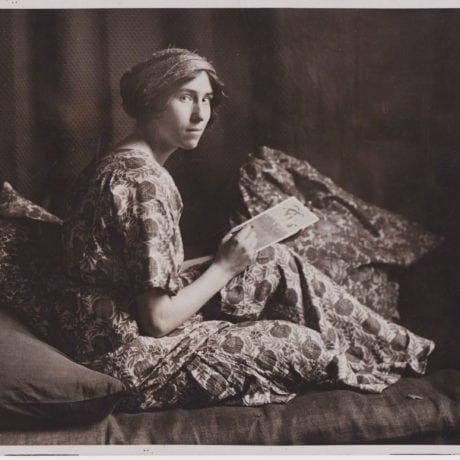

Rhythm & Colour is the inaugural title from Golden Hare; a new publishing house established this year by Mark Jones, the former director of the V&A Museum. Written and researched by Richard Emerson, the detailed monograph examines the intertwined lives of three artists and dancers of the twentieth-century avant-garde, Hélène Vanel, Loïs Hutton and Margaret Morris, and their influential relationship on the dance and performance scene in Europe, alongside modern art histories.

When she was just twenty-two years old, the dance artist Margaret Morris opened a private members’ club for artistic and literary circles (members included Katherine Mansfield, Ezra Pound and Charles Rennie Mackintosh). She also started a theatre school for adults and children—named the Margaret Morris Club—on the King’s Road in London, which led to summer schools in Wales, Devon and the South of France. It was here that she met Loïs Hutton in 1918, who became her second-in-command and principal dancer. Hélène Vanel would join later as a student in 1921. Two years later, all three women were involved in hosting the Margaret Morris Summer School in Antibes on the French Riviera.

