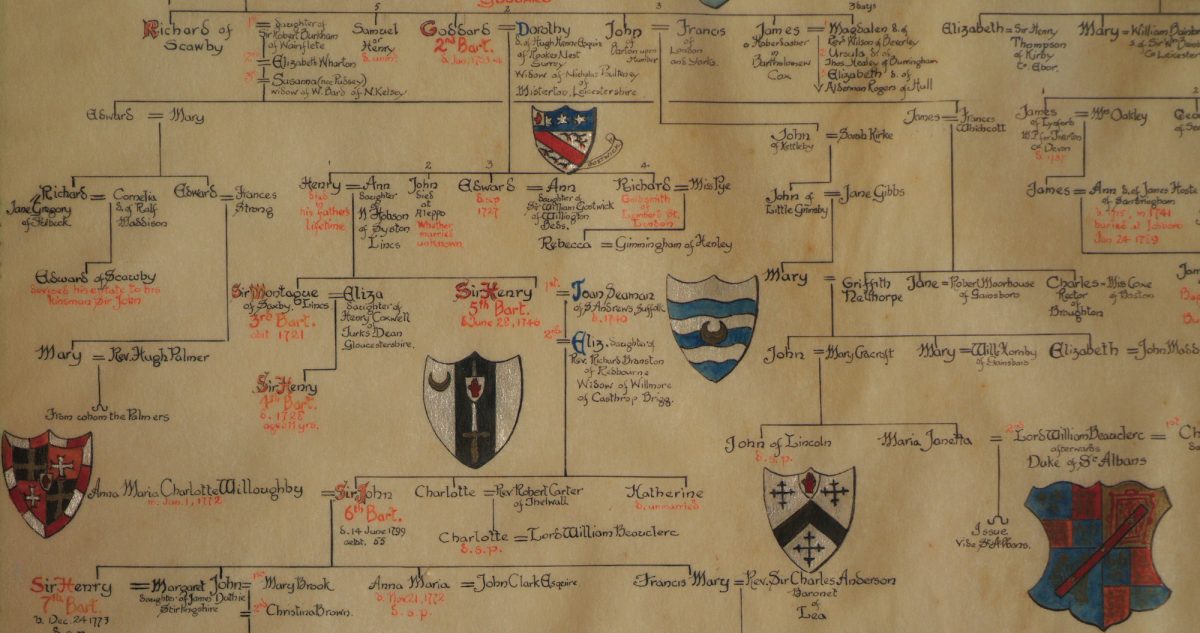

There’s a name for young adults who move away from their childhood home, then return: boomerangs. Generally, the end goal of most of the younger generation is to get back out there, but there is a small pocket of British society for whom staying at home is seen as a positive, not a negative: the aristocracy. For them, continuity within the ancestral family home is key to a way of life.

“It’s a kind of continuity that’s weirdly present in the tremendous conglomeration of animals, both live and represented, in their houses,” says Amie Siegel. “Family dogs, horses in stables, teddies, stuffed foxes, musical bunnies.”

It’s something that the American artist has noticed over the past three years, give or take, as she filmed in the country piles of the UK’s aristocracy. Her project? An intimate video that follows the movement of privately held paintings by the English artist George Stubbs from their stately lodgings to an exhibition at MK Gallery in Milton Keynes and back again. The idea came to Siegel when she was chatting with Paul Bonaventura, the show’s co-curator, who told her that many of the paintings were still owned by the families whose relatives (and livestock, mostly horses) they depicted.

“I found it remarkable, the idea that these works would come from a particular class that inhabits its own private, self-enclosed cultural world”

“I found it remarkable, the idea that these works would come from a particular class that inhabits its own private, self-enclosed cultural world,” she says. “And the opportunity to have that circumscribed world represented seemed to me very curious.”

Born in Chicago in 1974, Siegel has spent her career making meticulously researched video art that poses questions about systems of value, labour and ownership. Previous works have traced the source of marble from a dimly lit quarry in Vermont to a sparkling development in Manhattan, and the ritualistic dusting of Sigmund Freud’s personal collection of archaeological statues in the Freud Museum in London. One recent work, Asterisms (2021), explores “geological and social displacement on a planetary scale” through the lens of gold factories, oil recovery, desertification and horse training in the United Arab Emirates. Each segment unfolds on its own screen, the whole lot of them overlapping.

“There are things happening, but what is happening seems very much connected with the past even as it unfolds in the present”

This latest film, entitled Bloodlines, is more tightly focused. A single projection helps to hone our attention, as does the lack of a voiceover. All is calm, all is quiet. A uniformed girl in a white apron stokes a crackling fire, while other household staff lay tables, mop floors, trim hedges. Men and women in smart jackets and creamy breeches sip from silver hipflasks before a day’s hunting.

“There are things happening, but what is happening seems very much connected with the past even as it unfolds in the present,” says Siegel. The changing light and the ticking of clocks adds to the sense of time passing, if only abstractly. These are the “sedated homes of England” that Elvis Costello referred to in his 1986 song Little Palaces.

You don’t need to be a huge Stubbs fan to enjoy the show. Siegel isn’t. It’s more that the pair have shared interests. “Whether he was depicting their horses, dogs, animal menageries, shoots, fields or families, Stubbs was always pointing towards the social and aesthetic preoccupations of the landed gentry,” she says. “That was always interesting to me, and then there’s this idea that the paintings created to demonstrate their wealth and taste became objects of wealth and taste themselves.”

