Photo by Ollie Hammick

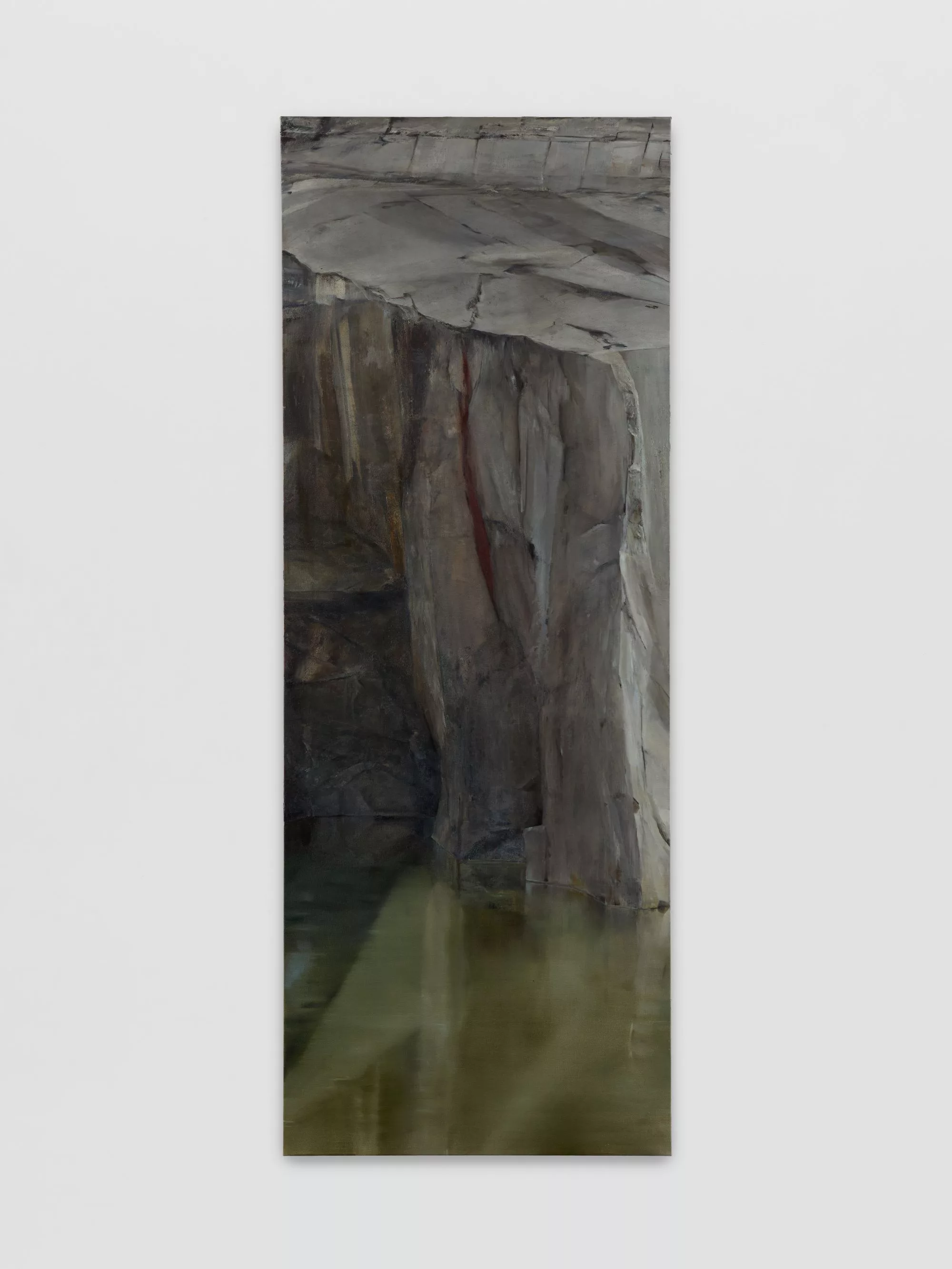

I’m not the biggest fan of thrillers. With the ominous soundtracks and the constantly underlying discomforting atmosphere, there’s something unpleasant about feeling as if something’s about to go wrong. We’re made to feel uncomfortable and uneasy with the lingering suspense. When one looks at Portuguese-Canadian artist Emanuel de Carvalho’s monumental paintings, we experience a similar bodily reaction. “It’s called anticipatory mental imagery,” de Carvalho explains to me. “When you perceive that something’s slightly off or if there’s something that doesn’t belong, your brain responds negatively, and you might even feel fear or angst.”

