Sam Moore describes his conversation with artist Huang Po-Chih about his new exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in London, and what it means to be a “collaborator” with his subjects.

Meaning seems to be in constant flux within the art of Huang Po-Chih, existing at the intersections of documentary and autobiography and between the material conditions of labor (as well as more abstract ideas of self-expression). These ideas became even more complicated during our conversation. The aid of a translator allowed questions and answers to flow but also carried with it another point of tension—one between intent and interpretation. Translation itself is not an exact science.

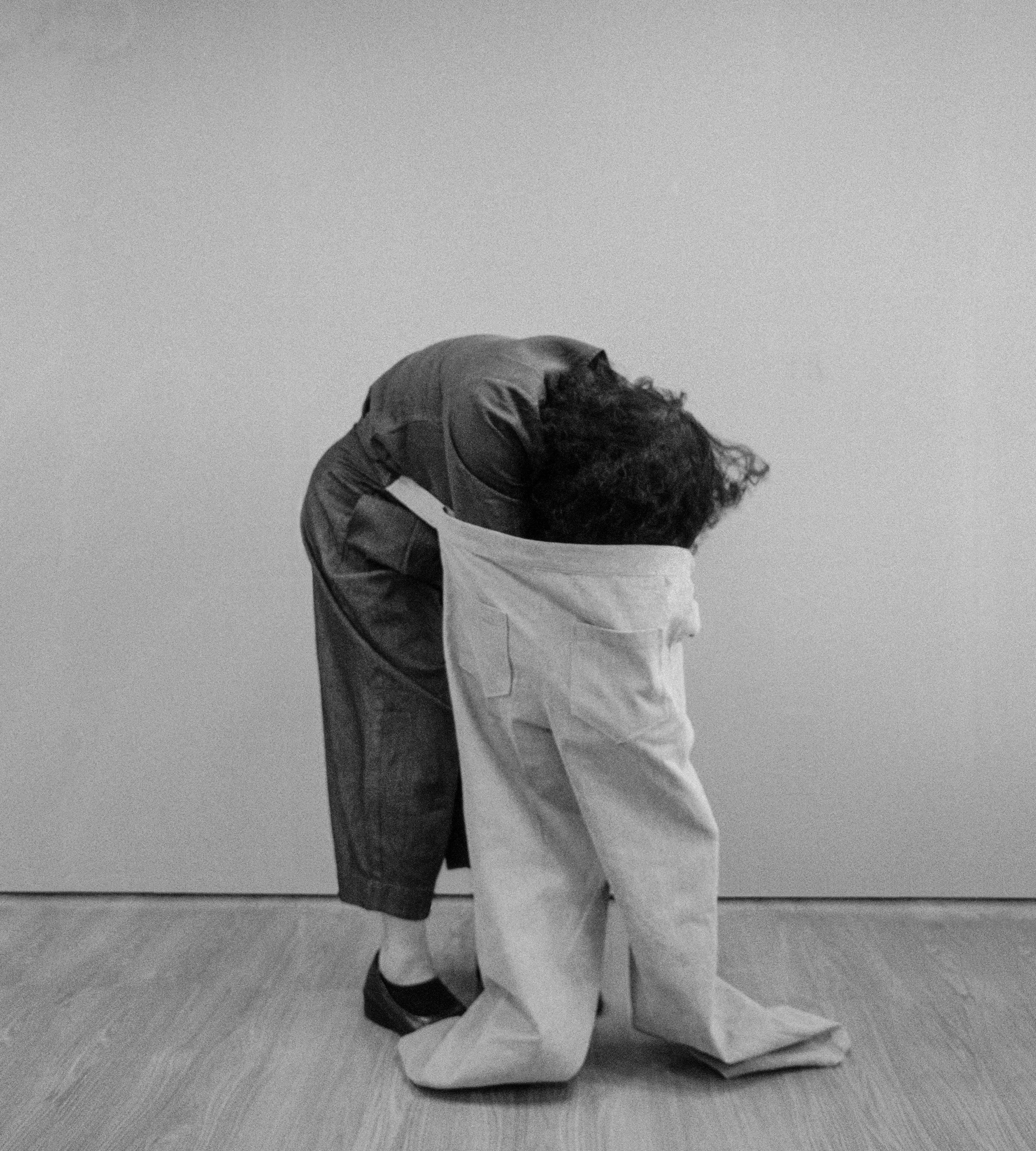

The first knot that becomes clear when engaging with Waves, Po-Chih’s new exhibition at the Hayward Gallery, fittingly, emerges through clothing. Much of Po-Chih’s work is informed by the experiences of garment workers in textile factories, a context which is made materially clear in images like Mrs. Kim – I’m hiding from the sweating rain, in which a figure submerges themselves in a pair of trousers, the clothing acting like shelter from a storm. For Po-Chih, this layering of garments on top of one another, is inseparable from the conditions of the people that he photographs. “The working conditions are pretty intense, the workload is heavy and everything is always rushed. So the garments just pile on top of the workstation, and they would just pile higher and higher and higher constantly.” The series from which this image is drawn—Blue Elephant— is also inspired by the things that Po-Chih’s mother told him: that the longer you sat down to sew, the more your hands and feet would swell. “She joked that you would always get elephant feet.”

In contrast to I’m hiding from the sweating rain are images like Mr. Ho – I am an elephant with my trunk raised high, asking questions, the name of the image making reference to the pose that Mr. Ho is striking. And rather than being buried under layers of garments in the way that Mrs. Kim is, Mr. Ho, with a shirt on backwards, reveals his bare back to the viewer. For Po-Chih, “the nature of exposing the back kind of equalizes everyone,” saying that it “doesn’t matter if you’re a garment factory worker under layers and layers of clothing, or if you’re going on a night out, often people still expose the back.”

