When Stefanie Moshammer was 12 years old, she sat with two friends in one of their bedrooms and told them her mother was an alcoholic. “For a long time I wasn’t able to say it to anyone, and no one knew what was going on at home because I was so embarrassed,” she recalls. She felt that familiar flush of shame, but a wave of relief washed over her too. Her friends’ reactions, however, brought her back to earth.

“They were more wordless than emotionally supportive,” the Austrian artist says. She couldn’t blame them, they hadn’t had to grow up as quickly as her after all, but she learned a hard lesson about the social awkwardness of addiction that day. As she headed home, the silence that had sprouted between them swelled into something bigger, and it would go on to manifest as an emotional wall she’d have up for many years to come.

Now in her 30s, Moshammer has long since confronted the discomfort wrapped up in her reality, and is finding new ways to speak about the texture and terms of life with addiction through her art. “Once I decided to address the topic in my work, there was no reason to feel ashamed anymore,” she says. “I can’t change my family’s history, and I can’t change my makeup. Neither can my mother. It has made us the people we are today.”

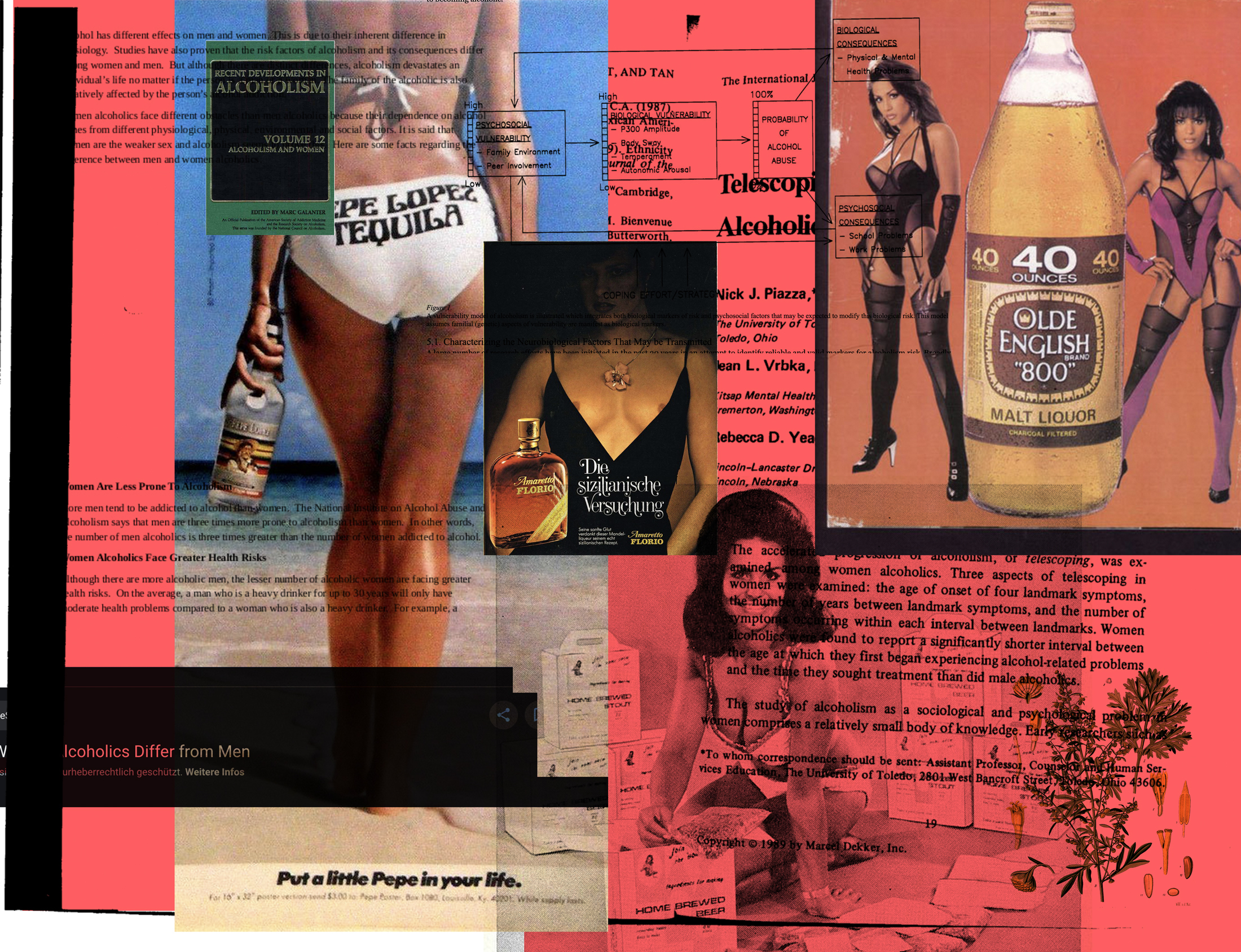

In Moshammer’s ongoing project Each Poison, A Pillow, the artist brings assembles films, photographs and installations that explore both her relationship with her mother, and the subject of female alcoholism more broadly. Alongside personal works created in collaboration with her mother, the project also includes an array of found material, old magazine clippings and social-media screenshots.

“Besides experiencing it myself, I tried to go one step back and look at the topic of alcoholism from a research perspective,” she explains. “This includes scientific and medical analysis, looking into the production of alcohol, the usage of alcohol in medicine and rituals, cultural patterns of women drinking, the representation of women and alcohol in commercials, art or religion.”

Certain works within Each Poison, A Pillow act like pivotal hinges for the narrative, guiding us through the artist’s emotional odyssey. In one installation, a mix of medical images related to research around addiction, and archival images from the artist’s family albums, are printed on pillows and scattered in a pile. “The pillows work as a reference to the domestic space in which most alcoholism among women happens, and as a symbol for the way people look to drink for comfort; like something to lean on and make them feel good,” Moshammer says.

“My mother is not a bad mother. She is sweet, kind, generous and one of the strongest women I know, just as she is one of the most vulnerable”

Elsewhere, a 16-channel video installation comprises looping clips of both Moshammer and her mother’s eyes. “It bears witness to the deep but fragile affection that binds mother and daughter: they face each other, eye to eye, through interposed screens,” she says. “Each look expresses a different emotion, where I, as the daughter, am trying to adapt my mother’s expression simultaneously.” By attempting to mirror her mother’s countenance, the artist is playing with the nature of empathy, and putting herself in her mother’s shoes.