De Carvalho has always been intrigued by the human brain and vision. In 2013, he began his PhD in Medicine at the University of Amsterdam. “I studied medicine with the intent of specialising in neuroscience or neurology,” he tells me. “Though as I delved more into the world of academia, I became increasingly disillusioned by it. The output as a medic doing academic research can be quite niche as you publish for a select few.” In Amsterdam, he became part of an artists’ collective and participated in group exhibitions. “I was doing spoken word performances and I began experimenting with drawing as research output,” he shares. Medicine and humanities both play a part in De Carvalho’s way of perceiving and understanding the world, and we often forget that they’re more intertwined than we think. “Medicine and art aren’t entirely disjointed. It took me a while to reach a stage where my output didn’t include peer-reviewed academic articles anymore, but rather, became imbued in artistic creation that is much more accessible and universal.”

Photo by Ollie Hammick

De Carvalho completed his PhD in 2019 and continued in post-graduate studies in neuro-ophthalmology at University College London, while practising as a full-time artist. Throughout his practice, de Carvalho transfers his medical knowledge onto the canvas. “I was able to integrate some medical principles into the language of painting while also looking at other fields of thought that I thought were important, like philosophy,” he tells me. “Studying medicine really changed me as a person, in the sense that it heightened my awareness to the power of the body, the power of the brain.”

Photo by Ollie Hammick

In ground lack (2023), De Carvalho paints an empty lecture hall. From the perspective of the desk furthest away from the blackboard, de Carvalho allows us to see the whole hall in detail – a blackboard with faded writing in chalk, a semi-circle of slightly uneven desks, and one single book that’s open on one of the desks at the front. The setting is ominous and feels extremely silent. We feel like intruders in a space that isn’t ours, but, unlike a thriller where we ultimately find out why we might feel this way, de Carvalho leaves us to linger in this uneasy state. We remain standing in the empty lecture hall and are left wondering why our brain may perceive this space in such a discomforting and slightly threatening way.

Most of the places de Carvalho paints are familiar to us – waiting rooms, lecture halls, and cafes, to name a few. We’ve all probably spent some time waiting, discussing, and reflecting in these spaces. We’re engulfed and become part of these spaces through de Carvalho’s paintings, their monumental size taking us directly to those locations. “I’m interested in spaces where reflection happens or where there is a transfer of knowledge,” he explains. As we find ourselves in de Carvalho’s lecture halls or waiting rooms, we imagine ourselves quietly sitting and patiently waiting – we might be early or late to a lecture, or maybe we’re waiting for an appointment for ourselves or someone else at the hospital. “If you’re in a lecture hall or a waiting room of a hospital, there’s a code of conduct, a certain way you act because that’s just how you were taught.” In Discipline and Punish (1975), Michel Foucault writes how those imposing the norm and the correct moral codes of society are everywhere, dictating how one acts and, ultimately, leading oneself to become a moral subject of self-discipline.

Through de Carvalho’s paintings, we are led to reflect on our own self-imposed self-discipline while reminding us, at the same time, how these spaces can be subverted from their conventions. “I’m interested in spaces that have historically been places of resistance,” he adds. Think of French revolutionaries using cafes to meet or lecture halls where professors would meet students to discuss avant-garde thoughts and ideas, for instance. “It’s not all about detecting negative spaces; it’s also about potentially fostering a new way of behaving in that specific space.” As we find ourselves in the settings of de Carvalho’s paintings, we’re made to reflect on how we’ve historically used those spaces and reframe our way of thinking around them.