It’s ironic that in this simple act of exposure, so many of the things that seem to animate Po-Chih’s interest in clothing and the people that make them become revealed. He stresses the fact that by showing bare skin, the images are able to shed the socio-economic conditions that are so often associated with clothing, from “the color of the clothes, the materiality of the fabric […] as well as time and history and memory.”

Halfway through our conversation, we reach a linguistic stumbling block, trying to find the right word to describe people like Mrs. Kim and Mr. Ho who appear in Po-Chih’s images. These photos are often informed by the conversations that Po-Chih has with the garment workers—although it’s made clear that these are not “any kind of structured conversation, it’s very casual” —as well as sharing stories that he’s heard from other garment workers which could “inspire them to perform.” This is when Yung, the translator, uses the term “subjects” to describe the people in Po-Chih’s images, putting an emphasis on the agency that they’re given to express themselves. It’s because of this agency that we begin to wonder what the right word word could be, before settling on “collaborator,” simply because “the process is very collaborative.”

It’s through this act of collaboration, through sharing histories and how they might manifest in the images, that the driving force behind Po-Chih’s work becomes clearer. His practice is described to me as being something akin to documentary filmmaking, but rather than focusing on the lives of the workers, Po-Chih zeroes in on “documenting their thoughts, and the idea that everyone is creative. And the fact that the work they do is very standardized, the work they do doesn’t allow them to express their creative sides.” It’s through talking to the workers, and engaging openly with them in the process of taking the pictures, that Po-Chih aims to document their “creative outbursts.”

I ask if this dynamic, and the power that the open, participatory relationship between Po-Chih and his collaborators creates any kind of tension or uncertainty, but am told that he still maintains a certain distance. He says the process is “like hanging a painting; you have to get very close to it and then you step away.” I’m told that the relationship that his practice has with the idea of documentary filmmaking is “to do with time” – the idea that Po-Chih can spend more time on the ideas that interest him, and with the people that do so as well.

