It’s strange for an artist to be defined by a single artwork. It is stranger still if that artist works across a range of media, and is also an author, a teacher, a feminist and an activist. As pleased as Judy Chicago is about the (positive) attention The Dinner Party (1974-79) has received over the years, the 82-year-old still hopes to live long enough to see the rest of her work emerge from its shadow. As the first full retrospective of her career opens at the de Young Museum in San Francisco, it looks like Chicago’s other remarkable creations are finally creeping into the light.

The Flowering: The Autobiography of Judy Chicago is billed as an answer to and a reflection of the first two volumes of the artist’s autobiography, Through the Flower (1975) and Beyond the Flower (1996). Written during the pandemic, and introduced by Gloria Steinem, it is both an update of Chicago’s story and a call to action, for art that contributes to a just and equitable world.

The Flowering is a chronological tale that weaves together the personal and the professional, beginning with Chicago’s upbringing as Judy Cohen. Her parents were Jewish liberals who instilled in her a sense of social justice and the idea that “the purpose of life is to make a difference”. It didn’t occur to her that her artistic aspirations were “either peculiar or unobtainable”.

It wasn’t until graduate school at UCLA that Chicago began to feel that the art world might not be ready for her. “Fortunately,” she quips, “I had a tendency to pursue my own objectives regardless of the societal messages I received.” Elsewhere, when she describes her reputation for being confrontational (“‘Direct’ would be more accurate”), you can almost see the smile tugging at her lips.