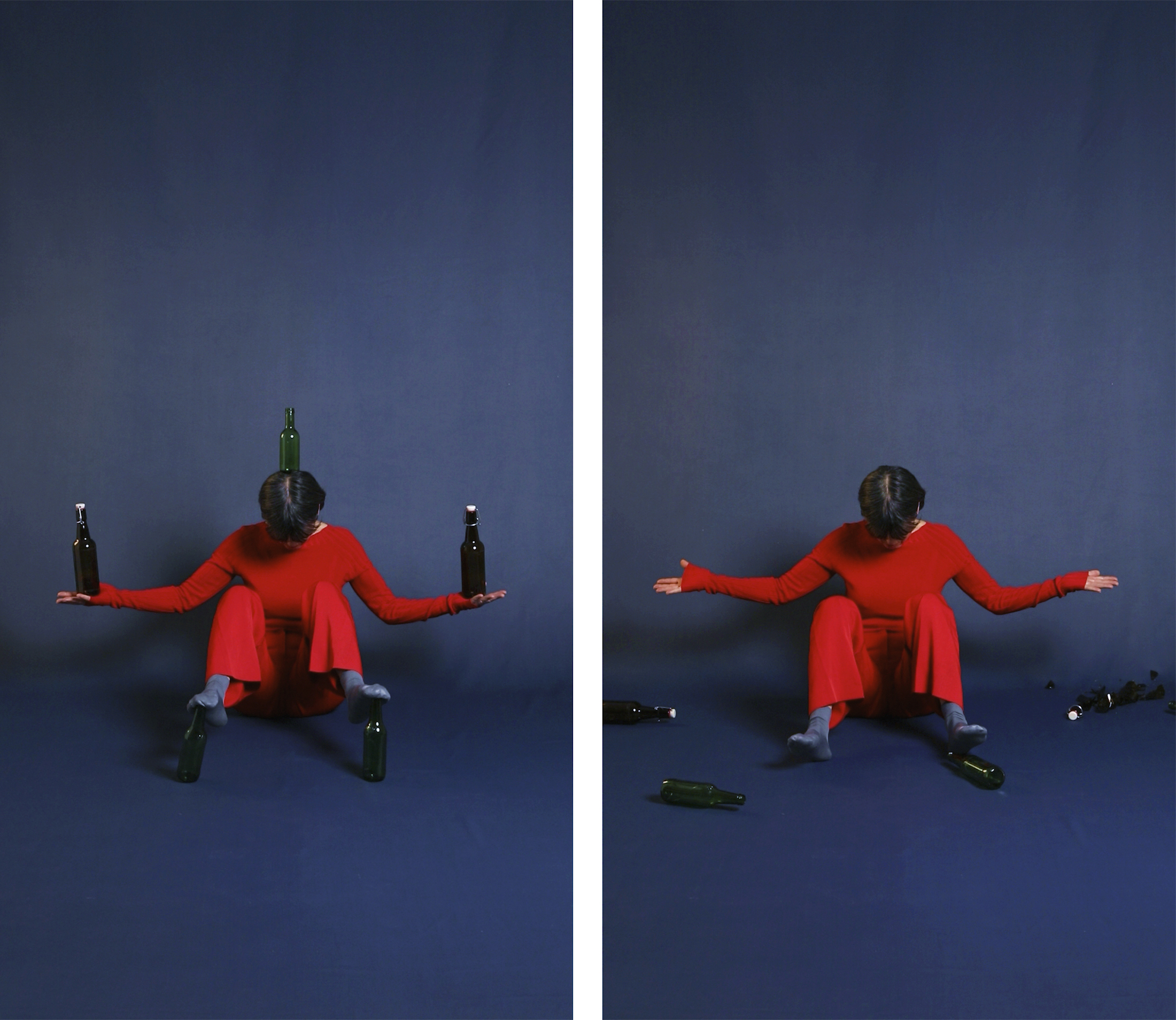

Then there are a series of videos in which Moshammer’s mother balances bottles upon her body. “It’s a collaborative work in which I am trying to understand her struggle with alcoholism and its effects on me as a daughter,” she explains. “These positions show the strength she has to resist, until it gets to the point she cannot. It explores that constant struggle between holding it together and falling apart.” The recorded noise of falling bottles is wince-inducing despite its inevitability.

“It’s a collaborative work in which I am trying to understand her struggle with alcoholism and its effects on me as a daughter”

Addiction is a process. In the Alcoholics Anonymous programme, they teach that you are never ‘done’ with alcoholism, only ever in a state of recovery. It makes sense that Moshammer’s artistic response should forever be evolving in new directions too. “The work exists as fragments, rather than one single narrative line,” she says. “There is no beginning and no end. It’s an up and down, forwards and backwards process full of puzzles that might never fully fit together, and that’s okay.” There is no neat answer in it, she adds, describing it as like holding a prism up to the light and looking at it from multiple perspectives to reveal new truths.

Each Poison, A Pillow opens up a conversation about how we can use art to feel around the edges of some of our most personal and painful experiences, while also considering the ethics of how to take care of telling someone else’s story alongside your own. Moshammer says it will always be a learning curve, and impossible without the understanding and collaboration of her mother. Together, they can control the narrative, deciding between them how they want it to be told.

