In the National Portrait Gallery, there is a painting of the infant King Charles II that shows him clasping an odd-looking device. It’s a curved piece of coral attached to an elaborate grip that contains a rattle. From the seventeenth century to the nineteenth, coral was given to children not only because it was thought to soothe painful gums, but also because it was believed to ward off evil spirits. Charles has the swollen, flushed cheeks of a child in the throes of what his contemporaries would have called not teething, but rather toothing, dentition or the “breeding of teeth”. Equipped with his coral, and with a puppy on hand for extra comfort, he seems content even if not entirely at peace.

My first encounter with this portrait was my introduction to devices of this kind, which I’ve since noticed in quite a few other paintings. One example is William Hogarth’s oil of the young Lord Grey and Lady Mary West, in which the male sitter is again holding a dog—this one squirming as a result of being tormented—while Lady Mary dangles the almost provocatively shapely coral. Another, which can be seen in Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, is William Jennys’s portrait of the wife of Vermont attorney Cephas Smith and their child: the sitters appear tired and severe, and the child brandishes the teething device defiantly. A little more appealing is Joseph Highmore’s Mrs Sharpe and Child; the teething baby, as in Jennys’s painting, looks apish, but Highmore is a superior technician, and the pink of the coral is picked up in the details of the baby’s sash and bonnet.

These days teething babies tend to be given Calpol or a rubber ring that’s been cooled in the fridge. My daughter Athena, who’s now sprouted her first four teeth, has a rubber giraffe that she likes to suck, but she’ll gnaw on just about anything—a plastic plate, my finger, her toy xylophone. Miniature rice cakes or segments of tangerine are also welcome.

When Athena began teething, a couple of friends recommended getting her a necklace of amber beads, which they claimed had analgesic properties. My wife and I were sceptical, and we thought in any case that it posed a choking hazard. In reading up on amber beads, I learned about other remedies that used to have their boosters, such as a bag of woodlice to be worn from the neck and an amulet consisting of a mole’s foot wrapped in a piece of cloth.

Medicinal treatments that were once ubiquitous now sound treacherous. A particularly popular one was Mrs Winslow’s Soothing Syrup. Mrs Winslow was a nurse from Maine whose son-in-law eagerly marketed her homemade remedy; first available in 1849 and sold in Britain till 1930, it contained morphine sulphate. An earlier elixir, Dr Godfrey’s General Cordial mixed opium and alcohol, and until the 1950s an ingredient of commercially produced teething powders was calomel, a compound of mercury.

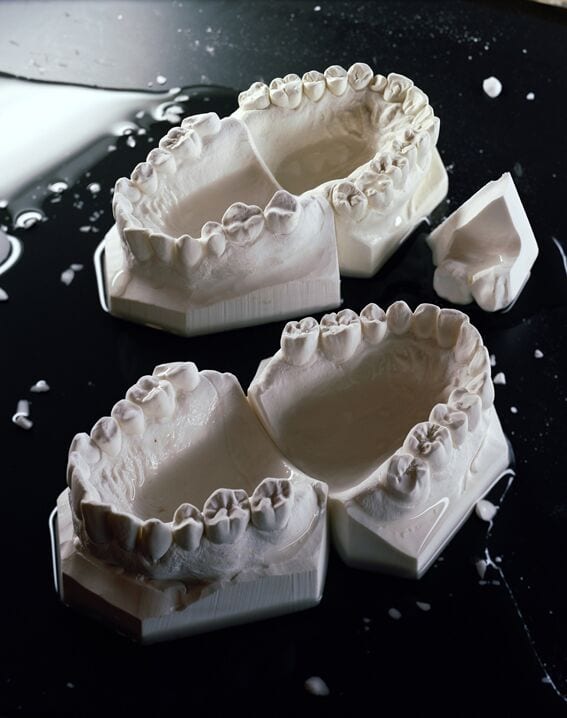

Right: Enamel Support, 2015. C-Print on aluminum; framed 78 x 61.5 x 3.5 cm © Torbjørn Rødland. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Eva Presenhuber, Zurich / New York

“Teeth are a record of our experiences, not least our choices about what to put in our mouths”

Searching online, I’ve found old advertisements for Mrs Winslow’s product. One of these, emphasizing that it “soothes the child” and “gives rest to the mother”, includes verses warning “If you don’t give him Mrs Winslow’s Syrup you’ll see”. Another declares that “A mother’s kiss is not half so soothing to baby as Mrs Winslow’s Soothing Syrup”.

For parents, a baby’s mouth is a source of worry because, despite our seeing and especially hearing a lot of symptoms of the changes taking place, we can struggle to tell what’s going on in there. At the same time, thinking about this process sharpens or reactivates our own oral anxieties. Teeth are a record of our experiences, not least our choices about what to put in our mouths. They can seem determined to betray us: they are a point of aesthetic concern, on account of the social pressure to achieve pearly perfection, and we’re aware that they will survive long after we’ve died and most of the rest of our body has decayed. We wonder too if, despite their helping make the nutrients in food accessible to us, they perhaps aren’t ideally suited to dealing with the foods we actually want to eat. We associate them with biting and chewing, yet also with grinding, snarling, eruption and impaction. For many of us, monitoring the emergence of a child’s teeth is a reminder of past struggles between patient and dentist—a narrative of conflict coloured by films such as Tim Burton’s remake of Charlie and Chocolate Factory (where Willy Wonka recalls his dentist father cramming his mouth with metal apparatus) or Marathon Man (in which Dustin Hoffman gets a merciless grilling and drilling).

“Rødland repeatedly pictures the mouth as a sensitive organ and a mysterious space, a cavity that’s a theatre of both desire and discomfort”

Reflecting on all this dental disquiet, I’m powerfully reminded of the work of Torbjørn Rødland, who explores how teeth have become “a symbol for intuitive fears and irrational anxieties”. The Norwegian photographer has shadowed Danielle Heller Fontana, a Zürich dentist specializing in corrective work—dramatic procedures in which, to Rødland, it’s unclear whether “the hands reaching out are horny, healing or hurting”.

One of his most unsettling images is of a latex-gloved hand spearing anaesthetic into a raw-looking gum. Another is a photo of a smashed-up cupcake, mingling moistly with a spoon, a cashew nut and a selection of crowns and dental implants. Even glimpsing it makes me shudder; I feel the way I do when, very occasionally, a shred of silver foil finds its way into my mouth and eludes my rescuing finger. Rødland repeatedly pictures the mouth as a sensitive organ and a mysterious space, a cavity that’s a theatre of both desire and discomfort.

This isn’t what I want to have in the forefront of my mind as a teething Athena tries to consoles herself by biting the kitchen table. Yet as I coax her away from the table’s edge and look for her rubber giraffe among the flotsam of her upturned toy basket, I recall a chastening snippet I found in a nineteenth-century issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association: “It is not sufficient to say teething is a normal process and will take care of itself. Possibly it would if parents were normal.”