In 1962, the burgeoning art department that Sister Corita Kent ran at the Catholic Immaculate Heart College on Los Angeles’ Franklin Avenue had outgrown itself. The productivity and popularity of the ‘Pop Art nun’ necessitated the addition of ‘her’ studio: in theory, a collaborative art-making space, in actuality a room where her working practices led the cohort and the results adorned the walls.

The utilitarian concrete-block double storefront, which for the previous 30 years had housed a dry cleaning business, was granted Historic-Cultural Monument status on 2 June 2021 as the space in which Kent produced “the body of work that establishes her as a major, and uniquely significant, figure in the history of Pop Art.”

Also in 1962, Kent is believed to have discovered Pop Art at a show of Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans in LA’s Ferus gallery. Critic Susan Dackerman inverts the usual explanation of how the influences flowed, describing Warhol as “then a little-known commercial artist from New York,” while Kent was “a nationally recognised artist, with her prints appearing in exhibitions across the country”.

Dackerman records how a fellow nun, having travelled with Kent to the opening of one of her annual winter exhibitions at New York’s Morris Gallery, wrote that “the opening is crowded with her fans. Andy Warhol is there (He would be captivated by the idea of an artist-nun, especially one who uses Wonder bread wrapping as a symbol for the Eucharist).”

“The massive liquified natural gas tank she adorned with the ‘Rainbow Swash’ is still the largest copyrighted artwork in the world”

Warhol’s ‘captivation’ with Kent’s prints reflected both his devout Catholic faith and the subject matter of his own art, which scholar Eugene McCarraher has described as a celebration of “the humble matter of everyday life, a realm where, in Orthodox tradition, the divine always manifests itself sacramentally.” Kent similarly believed that Pop artists “work with the same stuff artists have always worked with, the stuff that is around them.” Making Pop Art was a process not just of transformation but of transubstantiation. “By taking bread out of its ordinary form and presenting it as his body, He [Christ] originated Pop Art,” Kent wrote.

