The Dada movement was born 100 years ago as an absurdist reaction to the atrocities of the First World War, the art establishment’s capitalist structure and bourgeois interest in art as a form of empty aestheticism. Since then society has hurtled along a timeline of further atrocities, revolutions and counter revolutions. However, the seemingly irrational joy of the Dada method has never been far behind as a slap around the face, a tickling ambush, a shock. Dada manifests itself today in some familiar forms: collage and readymades, methods invented and championed by the Dadaists, are still prevalent, .

The French-German Dadaist and pioneer of abstract sculpture, Jean Arp, said that Dada aimed to “destroy the reasonable deceptions of man and recover the natural and unreasonable order.” There are plenty of 2020isms that need destroying: division, paranoia and conspiracy theories, to name a few. So when we find no reason on Twitter or no joy in the news we should turn towards the restorative power of chaos—if only a version seen through the wide eyes of today’s artists.

The irreverent spirit of the movement is visible today in how it informs artists’ processes; the idea of absurdity as a tool to help to explore personal identity, and as a way of creating something different and surprising in a visual culture bombarding us with stimulus. I spoke to four practitioners who continue to uphold the irrational art-making tradition of Dada.

- Sang Woo Kim, Public Toilet, 2019

Sang Woo Kim

Sang Woo Kim is a multidisciplinary artist who moves between sensitively surreal painting and bold, conceptual installations. For Kim, absurdity becomes a gateway to a personal countercultural universe. “Creating my own world and trying to speak my own language could be seen as absurdity,” he says. “Irrationality in the context of art shows a different, perhaps unseen perspective, and gives an opportunity to view or think in a different capacity.” His 2019 exhibition in Venice, Public Toilet, made direct use of Dada titan Marcel Duchamp’s 1920 Fountain while questioning the role of the traditional gallery space as a whole.

He rejects the flippant definition of the absurd as baseless or unfounded, and thinks of it as a chance to educate audiences on the motivations behind the art. “The reason and concept behind these pieces are far more thought-out than they first appear, as they could be deemed as ‘pranks’ or ‘traps’,” says Kim. “The thought process of the toilet becoming a sculpture, or a public toilet becoming an installation, is far more beautiful than a sculpture or installation conceived as such.”

Leo Fitzmaurice

British artist Leo Fitzmaurice handles seemingly irrational ideas with a joyful wit and a graphic eye. Works such as Arcadia and Misconstruct offer a bewildering sense of place through agile re-imaginings of familiar objects. There appears to be a serious motivation behind the playfulness of Fitzmaurice’s work: “As a society we confuse information with the thing that it refers to, which is a big mistake; information being light and compliant and reproducible; life being heavy and slippery and unique,” he says. “Moreover, I believe we are suffering from a proliferation of this information, and within our ever-increasing multidimensional webs of information I see us more as flies than spiders. For me, anything that can break through this ‘info-lusion’ can be potentially useful.”