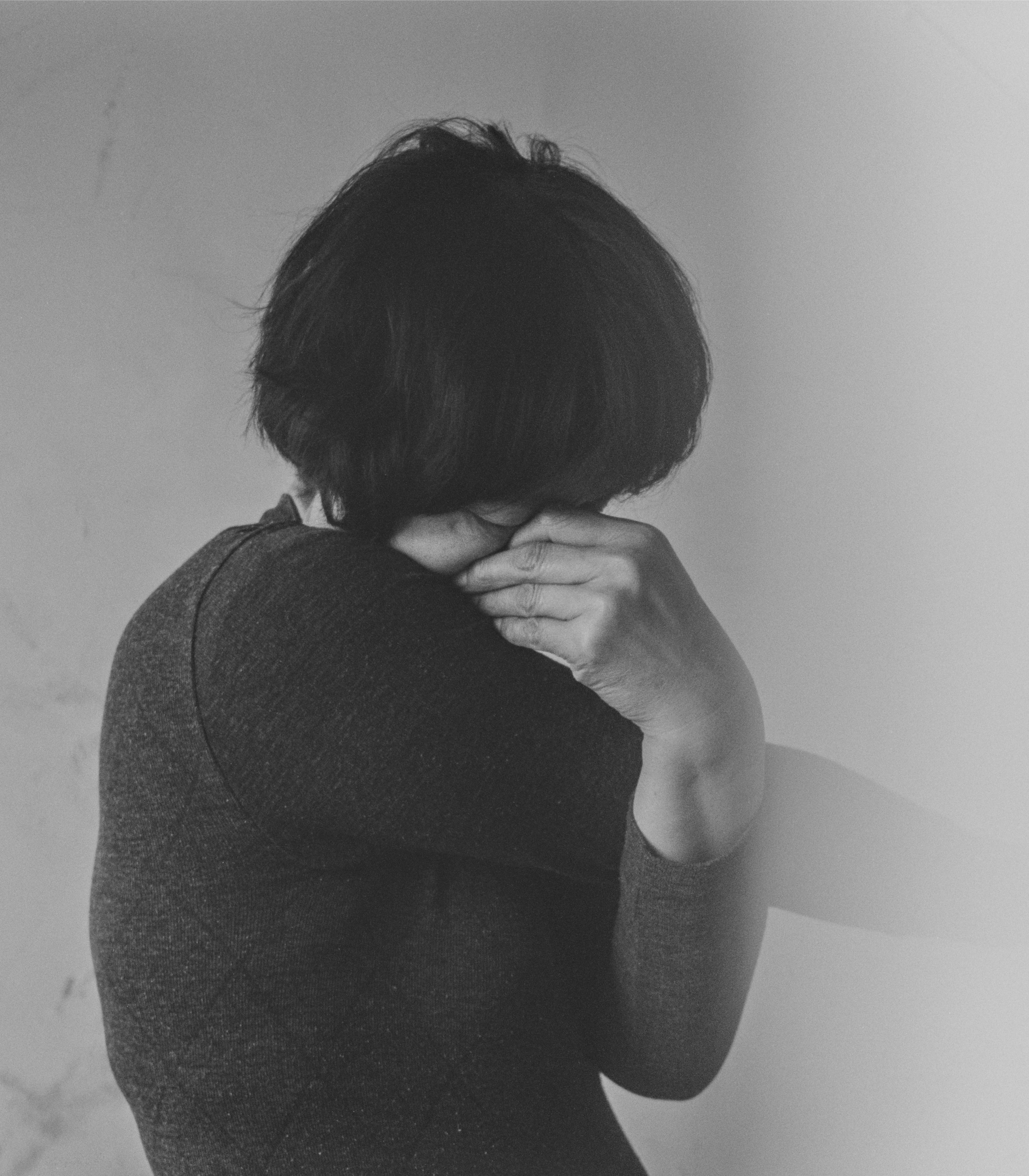

This is something that becomes abundantly clear when considering the relationship that the work has to the weight of history. In the image Mother – ‘Wanting falls around me. Heavy garment, but I can be a floating elephant in my dream.’ her eyes not meeting the camera directly and the heaviness given to the arm-as-trunk seems to carry with it the stories she and others like her carry with them.

Between this creation of a space for the exploration of creative impulses, and the more explicit ways in which images like I’m hiding from the sweating rain comment on the material conditions of labor, it could be tempting to give Po-Chih’s work the label of political art. This is something that I become curious about throughout our conversation, even as the artist pushes back against this classification. Po-Chih doesn’t wish for the work to have a kind of mobilizing political impact because the most important thing is being responsible to his collaborators, and sometimes, some participants collaborators have a situation that’s more difficult than others. And by hoping to have any material political impact or dimension to the work can be harmful to them.

Of course there’s the hope that things might improve for Po-Chih’s collaborators and those in similar situations to them, but it is far from the driving force behind this ongoing project. Po-Chih says that he doesn’t feel the job or responsibility of his practice is to “force change,” and instead that his intent is to bring forward different perspectives, in the hope that viewers will be able to respect them. There’s a clarity to what Po-Chih hopes viewers will be able to take away from Waves: the fact that “they are looking at human beings who are very similar to them.”

Words by Sam Moore

Huang Po-Chih’s show Waves will be up between 9 Oct 2024 – Sun 5 Jan 2025 at the Hayward Gallery in London.