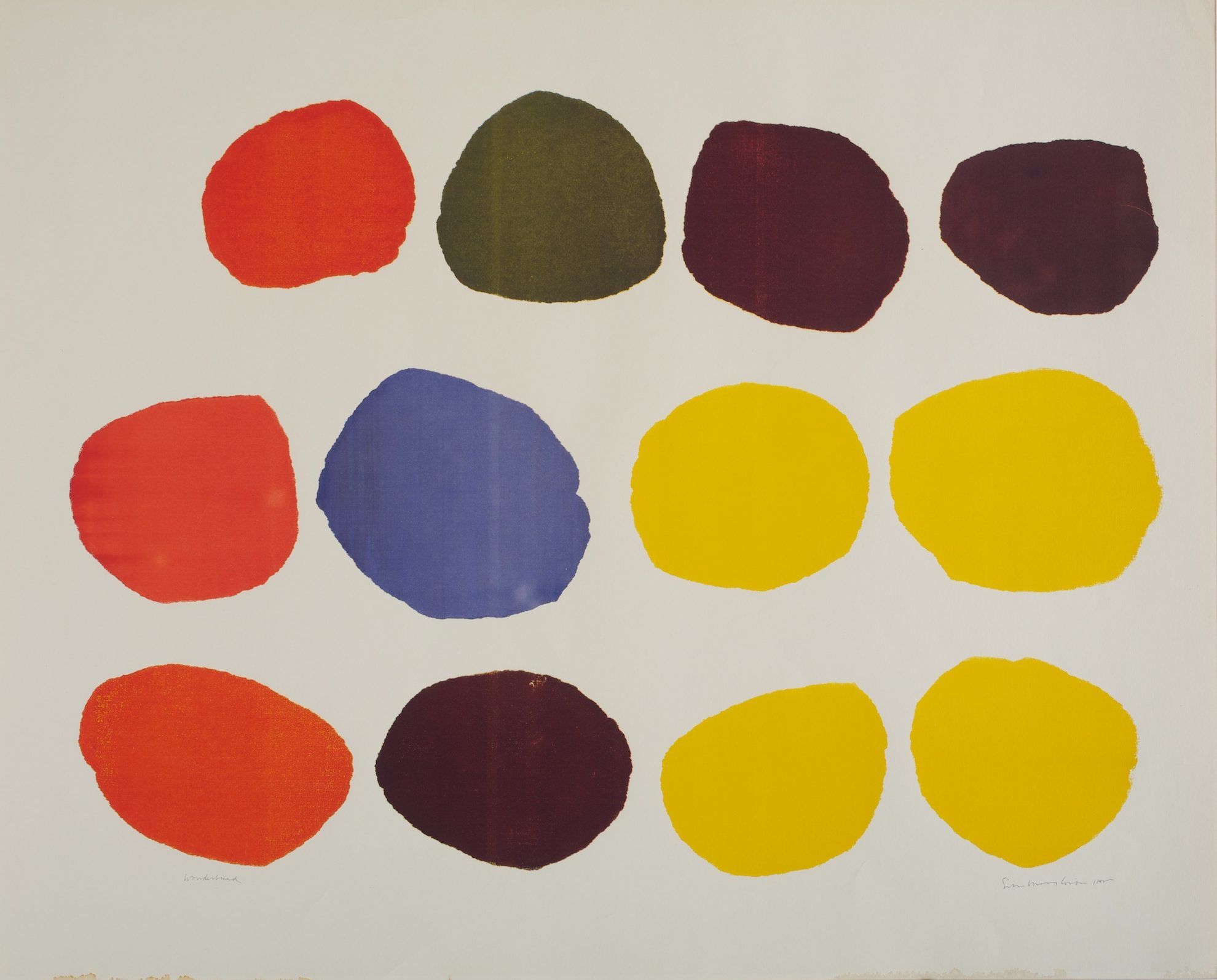

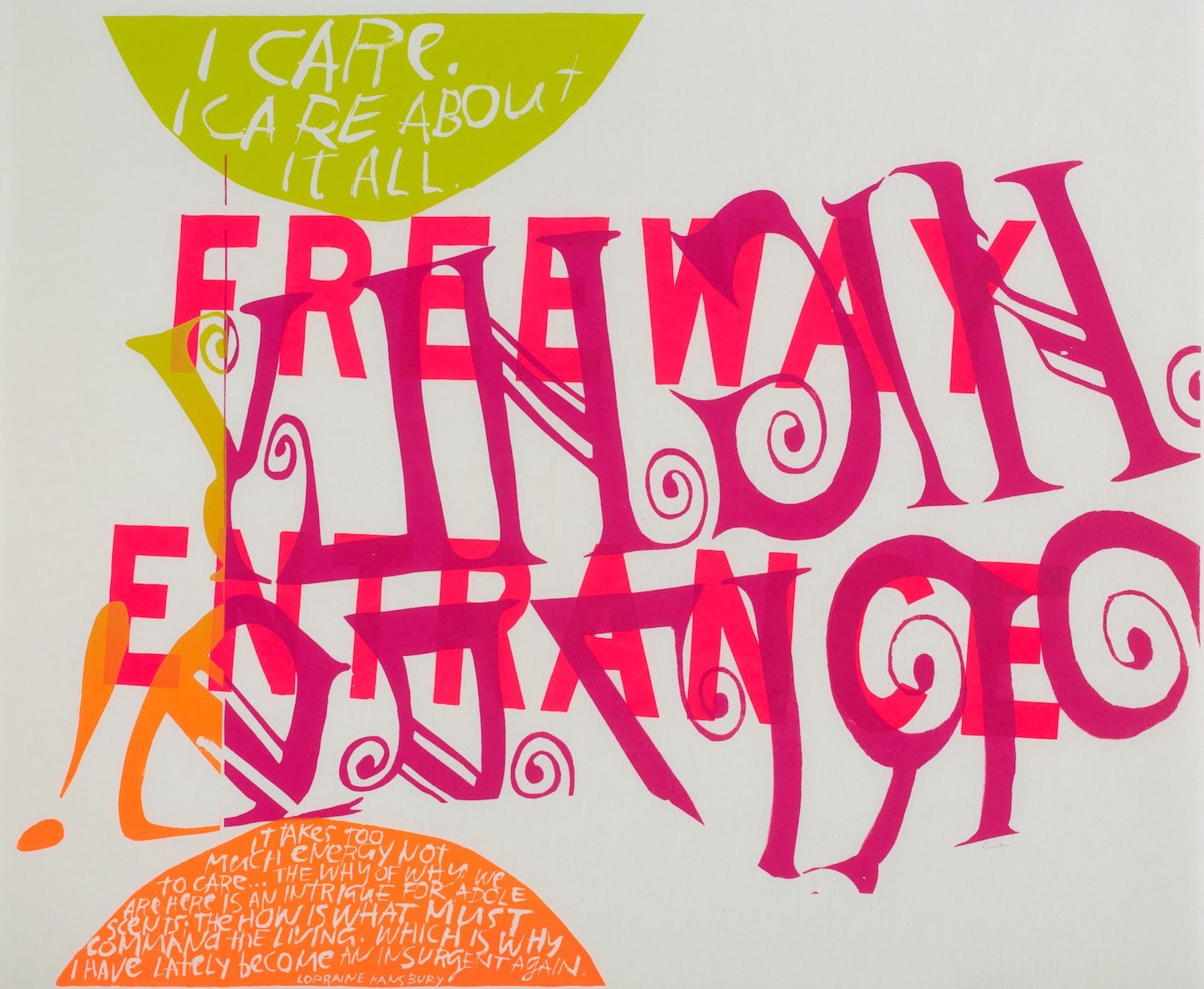

In the piece round wonder

, one of Kent’s series of screen prints that appropriated the logo and colours of Wonder Bread packaging, the two words are seen within, and through, a roughly circular shape that represents the communion Host, evoking both the religious significance and the social value of bread. The Wonder of a mass-produced supermarket product merged with the wonder of Christ.

