After winning the prestigious Helvetia Art Prize at Liste in Basel last June, the Swiss painter Andriu Deplazes lay low for a few months, painting the walls of his girlfriend’s flat rather than canvases, having graduated from art school just one year before. Yet 2018 sees his first institutional solo show (at the Aargauer Kunsthaus in Switzerland until 14 April) and his first solo show in London, at a new project space in Dalston: Lungley Gallery. His work has been compared to various 20th-century painters, yet it is when he speaks of the motifs of art deco or medieval art from the chapels of eastern France that he is most enthused. I visited him at his Brussels studio just a few days before the opening of his first show of the year.

After winning the prestigious Helvetia Art Prize at Liste in Basel last June, the Swiss painter Andriu Deplazes lay low for a few months, painting the walls of his girlfriend’s flat rather than canvases, having graduated from art school just one year before. Yet 2018 sees his first institutional solo show (at the Aargauer Kunsthaus in Switzerland until 14 April) and his first solo show in London, at a new project space in Dalston: Lungley Gallery. His work has been compared to various 20th-century painters, yet it is when he speaks of the motifs of art deco or medieval art from the chapels of eastern France that he is most enthused. I visited him at his Brussels studio just a few days before the opening of his first show of the year.

What is Brussels like for you as an artist?

Brussels is small but it remains really international. I like walking around the city. I like the North African presence, the diversity and cultural scope that exists. I like the space that one has for creativity here. And I don’t just mean artists being creative, I mean that there is a degree of creativity to life in the way that people improvise, they are building and constructing and fixing things all the time. There isn’t a systematic way of organizing things; where I’m from in Zurich, everything is just “as it should be”, whereas here things are left to become run down, just as people find alternate means of getting by.

How has your practice evolved since you had your first solo show last summer?