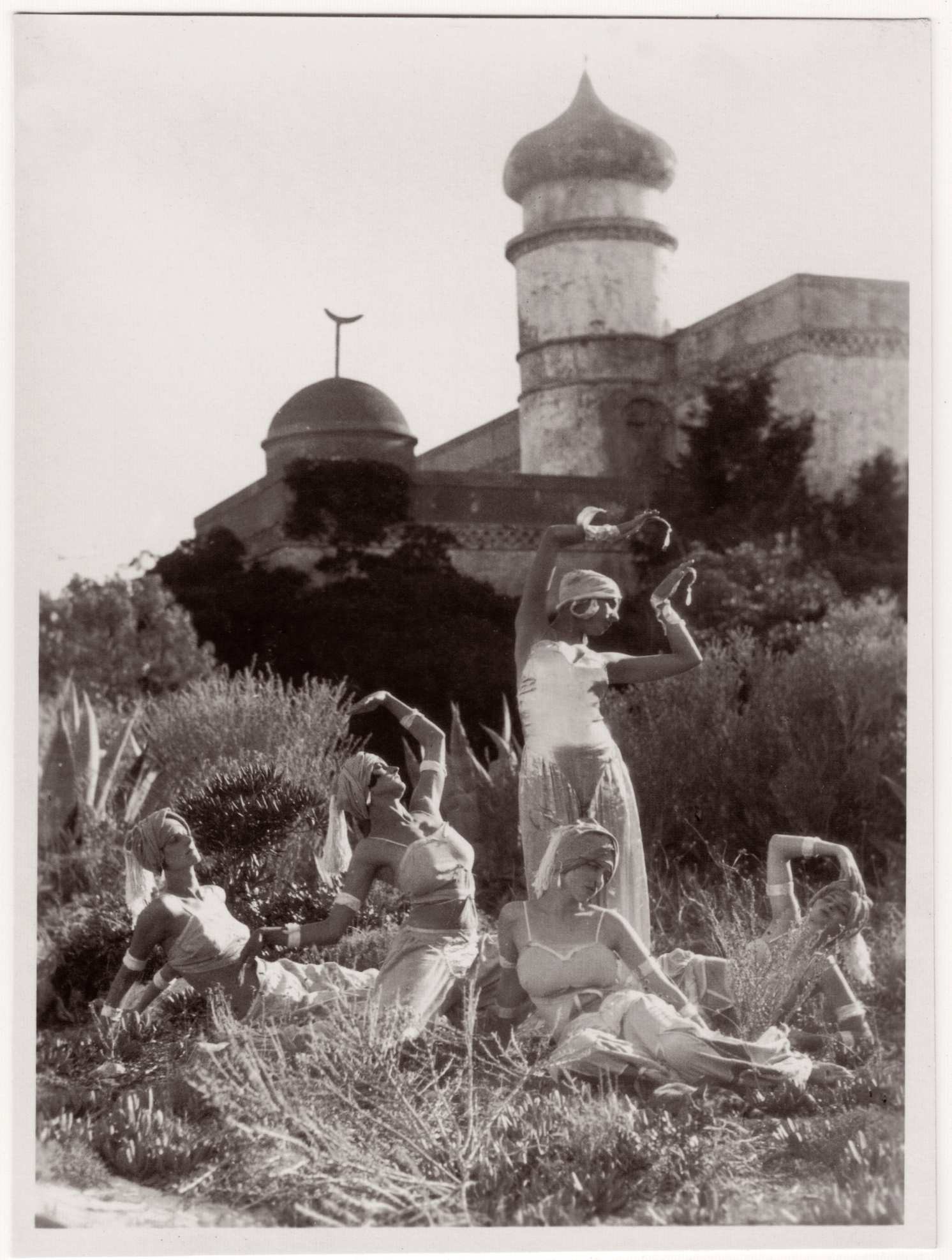

Over the season, students would rehearse in the day, dancing in the woods, and often break for picnics, sunbathing or cooling down by swimming, “hurling themselves from the highest of the jagged white rocks, turning graceful somersaults”. A significant visitor was the British painter Paule Vézelay (in fact, her 1923 linocut Bathers was made in London after her visit), along with a host of other artists and dancers, musicians and conductors who would come to stay, occasionally giving lectures or hosting evening events at the lively school.

Life on the French coast, with its luxury hotels, wealthy expatriates and rarefied, decadent lifestyle was captured by F Scott Fitzgerald in Tender is the Night , his heady analysis of the “Lost Generation”. The popularity of the destination has been understood to be due to the influence of the wealthy American expat couple Gerald and Sara Murphy (the inspiration for Scott Fitzgerald’s novel), who threw lavish parties at their house Villa America, and have even been credited with coining the phrase “sunbathing”. “Margaret Morris’s troupe of Chelsea intellectuals outnumbered the Murphys and their guests in Antibes that summer,” Emerson contends, “with Picasso and the Murphys attending their performances at the Hôtel du Cap. Indeed, Fergusson and Morris were on the Riviera as early as 1914, persuading their own ‘Murphy’ (the Kodak millionaire George Davison) to buy a house on the coast in 1919.”

