In 1991 the Internet was not the gargantuan world of images it is now; it was ruled by words. That year, Tim Berners-Lee brought the world wide web into existence with the first web page: an austere thing featuring black text and blue hyperlinks on a white background, whose sole purpose was to explain exactly what this new online world was. As computer screens were only just beginning to light up the living rooms of those who could afford them, it was probably a good place to start.

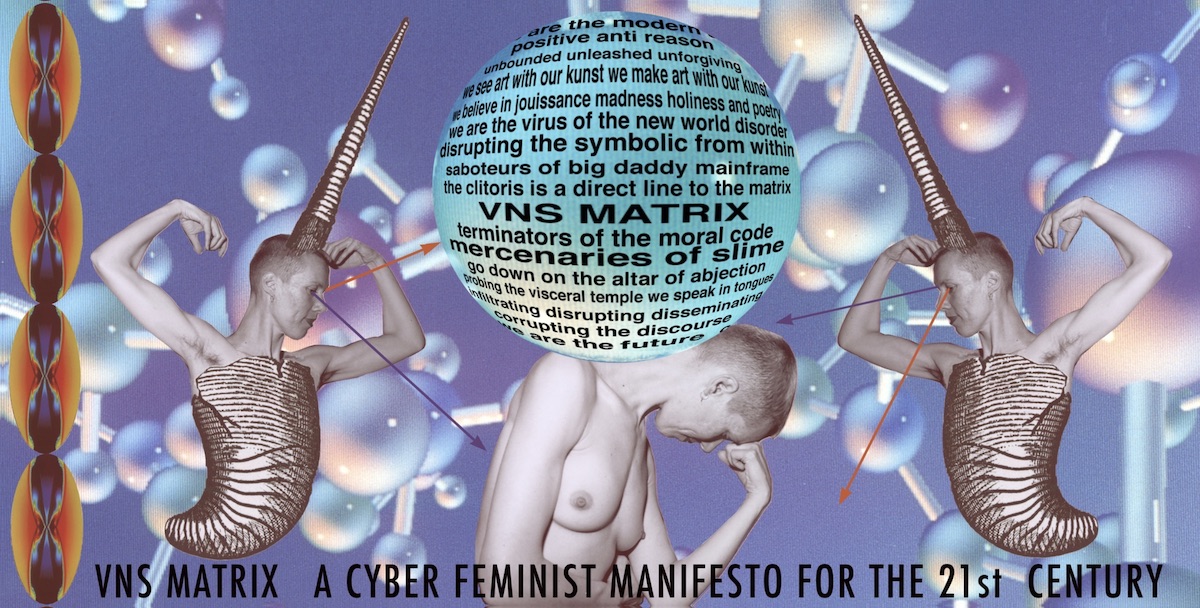

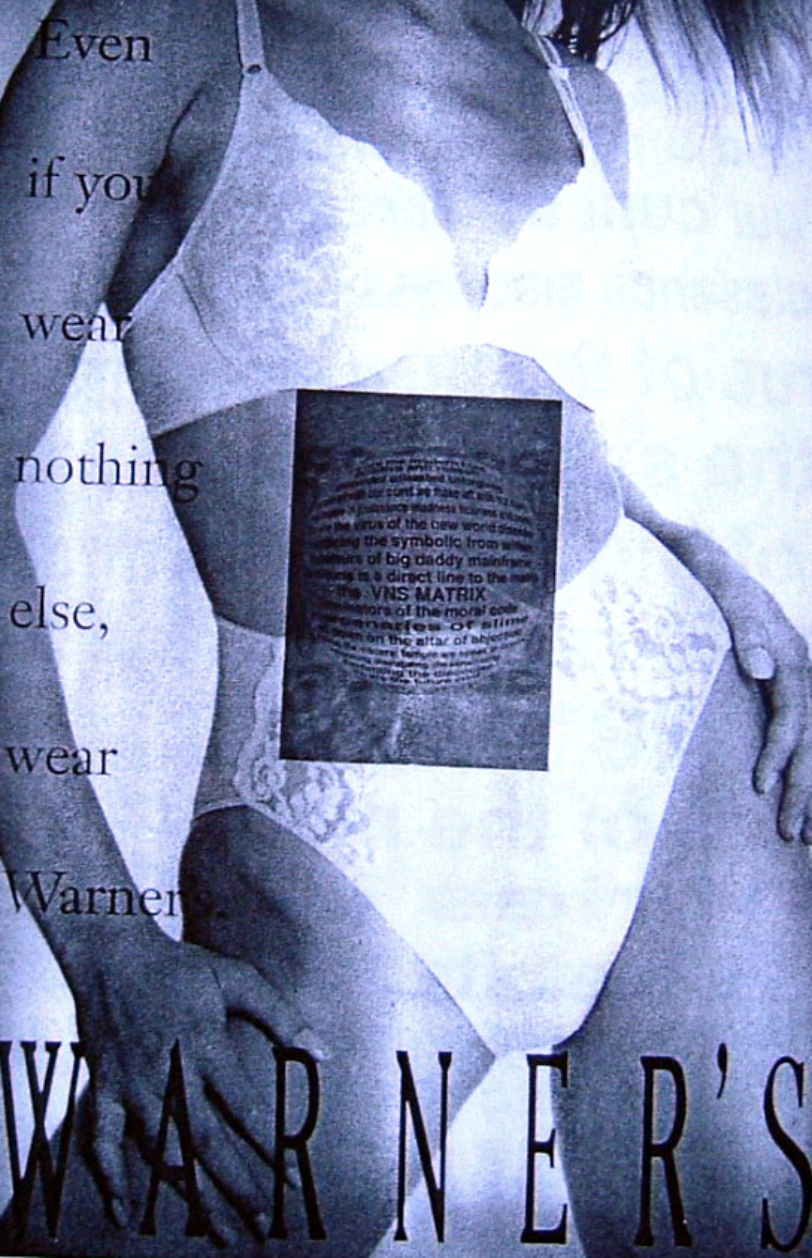

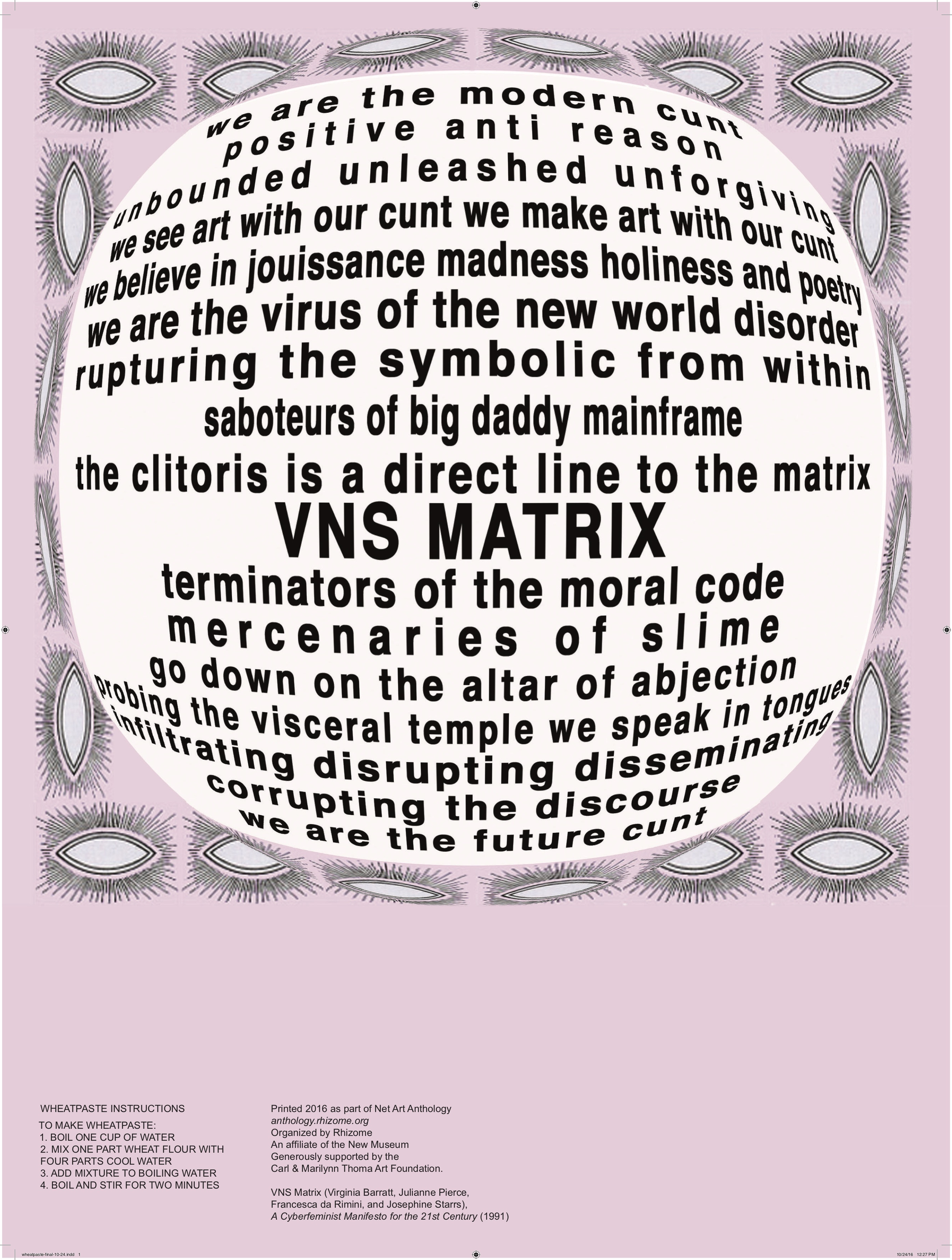

But there was something less savoury bubbling under the glassy, curved surface of those screens. In the Southern Australian city of Adelaide, artists Josephine Starrs and Julianne Pierce joined forces with Francesca Di Rimini and Virginia Barratt and pooled their rage at an overwhelmingly male tech world—one that assumed maleness as the default. Together they created A Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century—first available on early Internet forum LambdaMOO and in the form of wheat pasted posters that appeared around Australian cities, beamed across the country via fax and post. It was printed in magazines in many different languages, and in 1992 the collective made a huge billboard featuring the text in a collage fizzing with Dadaist energy, a reproduction of which is currently on show in London at the ICA’s exhibition I, I, I, I, I, I, I, Kathy Acker

.