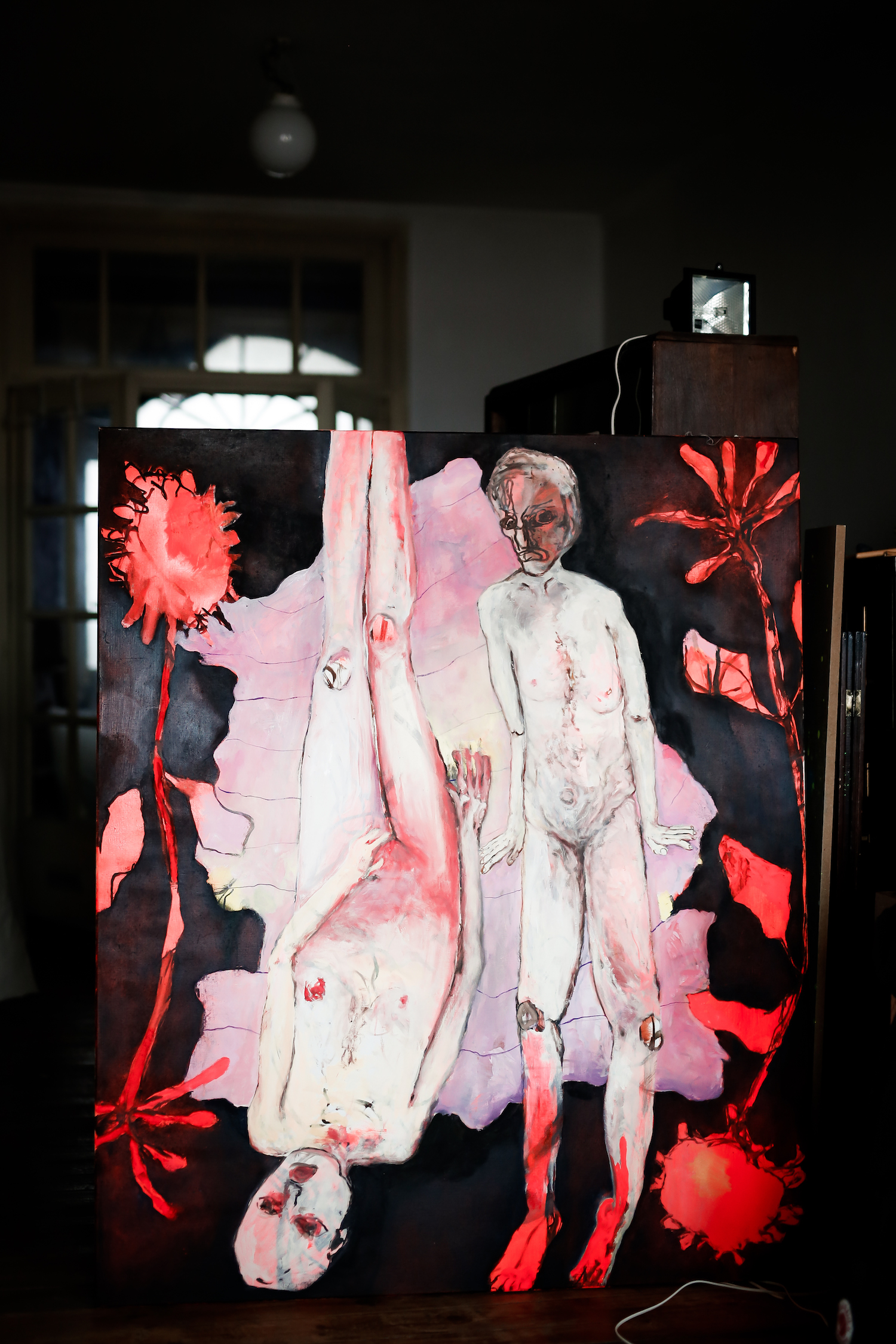

I took a bit of time off, but then I was offered my first museum show and I had just five months to get everything together. I started with a lot of drawings—there are over 100 sketches—and from these I started to develop a few ideas. I was really inspired by one hiking trip I took in Switzerland last year, during which I visited several mountain chapels with paintings and sculptures of Jesus from the middle ages, depicting him in this really rigid pose; I was very inspired by their deformation and its abstraction of the bodies. I took this idea and pushed as far as I could.

What themes do you feel most close to in your work?

People say that my work is apocalyptic, but I think that is just because catastrophism is very much something that defines our current moment. I’m not looking to respond to any kind of atmosphere of social malaise, in fact, these desolate landscapes and their acid colours respond far more to my desire to create an artificial landscape. I am interested in the visual language of animations and artificial architecture such as the technology used to create prototypes and models. I incorporate that with a need to also create something that touches what is inherently human about us; that is where the repeated motif of nature comes in. I’m interested in the way we use it and the way that we behave in it. Sport, just like nature, has become something of a modern religion; people force themselves to go jogging like they force themselves to go to mass. We engage in this self-flagellation to feel something I think—we no longer feel like we’re in our bodies. These themes branch out into larger subjects such as romance, personal sexuality, prudery, the sensation of being observed, how it feels to be in our bodies, what it means to be naked. I like playing with feelings that can’t be explained.

Why do you paint? There seems to be the general consensus that it’s a medium that has become popular again among young artists.

It is a question that I’m often asked, but I don’t really understand why. You wouldn’t ask if classical music was back? Painting has a very profound tradition and history and it is something to which I’m very attracted; I think it’s really important that it exists. I was initially drawn to painting without necessarily understanding why. It was only once my practice developed that I began to understand the history behind it. It is also something which incorporates artisanal skill, as well as conceptual and philosophical practices. I always enjoyed artisanal activities, and so for me, now living in the city, painting allows me to use my hands, to experiment and try out different things.

Can you explain your creative process a little?

I like learning on my own, experimenting with techniques, aiming for an individual visual language. Most of these works start out with brightly coloured backgrounds, over which I add darker layers. Sometimes I know exactly how I will develop a piece, based on sketches and pre-studies, other times the paintings will emerge over the course of its creation.

What is your favourite painting?

I love paintings from the middle ages, in particular, Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece in Colmar. It is a painting from the beginning of the 16th century and Grünewald spent years working on it. There is a crazy abstraction to it; Jesus is depicted with giant feet, completely green as if they were rotting like a piece of ageing meat. I think it’s fascinating.

Can you tell me about the androgyny of the figures in your paintings?

Androgyny is becoming fashionable and I think it is becoming more and more acceptable for men to open up to their femininity. I grew up in a feminist environment—that’s not to say that feminism is a central topic of my work, but these are nevertheless issues that have influenced me; it doesn’t have to be a political statement for there to be a visual investigation of such subjects. The nudes that I paint do not focus on a gendered physicality. I don’t think it is important that the viewer identifies the bodies as either masculine or feminine but that they feel that there is something human about these figures, this might show through a certain look or gesture or behaviour, and this is what is really universal.

Photography © Estelle Parewyck