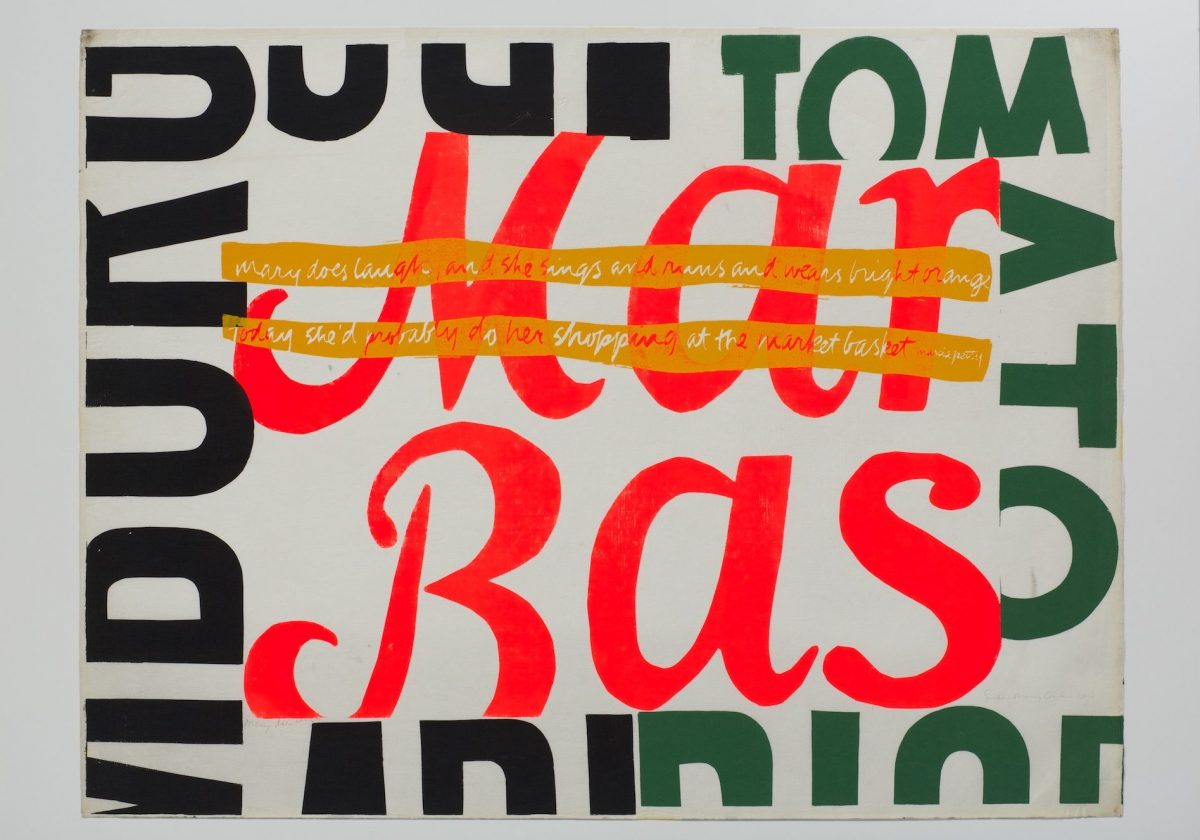

Bread connected the opening of the Market Basket grocery opening directly across the street from Immaculate Heart College in 1963, and the liberalising pronouncements of the Second Vatican Council the same year, which included the right to the means of life, “particularly food”. “Groceries”, Kent declared in her ecstatic, epiphanic way, “became a revelation.”

She shared the practice of appropriating the imagery, iconography and language of consumer products with several contemporary artists, many of whom were featured in another show she saw in September 1962: New Painting of Common Objects

, at the Pasadena Art Museum. Warhol featured, along with Roy Lichtenstein, Jim Dine, Wayne Thiebaud and Ed Ruscha.

“Kent’s art deployed the vernacular visual language of her time to simultaneously liberate and reaffirm faith”

A year later, the same gallery hosted a Marcel Duchamp retrospective, his concept of the readymade reaffirming the artistic validity of the ordinary object. LA was experiencing a cultural explosion. Pop Art was the driver and the art department at Immaculate Heart College became one of its epicentres. Its annual art fair took the form of an avant-garde ‘happening’, attracting Kent admirers including John Cage, Ray and Charles Eames, Alfred Hitchcock and futurist Buckminster Fuller, who called it “one of the most fundamentally inspiring experiences of my life”.