Matilda Moors

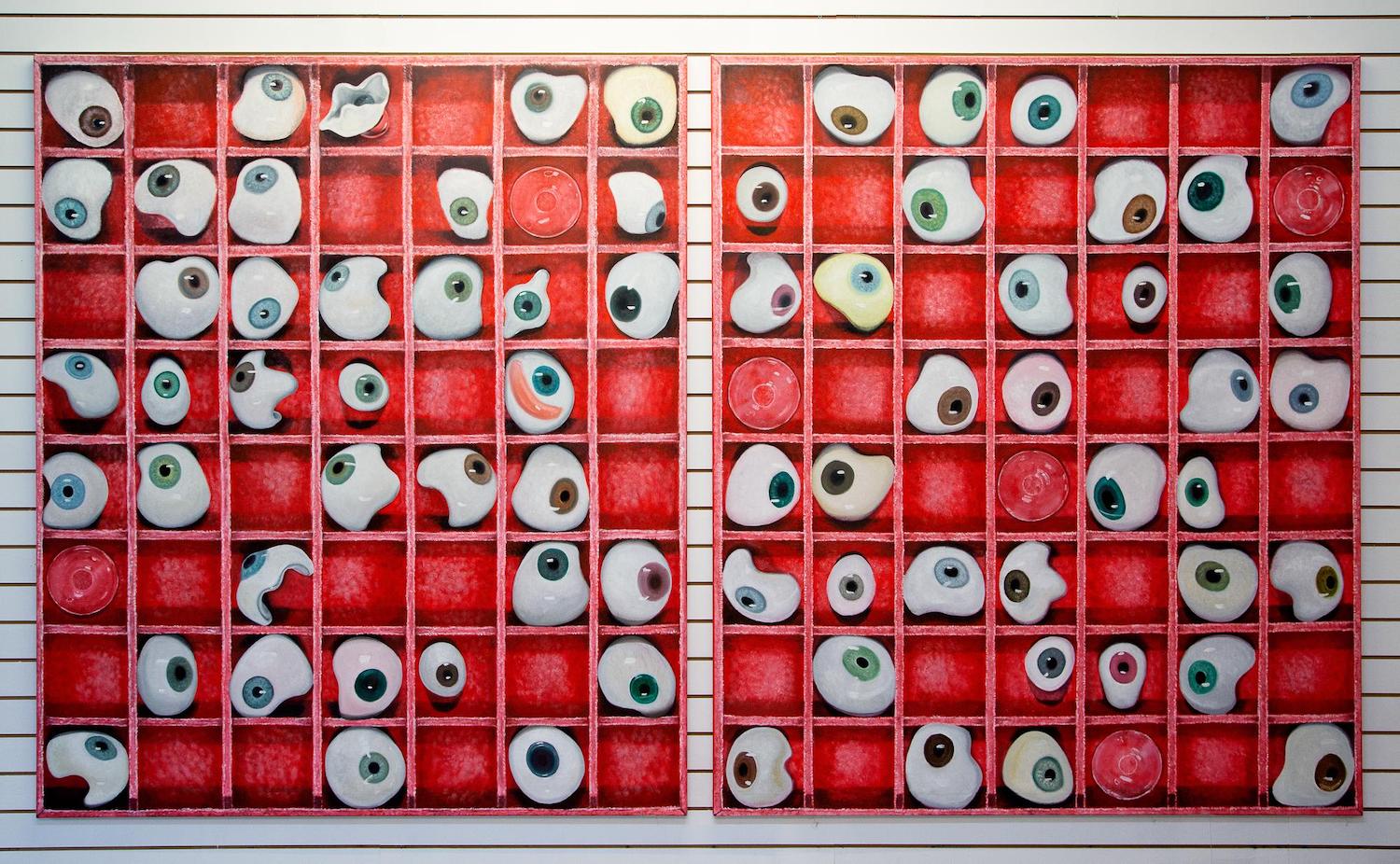

Matilda Moors’ work has teeth—quite literally, in the case of her piece A Tasteless Offering. Her arresting installation projects are proudly absurd, but there’s a sense of humanity to much of her work, such as the puddles of latex vomit that form her piece titled Projections. “It’s a remake of fake vomit so it’s quite literally a joke,” she says. “One that has fallen flat, in the sense of its dimensions as well as its inability to actually make you laugh out loud.”

Moors’ invocation of the cartoon aesthetic calls to mind the Dadaists’ appropriation of commercial images of the time, such as Raoul Hausmann’s The Art Critic, which used advertising imagery to poke fun at the “capitalist forces” at work in the commercial art world of the time. By using the chaotic energy of cartoons, Moors aims to intensify the relatable human experience. “The kind of duress a cartoon body is put under—how many beatings Wylie Coyote and Tom have to take—acts as a metaphor for how far you can push someone and have them reshape themselves and try again,” she says.

For Moors, it is necessary to strike a balance when wielding these spirited ideas. As with Sang Woo Kim’s work, mischief becomes a delivery system for something more meaningful: “There is a softness to mischief, it’s not overtly destructive.”