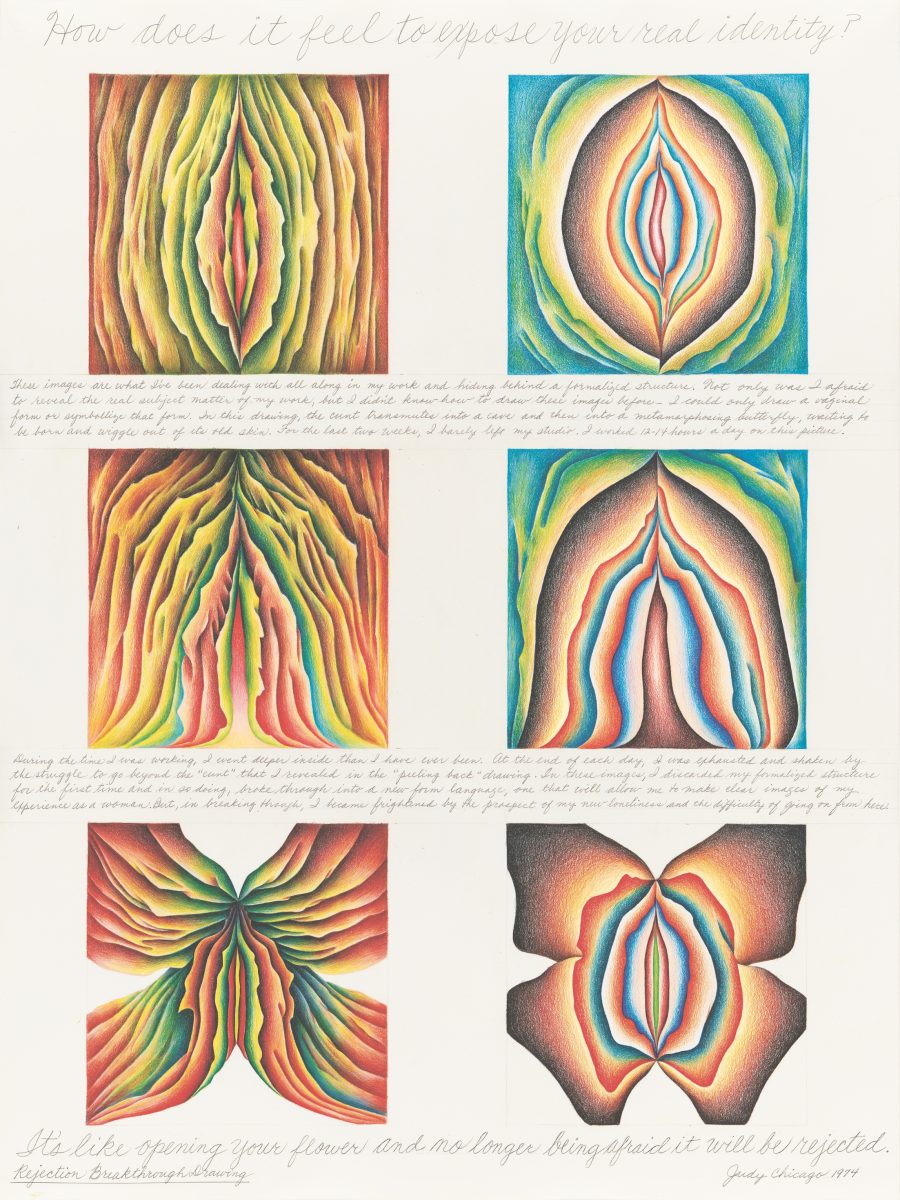

And yet, there’s also vulnerability here. Chicago writes of learning to survive in a “rough-and-tumble male-dominated world”. Initially, when male painting instructors knocked her art’s graphic emotional and sexual subject matter, she tried to suppress it. She struggled to be herself: “Being a woman and an artist spelled only one thing: pain”.