“The clitoris is a direct line to the matrix,” announces the manifesto—a hyperbolic play on words that connects the Internet to the womb (the Latin translation of “matrix”) and unleashes a bodily sexuality onto the male “technophiles” who “jack into the machine and want to forget about the body“.

The manifesto had such impact not because of any suggestion of action, but because, with all its outrageous language, it is a charged and playful assertion of women’s existence/place/anger/power in the early days of the Internet. It snatches you by your shirt collar and spits its anarchic poetry right between your eyes. It seems as if the words have been brewing somewhere deep down for millennia, finally seizing a moment of cybercultural freedom and rushing out from the screen like a geyser from a hot spring. The group do not hesitate to offer their own plethora of genesis stories, the “most consistent” being that they “crawled out of the cyberswamp in the particularly hot summer of 1991

and via an aesthetics of slime initially generated as porn (by women for women) VNS Matrix forged an unholy alliance with technology and its machines”.

“Like all memes, the manifesto’s power lies in its having given rise to swarms of iterations, spin-offs and, importantly, critiques”

In the same year, Donna Haraway published her similarly explosive A Cyborg Manifesto. A “myth” about the current and future fusion of humans, animals and machines “about transgressed boundaries, potent fusions, and dangerous possibilities which progressive people might explore as one part of needed political work”. Though Haraway did not describe herself as a cyberfeminist, she and VNS Matrix, along with theorist Sadie Plant, who simultaneously coined the term whilst operating on the other side of the world at Warwick University, opened up a conversation about the political possibilities of the Internet when in the hands of those most ignored and oppressed in the physical world.

A Cyberfeminist Manifesto for the 21st Century, Courtesy VNS Matrix

Like all memes, the manifesto’s power largely lies in its having given rise to swarms of iterations, spin-offs and, importantly, critiques. Melinda Rackham points out in her essay A Manifesto that it (and 1990s cyberfeminisms in general), particularly in their focus on biology, were often exclusionary, failing to recognize trans and non-binary experiences and the importance of intersectionality.

The Internet is now a very different place from the world of The Cyberfeminist Manifesto and can often feel like one with far fewer possibilities than promised; wading through targeted ads whilst doing your upmost to not fall into another YouTube hole may not make you feel quite like “the virus of the new world order”. But the world wide web is constantly morphing, and proliferations of artists and writers such as Martine Syms, Aria Dean, Molly Soda, Sondra Perry

and Amalia Ulman continue to examine and rethink the ever-shifting realities of being a woman online.