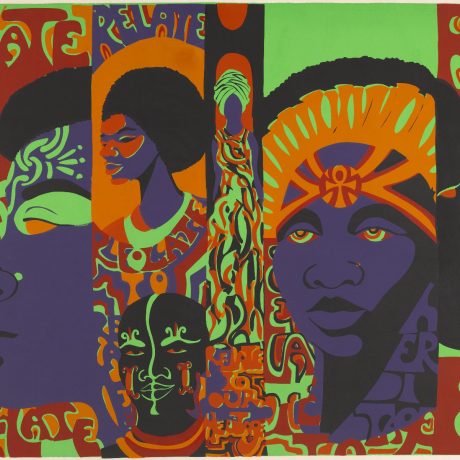

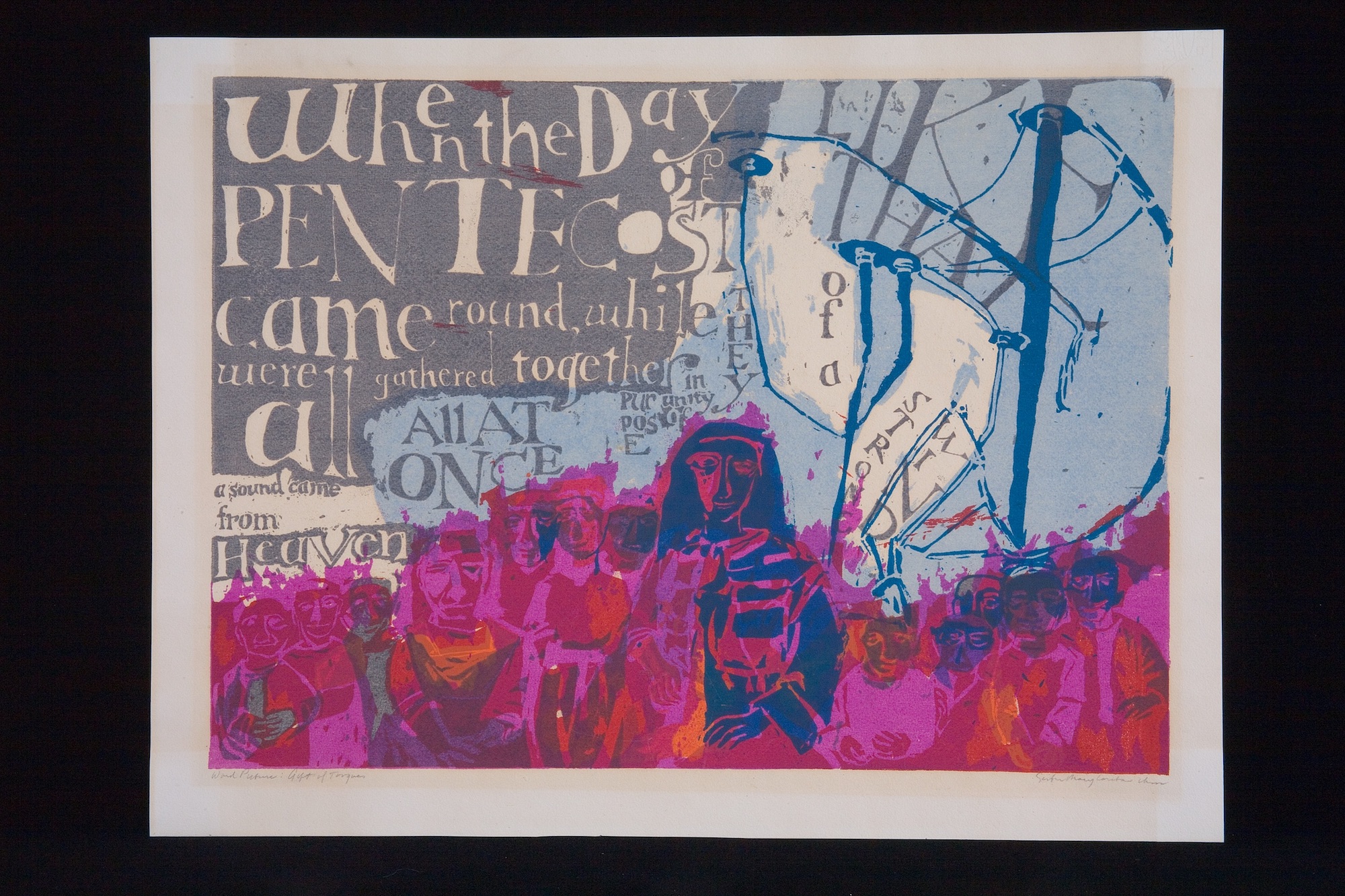

word picture: gift of tongues, 1955. Courtesy Corita Art Center, Los Angeles

Kent roamed the Hollywood streets with a pack of students, selecting views through a cardboard frame, spending afternoons in the gallery quarter around La Cienega Boulevard, and taking hundreds of photographs. Making serigraphs in the college workshop with the help of students, fellow nuns and volunteers, she insisted on ‘pulling’ the prints herself. Production at populist scale became her hallmark; her LOVE stamp for the US Postal Service sold 700 million copies, her ‘Rules for Artists’ poster was in every studio, the massive liquified natural gas tank she adorned with the ‘Rainbow Swash’ is still the largest copyrighted artwork in the world and an enduring Boston landmark.