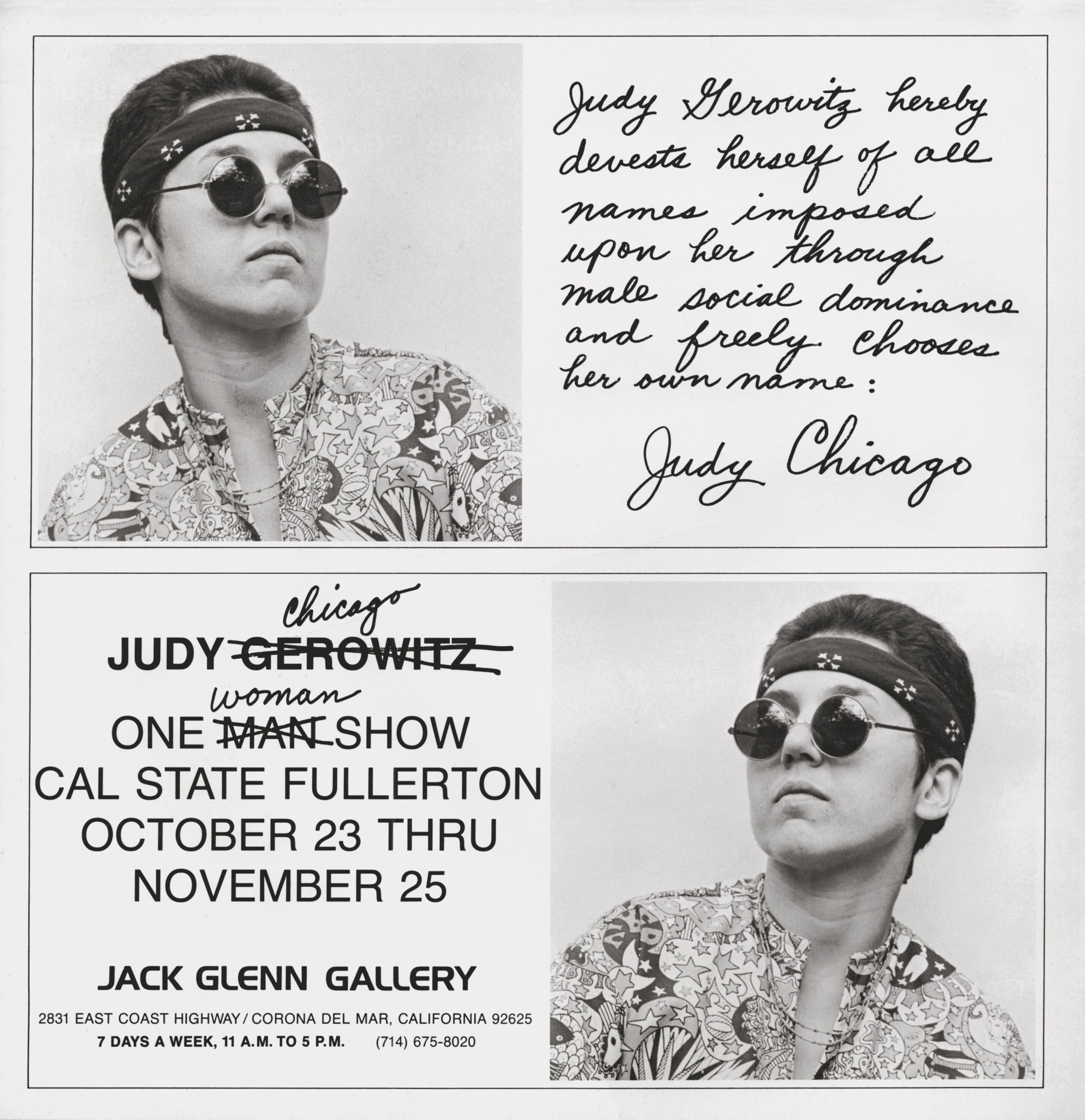

As the women’s movement gained momentum, she found others putting into words the feelings she had been grappling with: “If the art world as it existed could not provide me with what I needed, then I would have to commit myself to creating an alternative.” In 1970 she changed her name to Chicago, “in order to identify myself as an independent woman”.

“Chicago struggled to be herself: ‘Being a woman and an artist spelled only one thing: pain’”