“Once I decided to address the topic in my work, there was no reason to feel ashamed anymore”

Beyond this, the most important goal for the project is to bring attention to the topic of alcoholism among women at a societal level. Alcohol consumption is rigorously normalised, in particular for women, Moshammer says: it is often represented as a self-medication for pre-existing mental health issues, as a way to cope, loosen up or let go. “This is in direct contrast to male alcoholism, where alcoholism is seen as a primary illness that causes mental health issues,” Moshammer explains. She wants this work to inspire us to consider where the deep human need to be intoxicated really comes from.

Stage Two, 2022

In a text accompanying the project, Moshammer writes, “My mother is not a bad mother. She is a sweet human, kind, generous and one of the strongest women I know, just as she is one of the most vulnerable.” They are affecting words because they demonstrate how the children of alcoholics often defend their parents, trying to explain that alcoholism is an illness, all the while knowing this is still a hard thing for people to accept, especially when an alcoholic’s behaviour can be so destructive to others. “I’ve always wanted to protect my mother’s image,” Moshammer says.

Images that reveal the science behind addiction mix with artworks that unfold the human heart to give form to difficult feelings through videos and pictures, textiles and words. Together with Moshammer we travel the uneasy tracks between illness and recovery, and between stigma and shame.

is a writer and editor based in Brighton, UK. She is the daughter of an alcoholic

Stefanie Moshammer’s work can be found on her website