A bustling commercial street in the heart of Kyoto is the latest subject of self-taught Senegalese photographer Omar Victor Diop. Commissioned as part of photo festival Kyotographie, the project is the result of a residency staged at the end of 2019, just before the pandemic hit. Diop got to know the shopkeepers on the Demachi Masugata Shopping Arcade, before staging portraits with a number of them. He conjures their livelihoods through carefully selected props and wares, and the resulting images burst with the textures and patterns of signage, textiles and consumer products.

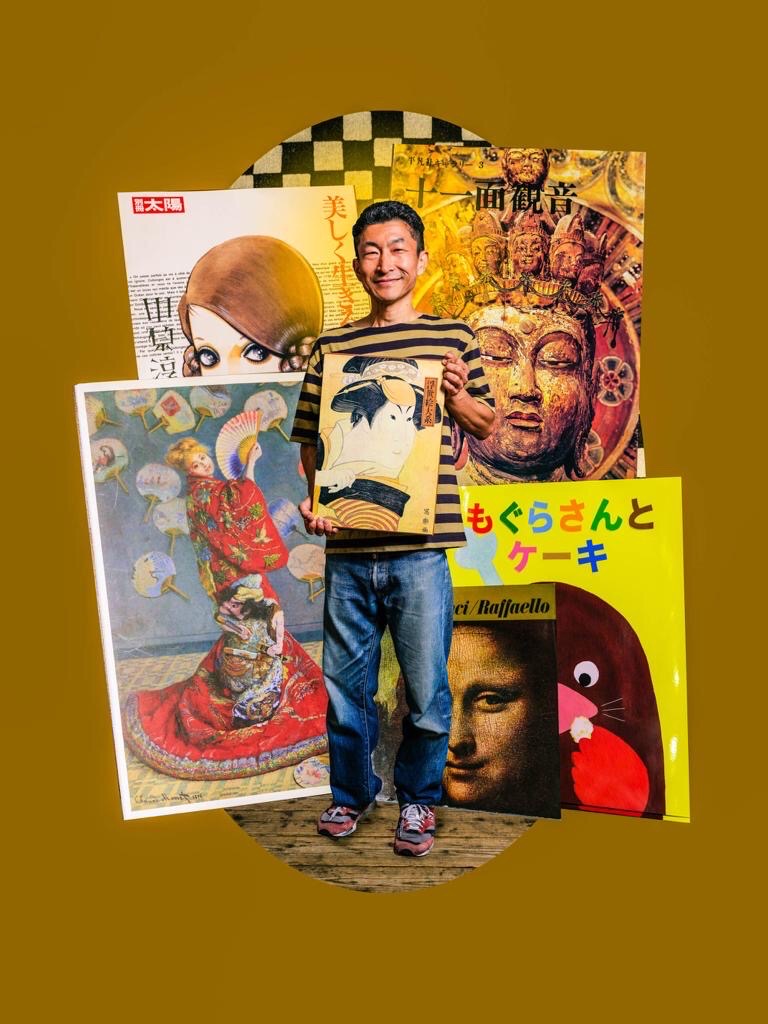

A fishmonger, watchmaker, greengrocer and sushi chef are all featured in playful studio shots that make bold use of block colours and cutouts. Diop’s subjects smile and strike a pose, relaxed before the lens but ready for the click of the camera shutter. There is an element of kitsch to the portraits, featuring oval-shaped frames of the kind that might enclose a family portrait that sits on a mantelpiece at home. Diop nods to the canon of twentieth-century Western African studio photography in much of his work, with a keen understanding of pose, pattern and composition, following in the footsteps of greats of the genre like Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keïta.

“I was surprised to see that there are more similarities between Senegalese and Japanese culture than there are differences”

Until now, Diop has turned his lens on African subjects, stating that his portraits are “a reinvented narrative of the history of Black people, and therefore, the history of humanity and of the concept of freedom.” In his 2014 Project Diaspora, he used photography to represent stories of black power and resistance from different countries and eras, challenging the monolithic history of Africa. While he appears in these portraits, he has stated that they are not self-portraiture. Instead, he performs the roles and lives of others, although their stories undeniably connect with his own experience of growing up in Dakar.

“I was genuinely surprised to see that there are probably more similarities between my Senegalese culture and the Japanese culture than there are differences,” Diop states in an interview with Claude Grunitzky, published in the festival catalogue. “The moment that struck me most was the morning, with the same rituals you would see in a Dakarois market, the smiles and the small talk between the merchants, the little attention paid to the regular customers. This made me feel like I was in Dakar.”

Project Diaspora will be shown in Kyoto alongside Diop’s study of the city’s shopping arcade, while a digital version of the project is available to explore online. A detailed 3D rendering of the street can be explored, featuring the busy shopfronts where discounts, new products and special offers are all announced in brightly-coloured neon and hand scrawled signs. Banners featuring the portraits are hung in the market itself, jostling for space with the signage and adding to the busy local landscape.