While this year’s Venice Biennale celebrates the event’s post-pandemic return, it also takes place against the backdrop of the war in Ukraine, casting a sombre note on otherwise celebratory proceedings. Although several projects reference the conflict, Kazakhstan’s debut pavilion at the 59th Biennale was disrupted by Europe’s newly unpredictable logistical landscape. An exhibition inspired by ideas of self-determination and imagination suddenly relied on these qualities in order to exist at all.

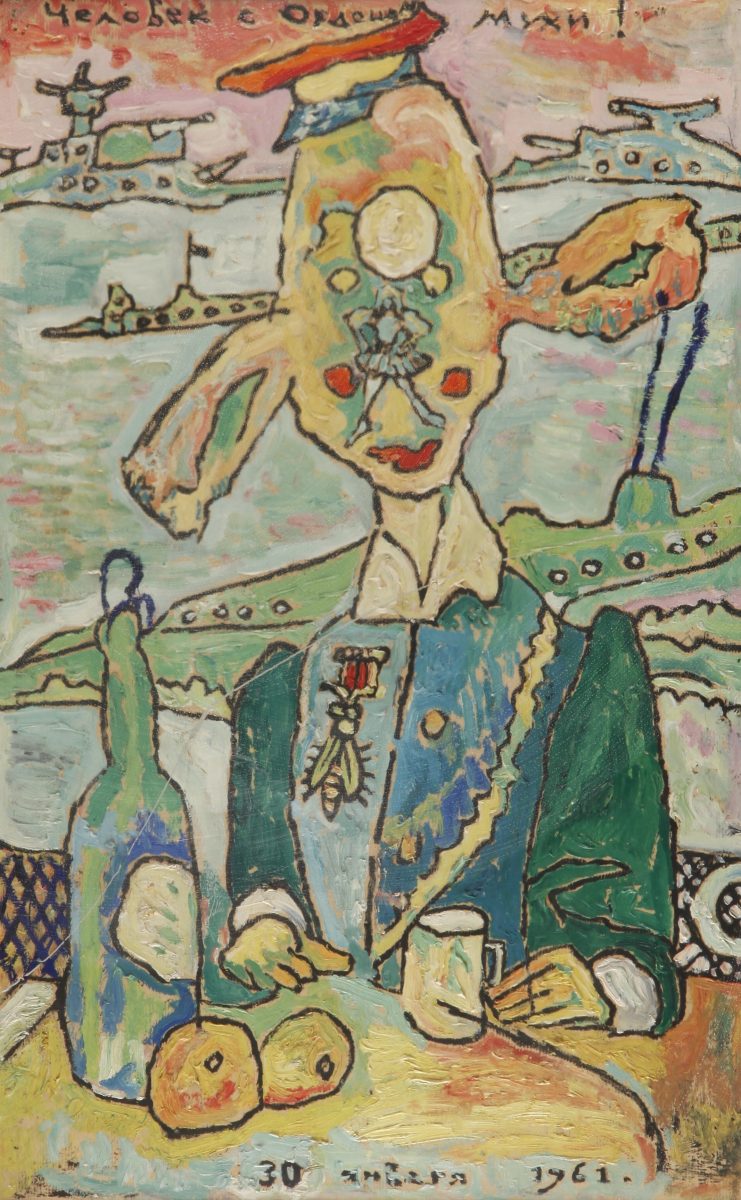

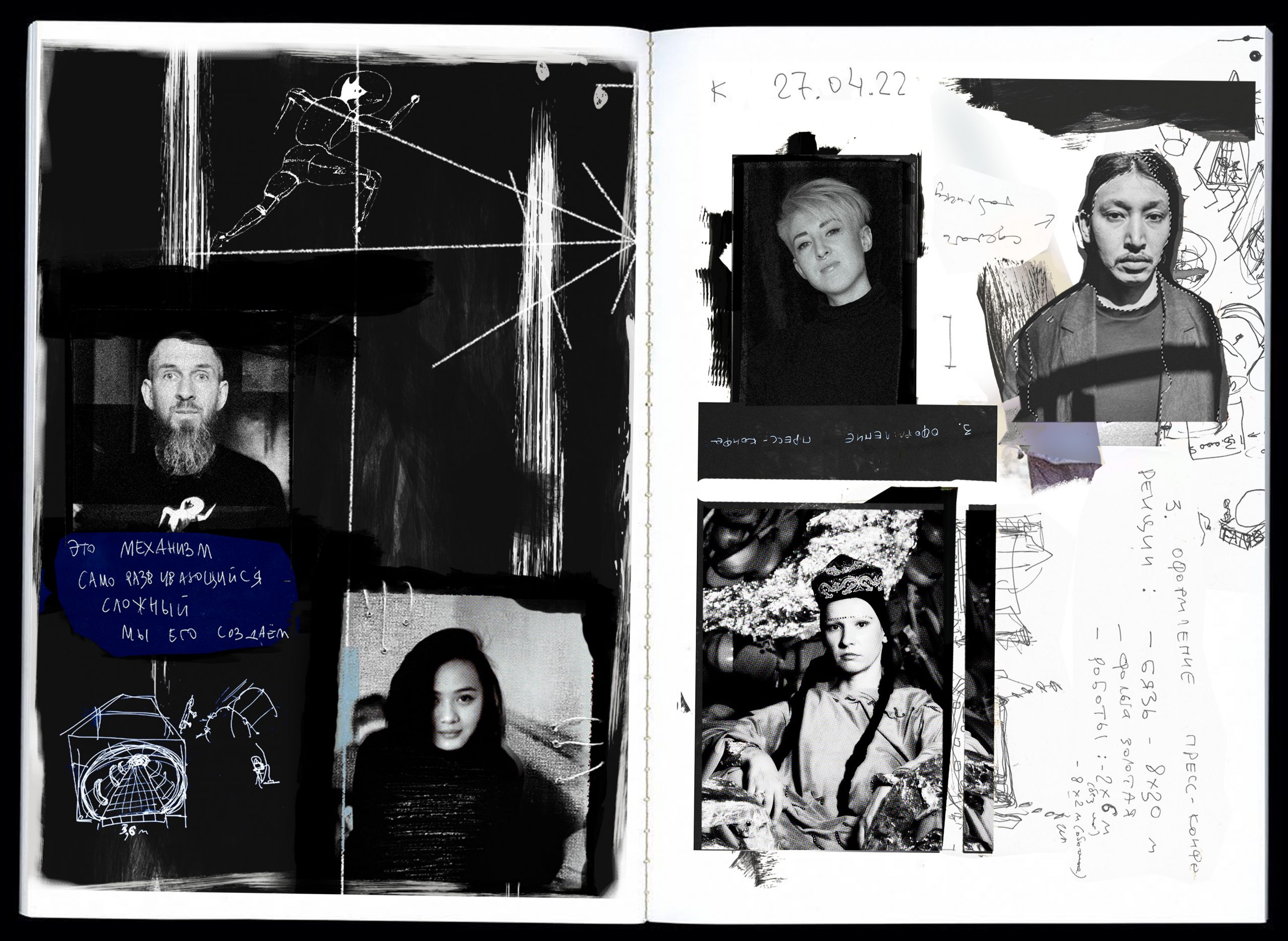

Transdisciplinary artist group the ORTA Collective, who work across theatre, visual arts, technology and research, are presenting LAI–PI–CHU–PLEE–LAPA Centre for the New Genius, an exhibition inspired by the life and works of Sergey Kalmykov, a Kazakhstani artist and inventor known for his eccentric lifestyle and prolific writings on culture.

The immersive Centre

was set to animate Kalmykov’s theories of the New Genius, an utopian philosophy which empowers all people to assert their genius, beyond everyday hierarchies of knowledge and societal position. The term is wrenched from its elitist origins, becoming a byword for self-actualisation and, ultimately, a new understanding of human value.

The ORTA Collective’s plans for the pavilion included five main areas, featuring 108 liquid-crystal displays, 3,000 programmable LED bulbs, a six-legged pneumatic refrigerator and an hydraulic washing machine. Visitors were to move through the space, guided by left-field and tech-oriented interpretations of Kalmykov’s teachings. Not content with completely redefining a key aspect of human epistemology, ORTA also sought to “create appropriate conditions for a controlled and sustainable opening of the Portal to the Fourth Dimension”.