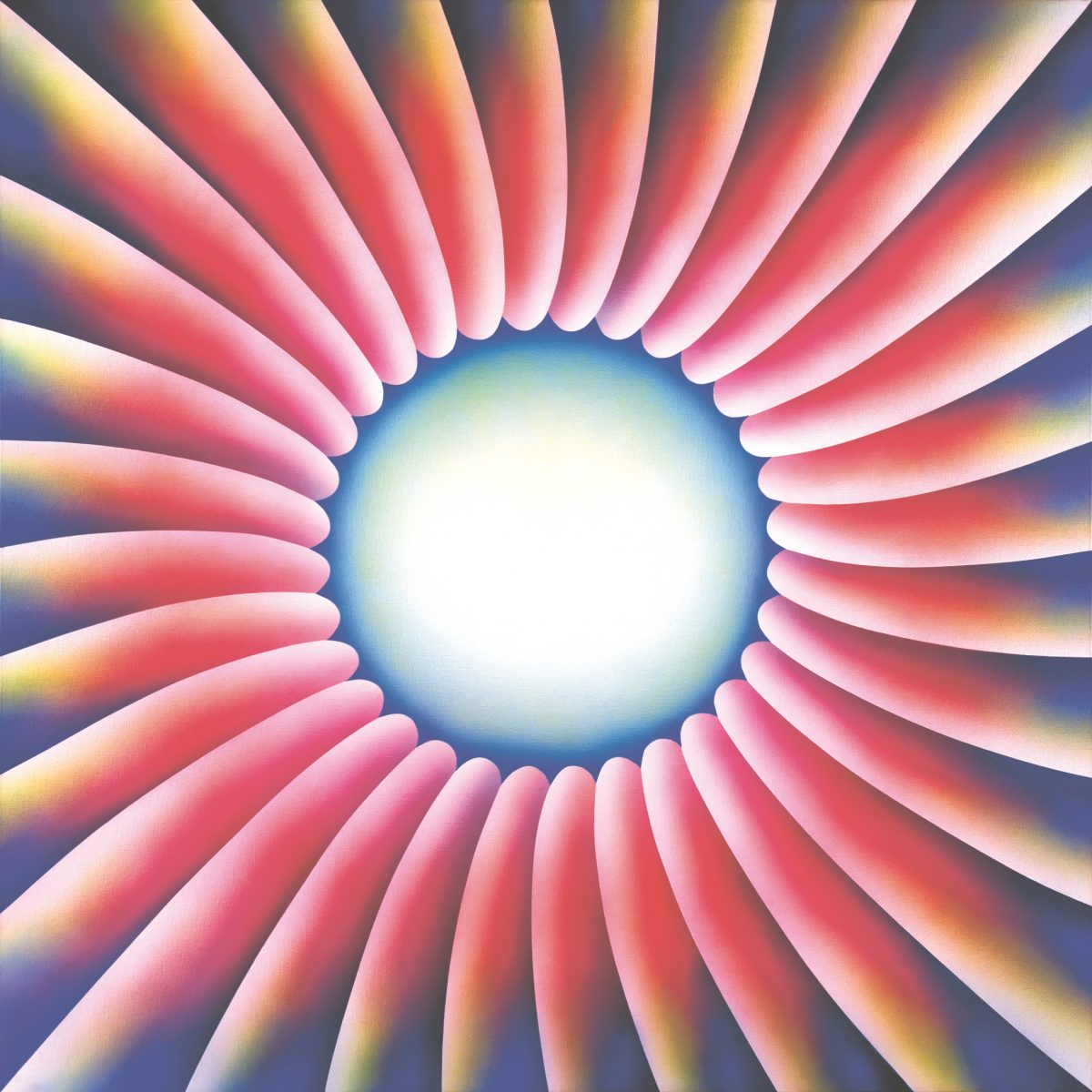

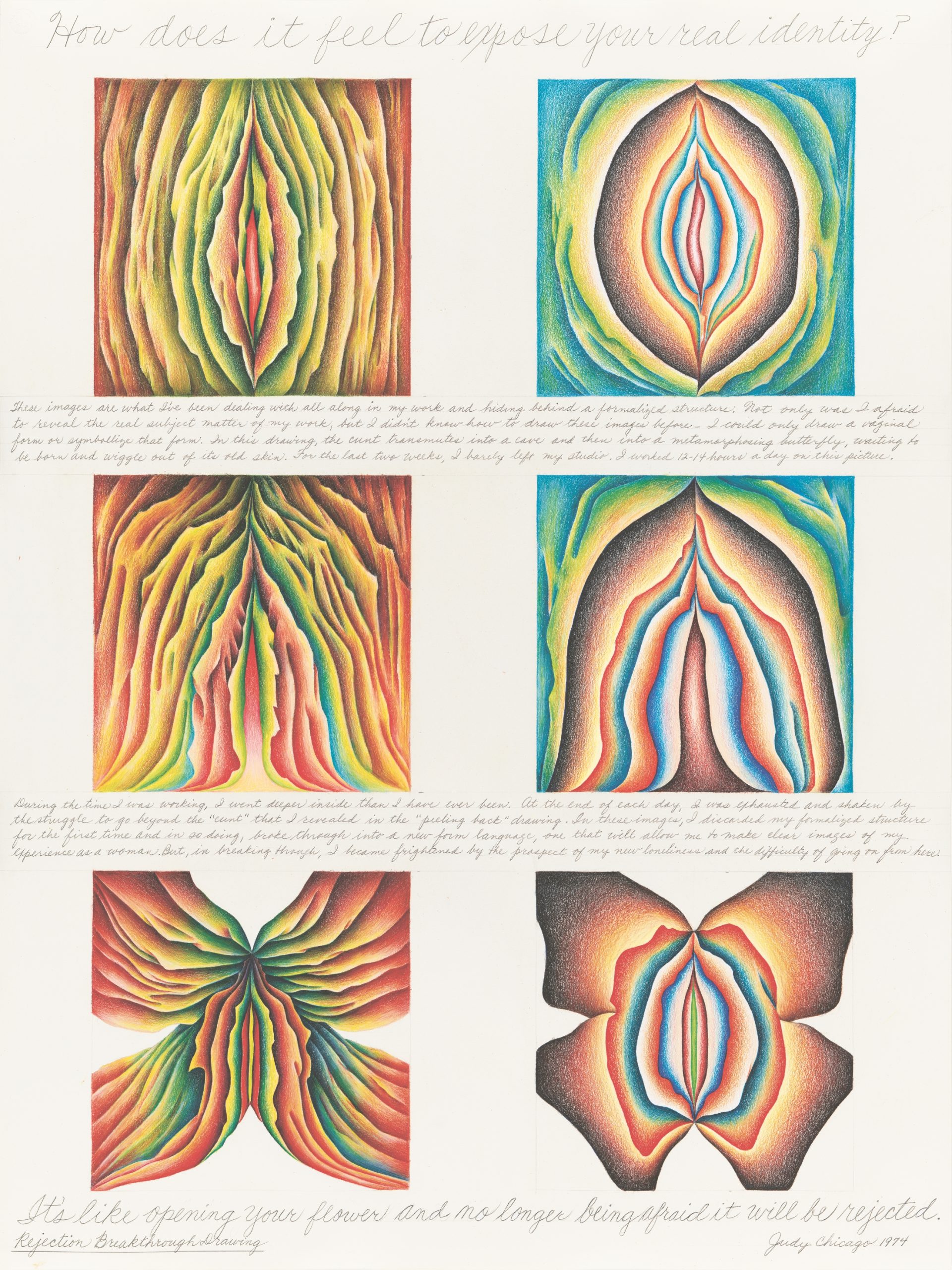

Moving away from the minimalist art she made in the 1960s, Chicago returned to painting and learned to “expose rather than cover up” her content. She began teaching young women and developed the Feminist Art Program, which sought to address the gender imbalance in the art world. Chicago’s writing on feminist values is among her strongest, especially when expressing her belief that feminism promotes “personal empowerment, something that, when connected to education, becomes a potent tool for change”.

Together with Miriam Schapiro and others from the Feminist Art Program, she organised Womanhouse, a feminist installation that opened in Los Angeles in 1972. In her foreword, Steinem describes her own visit: “This was my first experience of inclusive art. I was no longer just the object of a painting or a sculpture, but a female human being with a life.”

Critical responses to Chicago’s work haven’t always been encouraging. Despite the positive public reception, The Dinner Party was “a work that everybody wanted to see but nobody wanted to show”. Chicago describes the piece as a test, “to see if a female artist working at the level of ambition generally reserved for men would be equitably supported by the art system. The answer was a resounding NO”.

The second half of The Flowering whisks the reader (a tad too briskly) through the rest of her travels, relationships and bodies of work. These include The Birth Project (1980-85), which sought to “reconnect art to the fabric of human life”; The