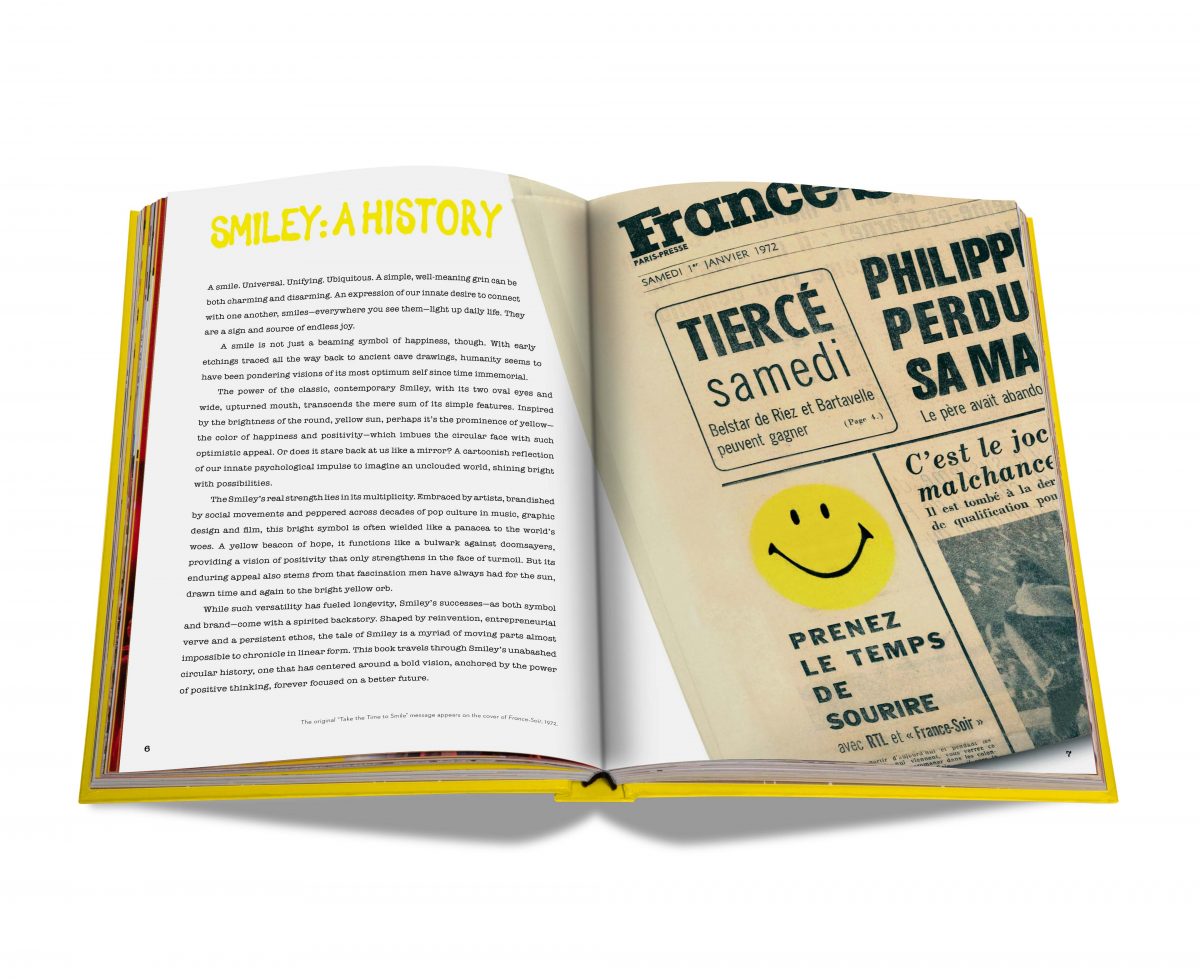

A circle, two dots and a curve. These three simple details make up one of the world’s most recognisable symbols: the smiley face. In its relatively short history (it was first trademarked in 1972 by Franklin Loufrani) it has been a mark of optimism, a commercialised logo, an iconic fashion statement, a sign of acid house rave culture, highly prized street art, and an emoji, reducing all verbal communication to a single pictogram. What started as a simple reminder to smile has been interpreted countless times over. In some cases, to infer the exact opposite.

The origins of the smiley is hotly contested. Loufrani is credited with its creation, thanks to its inclusion as an indicator of “good news” in the newspaper France Soir. However, artist Harvey Ross Ball also lays claim. He was commissioned by the Massachusetts-based State Mutual Life Assurance Company in 1963, to boost employee moral and “turn those frowns upside down”, with his own version of a smiling face.