“With just a few days to prepare, ORTA constructed makeshift installations from tin foil, extension leads and copious amounts of cardboard”

However, logistical delays in central Europe meant much of this went unrealised by the time that the Biennale opened in mid-April. Instead, with just a few days to prepare, ORTA constructed makeshift installations from tin foil, extension leads and copious amounts of cardboard. Fortunately, the project’s main performance, in which ORTA member Alexandra Morozova embroiders Kalmykov texts onto Soviet fabric tablets using ancient Kazakh techniques, was unaffected.

“Kalmykov wrote that he would remain in company with Picasso and Da Vinci,” says ORTA’s Rustem Begenov. “But he was a bum who died of starvation!” Despite the pavilion’s setbacks, there’s a glint in Begenov’s eye. He shares Kalmykov’s deeply held belief that his work will outlive him, that belief and faith will come long after the project’s end.

“Fifty-five years after his death, we’ve now brought him to the Venice Biennale,” Begenov continues. “That is symbolic.” Readings and interactive light installations give way to a group chant, where participants’ names are shown on a screen for everyone to declare them as ‘genius’. The rituals feel comforting against the makeshift backdrop: like a congregation gathered in a dilapidated church, but still lifted by song and worship. In a way, the situation is fitting: a barebones challenge sent to test the strength of ORTA’s Kalmykovian conviction amongst the riches and opulence of Venice.

Morozova began embroidering Kalmykov’s texts during the coronavirus lockdowns, describing the decision to do so as an impulsive but deeply felt process. The result is real-time inscription, a live translation of theory into practice, of thought into art. Among the audio equipment and cardboard sculptures, her work feels distinctly meditative.

