At first glance, you’d be forgiven for laughing upon entering the first room of Stefanie Moshammer’s Each Poison, A Pillow. Three phones play three videos, which we watch through a mirror. The videos show a collage of videos of women — all drunk — falling, fighting, pissing, and crying, all of which Moshammer collated by searching the hashtags #drunkgirls and #drunkwomen on social media. We might initially titter at the slapstick, childlike nature of the clips, but the longer we look, seeing both the video and ourselves reflected in the mirror, the darker they begin to feel. This balancing act between humour and horror is something Moshammer deftly weaves into the work, straddling a dialectic between lightness and darkness. Attracting us, in her words, “through a certain beauty”, but as we begin to lean in, cruelty is revealed: “In the beauty always lies the devil.”

Screenshots of these videos are recreated on canvas, using ink-print and acrylic paste and are also printed onto a cascading fabric, reframing the videos with a romantic glow, reflective of the way alcohol(ism) is “so much romanticised or normalised” in society, sewn into the fabric of our culture; posted and reposted on our social media to reframe and project that we too are having a great time, just like everybody else. Before leaving the room, we catch a glimpse of ourselves once more in the mirror, forced to confront ourselves reflected in the work.

While the first room is the only one with a physical mirror, it could be said each room offers a different form of reflection. In Each Poison, A Pillow, the Austrian artist explores the subject of female alcoholism not just in society but through her relationship with her mother, whose own struggles with alcohol form the foundation and thread of the work. Their own personal dynamic and collaboration offer an intimate and evocative insight into the complexity of addiction and those affected by it.