Ted Targett

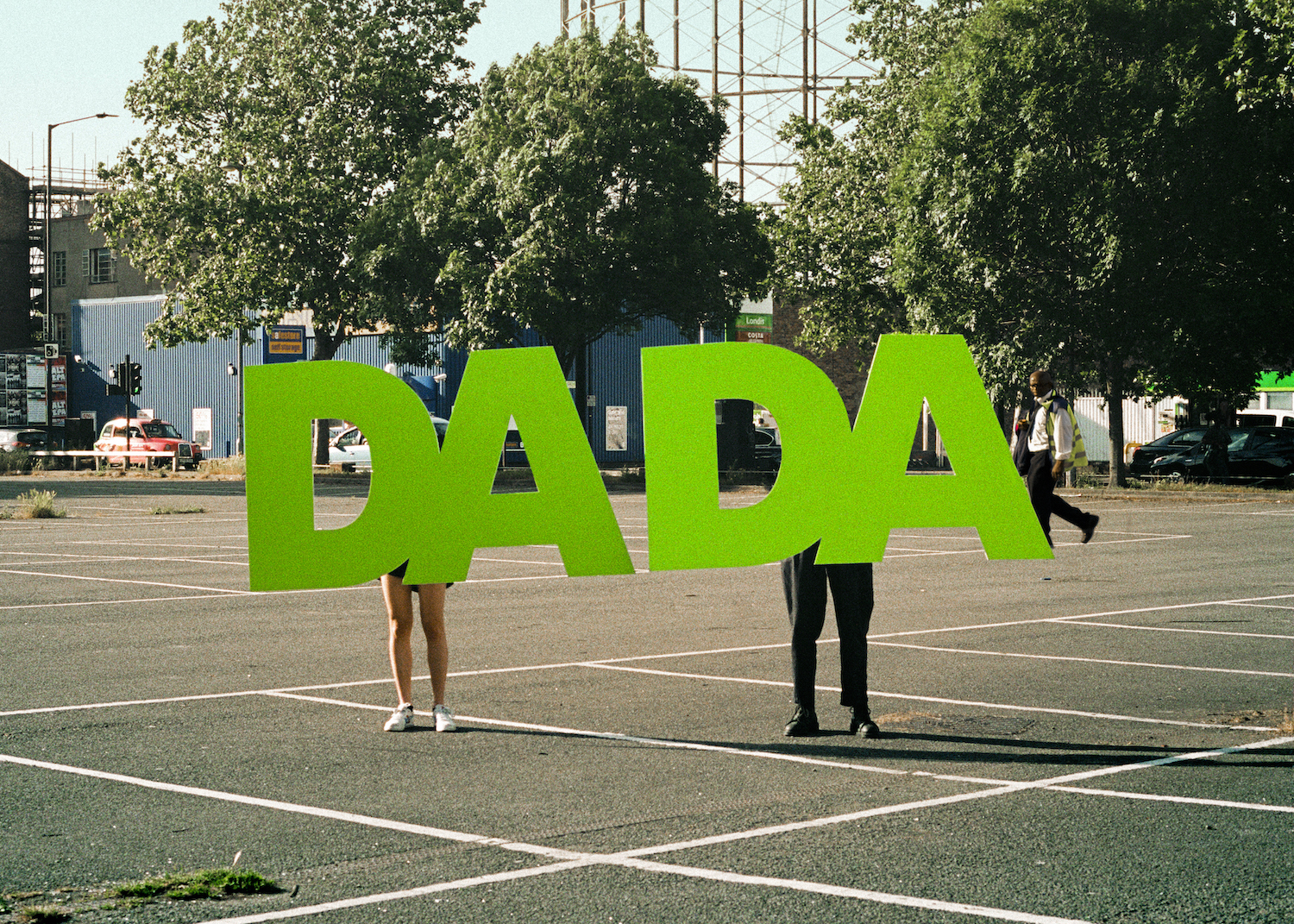

Ted Targett is a curator at the Royal College of Art and director of design studio Numbered Editions. I was interested to find out what he thought of the role of the gallery and the established art world systems when handling the absurd. “Think about authenticity,” he says. “Realistically, does absurdist art really work within an ethereal white box? Most likely not. I say scrap the gallery and do it in public. You’ll get better results there—mainly because in galleries, after crossing the threshold your behaviours and etiquette change.”

With this in mind, Targett’s Numbered Editions team found themselves in an Asda supermarket car park recreating Tim Mancusi and Bill Gaglioni’s 1975 work Dada Land, for which they “held up” the Dada tradition by carrying a pink cutout of the word ‘DADA’ beside a motorway. “It’s like telling a really obvious dad joke. It was a way of us escaping absurdity traversed through the art world and into the public where things are less fixed or strict.”