New Genius is as much about critiquing today’s value systems as it is about restoring utopian thinking. Western ideas of individuality, master creators and the need for knowledge to be validated or passed down by institutions are all thrown into question by ORTA’s work. So too the idea of de-centring the Biennale’s geographical power axis, still evident as Western post-imperial powers dominate the main exhibition spaces.

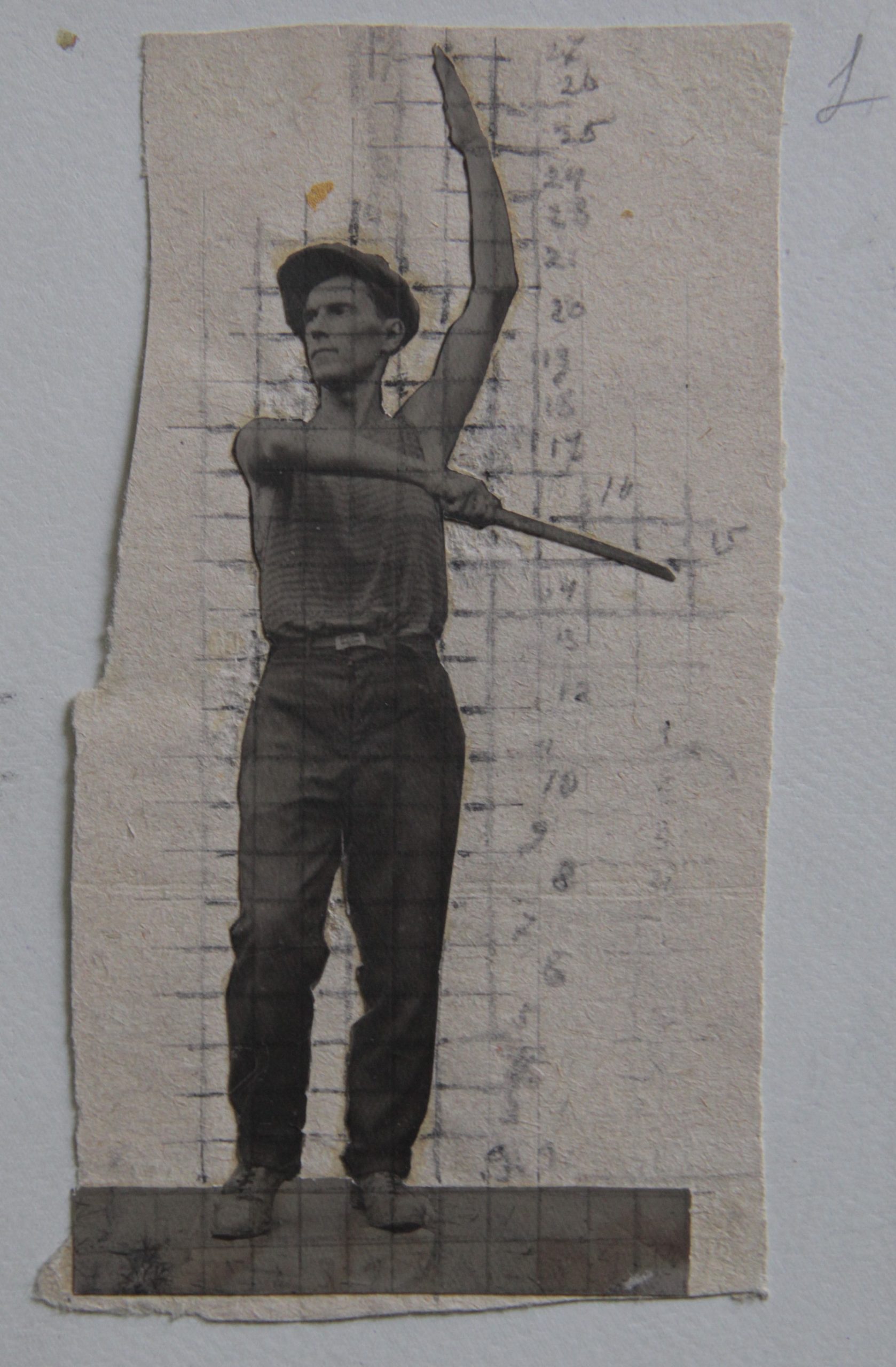

Sergey Kalmykov, collage and pencil on paper. State Archive of the Republic of Kazakhstan

“The result is real-time inscription, a live translation of theory into practice, of thought into art”

“We know what is expected from artists from countries like Kazakhstan: to show something a little bit exotic or strange,” Begenov says. “We are saying ‘no’. That art can be free. That if we’re from Kazakhstan, we can do something not connected to Kazakhstan if we want to.”

Audiences are encouraged to look within, to affirm their own genius before looking towards Kalmykov’s fourth dimension (ORTA plans to ‘open’ their planned Portal in November 2022, at the Biennale’s conclusion). “The old understanding of genius is that people are born naturally gifted,” Begenov says. “But what if genius is a kind of dimension that is present in every person? Why not nourish it?” Why not indeed?

Ravi Ghosh is Elephant’s editorial assistant