Holocaust Project (1985-93), a collaborative project with her husband Donald Woodman, focussing on “how such horror could have been inflicted on people by people”; and her most recent work, The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction (2012-2018), which grapples with the damage human beings inflict on our fellow creatures.

“The Dinner Party was ‘a work that everybody wanted to see but nobody wanted to show’”

As Chicago reflects on the past 25 years, she writes candidly about being so focused on issues of gender that she neglected to explore the work of women artists and writers of colour (“An unforgiveable omission on my part”). At first, she believed all injustices to be a consequence of sex, but now she understands that ‘the art system is unjust to both female and male artists, particularly if they are minorities’.

What now? Chicago doesn’t pretend to have all the answers. Since the permanent housing of The Dinner Party in the Brooklyn Museum, she has gained more traction, but even now, she writes, with newfound popularity and powerful gallerists behind her, “the upper echelons of the art world remain beyond my reach […] the long-term preservation of my art is not assured”.

And so, she will simply do what she has always done: “Go back into my studio and try to wrest some meaning from life and the many challenges it presents”.

Chloë Ashby is an author and arts journalist. Her first novel, Wet Paint, will be published by Trapeze in April 2022

Judy Chicago, The Flowering: The Autobiography of Judy Chicago

Published by Thames & Hudson, out now

VISIT WEBSITE