital. Perhaps then, the ‘tub’ thrown overboard by the refugees is a nod to the risk of forced labour and the ways in which migrants are increasingly measured by their financial contribution and ‘skilled’ labour potential.

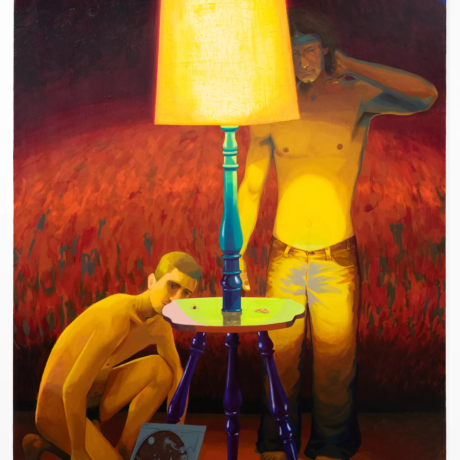

From this harsh and inhuman present, the question ‘Where do we go now?’ is best answered in the film works presented in Salisbury. Exhibited here are the latest episodes (7 and 8) of Dawood’s ongoing ten-part film project, Leviathan Cycle. Episodes 6-10 of Leviathan Cycle are set in the not-so-distant future, in 2050. Dawood’ futurecasts’ these films. That is to say, his co-authors and participants are asked to imagine the future and the world we might come to inhabit – they are thus ‘casting’ their future selves.

Episode 7: Africana, Ken Bugul & Nemo, set in Senegal’s capital Dakar, weaves together footage of the natural environment, and ‘futurecast’ testimonies to a background of narration and rap. Some hazy clips of the ocean and scenes almost feel nostalgic, a jarring feature in a film reaching into the future. This contrast evokes an almost ‘slippery’ feel to the film, as though it defies the categorisation of past, present, and future and instead folds these eras together into fleeting, varied scenes.

The film foregrounds the mangrove ecosystem in the coastal city of Dakar; glistening clips of the mangrove nod to the fantastic plant which protects coastal communities and captures carbon. This footage is overlaid with the testimony of lawyer and community organiser Africana who, in 2050, prioritises community wellbeing and discusses how earlier developmental ideologies have advanced: ‘petrol can’t lead to development’. While Africana never speaks explicitly of the mangroves themselves, her criticism speaks to policies of extracting natural resources for economic development, which are often backed and funded by foreign governments and institutions like the IMF and World Bank. In Episode 7, this leaves the mangrove tree behind as a symbol and solution to creating community-led and ecologically respectful climate futures.

Part of this future involves broader change. In a jewel-toned blue dress, sitting on a flimsy chair on the sandy beaches, future cast writer Ken Bugul powerfully claims that ‘in 2050 we will find ourselves to be naked… ‘it’s a process of mental, intellectual, spiritual, material nudity.. To return to the original body’. This nudity speaks to a stripping, a reversal, even, of Western structures of knowledge, of colonial and neo-colonial logic. Dawood’s editing together of everyday ecological scenes and melding together of present and future evoke the community-based, decolonial, and nature-led solutions to climate change and its impacts, which are vital in vulnerable places like Dakar. The rhizomatic structure of the mangrove ecosystem becomes a metaphor for thinking through these possible futures; environments, climates, places, and communities are generative and messy but, above all, interconnected.

Episode 8: Cris, Sandra, Papa & Yasmine in the Trinity Chapel space of the Cathedral. Like Episode 7, the film foregrounds a particularly powerful natural environment, in this case, the Brazilian Atlantic Forest, one of the richest and most diverse areas on the planet.

The film then tracks the path of the indigenous Guarani that links the forest to the sea, beginning with disorientating choppy clips of the Atlantic Ocean, multiplied and overlaid, before settling into the beauty of the waves and the clarity of the water. The camera slowly pans over the forest. The light flickers as the scenes of the forest slowly transition in and out of each other. These scenes are interposed with animations by co-director Anita Eckman – initially of strange forms, as though under a microscope, and then turtles, owls, and butterflies. These creatures take on multiple meanings – perhaps a nod to the spiritual significance of these animals or even a reflection of animal populations at risk through the ongoing destruction of the forest. The film was developed remotely in collaboration with indigenous Guarani scriptwriters, directors and activists Carlos Papá, Cristine Takuá, Sandra Benites, and Brazilian artist and researcher Anita Ekman, who filmed this episode for Dawood to edit. This horizontal co-authorship and collaborative process enables Dawood and his collaborators to illuminate indigenous ecological cosmologies which promise healthier co-existence, indeed entanglements, between people and forest.

In many ways, Shezad Dawood’s Leviathan at Salisbury Cathedral speaks to the artist’s ever-expanding practice: collaboration with marine biologists and indigenous activists, diverse visual media from screenprinted textiles to digital sculptures, and experimentation with dichroic paints. Each medium and collaboration is carefully chosen by the artist to communicate his expansive but vital ideas. Dawood’s practice goes beyond his artistic output; using funds from his Studio, the artist is funding grants for doctoral candidates and post-doctoral researchers at the Australian Institute of Marine Science – a testament to his commitment to drawing art and research together to find solutions to pressing global issues of our present and future.

Words by Vaishna Surjid