“What started as a simple reminder to smile has been interpreted countless times over. In some cases, to infer the exact opposite”

Of course, the origins of this ubiquitous symbol of happiness stretch back much further. The remnants of a smiley can be found on a stone carving in a French cave, carbon dated to approximately 2,500 BC. Likewise, a 3,700 year old Hittite jug appears to be emblazoned with an optimistic expression. These are potentially the oldest smileys in the world, though archaeologists can’t be sure of their original intent.

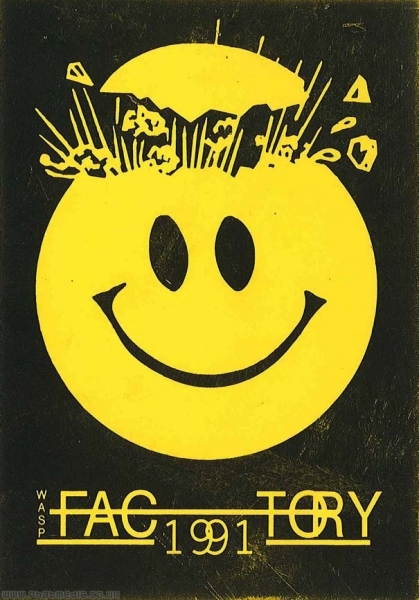

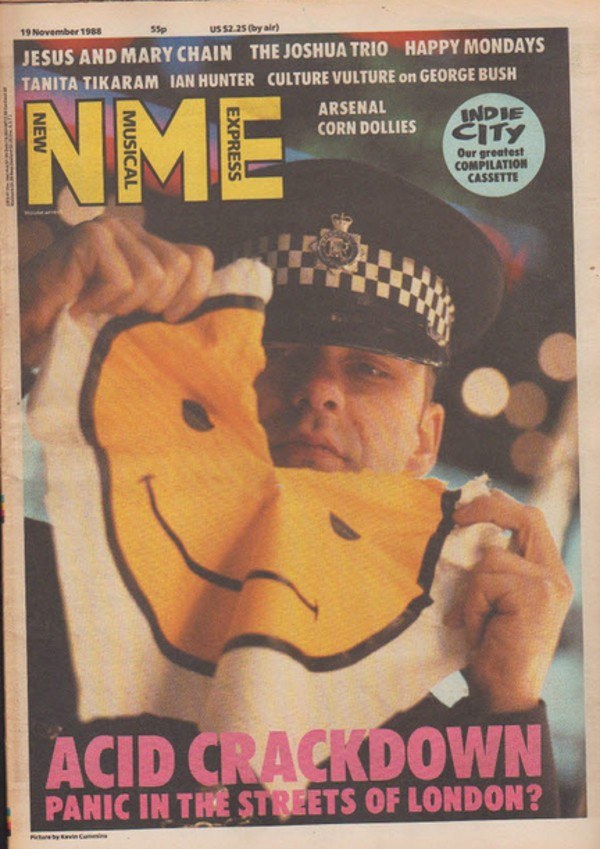

As the symbol accrued widespread recognition, its meaning began to change. What began as an innocent image of optimism matured into an emblem of anti-establishment counterculture. In the 1980s it became an ironic motif for the Acid House movement, kicking against regimes of conformity and austerity. It appeared on ecstasy pills, baggy T-shirts and underground poster designs. Dubbed the “second summer of love”, the movement was a hedonistic way for working-class people to reclaim space in Thatcherite Britain and the smiley became a subversive symbol for finding refuge from the pressures of daily life on the dance floor.

“The smiley became a subversive symbol for finding refuge from the pressures of daily life on the dance floor”

This association with illicit partying led to a loss of innocence for the one-dimensional smile, a vibe that was brought home through its appearances in other artforms. Alan Moore’s graphic novel Watchmen saw it appear splattered in blood on the original 1986 cover, as an ominous signifier of a dystopian world.

By the early 1990s, graphic artist Robert Fisher had re-appropriated the smiley for Nirvana. This wobbly version with crosses for eyes became synonymous with the grunge band’s punk rock attitude, yet it was also reclaimed as the ultimate ironic motif by Super Super magazine. The Indie Sleaze iteration featured dark, heavy eyes as if the happy character had been out on a 48-hour bender. The tension between optimistic symbol and disquieting irony is also seen in Banksy’s pieces Flying Copper (2003) and Grin Reaper (2005), which features menacing figures with knowing smiles stamped across their faces.

These varied contexts are a testament to the smiley’s widespread cultural impact. Reborn again as a universal means of communication, thanks to a widespread return to text-based systems, the friendly smiley emoji softens tone and promises that everything will be okay in emails, texts and on social media.

Despite continued reimaginings, it remains true to its original intent, recalibrating moods through an enduring, happy smile.

Jyni Ong is a freelance London-based writer and editor

Smiley: 50 Years of Good News is published by Assouline, out now