In 2013, Siegel recorded one of her films being sold at auction, then made that recording into a work of art in its own right. The film that was up for grabs, Provenance (2013), charts in reverse the global furniture trade from Chandigarh, starting in the homes of avid collectors and skipping backwards via auctions, previews, catalogues, restoration and shipping containers all the way to Indian ports. In her work she’s interested in the cultural migration of objects and what happens when something is lifted “like a great act of collage” up and out of its background.

“The paintings created to demonstrate their wealth and taste became objects of wealth and taste themselves”

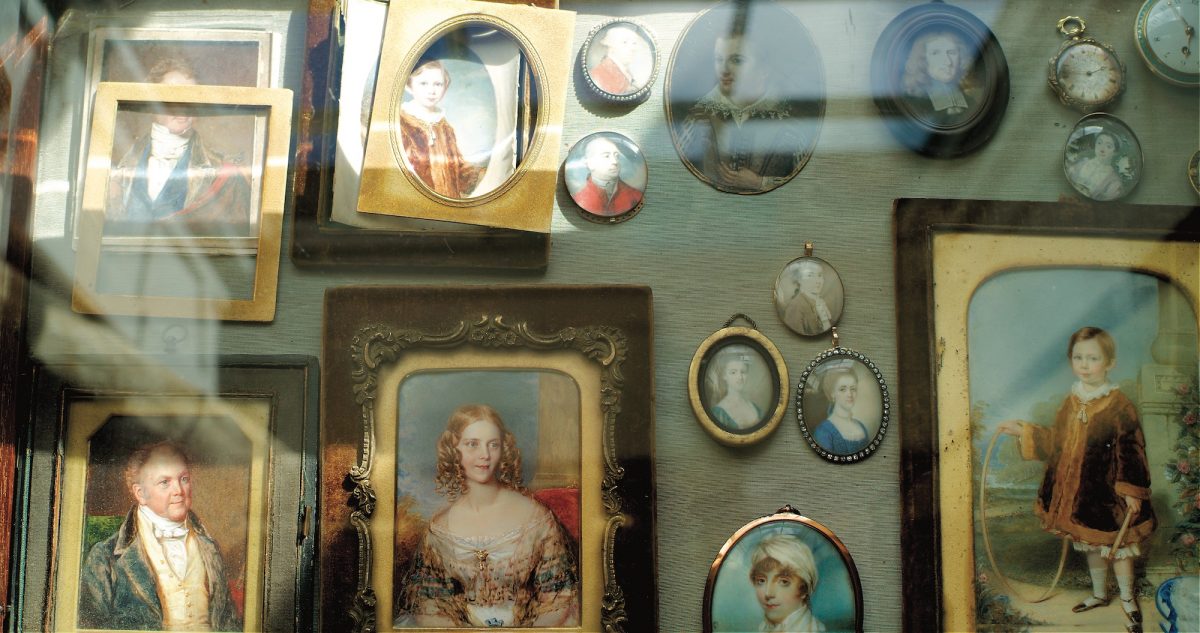

What does the change of context do to the gold-framed paintings in Bloodlines? In situ within their domestic interiors, they’re a part of a larger whole comprising crystal chandeliers, patterned crockery, and Victorian pinned butterflies. “There are layers and layers of representation and family and history collapsed together in one moment,” says Siegel. Installed in a contemporary gallery, each painting appears fresh and free from distraction. A work of art rather than a cultural artefact. A painting, not a picture. “It’s a part that speaks to a whole, but the whole is absent.”

Despite the socially charged title, which nods to familial, artistic, and equine genealogies, Siegel argues that Bloodlines isn’t intended as a critique. Like all her work, she says, “It asks questions.” Though it doesn’t answer them, there’s a lot that’s implicit. Close-ups of cobwebs and peeled-back wallpaper hint at the musty structures of ownership that shape British society. Shots of pieces of furniture shrouded in white sheets speak to the opacity that exists around seats of power and cultural objects. Even the wheeze of an old hobbling Labrador is ripe for interpretation.

- Amie Siegel, Bloodlines, 2021 (still) © Amie Siegel. Courtesy the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery

Siegel is reluctant to proffer an opinion. And yet: “I don’t ever do anything, a single cut or a single framing, or the inclusion or exclusion of an object, without intention,” she says. “What the viewer takes from that is completely subjective. But once you start to see a repetition of visual motifs, you’re in on it, right? It’s not a joke, but you’re in on the story.” A story of image-making and class conditions and cultural heritage.

“I don’t ever do anything, a single cut or a single framing, or the inclusion or exclusion of an object, without intention”

Together with Siegel, we move through the story, seeing and being seen by people and animals, real and depicted. She leads the way, peeling back the curtain of authority and revealing the surprising interchange between the world represented in the paintings and the world that still exists. “There were many times when we were filming when I felt like we were inside one of the paintings, which was uncanny,” she says.

What’s also uncanny is the return of the paintings to their homes, and the ease with which it happens. All is still calm, all is still quiet, as they’re rehung on the clunky chains that have borne their weight for centuries. There’s a feeling of eternity: “ownership in perpetuity,” Siegel calls it. “All it takes is for each painting to stop it’s slight vibration on the chain, and then it’s as if it never left,” she says. Like a boomerang, back again.

Chloë Ashby is an author and arts journalist. Her first novel, Wet Paint, was published in April 2022

Amie Siegel: Bloodlines is at Thomas Dane Gallery in London until 23 July 2022