Ralph Rugoff, curator of this year’s Venice Biennale, urged that through this international exhibition onlookers should “acknowledge at the outset that art is more than a document of its times.” The presentation of multiple perspectives in his central exhibition, May You Live In Interesting Times, promotes the diversity of ways to make sense of this world. Untold stories are no longer obscured, and reflections from previously subaltern voices resound. A canon of both emerging and established artists from the African continent and its diaspora hold a strong presence: Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Michael Armitage, Stan Douglas, Kahlil Joseph, Julie Mehretu, Zanele Muholi, Otobong Nkanga, Henry Taylor and Arthur Jafa (who won the coveted Golden Lion), among others.

The biennale’s notable inclusion of artists depicting African and black realities begs the question, is this an homage to the work of the late Okwui Enwezor? Enwezor, the curator of the 2015 Venice Biennale, died earlier this year. He remains remembered for his commitment to expanding contemporary art’s limits beyond established arenas and new hotspots in emerging locales. Before his death, Enwezor served as a strategic advisor to the triumph that is the newly-introduced Ghana Pavilion, curated by cultural historian Nana Oforiatta Ayim. Since establishing ANO Institute of Arts & Knowledge in 2002 in Accra, her mission has been to uncover and create new cultural narratives of the African continent, providing a space for interrogation and the fertile breeding ground for development at large.

Titled Ghana Freedom, the pavilion illuminates the unshakable reality surrounding access and affordability. For some, freedom is a physical achievement afforded by class, creed, financial mobility or education, but Ayim contests this view: “I’m not sure freedom is as universal a concept as some claim it is, and that was really one of the things I was interested in exploring in this exhibition. What does freedom mean to different people and through different lenses?”

Meanwhile, South Africa’s pavilion (named The Stronger We Become) landed during the country’s run-up to a national election; a time where collective consciousness and shared values are questioned, and a time of disillusionment and ceremonial shroud. Through the works of three South African artists, Dineo Seshee Bopape, Tracey Rose and Mawande Ka Zenzile, the pavilion examines the state of resilience—a state that has defined the nation’s history by way of the insitutionalized racial segregation, dispossession and impoverishment of certain communities that dwell within its borders.

From Arthur Jafa to Felicia Abban, Tracey Rose to Otobong Nkanga, these are the artists representing the black and African experience at Venice, and shaking up the Biennale in the process.

In artist and filmmaker, John Akomfrah’s three-channel film installation, The Elephant in the Room – Four Nocturnes, audiences are met with a barrage of scenes depicting human encroachment on the natural world. Images of destruction and the dismantling of ecological terrains abound. Sights of ecosystems disrupted symbolize capitalist man-made plunder. Deserted and displaced black nomads encounter one another with deadly stares as a sign of the enduring migrant crisis, which continues to cause contention through battles over ownership and rights to resources among African borders, and within Western locales.

Tracey Rose’s film, Hard Black on Cotton, references theatre and carnival custom through satire. Drawing on the codes of Black and African cosmological belief systems, the male South African actor plays a prophet, dressed in voodoo accoutrements as he recites incantations in Latin. He fails in his attempt to reawaken a historical mythic African icon, who if called upon will activate a great recollection of the lost past of Africa’s greatness. This film and its portrayal of mystic arts fill onlookers with feelings of insanity, intelligence and chaos.