While her art delighted the public, it had the opposite effect on the conservative archbishop of Los Angeles, Cardinal James McIntyre. His impatience with the Order and its melding of Sixties counterculture and religion condensed into outrage with the issuing of Kent’s 1964 print, The Juiciest Tomato of Them All, which compared the Virgin Mary to the ripe red fruit. Despite MacIntyre’s hostility, though, Kent continued to make prints, her concerns becoming more overtly political as the decade progressed.

“Kent produced the body of work that establishes her as a major, and uniquely significant, figure in the history of Pop Art”

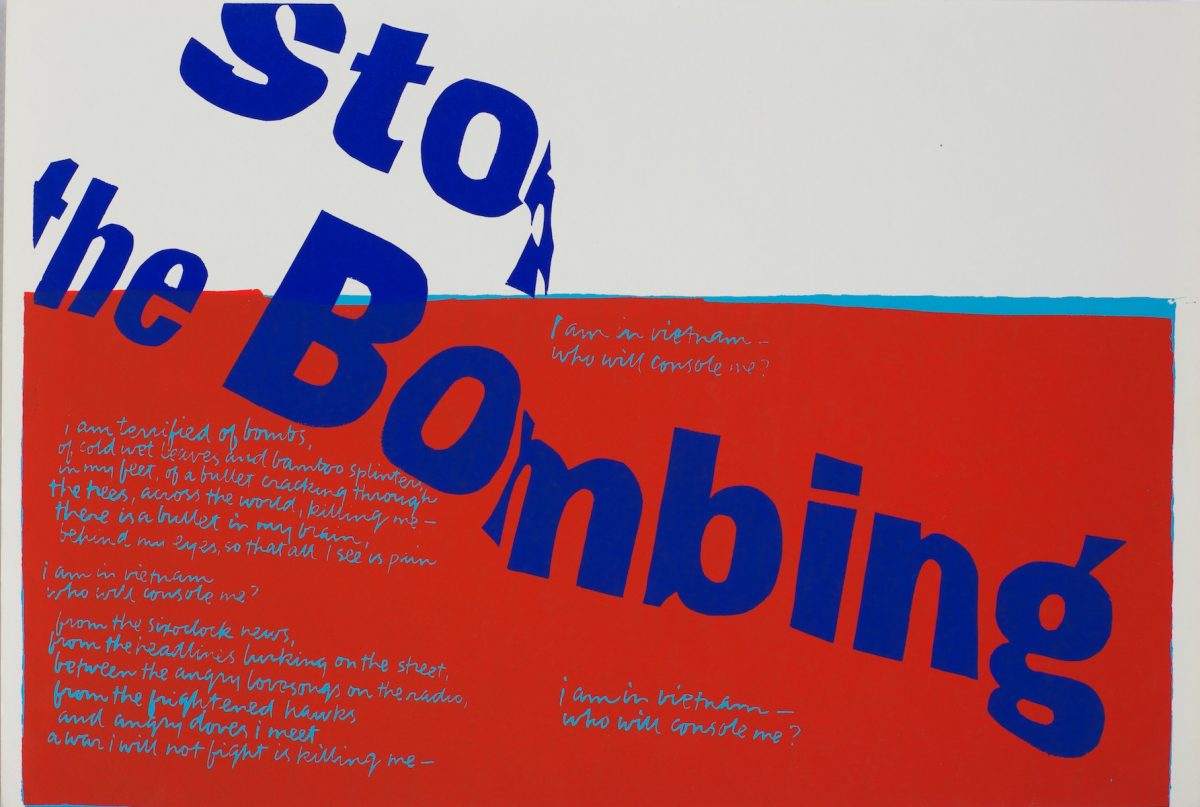

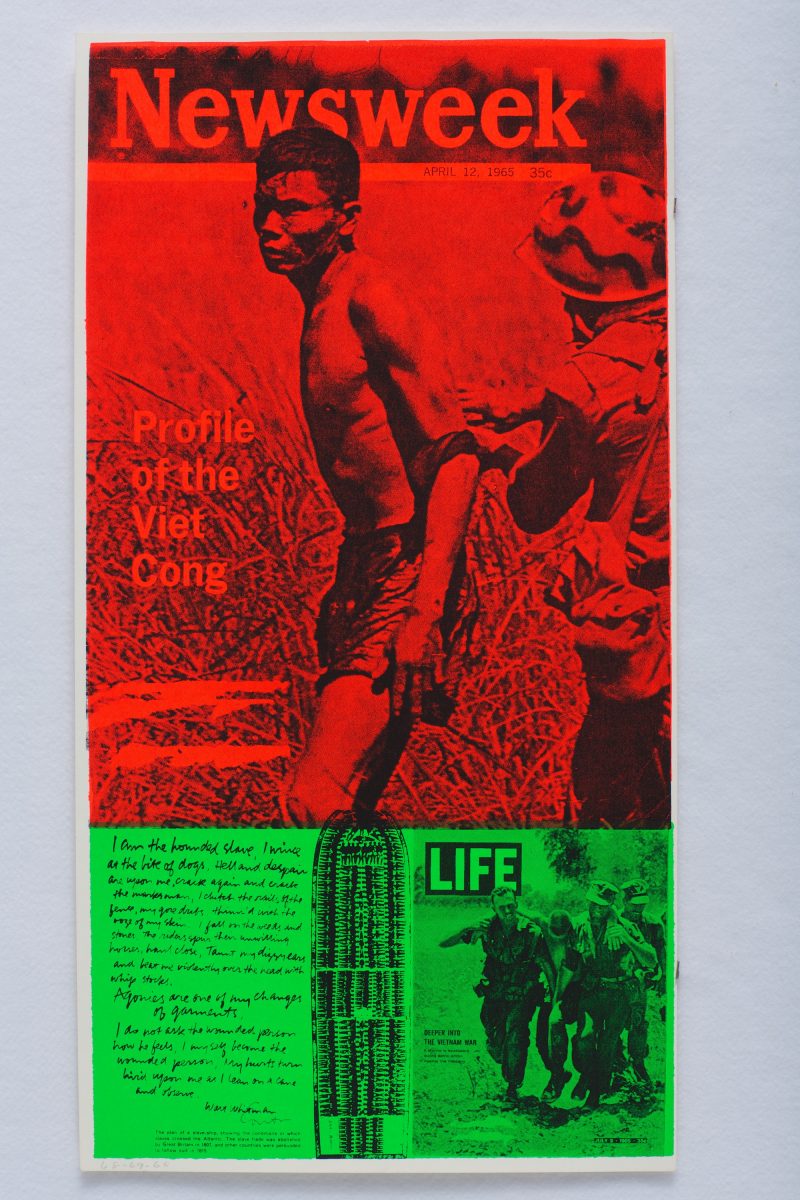

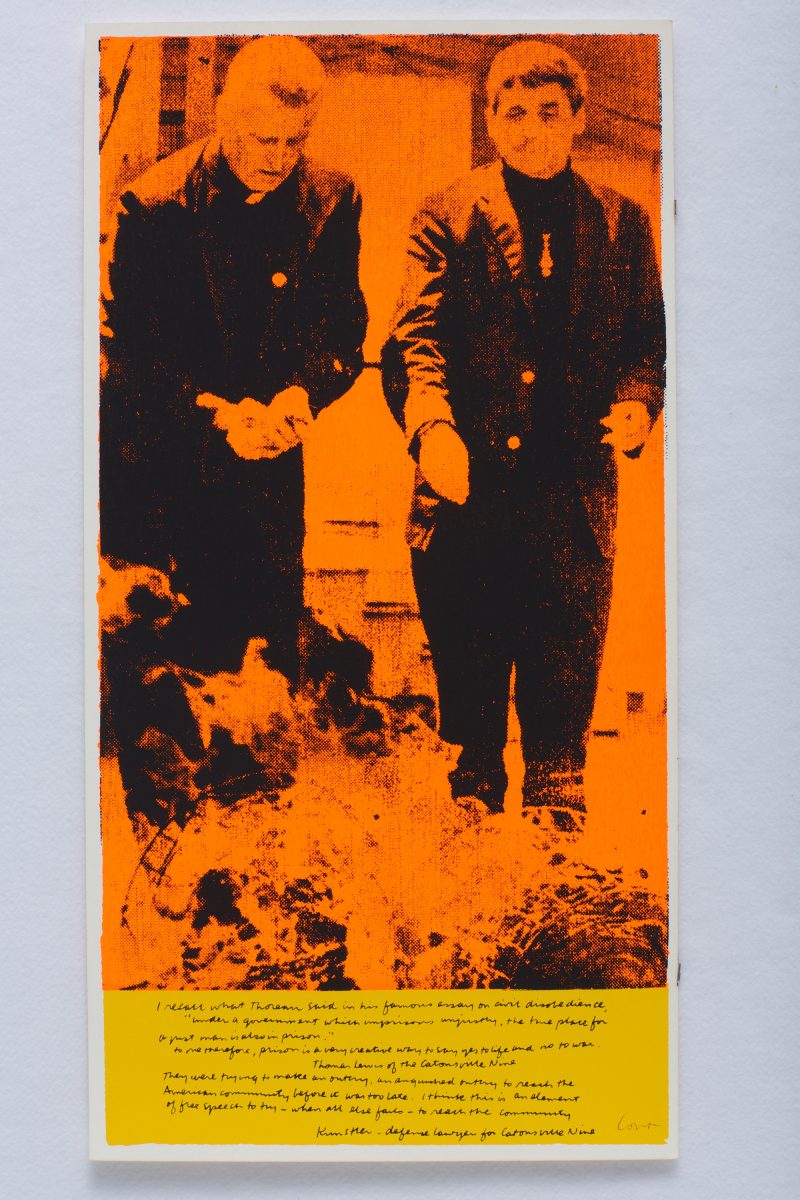

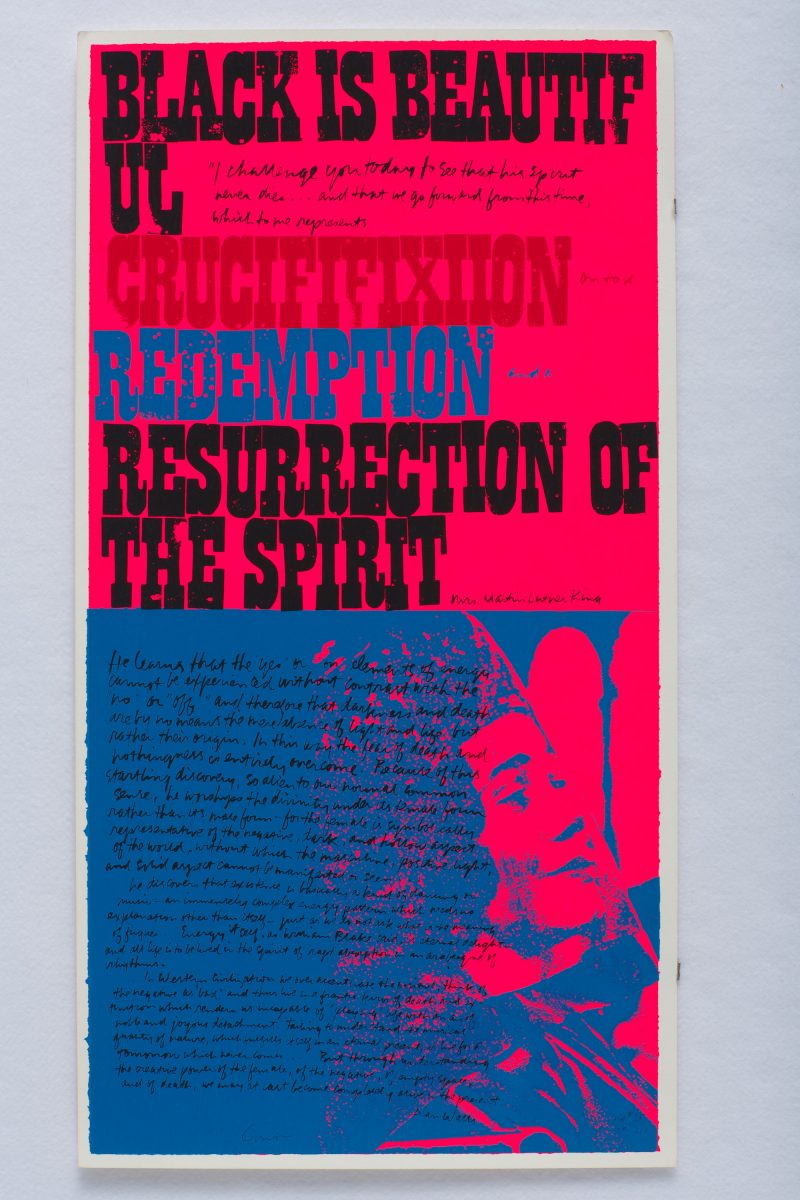

Her 1967 work Stop The Bombing was held aloft in protests against the Vietnam war, while News of the Week combined a Life magazine cover featuring American soldiers and a diagram of a slave ship with Walk Whitman’s words “I am a hounded slave”. There may have been echoes of her own predicament in that ‘hounded’. She left the Order in 1968 and moved to Boston, a couple of years before the Order and the College themselves broke with the Church. When she died in 1986 she left most of her estate to the community, which founded the Corita Art Centre 11 years later.