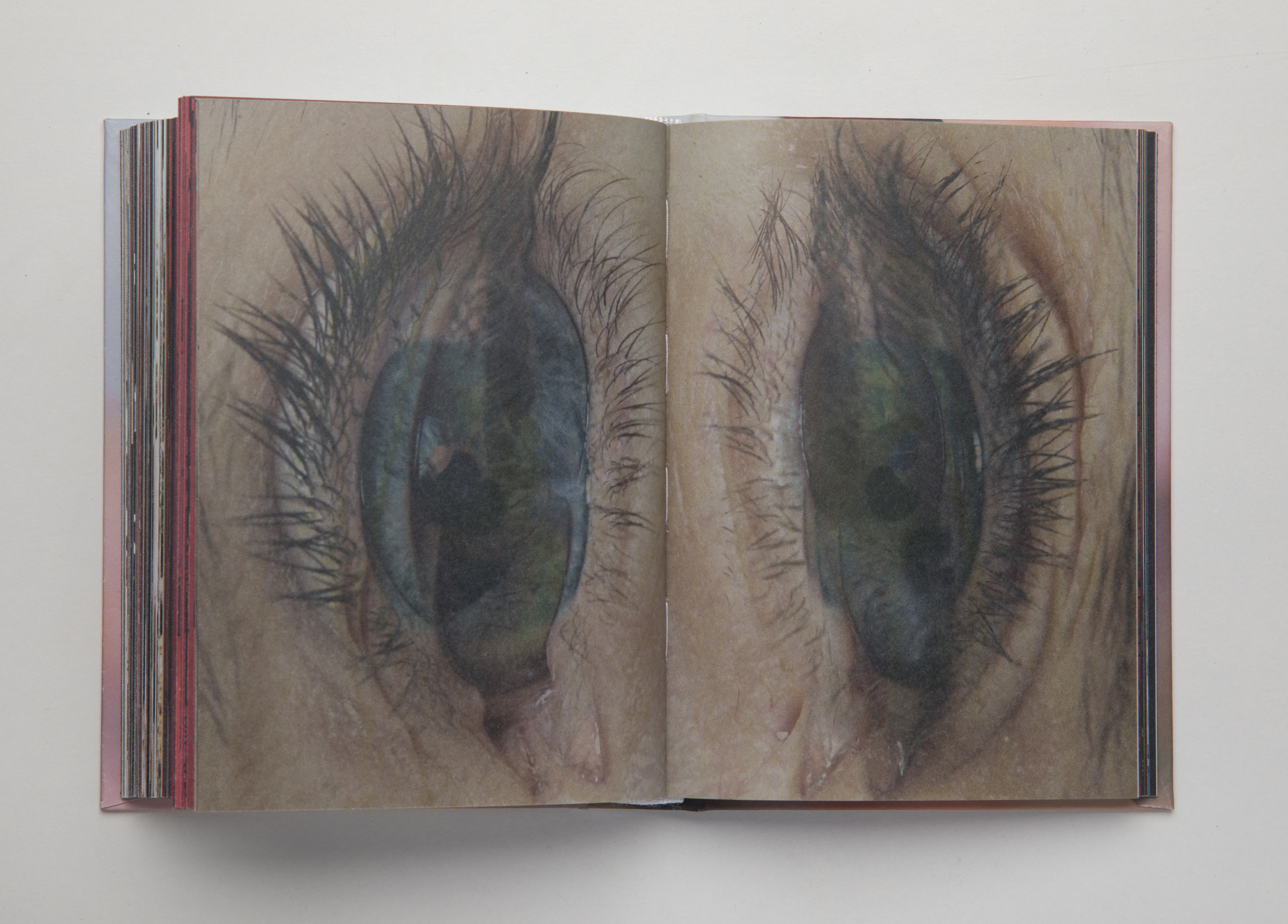

In the second room, two monitors, each displaying an eye of Stefanie and her mother, face each other. The video loops as the eyes flit through various emotions – complex and contrasting – and attempt to mirror or decipher the emotions of the other. Parent and child reach for understanding; “I tried to put myself into her position,” as Moshammer puts it. Here, the artist articulates the dichotomous nature of a relationship with an alcoholic parent, one where “the positions change” and daughter can become mother, breathing empathy into the space between the monitors. There is, however, still a lingering anxiety, a search for an origin in her mother’s eye, and an attempt to answer the question, “Could I find myself in the same situation? Is there a risk of me becoming an alcoholic as well?” In both the work, and her accompanying book, Each Poison, A Pillow, the images of the eyes are reflected, become distorted, and eventually become overlaid. A possible answer to the question or simply the gap closed, comprehension achieved?

In the same room, we find ‘Slow Growing, 2023’, a large stone inside a glass bottle, a reference to the letter Moshammer’s mother wrote in the book in which she describes the transformation of alcohol from a soft pillow to a hard stone. It was important for Moshammer that her mother offers not just a thematic backdrop but “that she could be present” in the pieces themselves, not only those that she features in but also in her physical and spiritual contributions.

The work titled ‘Nowadays, 2022’ captures my attention in this regard, an image of an apple: multiple pieces of peel reattached to the fruit in an almost patchwork blanket of its own skin. At first uncanny or perhaps unsettling, in the context of the show, it mirrors the process of recovery and intimately and evocatively reveals the deconstruction and reconstructing at play in the act of a constant renewal of self. For Moshammer, “it comes from inner pain” and the ways in which you can “reconstruct it in a new, maybe almost positive way”. It has a naive, childlike quality to it but ultimately reveals the intrinsic bravery at the heart of healing and the collaborative process Moshammer and her mother undertook in the making of this exhibition. The simple vulnerability of a peeled apple imperfectly put back together.

A letter found at her parents’ house three years ago sparked the idea for the show. In the letter, an eight-year-old Moshammer asks, “Can you make my wish come true that my Mommy never, never, never will be drunk again.” The letter finds its mirror in the show —both figurative and literal — with a wall of cocktail glasses filled with colourful liquids — something innocent and playful, contained within an adult vessel. Much like the letter, that childlike optimism casts a sanguine glow on the very adult nature of addiction. It would be easy to see the work as a form of therapy or redemption for the young Moshammer who wrote the letter, but Moshammer insists this doesn’t come from a place of trauma. “It wasn’t like that […]I don’t feel like it’s a healing work for me”. Instead, Moshammer’s considered distance from the emotion of the work offers a chance “to open up a discussion about a topic that hasn’t really been talked about a lot.” Her own experiences are an offering — an invitation to others to be open, vulnerable, and receptive to a taboo topic.