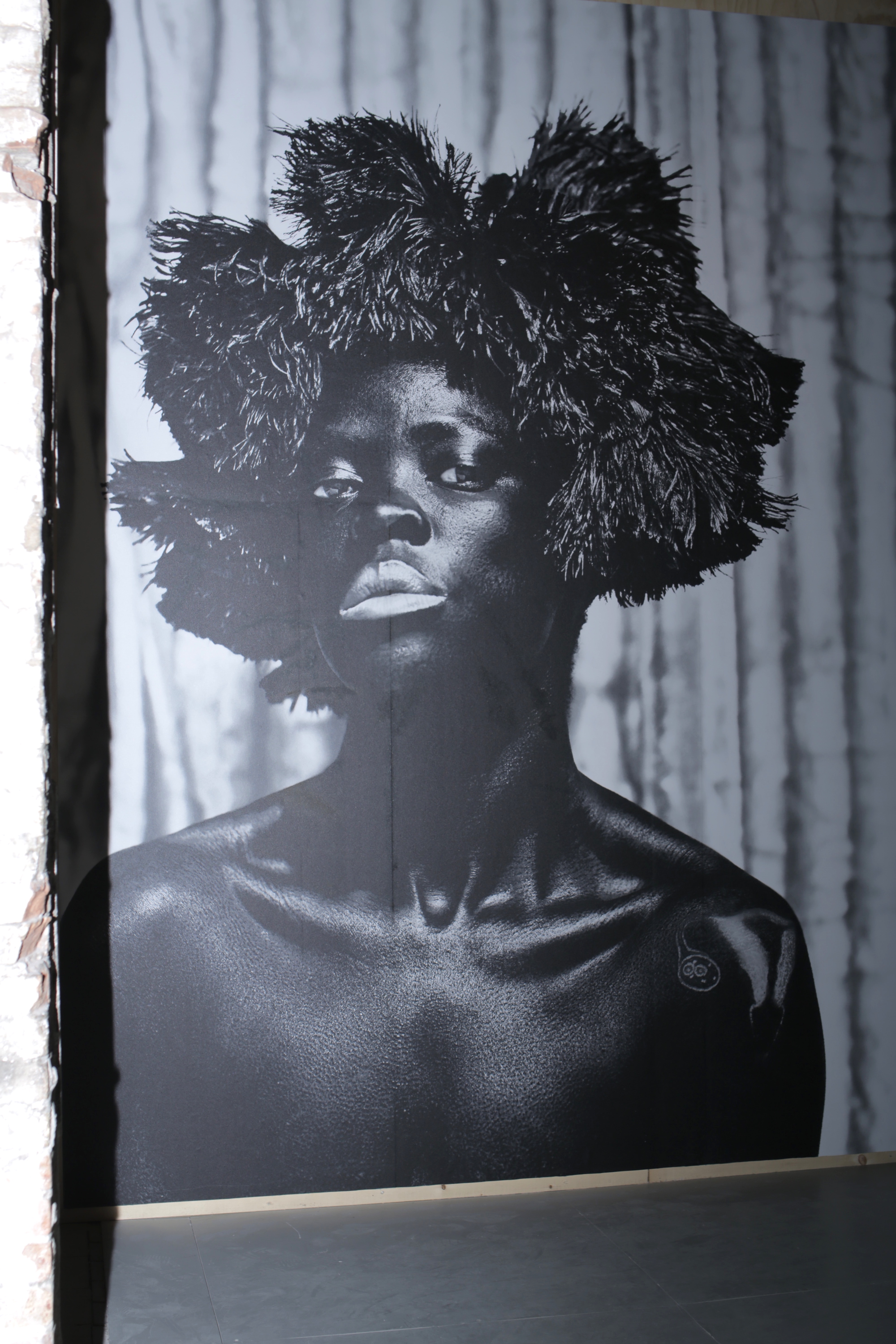

Felicia Abban’s contribution to Ghana Freedom offers lasting visions of black women decked in urbanity. Abban is widely known as the nation’s first female professional photographer and president Nkrumah’s official picture-taker. Her portraits and self-portraits taken between the 1960s and 1970s exhibit African women as statuesque, wide-eyed, smiling towards forced, desired and promised futures. The African women are immortalized in black and white print, illuminating their enduring beauty and grace. It’s a timely resurgence of Abban’s work—the matriarch is often the unsung hero in African familial contexts and the works are the celebration of African women, by African women. The women sit-in-waiting, poised for the future as they veer into the new destiny bought by liberation.

Bopape’s mixed media installation, Lerole: Footnotes (The struggle of memory against forgetting), evokes questions and recurring themes in her work that address land, rights, displacement and ritual. Depicting what appears to be desecrated property, strewn with discarded bricks, slabs of cement, the abandoned expanse resembles a grave-site or voodoo allotment littered with lumps of coal, scattered sands and powders, debris and bricks stacked to resemble the remnants of a ritualistic shrine. Stressing the parallels between physical liberation (made possible by ownership of property), spiritual liberation and resistance to oppressive rule, the work cultivates a future that is realized through survival on the grounds of earth.

Arthur Jafa’s victory with the Golden Lion for best artist in the central exhibition exhibition is an act that has upended institutional systems of cultural erasure. The artist’s work is now a signpost to the road ahead for African and African-diaspora artists who rightfully begin to claim places of increased visibility on the world stage. Having created images, videos and objects from archive material appropriated from online worlds, his body of work surveys the black experience in moments of glory and weariness. Making sculptures from chains, truck tyres, rims and hubcaps, Big Wheel I, Big Wheel II and Big Wheel III draw on the culture of Mississippian monster truck communities. The seven-foot-tall tyres control space and command attention. An enormous wheel hangs from a wooden gallow, resembling the historic punishment of hanging—an act of extermination of black slaves. It also evokes the servitude and indentured labour that marked enslavement and the US automobile industry that followed, offering one of the few routes to survival for many black people, Big Wheel I, I and III force audiences to come into contact with their own racial, social, and economic trappings.

Ka Zenzile’s paintings spark enquiry into how knowledge and language transmits. Examining opposing worldviews and featuring text from idioms and proverbs, the artist’s epic paintings made from cow dung, gesso and oil on canvas playfully taunt the viewer through game-like riddles and verses. The spectator is scorned, empowered or reminded of personal experiences of intimacy through words that slice into emotional terrains.

Kahlil Joseph’s work blurs the lines that separate artistic film experienced within the gallery space and mainstream content that permeates within social media spaces online. Immersing the viewer in a film installation entitled ‘BLKNWS’, the spectator is locked into an uninterrupted assemblage of images simulating fake and recognizable tropes of the black American existence. Raising images of violence, black civic refinement, education, celebrity culture, political heroes such as Martin Luther King and fictitious snippets of actors depicting conventions found in broadcast news, the work examines the debates that black communities are often framed within—wittingly or unwittingly—throughout mass media.

Otobong Nkanga’s 25.9 metre-long installation Veins Aligned awarded her a Special Mention at the Biennale. Often presenting distance, land and space as a body, the Nigerian-born and Belgium-based artist’s work formed a flesh-coloured glass and marble snake-like sculpture, which senses its way through the Arsenale. At times resembling the human body and its ties to natural resources that in circulation, create lines of profit, the work examines earthly exploitations—a seemingly unending process.