Photo by Ollie Hammick

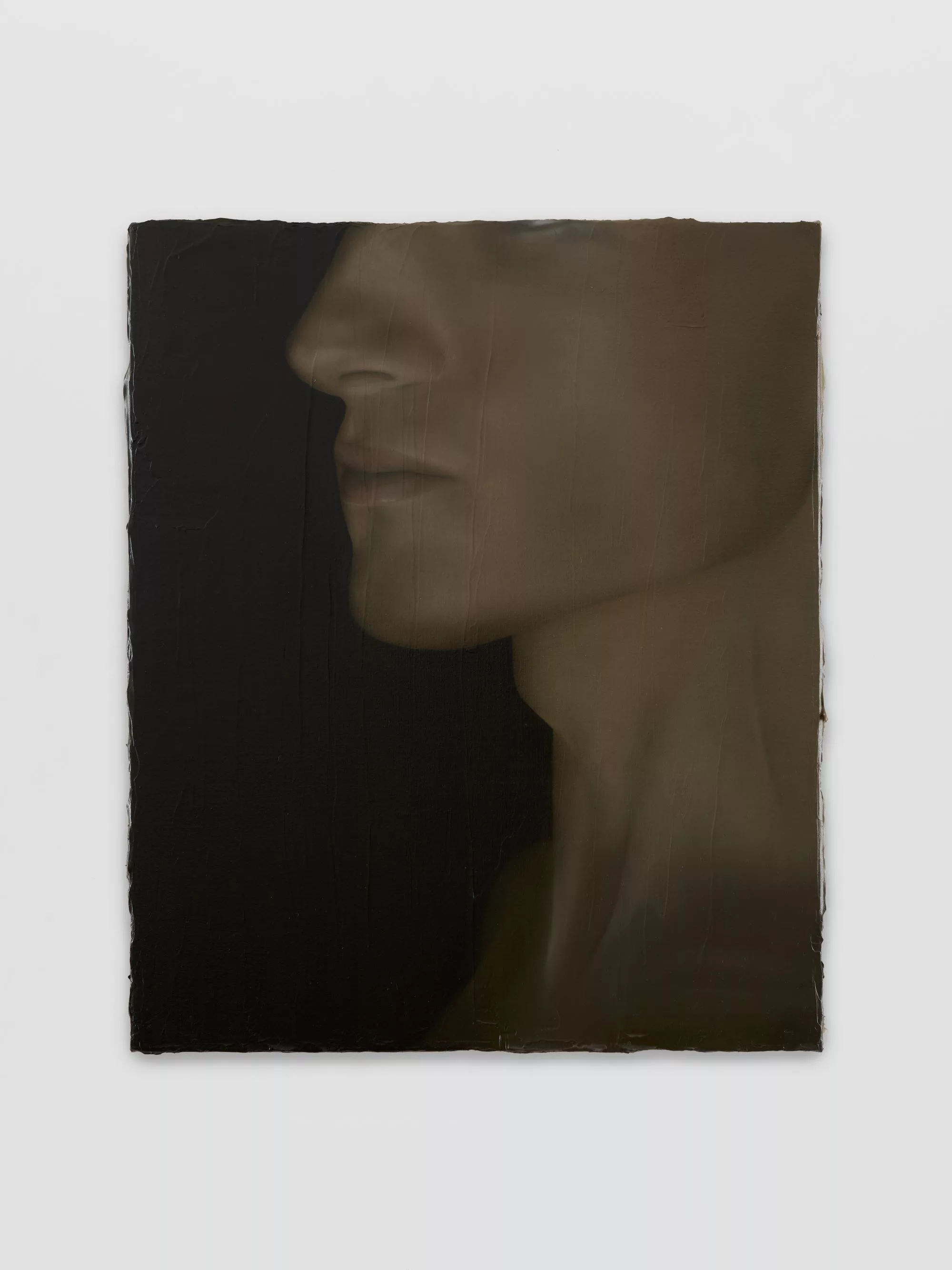

De Carvalho includes human figures in some of his works, though they act more as pieces supporting the central elements of the space. “When we see a painting with a person in it, we immediately look at the figure, we try to identify all the characters and traits that define that figure, and we try to place them within the context of the background,” de Carvalho tells me. “We’re very human-centric.” In code lack (2024), a man is absorbed by a decaying environment, with vegetation seeping through the cracks of the stone walls. He sits calmly and gently places his arm on a table, one of those recalling the rusty outdoor furniture of terraced European cafes. Yet, the background is undoubtedly the focus, engulfing us beyond the 3-metre canvas as the man provides scale to the massive space he finds himself reflecting in. “It’s a reflection of the unknown, of the inaccessible spaces within our human brains,” de Carvalho tells me of the dominating background in the painting.

In some others, the human figures take on a different role where they seem to be directly interacting with us. “The figures that you see are kind of militants,” de Carvalho says. In defence incessant (2023), two figures wearing sunglasses face us directly, protecting what lies inside the open doors behind them. “They’re saying, ‘We’re here. Acknowledge us. Do not deter us. We are here to stay.’” We’re no longer in the position of power, the comfortable role of the viewer looking at a painting in a gallery and unmasking all the secrets behind the painted passive subject. Rather, de Carvalho makes us equals. Many of his characters wear sunglasses or their faces are slightly cut off beyond the frame, like in neurotanz (2023). We’re unable to look at their eyes to gain a glimpse of their emotions – de Carvalho gives his figures the agency to decide what it is they want to reveal to us. Even with such a small intervention, de Carvalho leads us to rethink how we may interact with the figures in a painting. In Bodies of Work (1997), Kathy Acker writes about the power of guerrilla warfare and how even the use of the smallest interventions, such as language, can promote change. “In a way, each one of us is their own individual militant. We can provoke dialogue and change even just by offering an alternative view when you’re, say, having a discussion with a friend,” de Carvalho says. We enter an active relationship with his characters and are faced with the reality that we’re equals, forcing us to react in a visceral way as we’ll never know what to expect from them – we’re no longer in power even as we stand outside their enclosed frame.