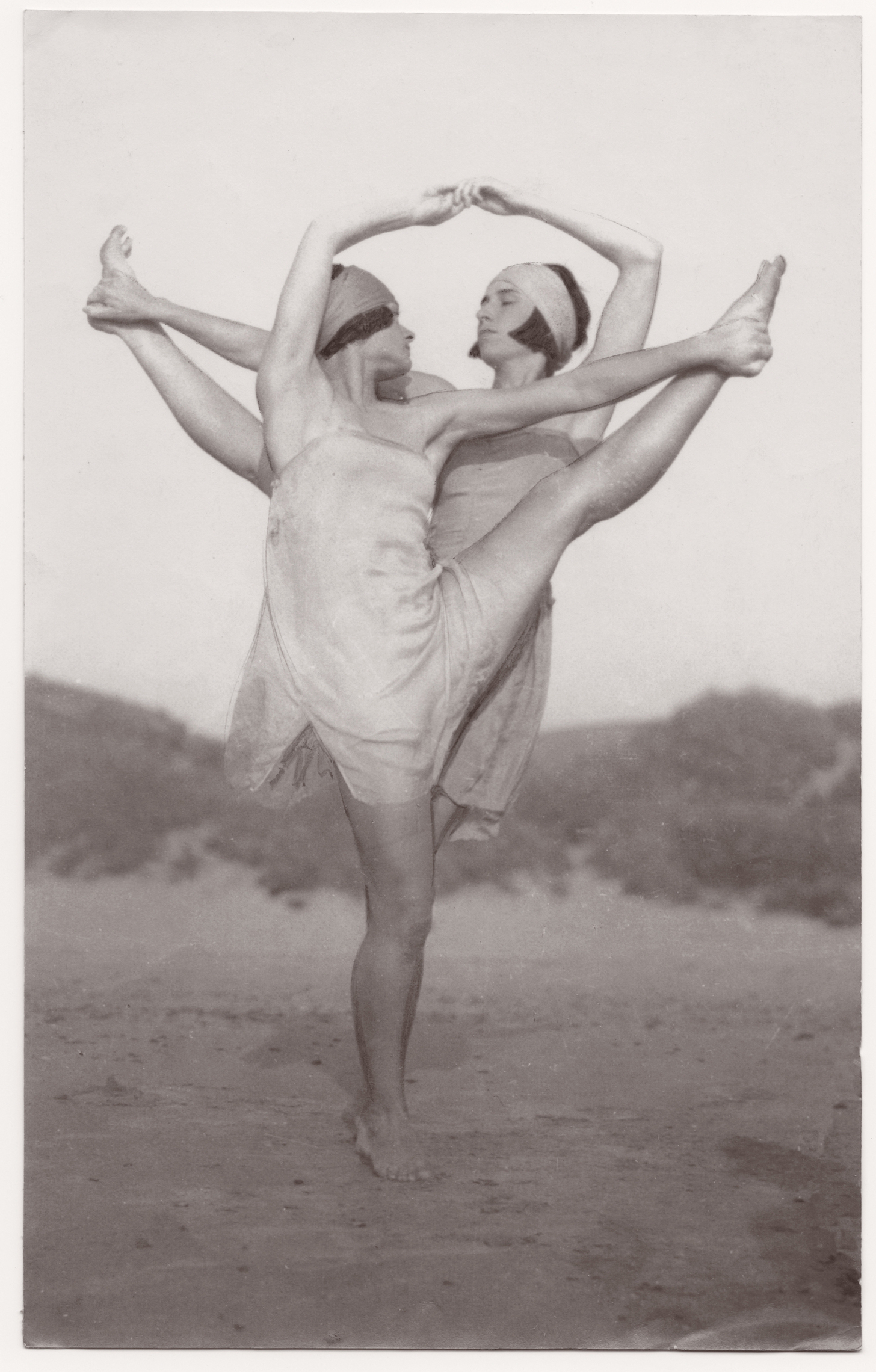

In 1924, Vanel and Hutton split from Morris and set up a separate school and dance company, the Studio Rythme et Couleur, in the nearby village of Saint-Paul-de-Vence. In their manifesto, Vanel wrote that she “wanted to see dance freed from its conventions, giving greater importance to the dancer itself as an artistic material, seeing in the dancer lines, shapes and movements and a material, worked like stone or clay, but into which humanity has been kneaded”. Bodies should be abstract forms, and rhythm taught without music. They travelled across Europe, performing at theatres in Paris, Brussels and Rome, but returned to the south of France in 1929 to open a theatre again in St-Paul.

“Bodies should be abstract forms, and rhythm taught without music”