There had been artist nuns before Kent, including the 16th

-century Florentine Plautilla Nelli mentioned by Vasari in his Lives of the Artists, but the following half a millennium of predominantly male art history ignored them, along with many other women artists. It took the work of female commentators to acknowledge Kent’s foundational role in Pop Art with the publication of Come Alive! The Spirited Art of Sister Corita (2005) by artist and activist Julie Ault, and Dackerman’s meticulously researched Corita Kent and the Language of Pop (2015), in which she calls The Juiciest Tomato of Them All “an iconoclastic gesture that dismisses the long history of figurative depictions of the Virgin”.

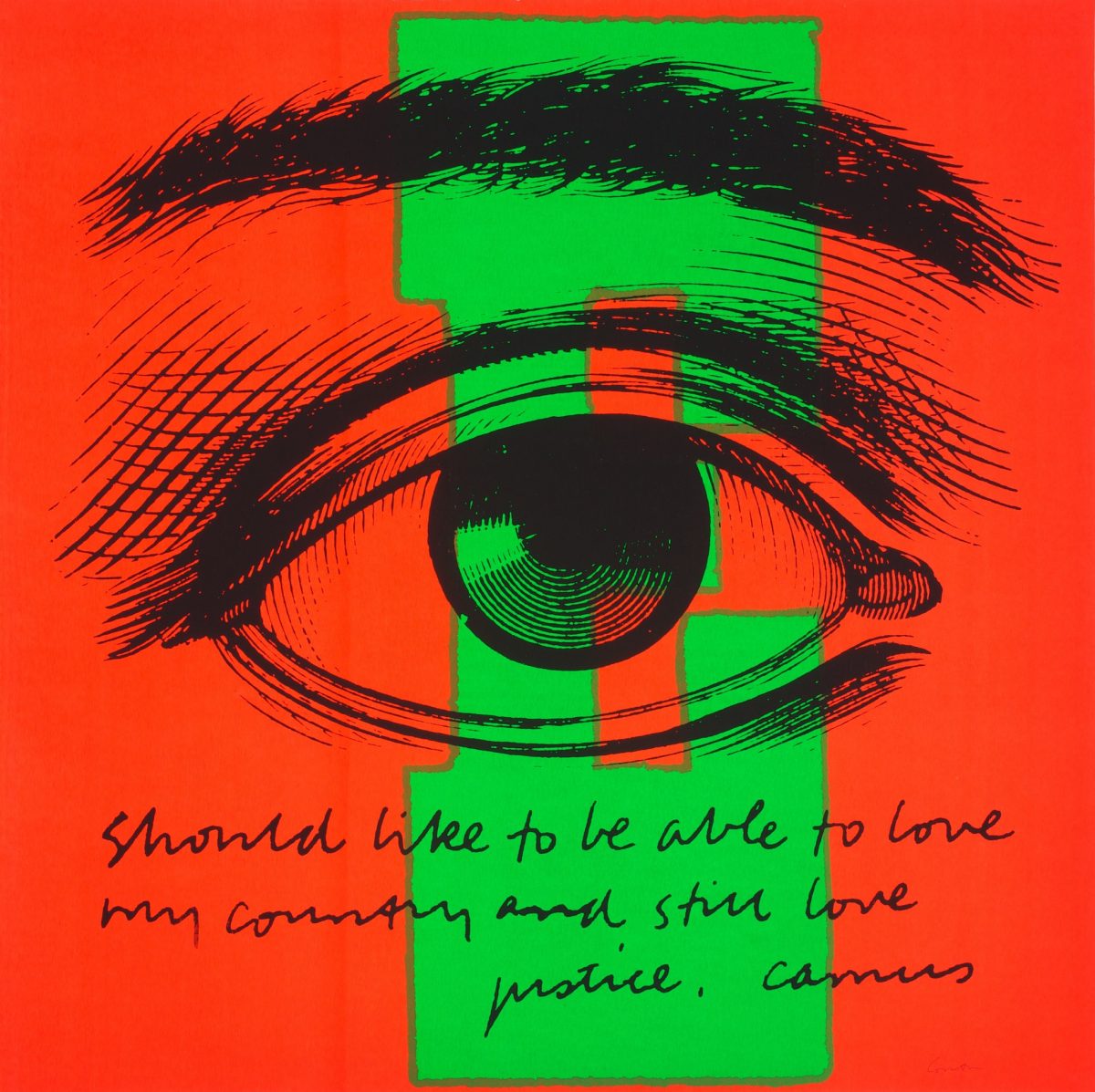

Warhol’s final body of work, the Last Supper paintings and prints, reprised religious figuration in the hope of transcending the depredations of the AIDS crisis. Kent’s art worked the other way around, deploying the vernacular visual language of her time to simultaneously liberate and reaffirm faith, a calm devotional voice speaking from within the maelstrom of consumer culture.

Steve Taylor writes about cities, music and urban culture. He recently started a PhD on underground music scenes and the future city