Photo by Ollie Hammick

In his exhibition at Gathering London, de Carvalho will be showing two new sculptural installations. “They’re the first iteration of my collaboration with philosopher Catherine Malabou and neurologist Parashkev Nachev,” he explains as he shows me the renderings of the two sculptures – the first, lack skill I (2024), is a long and narrow object, reminiscent of a closed vitrine, while the second, lack slit system (2024), is a massive cube with a small open slit at the top. “The first sculpture will be directly informed by texts by Nachev and Malabou, while the second will be a vehicle for self-reflection while exerting a sense of authority with its monumentality.” Beyond the two-dimensional worlds of his paintings, de Carvalho’s sculptures will lead us to reflect on our brain’s way of perceiving our surroundings, as we interact with them, right here, in the ‘real’ three-dimensional world.

By engaging with de Carvalho’s works, we are able to detach ourselves from what we see and gain a third-point perspective into why we feel a certain way when we encounter certain stimuli. “With my practice, I want to raise awareness to the fact that we are neurobiological beings, that we have responses that elicit anxiety because our brains are undergoing a chemical process,” he says. He reminds us that ultimately, our neurological way of perceiving images and visual information is what plays into how we filter the world, shaping our moral and societal codes. As we become more hyperaware and reflect on why certain visual stimuli make us feel the way that we do, we might be able to start shifting our way of thinking. “If you’re faced with disruption and if you understand that the negative response resulting from it is a product of our brain, that’s when we can begin working on it.”

Written by Sara Quattrocchi Febles

Emanuel de Carvalho’s ‘code new state’ will be on view at Gathering London from 26th April to 1st June 2024. gathering.london

Emanuel de Carvalho’s ‘code new state’ will be on view at Gathering London from 26th April to 1st June 2024.

find out more