Storytelling is a guiding principle for Ben Edge. The London-based painter, who as a child spent weekends visiting his dad in a then-desolate Shoreditch, has long been obsessed by the hidden histories embedded within the city and beyond. Whether extracted from the pages of Peter Ackroyd books or retold by members of his family, a search for local folklore has come to dominate his creative practice, which has expanded to encompass distinct rituals that continue to thrive up and down the country.

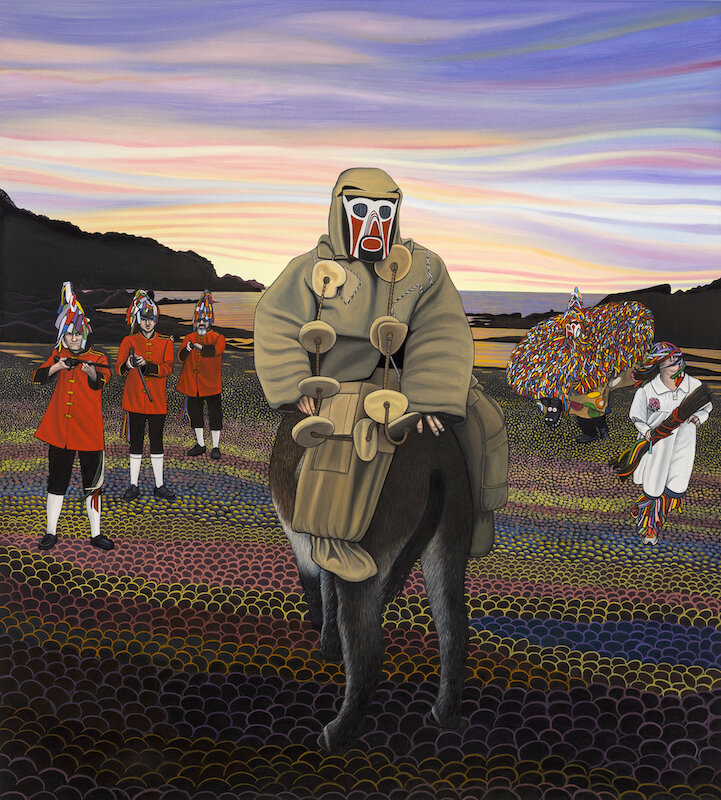

Edge’s painted scenes offer atmospheric vignettes showing mysterious ceremonies and collective celebrations. Some feel rooted in documentary, while others offer symbolic interpretations of particular mystical tales. The artist’s meticulous research is also distilled into accompanying texts that have developed into an informal archive, which will preserve the legacy of British folklore for years to come.

You have recently become something of a cultural historian as well as an artist, including detailed information about the history and legends that surround your subjects. Why did you first begin researching British folklore?

It began with a chance encounter about five years ago. I was travelling to the Tower of London to meet the Ravenmaster. I had long been fascinated by his role and was hoping to paint his portrait. You know the story goes that if the six ravens leave the tower the kingdom will fall? That is why they have one spare. On my way over, I encountered a ceremony held by the Druid Order right in the middle of the city. I couldn’t believe my eyes. Witnessing that set me on this path, to discover ancient rituals and traditions that are still being performed today, across London and beyond.

“Folk tales are a great space for conjecture, which is ideal for an artist”

Discovering folk history is fascinating because it is an alternative to the British identity crisis, grappling with the idea of what Great Britain is, and all of its political implications. These are rich, local stories that are deeply entrenched in their individual communities. They were born out of a need to connect with one another, and even if the original story has been lost, the ceremony and the connection found within it is what is remains important.

- Ben Edge, The Mari Lwyd, 2019 (left); The Summer Solstice, 2018 (right)

A lot of your paintings celebrate the fact these traditions still exist. An image of cloaked druids or figures in folk costumes might seem to be from another time if it were not for your inclusion of smartphones, skyscrapers and the like. Is it important for you to portray these customs as alive and well?

It is really important. Folk traditions hold a mirror to contemporary society, and they can ignite changes in political conversations. A prime example is the Morris Federation’s decision to ban dancers painting their faces black. Many people will tell you that this form of ‘black face’ predates colonialism and relates to warding off spirits, but the question remains: does it cause offence today and is that acceptable? It brought up some really important conversations around race that might not otherwise happen within the community.

It is also worth noting that most folk traditions come from the ground up. These are working-class histories that date back to the idea of peasants taking control of their own existence, by doing something such as praying for a good harvest. Often these histories were not written down because they were not deemed important, so the stories evolve and change. It is a great space for conjecture, which is ideal for an artist. I am taking part in a group show at Gallery 46 called Queer As Folklore in May, which demonstrates how important it remains to this day.

I have heard that storytelling is a very important part of your life, how so?

I grew up in a very eccentric family. They are all big storytellers: my grandfather believed in the Green Man [a mythological figure of rebirth and regeneration]. Grandad worked in Smithfield Market and always had so many stories to tell about that area of London. He was also a part-time animal handler: his tiny council flat was filled with snakes, lizards and tarantulas. Back in 2009, I painted his portrait, which ended up being selected for the BP Portrait Award. It was a relief because I was painting what I know, whereas at art school I was always worried about where my next idea was coming from. I spent too much time worrying about being clever. Uncovering all of these folk stories feels like carrying on the family tradition. I have found myself, in a way.

“These are rich, local stories that are deeply entrenched in their individual communities”

Is it right that you’ve recently begun expanding your medium beyond painting, making a documentary, and collaborating on an exhibition with the Museum of British Folklore?

It’s the next logical step, because I have gathered so much material during my research. Using film, for example, snaps you out of a fairy tale and into reality. I first met the museum founder, Simon Costin, following a talk he gave in Hackney. He is an incredibly talented set designer, having worked with people like Alexander McQueen and Tim Walker. The museum has no permanent home, but we wanted to create a ‘museum’ experience that immerses people in these stories. After a couple of galleries fell through, we decided to do it ourselves at The Crypt Gallery in St Pancras Church. It is a pretty fitting location.

- Ben Edge, Hunting the Earl of Rone (left); The Garland King (right)

One of the more unexpected outcomes of the pandemic seems to be that people are taking more of an interest in their local area, as opposed to always looking further afield. Do you think there will be a renewed interest in these localised stories?

I love the idea of the distinct, localised experiences you can have, whether you’re exploring a culture from where you grew up, or elsewhere. It is an antidote to globalisation, because everywhere has its own quirky traditions. For me, travelling around the country to witness these customs, and reconnecting with nature in the process, has been so important and freeing.

That being said, I also love the idea of pilgrimage, and the concept of one specific place holding significant spiritual value. When I visited Stonehenge during the Summer Solstice, I met a woman who had travelled all the way from Russia. It reminded me to appreciate the amazing places I have right on my doorstep.