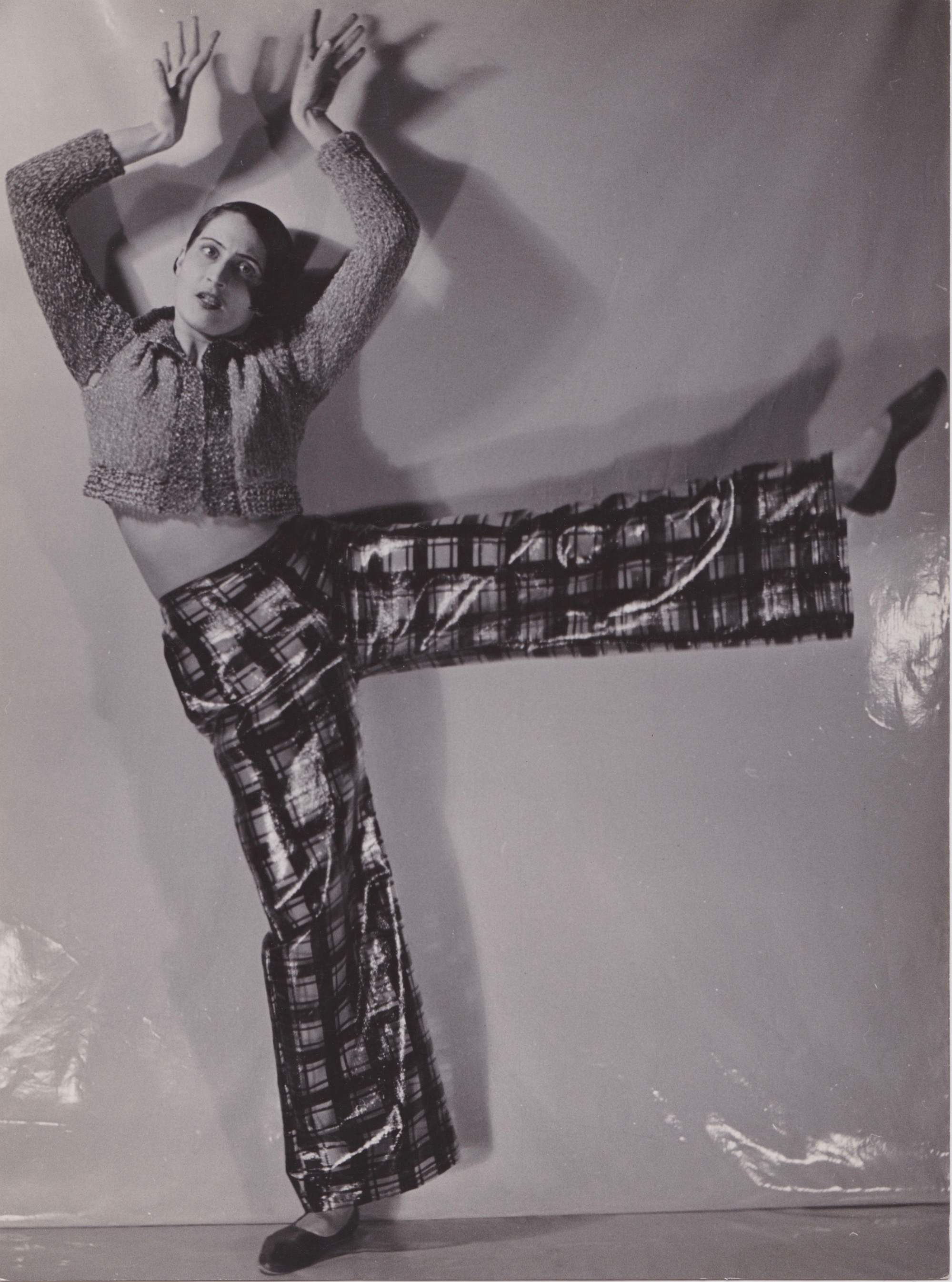

Vanel moved to Paris in 1934 and opened the Théâtre Hélène Vanel de Saint-Paul à Paris. Her split with Hutton became front-page news. “So are the ‘Danseuses de Saint-Paul’, as they used to be called when they were ‘Siamese twins’, now separated forever? In any case, [they] each continue to devote themselves to their difficult and bizarre art … two of Dance’s ‘originals’, of Life’s ‘eccentrics,’” published the April 1937 issue of The American Dancer.

Vanel participated in the 1938 International Surrealist Exhibition in Paris, meeting other important female artists of the surrealist period, like Sheila Legge and Eileen Agar, and collaborating with Salvador Dalí. Her collaboration with Dalí has been, until now, a footnote, but her presence was such a draw for contemporary audiences that her name (alongside André Breton’s) was the only legible piece of writing on the deliberately scrambled design of the invitation. Later in life, she reinvented herself as a lecturer at the Louvre, and subsequently as a sculptor and painter in Paris, dancing until her death aged ninety-two.

Hutton stayed in St-Paul, becoming a key figure of the cultural scene there and regularly hosted international guests, even referred to as “the founder” of the village by an article in Paris Match in 1950. She opened a new theatre in the 1950s and kept in touch with Morris through letters and intermittent meetings. By the 1960s, Hutton began to suffer from anxiety and psychoneurosis, and was eventually taken to England to live in a private institution in Harrow, where she was treated until she died in 1972. Vanel had been told that she had died in 1966, while Morris was never told. In Vanel’s memoirs, which omits her decision to both break away from the Margaret Morris School and her separation from Hutton, she wrote, “I am very embarrassed to continue what must be called my ‘memoirs’. For all of life involves changes, breaks, and sometimes abandoning people, and you suddenly find yourself on a rocky, thorny path where you feel pain and where you do not like yourself.” Morris went on to establish the Celtic Ballet Club in Glasgow, which would later become the Scottish National Ballet, and her system of movement notation—danscript—is still practiced across the world today.

All three women were financially and creatively independent, which facilitated their integration within the cultural vanguard of the period. Dance was one of the few areas during that period where women could develop their art without any dependence on men, especially if they ran their own theatres, which Morris, Hutton and Vanel did. In terms of their personal lives, Morris had a progressive open relationship with her partner, the Scottish colourist artist JD Fergusson, while Vanel and Hutton lived openly as lovers in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Hutton’s diaries indicate that she also had a relationship with the American poet and playwright Edna St Vincent Millay, and suggest that her and Morris had a romantic affair.

These accounts provide historical examples of the grey-scale of sexuality and are interesting in terms of relatively unfettered early-twentieth-century lesbian relationships, important queer stories that have been suppressed and omitted by a selective history. Parallels could be drawn with Andrea Weiss’s cultural biography Paris Was a Woman: Portraits from the Left Bank, which traced the lesbian and bisexual figures of the Parisian 1920s avant-garde, including Colette, Gertrude Stein, Alice B Toklas, Sylvia Beach and Djuna Barnes (who was a friend of Vanel and Hutton).

“These accounts provide historical examples of the grey-scale of sexuality and are important queer stories that have been suppressed and omitted by a selective history”

This text barely scratches the surface of Emerson’s rich and extensive study, with multiple performances, exhibitions, events, parties and meetings all brought to bear. It is over 600 pages long, and interspersed with plates of notable photographs, artworks and archival documents, and uses letters, journal entries, memoirs and criticism of the period to trace the prolific and fascinating history of these three figures. In the contemporary zeitgeist, where some of the most exciting work is often collaborative or multidisciplinary, and where the mediums of performance and dance have ruptured traditional understandings of modern art, it seems particularly pertinent to bring the stories of these dynamic women to the fore and celebrate their multifaceted life and work.