The collapsed dialectic of child and adult, beauty and the devil, strength and weakness, finds itself most aptly delineated in the exhibition’s title, Each Poison, A Pillow. A phrase etched in the back of a sketchbook that the artist, still unsure why she initially wrote it down, elaborates as “drugs and love as one big pillow […] the pillow something so soft and comforting but also domestic”. A gesture to the covert struggle of female alcoholism that Moshammer points out “takes place in the domestic space”. A collection of pillows in room three displays family images of Moshammer’s mother with a drink in her hand, a search through the archives to trace a possible origin, the signs you might have missed, but also an empathetic acknowledgement of the seductive comfort of the poison, dressed up as the supportive embrace of a pile of soft pillows.

The temptation of embrace is soon interrupted, however, by the crashing of bottles that comes from Moshammer’s 4-channel video installation, ‘Mother, Task I-IV, 2022’. Here, we see her mother depicted in various positions balancing glass bottles: “They’re almost a bit like yoga positions […]positions to make your body feel better.” A contrast then with the shocking sound of the glasses breaking. This is a collaborative work between the two of them as they attempt to understand her mother’s “battle with alcoholism and its impact on me as her daughter.” The video plays on a loop, the continuous cycle of ups and downs of her addiction, dancing between composure and falling apart. Just when she seems to have her balance, a bottle falls, breaking the silence, much like the disruption and tension of being in a room with people under the influence, like the #drunkgirl videos from the first room that oscillates between comedy and darkness. For Moshammer, “it shows me her strengths, but also, at the same time, this weakness that she has” and perhaps not just her mother; maybe “that’s just part of us humans in general”, a balancing act of strength and weakness.

“This whole work doesn’t really have a beginning and an end,” says Moshammer; “it’s like pieces of a puzzle”. Instead, the exhibition unfolds sporadically and organically through an array of mediums, each offering an unfiltered look at the subject and reflecting the nonlinear nature of recovery. “People always ask me if she’s still having an alcoholic problem.” And the answer? “Yeah, she is. An addiction keeps on a lifetime, even if you are fine at the moment.” Moshammer’s research with her mother’s therapist offer insight into the often decade-long journey from acknowledging a problem to seeking recovery and emphasises the slow and insidious nature of alcohol addiction. She points out how alcoholism doesn’t look or behave like other illnesses; “it has so much of an effect on the physical but also emotional body, emotional demand”. Like the addiction itself, alcohol haunts the rooms as an ever-present spectre, offering up more questions than answers at times. A mirror of her mother’s letter in the book in which she admits, “I’m still looking for answers to all these questions”.

This fragmented approach could, at times, seem isolating, but Moshammer is keen not to push a feeling onto the viewer. “It always depends on your own story and how you read a work or what you want to take from it”. In this sense, she successfully intertwines a personal narrative with broader societal reflections. While empathy is sewn into the fabric of the work, Moshammer never relies on sentiment to evoke a certain feeling. By “not giving too much of an explicit direction,” she depicts the multifaceted nature of the subject matter, deftly avoiding a one-sided narrative. She challenges viewers to rethink and reflect (quite literally) on their perceptions of alcohol and initiates conversation, revelling in the space between joy and darkness without casting judgment. Moshammer probes, alludes to and questions the complexity of reconstructing memory and alcohol addiction but never imposes an answer. In reality, families are complicated, memory is dubious, and addiction is contingent. In Each Poison, A Pillow, the subject is allowed to just be, in Moshammer’s words: “It exists, and there is no clear answer to it.”

Words by Lucy Carless